Take a photo of a barcode or cover

I have been a fan of Karl Ove Knausgaard for as long as I can remember, and this series has been absolutely wonderful, so I was expecting a fine and fitting conclusion. Unfortunately, this let the entire series down. No-one is more sorry about that than me. Don't get me wrong, I was bound to be disappointed at some point given my super-high expectations, but I never imagined it would be by Knausgaard.

The main issue is simply that the book is too long. It could've worked like a charm had an editor have cut it down by quite a substantial amount of pages, so it dragged on and on and felt as though we literally weren't moving anywhere. The middle section of the book was the worst part and so disastrous that I almost gave up on reading it in order to substitute it for something more enjoyable. A decent editor could've really made this taut and tight and tuned it up properly. The narrative at times was so difficult to get through as it felt like wading through treacle - at a complete standstill. Each time this happened there was a loss of momentum and for a reader attempting to appreciate the story, this was extremely hard work, not to mention tedious. The structure only added to the problem - many overlong sentences naturally made it hard work.

Overall, this is not a book I would recommend, that makes me incredibly sad to say that as the author's works are usually reliably engaging, excellent and masterpieces. However, I would pass on this one and spend your time on something with more finesse.

The main issue is simply that the book is too long. It could've worked like a charm had an editor have cut it down by quite a substantial amount of pages, so it dragged on and on and felt as though we literally weren't moving anywhere. The middle section of the book was the worst part and so disastrous that I almost gave up on reading it in order to substitute it for something more enjoyable. A decent editor could've really made this taut and tight and tuned it up properly. The narrative at times was so difficult to get through as it felt like wading through treacle - at a complete standstill. Each time this happened there was a loss of momentum and for a reader attempting to appreciate the story, this was extremely hard work, not to mention tedious. The structure only added to the problem - many overlong sentences naturally made it hard work.

Overall, this is not a book I would recommend, that makes me incredibly sad to say that as the author's works are usually reliably engaging, excellent and masterpieces. However, I would pass on this one and spend your time on something with more finesse.

I am so happy about Linda, and I am so happy about our children. I will never forgive myself for what I have exposed them to, but I did it and I will have to live with it. Now it is 07.07, and the novel is finally finished. In two hours Linda will be coming here, I will hug her and tell her I have finished, and I will never do anything like this to her and our children again.

Malmö, Glemmingebro, 27 February 2008–2 September 2011

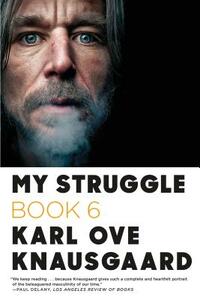

7 years later, it's 13.45 on 5th September 2018, and I would have to admit to a similar, albeit slight, sense of relief after finally reaching the end of the 3,966 page epic that is My Struggle, this final volume alone clocking in at 1,168 pages.

But that said, Min Kamp is one of the most important literary works of the 21st Century to date. The only book of comparable length I have read is Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu, which clocks in at 4,200 pages in the Moncrieff/Kilmartin/Enright translation, and the comparison is a fitting one.

It's also been a long wait for the English translation - Knausgård took only 3.5 years to write the entire series, but we've waited 7 years for the English version of book 6. His usual translator, Don Bartlett has assistance here from Martin Aitken, who translated the first half of this volume: the most notable style difference being that Aitken incorporates a number of Swedish / Norwegian words, in part reflecting I think the original where Knausgård slips between the two languages when addressing his children, but is does still seem distinctive versus the earlier works and the other half of this volume:

‘Också kram!’ said John. Me cuddle too.

or:

Plastic nets full of mussels lying on their bed of crushed ice. ‘Blåskjell. Mussels,’ I said. ‘What?’ she said. ‘Musslor,’ I said. ‘Blåmusslor.’

Book 6 brings the story of Knausgård's life up to date. It begins the day before the first of the books is to be published, and with two other books nearly complete, and, looking back to the start of the project, it spans the time up until the writing and completion of the book we are reading.

