Take a photo of a barcode or cover

71 reviews for:

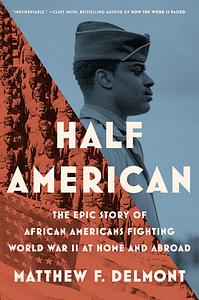

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad

Matthew F. Delmont

71 reviews for:

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad

Matthew F. Delmont

challenging

informative

medium-paced

informative

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced

Amazing book. It is still relevant to today and describes how WWII contributes to the racism in America today. I recommend everyone reads this book

challenging

emotional

informative

inspiring

fast-paced

informative

medium-paced

emotional

informative

inspiring

reflective

sad

medium-paced

dark

emotional

informative

medium-paced

challenging

informative

medium-paced

An excellent corrective to the false or partial history most U.S. citizens are taught in school. While the focus on WWII keeps the scope narrow, I sense there are still many untold stories the author could have highlighted in this book.

Among the many things I learned from this book, it really hit home how important all of the support staff were in WWII and how, in spite of the fact that many black folks were kept out of "combat roles" those jobs were just as dangerous and often required braving the line of fire to bring supplies to the front lines. In fact, while Germans were working with a ratio of one support role to one combat role, the Allies had a ratio of about three to one, ensuring the military was well-stocked.

There were, of course, many brave black fighters who flew as fighter pilots and fought on the front lines as well. Oftentimes these fighters showed incredible bravery, but even when recommended for military honors the petitions were either stalled completely or reduced to a lower honor to try to maintain the lie that black people are inferior to white people.

As a final note, I am grateful to this book because, although I am a fan of Langston Hughes, I didn't know that he went to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War as a political correspondent. This book led me to read some more of his poems about WWII and his work towards goal of double V-Day, meaning victory abroad against the Nazis and victory at home against our own fascist segregation.

Among the many things I learned from this book, it really hit home how important all of the support staff were in WWII and how, in spite of the fact that many black folks were kept out of "combat roles" those jobs were just as dangerous and often required braving the line of fire to bring supplies to the front lines. In fact, while Germans were working with a ratio of one support role to one combat role, the Allies had a ratio of about three to one, ensuring the military was well-stocked.

There were, of course, many brave black fighters who flew as fighter pilots and fought on the front lines as well. Oftentimes these fighters showed incredible bravery, but even when recommended for military honors the petitions were either stalled completely or reduced to a lower honor to try to maintain the lie that black people are inferior to white people.

As a final note, I am grateful to this book because, although I am a fan of Langston Hughes, I didn't know that he went to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War as a political correspondent. This book led me to read some more of his poems about WWII and his work towards goal of double V-Day, meaning victory abroad against the Nazis and victory at home against our own fascist segregation.

emotional

informative

inspiring

sad

medium-paced

This was a wrenching and inspiring look at the contributions of Black Americans in WWII and after.

Outstanding. Delmont employs clear-eyed writing and a double-pronged approach to narrate how black Americans fought racism at home and abroad and how this struggle laid the foundation for the CRM of the 1950s and 60s and the Black Lives Matter movement of the 2010s (because yes, BLM didn’t arise in summer 2020).

As Delmont writes, “stories [of World War II] that do not reckon with the Black American experience leave us ill prepared to understand the present. If we tell the right stories about the war, we can meet the resurgence of white supremacy as a deeply entrenched aspect of our country’s, political history and cultural life, rather than as a surprise or anomaly.”

Delmont deftly yet thoroughly illustrates the term “The Greatest Generation” is short-sighted and ironic at best: it elevates the service of white veterans who claimed to fight racism abroad while actively seeking to maintain the racist status quo at home through discrimination, violence, and pseudo-science. By stressing the role that the black press played in telling the stories of black service members, which white journalists and the U. S. government actively chose not to tell—including the way in which the military (at all

levels) denied black men and women from participating in combat roles; spread lies about their fitness for service; erased the impact they had in essential transportation and supply logistics that made so many offensives possible; and, supported verbal and physical harassment and violence against black veterans, including state-sanctioned lynchings —Delmont proves how America’s nostalgia for the GG is deeply embedded in white supremacy and the refusal of many white Americans to seek and tell a complete picture of our modern history that isn’t rooted in American exceptionalism and moral superiority.

To be clear, Delmont doesn’t dismiss the sacrifice of white service members whose served in WW II; rather, he removes the veneer that white veterans were committed to creating a world of equality and freedom for everyone, especially at home.

A must-read for: 1) those who want to understand why racism and its economic, political, and social effects are not an anomaly today; and 2) those who regard WW II as the epitome of America’s moral high ground

As Delmont writes, “stories [of World War II] that do not reckon with the Black American experience leave us ill prepared to understand the present. If we tell the right stories about the war, we can meet the resurgence of white supremacy as a deeply entrenched aspect of our country’s, political history and cultural life, rather than as a surprise or anomaly.”

Delmont deftly yet thoroughly illustrates the term “The Greatest Generation” is short-sighted and ironic at best: it elevates the service of white veterans who claimed to fight racism abroad while actively seeking to maintain the racist status quo at home through discrimination, violence, and pseudo-science. By stressing the role that the black press played in telling the stories of black service members, which white journalists and the U. S. government actively chose not to tell—including the way in which the military (at all

levels) denied black men and women from participating in combat roles; spread lies about their fitness for service; erased the impact they had in essential transportation and supply logistics that made so many offensives possible; and, supported verbal and physical harassment and violence against black veterans, including state-sanctioned lynchings —Delmont proves how America’s nostalgia for the GG is deeply embedded in white supremacy and the refusal of many white Americans to seek and tell a complete picture of our modern history that isn’t rooted in American exceptionalism and moral superiority.

To be clear, Delmont doesn’t dismiss the sacrifice of white service members whose served in WW II; rather, he removes the veneer that white veterans were committed to creating a world of equality and freedom for everyone, especially at home.

A must-read for: 1) those who want to understand why racism and its economic, political, and social effects are not an anomaly today; and 2) those who regard WW II as the epitome of America’s moral high ground