This makes for a more stimulating read than some of the earlier books. In those books Knausgård was adept at writing as he would have experienced and viewed the world at the time he was describing, without any ironic distance: book 4 he regards. looking back, as a success precisely because it is full of the terrible banality and vigour of youth, it is a comedy of immaturity, but that didn't make for a very stimulating read (my review https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1287483953). Here, the writer and the character are one and the same, a 40-something world-class novelist and literary theorist, and the book has much more intellectual heft.

The first volume was written in a black period for Knausgård , a cathartic work and a very introspective one:

Why had I written such things? I had been so despairing. It was as if I had been shut away inside myself, alone with my frustration, a dark and monstrous demon, which at some point had grown enormous, and as if there was no way out. Ever-decreasing circles. Greater and greater darkness. Not the existential kind of darkness that was all about life and death, overarching happiness or overarching grief, but the smaller kind, the shadow on the soul, the ordinary man’s private little hell, so inconsequential as to barely deserve mention, while at the same time engulfing everything.

But as this novel opens, he is confronting the reality that he has written a book, one that while a novel is a novel-without-fiction (as Javier Cercas would term it), about real people, some very close to him:

Four hundred and fifty pages, a story about my life centred around two events, the first being my mother and father splitting up, the second being my father’s death. The first three days after he was found. Names, places, events were all authentic. It wasn’t until I was about to send the manuscript to the people mentioned in it that I began to understand the consequences of what I had done.

And the reaction is worse than he had feared. His uncle Gunnar, his father's brother, who plays a key role in the first book, is particular incensed:

I spent half an hour talking to Geir Angell on the phone, ate a packet of cold fishcakes for lunch, made a fresh pot of coffee, and then when I came back in from the balcony there was an email from Gunnar.

The subject line said ‘Verbal rape’.

Gunnar aggressively challenges many of the facts in the book, not just his interpretation, and threatens to take legal action, obliging his publishers to instruct solicitors and to consider whether names need to be changed, passages omitted, the story even changed. At one point, Knausgård wonders if perhaps, as Gunnar suggests, the work is fictional, but:

If I accepted that perspective I would be obliterating myself. Not once had I considered myself to be exaggerating when writing about what had gone on in the house, not once had I considered myself to be exploiting dad and grandma, the events I was describing were too overwhelming for that, and what I was delving into was too important.

Although he does accept that he may have been harsh on his father, something he ultimately deals with by the (odd) approach of removing his father's name from the book:

I’d read a short novel by Peter Handke called A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, it was about his mother’s suicide and thereby autobiographical. In contrast to my own prose, which constantly leaned towards the emotional and evocative, Handke’s prose was dry and unsentimental. When I started writing I’d been trying to achieve a similar style, if not dry, then raw, in the sense of unrefined, direct, without metaphors or other linguistic decoration.

...

[But] I had written [...] in a way that was almost diametrically opposed to Handke’s, reaching continually towards affect, feeling, the sentimental in contrast to the rational, and dramatising my father, allowing him to be a character in a story, representing him in the same way as fictional characters are represented, by concealing the ‘as if’ on which all literature depends, and thereby traducing him and his integrity in the most basic of ways, by saying that this was him. I had said the same thing about all the novel’s characters, but only in the case of my father had I done so in a way that failed to show consideration to him and the person he was.

The first third of Part 6 (c450 pages, i.e. a long novel in itself) covers very little elapsed time, as Knausgård and his publishers work on how to present the novels, as well as dealing with the legal and reputation issues arising.

‘We put it out as a series of twelve. A book a month for a year. We could set up some kind of deal so people can subscribe and get the whole lot. What do you reckon?’ ‘It’s a fantastic idea!’ I said.

...

When he [called] it was to tell me they couldn’t make it work with twelve separate publications, there were too many practical problems and the figures wouldn’t add up. He suggested six instead. Three in the autumn, three the following spring.

Six books that weren’t independent of each other, that didn’t seem good to me. I needed to divide them differently so that each became a stand-alone book in its own right, which was to say I had to end up with six novels that could also be read as a single, continuous narrative. Doing it that way, the first book came to four hundred pages, the second to five hundred and fifty, and the third to three hundred. After that I ran out of material. If I was going to do it that way, I would have to write three new books in ten months. Which wasn’t implausible, I’d been doing about ten pages a day for the last six months as it was, in the region of fifty pages a week given the fact that I wasn’t allowed to work weekends.

That last 'wasn't allowed' is very telling - referring to an agreement with his wife that weekends are family time. He admits later in the book that his desire is to eliminate as much complexity as possible from his life - and family life is of course chaotic:

Why do I organise my life like this? What do I want with this neutrality? Obviously it is to eliminate as much resistance as possible, to make the days slip past as easily and unobtrusively as possible. But why? Isn’t that synonymous with wanting to live as little as possible? With telling life to leave me in peace so that I can … yes, well, what? Read? Oh, but come on, what do I read about, if not life? Write? Same thing. I read and write about life. The only thing I don’t want life for is to live it.

Interspersed with the publishing shenanigans are the signature Knausgård descriptions of life, here focused on the day-to-day details of living with three young children. For example, in the following paragraph that describes the next novel he was contemplating, one called (with anotherr obvious nod to Nazi Germany) The Third Realm:

‘The body, the blood’, ‘biology’, ‘the atom bomb’. And Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things had been appearing in my notes ever since the mid-90s. But it was a novel. It was. A world described through the material and the mechanical, sand, stone, shells, atoms, planets. No psychology, no feelings. A story that was different from ours, though similar. It was to be a dystopia, a novel about the final days, told by a man alone in a house, in the midst of a dry, warm landscape in late summer. And I had an ending ready, I had told it to Linda, who had lit up, it was sublime, amazing. It was!

‘OK, do you want your baths now?’ I said, returning the book to the shelf. The girls slid down from their chairs and skipped off to the bathroom. ‘Yes!’ cried John, and toddled after them.

He provides an eloquent justification for his minutely detailed approach in the novel:

A novel that was meant to say something true about reality could not be made too simple, it had to contain an element of exclusiveness in its communication, something not common to or shared by all, in other words something of its own, and there, at some point between the madman’s own particular and therefore uncommunicated ramblings, meaningless to everyone but the madman himself, who found them fascinatingly relevant, and the genre novel’s fixed formulations and clichés, which had become clichés by being familiar to everyone, was the domain of literature.

...

This was perhaps the greatest difficulty in writing autobiographically, finding out how material was relevant. In real life, of course, everything was relevant and in principle equal, since it was all there in existence at the same time – the great oil tankers at anchor in the Galtesund in the 70s, the plum tree outside my window, mum’s job at Kokkeplassen, dad’s face when he drove by in the car and I was out somewhere and saw him, the pond where we skated in winter, the smells inside the neighbours’ house, Dag Lothar’s mum that time she made milkshakes for us, the strange car that was parked one night down at Ubekilen, all the fish we had for dinner, the way the pine trees in next door’s garden swayed back and forth in the strong autumn winds, dad’s rage if I happened to dig my knee into the back of his seat in the car, the waffles we made every Tuesday, my great infatuation with Anne Lisbeth, the footballs mum and dad brought back for us from a trip to Germany, mine green with red hexagons, Yngve’s yellow with red hexagons, the way we stood one day and kicked them as high into the air as we could to see if they could reach the military helicopter that happened to come sweeping low over the playground.

But equally telling is a comment from his best friend:

‘You don’t have to say everything that comes into your mind, you know. Kids do that. Adults can put their utterances through quality control first.’

And my favourite example of oversharing - he tells us his PIN number and why he chose it.

So on to the middle section of the volume - perhaps the most infamous in the whole novel - the long essay on Hitler's Mein Kampf. The justification he gives for this is both the common name (although presumably this was not a coincidence?) but also his finding a Nazi pin in his late father's belongings then later a copy of Mein Kampf in his father's mother's.

Because the first book of this novel shares its name, My Struggle, with Hitler’s book, and because Hitler’s book and the Nazi pin were unexplained mysteries in that story, or perhaps not mysteries, but more exactly fields of the past that manifested themselves in the present and which I felt unable to trace back to anything I knew in that past, I had decided to write a few pages about Hitler’s book.

Although Knausgård is of course incapable of writing 'a few pages' and instead we get:

Four hundred pages about pre-war Vienna, Weimar between the wars, how times and psychology, art and politics are closely linked, and the formula for all things human, I-you-we-they-it.

This is primarily a highly literary treatment, one that for example opens not with Hitler at all, but with a 60 page detailed deconstruction of a poem by Celan.

So much of dad was collected in his name. He spelt it differently when he was young, and changed it sometime in his forties, and as he lay there dead and nameless, the name the mason chiselled into his headstone was spelt incorrectly. The stone is still there, in the cemetery in Kristiansand, with its misspelt name, on top of the interred urn containing the ashes of his body. And when, ten years later, I began to write about him I was prohibited from referring to him by name. Before that I had never given a thought to what a name was and what it meant. But I did so now, accentuated by the events that followed in the wake of the first book, and I began to write this chapter, first about the name itself, then about various names of literature and their function there, starting out with a piece of thinking I found in the writing of Ingeborg Bachmann concerning the decline of the name in literature, contained in a short essay in a book published a few years ago by Pax.

The essay on the name began on a right-hand page. On the left-hand page were some lines of a poem my eyes absently scanned when at some point during the spring I sat down with the book in front of me, intending to see if anything of what I had written had been unwittingly drawn from Bachmann’s essay.

So there are temples yet. A star probably still has light. Nothing, nothing is lost. These were the words I read. I guessed they were from a poem of Paul Celan.

And the concept of names is key to his theories in this section, in particular what he describes as the absence of a 'you' in the theories of German Nazism, and the removal of the identity as individuals of the victims of the holocaust.

The discussion is wide-roaming, with chains of association that are sometimes hard to remember - from Nazi Germany we suddenly find ourselves discussing Da Vinci's anatomical drawings or Holderlin's theories of language:

All it takes is one step and the world is transformed. One step and you enter the world of no names. It is blind, and you see the blindness. It is chaotic, and you see the chaos. It is beautiful, and you see the beauty. It is open, this is the open, and it is meaningless, this is the meaningless. It is also divine, indeed this is the divine. The little blue box with its red sun and the coarsened black surface of its sides, in whose interior the white matchsticks with their red, bead-like heads of phosphorus rest as if in a bed, is divine as it lies there motionless on the kitchen shelf with its thin covering of dust, faintly illuminated by the light of day outside the window, which slowly darkens as a black blanket of cloud drifts in over the city, and the first electrical charges snap through it at hurtling speed, following their unpredictable paths, thunder rumbling heavily in the sky. The wind as it picks up, and the rain that begins to fall, this is the divine. The hand that grasps the box, pushing the tiny bed out with the tip of an index finger to extract a matchstick, is a divine hand, and the fiery flame that flares up as the hand strikes the red phosphorus bead against the coarse surface, becoming, in the space of a second, a steady, much gentler flame, is the flame of the divine. Yet it burns in the shelter of our language, it burns in the shelter of our categories, it burns in the shelter of all the relations and connections those categories establish.

Interspersed with this, Knausgård also reconstructs Hitler's life up until his rise to power. He closely follows the account of [b:Hitler: 1889-1936 Hubris|93996|Hitler 1889-1936 Hubris (Hitler, #1)|Ian Kershaw|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1389660286s/93996.jpg|138544] by Kershaw, but takes a different approach and one consistent with that he takes in his own autobiography. Knausgård argues that when it comes to Hitler the way Kershaw portrays him, everything he does is either sinister or ridiculous, his accounts coloured by what we know Hitler would go on to do, whereas Knausgård goes back to many of Kershaw's original sources and shows how differently he was perceived at the time, how few clues there actually were as to what he would become.

It is tempting in 2018 to say this section is prescient when we have an American president tinkering with the tools of fascism and a socialist UK leader treading dangerously close to anti-semitism. However, that would be a mis-reading, again with hindsight, as if anything Knausgård's point is how remote the feelings of the 1930s are from our society today (i.e. 2011 for him): never has a society been further from revolution as our own, never has any human population been so comfortably dulled in hygge as our own.

At times I got rather bogged down in this part. The retold life story of Hitler and the detailed literary, linguistic and theological theories felt like two separate books, neither of which particularly belong in this novel. Although it must be said this Goodreads review - https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1074182183 - provides a fascinating theory as to why this section is actually the key to the whole novel.

I also can't help feel that others (Sebald, Tokarczuk, Enard) have done this erudite faction style of writing rather better. I found myself pining for the Knausgård of old, and it is fitting that the section ends with a signature combination:

I sat down again, poured myself some tepid coffee from the vacuum jug and lit another cigarette.

The final third of the volume takes us to publication day, but soon moves forward to the most difficult reader of all - his wife Linda who only reads the book after it is published. He knows there is much that is hurtful in the book, but admits that their relationship was at such a low ebb that the only reason I could write about it was that I had reached a point where I no longer had anything to lose. It made no difference if Linda read this, she could do what she liked. If she wanted to leave me, she could. I didn’t give a damn. I woke up unhappy, spent the day unhappy and went to bed unhappy.

While her short term reaction is to be upset, it seems manageable, but the true damage is done in the medium term. Linda, who has bipolar disorder, falls into a very deep depression, one ultimately requiring hospitalisation. This final section of the novel is brutally honest, highly personal and very moving as the young family comes to terms with the situation, and I can only say I hope Linda did have the chance to read it before publication.

But as my opening quote suggests, Knausgård finishes the novel, and he claimed his writing career, on an optimistic note.

Overall - for the novel as a whole - a triumph.

Malmö, Glemmingebro, 27 February 2008–2 September 2011

7 years later, it's 13.45 on 5th September 2018, and I would have to admit to a similar, albeit slight, sense of relief after finally reaching the end of the 3,966 page epic that is My Struggle, this final volume alone clocking in at 1,168 pages.

But that said, Min Kamp is one of the most important literary works of the 21st Century to date. The only book of comparable length I have read is Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu, which clocks in at 4,200 pages in the Moncrieff/Kilmartin/Enright translation, and the comparison is a fitting one.

It's also been a long wait for the English translation - Knausgård took only 3.5 years to write the entire series, but we've waited 7 years for the English version of book 6. His usual translator, Don Bartlett has assistance here from Martin Aitken, who translated the first half of this volume: the most notable style difference being that Aitken incorporates a number of Swedish / Norwegian words, in part reflecting I think the original where Knausgård slips between the two languages when addressing his children, but is does still seem distinctive versus the earlier works and the other half of this volume:

‘Också kram!’ said John. Me cuddle too.

or:

Plastic nets full of mussels lying on their bed of crushed ice. ‘Blåskjell. Mussels,’ I said. ‘What?’ she said. ‘Musslor,’ I said. ‘Blåmusslor.’

Book 6 brings the story of Knausgård's life up to date. It begins the day before the first of the books is to be published, and with two other books nearly complete, and, looking back to the start of the project, it spans the time up until the writing and completion of the book we are reading.

This makes for a more stimulating read than some of the earlier books. In those books Knausgård was adept at writing as he would have experienced and viewed the world at the time he was describing, without any ironic distance: book 4 he regards. looking back, as a success precisely because it is full of the terrible banality and vigour of youth, it is a comedy of immaturity, but that didn't make for a very stimulating read (my review https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1287483953). Here, the writer and the character are one and the same, a 40-something world-class novelist and literary theorist, and the book has much more intellectual heft.

The first volume was written in a black period for Knausgård , a cathartic work and a very introspective one:

Why had I written such things? I had been so despairing. It was as if I had been shut away inside myself, alone with my frustration, a dark and monstrous demon, which at some point had grown enormous, and as if there was no way out. Ever-decreasing circles. Greater and greater darkness. Not the existential kind of darkness that was all about life and death, overarching happiness or overarching grief, but the smaller kind, the shadow on the soul, the ordinary man’s private little hell, so inconsequential as to barely deserve mention, while at the same time engulfing everything.

But as this novel opens, he is confronting the reality that he has written a book, one that while a novel is a novel-without-fiction (as Javier Cercas would term it), about real people, some very close to him:

Four hundred and fifty pages, a story about my life centred around two events, the first being my mother and father splitting up, the second being my father’s death. The first three days after he was found. Names, places, events were all authentic. It wasn’t until I was about to send the manuscript to the people mentioned in it that I began to understand the consequences of what I had done.

And the reaction is worse than he had feared. His uncle Gunnar, his father's brother, who plays a key role in the first book, is particular incensed:

I spent half an hour talking to Geir Angell on the phone, ate a packet of cold fishcakes for lunch, made a fresh pot of coffee, and then when I came back in from the balcony there was an email from Gunnar.

The subject line said ‘Verbal rape’.

Gunnar aggressively challenges many of the facts in the book, not just his interpretation, and threatens to take legal action, obliging his publishers to instruct solicitors and to consider whether names need to be changed, passages omitted, the story even changed. At one point, Knausgård wonders if perhaps, as Gunnar suggests, the work is fictional, but:

If I accepted that perspective I would be obliterating myself. Not once had I considered myself to be exaggerating when writing about what had gone on in the house, not once had I considered myself to be exploiting dad and grandma, the events I was describing were too overwhelming for that, and what I was delving into was too important.

Although he does accept that he may have been harsh on his father, something he ultimately deals with by the (odd) approach of removing his father's name from the book:

I’d read a short novel by Peter Handke called A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, it was about his mother’s suicide and thereby autobiographical. In contrast to my own prose, which constantly leaned towards the emotional and evocative, Handke’s prose was dry and unsentimental. When I started writing I’d been trying to achieve a similar style, if not dry, then raw, in the sense of unrefined, direct, without metaphors or other linguistic decoration.

...

[But] I had written [...] in a way that was almost diametrically opposed to Handke’s, reaching continually towards affect, feeling, the sentimental in contrast to the rational, and dramatising my father, allowing him to be a character in a story, representing him in the same way as fictional characters are represented, by concealing the ‘as if’ on which all literature depends, and thereby traducing him and his integrity in the most basic of ways, by saying that this was him. I had said the same thing about all the novel’s characters, but only in the case of my father had I done so in a way that failed to show consideration to him and the person he was.

The first third of Part 6 (c450 pages, i.e. a long novel in itself) covers very little elapsed time, as Knausgård and his publishers work on how to present the novels, as well as dealing with the legal and reputation issues arising.

‘We put it out as a series of twelve. A book a month for a year. We could set up some kind of deal so people can subscribe and get the whole lot. What do you reckon?’ ‘It’s a fantastic idea!’ I said.

...

When he [called] it was to tell me they couldn’t make it work with twelve separate publications, there were too many practical problems and the figures wouldn’t add up. He suggested six instead. Three in the autumn, three the following spring.

Six books that weren’t independent of each other, that didn’t seem good to me. I needed to divide them differently so that each became a stand-alone book in its own right, which was to say I had to end up with six novels that could also be read as a single, continuous narrative. Doing it that way, the first book came to four hundred pages, the second to five hundred and fifty, and the third to three hundred. After that I ran out of material. If I was going to do it that way, I would have to write three new books in ten months. Which wasn’t implausible, I’d been doing about ten pages a day for the last six months as it was, in the region of fifty pages a week given the fact that I wasn’t allowed to work weekends.

That last 'wasn't allowed' is very telling - referring to an agreement with his wife that weekends are family time. He admits later in the book that his desire is to eliminate as much complexity as possible from his life - and family life is of course chaotic:

Why do I organise my life like this? What do I want with this neutrality? Obviously it is to eliminate as much resistance as possible, to make the days slip past as easily and unobtrusively as possible. But why? Isn’t that synonymous with wanting to live as little as possible? With telling life to leave me in peace so that I can … yes, well, what? Read? Oh, but come on, what do I read about, if not life? Write? Same thing. I read and write about life. The only thing I don’t want life for is to live it.

Interspersed with the publishing shenanigans are the signature Knausgård descriptions of life, here focused on the day-to-day details of living with three young children. For example, in the following paragraph that describes the next novel he was contemplating, one called (with anotherr obvious nod to Nazi Germany) The Third Realm:

‘The body, the blood’, ‘biology’, ‘the atom bomb’. And Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things had been appearing in my notes ever since the mid-90s. But it was a novel. It was. A world described through the material and the mechanical, sand, stone, shells, atoms, planets. No psychology, no feelings. A story that was different from ours, though similar. It was to be a dystopia, a novel about the final days, told by a man alone in a house, in the midst of a dry, warm landscape in late summer. And I had an ending ready, I had told it to Linda, who had lit up, it was sublime, amazing. It was!

‘OK, do you want your baths now?’ I said, returning the book to the shelf. The girls slid down from their chairs and skipped off to the bathroom. ‘Yes!’ cried John, and toddled after them.

He provides an eloquent justification for his minutely detailed approach in the novel:

A novel that was meant to say something true about reality could not be made too simple, it had to contain an element of exclusiveness in its communication, something not common to or shared by all, in other words something of its own, and there, at some point between the madman’s own particular and therefore uncommunicated ramblings, meaningless to everyone but the madman himself, who found them fascinatingly relevant, and the genre novel’s fixed formulations and clichés, which had become clichés by being familiar to everyone, was the domain of literature.

...

This was perhaps the greatest difficulty in writing autobiographically, finding out how material was relevant. In real life, of course, everything was relevant and in principle equal, since it was all there in existence at the same time – the great oil tankers at anchor in the Galtesund in the 70s, the plum tree outside my window, mum’s job at Kokkeplassen, dad’s face when he drove by in the car and I was out somewhere and saw him, the pond where we skated in winter, the smells inside the neighbours’ house, Dag Lothar’s mum that time she made milkshakes for us, the strange car that was parked one night down at Ubekilen, all the fish we had for dinner, the way the pine trees in next door’s garden swayed back and forth in the strong autumn winds, dad’s rage if I happened to dig my knee into the back of his seat in the car, the waffles we made every Tuesday, my great infatuation with Anne Lisbeth, the footballs mum and dad brought back for us from a trip to Germany, mine green with red hexagons, Yngve’s yellow with red hexagons, the way we stood one day and kicked them as high into the air as we could to see if they could reach the military helicopter that happened to come sweeping low over the playground.

But equally telling is a comment from his best friend:

‘You don’t have to say everything that comes into your mind, you know. Kids do that. Adults can put their utterances through quality control first.’

And my favourite example of oversharing - he tells us his PIN number and why he chose it.

So on to the middle section of the volume - perhaps the most infamous in the whole novel - the long essay on Hitler's Mein Kampf. The justification he gives for this is both the common name (although presumably this was not a coincidence?) but also his finding a Nazi pin in his late father's belongings then later a copy of Mein Kampf in his father's mother's.

Because the first book of this novel shares its name, My Struggle, with Hitler’s book, and because Hitler’s book and the Nazi pin were unexplained mysteries in that story, or perhaps not mysteries, but more exactly fields of the past that manifested themselves in the present and which I felt unable to trace back to anything I knew in that past, I had decided to write a few pages about Hitler’s book.

Although Knausgård is of course incapable of writing 'a few pages' and instead we get:

Four hundred pages about pre-war Vienna, Weimar between the wars, how times and psychology, art and politics are closely linked, and the formula for all things human, I-you-we-they-it.

This is primarily a highly literary treatment, one that for example opens not with Hitler at all, but with a 60 page detailed deconstruction of a poem by Celan.

So much of dad was collected in his name. He spelt it differently when he was young, and changed it sometime in his forties, and as he lay there dead and nameless, the name the mason chiselled into his headstone was spelt incorrectly. The stone is still there, in the cemetery in Kristiansand, with its misspelt name, on top of the interred urn containing the ashes of his body. And when, ten years later, I began to write about him I was prohibited from referring to him by name. Before that I had never given a thought to what a name was and what it meant. But I did so now, accentuated by the events that followed in the wake of the first book, and I began to write this chapter, first about the name itself, then about various names of literature and their function there, starting out with a piece of thinking I found in the writing of Ingeborg Bachmann concerning the decline of the name in literature, contained in a short essay in a book published a few years ago by Pax.

The essay on the name began on a right-hand page. On the left-hand page were some lines of a poem my eyes absently scanned when at some point during the spring I sat down with the book in front of me, intending to see if anything of what I had written had been unwittingly drawn from Bachmann’s essay.

So there are temples yet. A star probably still has light. Nothing, nothing is lost. These were the words I read. I guessed they were from a poem of Paul Celan.

And the concept of names is key to his theories in this section, in particular what he describes as the absence of a 'you' in the theories of German Nazism, and the removal of the identity as individuals of the victims of the holocaust.

The discussion is wide-roaming, with chains of association that are sometimes hard to remember - from Nazi Germany we suddenly find ourselves discussing Da Vinci's anatomical drawings or Holderlin's theories of language:

All it takes is one step and the world is transformed. One step and you enter the world of no names. It is blind, and you see the blindness. It is chaotic, and you see the chaos. It is beautiful, and you see the beauty. It is open, this is the open, and it is meaningless, this is the meaningless. It is also divine, indeed this is the divine. The little blue box with its red sun and the coarsened black surface of its sides, in whose interior the white matchsticks with their red, bead-like heads of phosphorus rest as if in a bed, is divine as it lies there motionless on the kitchen shelf with its thin covering of dust, faintly illuminated by the light of day outside the window, which slowly darkens as a black blanket of cloud drifts in over the city, and the first electrical charges snap through it at hurtling speed, following their unpredictable paths, thunder rumbling heavily in the sky. The wind as it picks up, and the rain that begins to fall, this is the divine. The hand that grasps the box, pushing the tiny bed out with the tip of an index finger to extract a matchstick, is a divine hand, and the fiery flame that flares up as the hand strikes the red phosphorus bead against the coarse surface, becoming, in the space of a second, a steady, much gentler flame, is the flame of the divine. Yet it burns in the shelter of our language, it burns in the shelter of our categories, it burns in the shelter of all the relations and connections those categories establish.

Interspersed with this, Knausgård also reconstructs Hitler's life up until his rise to power. He closely follows the account of [b:Hitler: 1889-1936 Hubris|93996|Hitler 1889-1936 Hubris (Hitler, #1)|Ian Kershaw|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1389660286s/93996.jpg|138544] by Kershaw, but takes a different approach and one consistent with that he takes in his own autobiography. Knausgård argues that when it comes to Hitler the way Kershaw portrays him, everything he does is either sinister or ridiculous, his accounts coloured by what we know Hitler would go on to do, whereas Knausgård goes back to many of Kershaw's original sources and shows how differently he was perceived at the time, how few clues there actually were as to what he would become.

It is tempting in 2018 to say this section is prescient when we have an American president tinkering with the tools of fascism and a socialist UK leader treading dangerously close to anti-semitism. However, that would be a mis-reading, again with hindsight, as if anything Knausgård's point is how remote the feelings of the 1930s are from our society today (i.e. 2011 for him): never has a society been further from revolution as our own, never has any human population been so comfortably dulled in hygge as our own.

At times I got rather bogged down in this part. The retold life story of Hitler and the detailed literary, linguistic and theological theories felt like two separate books, neither of which particularly belong in this novel. Although it must be said this Goodreads review - https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1074182183 - provides a fascinating theory as to why this section is actually the key to the whole novel.

I also can't help feel that others (Sebald, Tokarczuk, Enard) have done this erudite faction style of writing rather better. I found myself pining for the Knausgård of old, and it is fitting that the section ends with a signature combination:

I sat down again, poured myself some tepid coffee from the vacuum jug and lit another cigarette.

The final third of the volume takes us to publication day, but soon moves forward to the most difficult reader of all - his wife Linda who only reads the book after it is published. He knows there is much that is hurtful in the book, but admits that their relationship was at such a low ebb that the only reason I could write about it was that I had reached a point where I no longer had anything to lose. It made no difference if Linda read this, she could do what she liked. If she wanted to leave me, she could. I didn’t give a damn. I woke up unhappy, spent the day unhappy and went to bed unhappy.

While her short term reaction is to be upset, it seems manageable, but the true damage is done in the medium term. Linda, who has bipolar disorder, falls into a very deep depression, one ultimately requiring hospitalisation. This final section of the novel is brutally honest, highly personal and very moving as the young family comes to terms with the situation, and I can only say I hope Linda did have the chance to read it before publication.

But as my opening quote suggests, Knausgård finishes the novel, and he claimed his writing career, on an optimistic note.

Overall - for the novel as a whole - a triumph.