You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

slow-paced

Written more like a spy novel than a history book, this is a captivating and well researched summary of an incredibly chaotic time.

Shilts puts all of the major players involved with the outbreak of AIDS into context, from the well meaning, but underfunded government doctors and researchers to the gay activists who are emboldened by recent political successes but scared of doing anything to reverse them.

The length and density of the book had scared me off for months, but I found that the book felt much lighter once I actually began reading it. Individual sections could be read on their own, however the connections Shilts makes throughout the book between seemingly disparate people and events make the book so much interesting and valuable as a historical record. This should be required reading for every gay man, to better understand how our community came to be, and how many people were sacrificed for the freedom we now enjoy.

Shilts puts all of the major players involved with the outbreak of AIDS into context, from the well meaning, but underfunded government doctors and researchers to the gay activists who are emboldened by recent political successes but scared of doing anything to reverse them.

The length and density of the book had scared me off for months, but I found that the book felt much lighter once I actually began reading it. Individual sections could be read on their own, however the connections Shilts makes throughout the book between seemingly disparate people and events make the book so much interesting and valuable as a historical record. This should be required reading for every gay man, to better understand how our community came to be, and how many people were sacrificed for the freedom we now enjoy.

This book took me nearly a year to read, and I'm not sure why. Maybe because the topic was so heavy that I couldn't handle it some days. Maybe because I always forgot how not intimidating it actually is to read. And The Band Played On is an excellent, wildly thorough dive into the early days of the AIDS epidemic, and why the response was so poor to it. There's so much science and nuance and heart, and at all times it feels accessible. I deeply appreciated how often Shilts reminded you who people were or what certain illnesses were.

I'm also glad I read this after the COVID pandemic began. It was very interesting to see what we did better (coordinated response! funds!) and where history repeated itself (fauci! people acting against their own self interest!). At times it hit too close to home.

Overall, I could not recommend this book enough to those who want to know more about the origins of AIDS and the earliest days of its arrival.

I'm also glad I read this after the COVID pandemic began. It was very interesting to see what we did better (coordinated response! funds!) and where history repeated itself (fauci! people acting against their own self interest!). At times it hit too close to home.

Overall, I could not recommend this book enough to those who want to know more about the origins of AIDS and the earliest days of its arrival.

dark

emotional

informative

slow-paced

4⭐

Heart-breaking, anger-inducing, powerful.

First, I have to say, listening to this through Audible was absolutely needed for me. I'm not downplaying Randy Shilts' writing, but it tended to border on drudgery.

That all said, this was an absolutely sweeping work of reportage that documents this emergence, response, and experiences of the AIDS epidemic in the early- to mid-1980s. One thing that makes this such a wonderful work of nonfiction is that Shilts documents, not only what was occurring in the United States, but on the global scale. He masterfully puts various narratives and perspectives into a fairly linear chronological schema, displaying the facts and emotions that were rampant during this time of uncertainty.

This was a bit of a slog, but the overall work was absolutely essential for any person of the LGBTQIA+ community. It's important to understand, recognize, and respect our predecessors' history to build upon their legacies. I'm so grateful to have read this.

Heart-breaking, anger-inducing, powerful.

First, I have to say, listening to this through Audible was absolutely needed for me. I'm not downplaying Randy Shilts' writing, but it tended to border on drudgery.

That all said, this was an absolutely sweeping work of reportage that documents this emergence, response, and experiences of the AIDS epidemic in the early- to mid-1980s. One thing that makes this such a wonderful work of nonfiction is that Shilts documents, not only what was occurring in the United States, but on the global scale. He masterfully puts various narratives and perspectives into a fairly linear chronological schema, displaying the facts and emotions that were rampant during this time of uncertainty.

This was a bit of a slog, but the overall work was absolutely essential for any person of the LGBTQIA+ community. It's important to understand, recognize, and respect our predecessors' history to build upon their legacies. I'm so grateful to have read this.

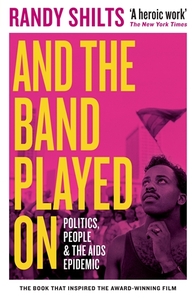

A detailed timeline of the AIDS epidemic, from its North American superspreader event in New York City in 1976 through the Rock Hudson media explosion in 1985. Written by a gay San Franciscan journalist, Randy Shilts, who died of AIDS in the 1990s. The thoroughness of this account lends it much of its power -- by reading 600 pages of the frustrations, roadblocks, and bigotry that prevented action on AIDS for five years, you feel like you're experiencing it firsthand. I also appreciated all the people who worked on AIDS in a thousand tiny, dedicated ways; those folks are the only reason the crisis wasn't worse.

Key Players

The narrative unfurls through the lives of key players, who fall into a variety of groups: (1) government researchers, public health officials, and front-line doctors; (2) local, state, and national politicians; (3) activists of the gay liberation and gay rights movements; (4) AIDS sufferers, their lovers, and their community.

AIDS Scientists and Public Health Officials

One of the major struggles of the AIDS crisis was within the scientific community. Rather than collaborating readily and openly, United States government agencies fought one another for influence and recognition, slowing progress. In particular, the National Cancer Institute (esp. Bob Gallo) and the Centers for Disease Control (esp. Don Francis and Dale Lawrence) were often at loggerheads. The Reagan Administration's austerity measures forced government agencies within the same Department to steal funding from one another: Instead of increasing the size of the pie, the Administration just made the Department Secretary change how the pie was cut. It created perverse incentives among government scientists, stifling collaboration. According to Shilts' account, the NCI also refused open collaboration with world-class researchers at the French Pasteur Institute (esp. Francoise Bar, Luc Montagnier), eventually stealing recognition for the discovery of the AIDS virus and embittering their relationship.

It's worth highlighting the dedicated work of San Francisco scientists and public servants Selma Dritz (SF Department of Public Health), Sandra Ford (US CDC), and Marcus Conant (UC San Francisco). In a narrative with so much frustration and despair, it was really lovely to see people who worked so hard on the issue.

Politicians

To discuss later:

BRANDT, HECKLER

SILVERMAN, SENCER

MILK, FEINSTEIN, PALOSI

Activists

In San Francisco, the Alice B. Toklas Democratic Club and the Harvey Milk Gay Democratic Club were often at odds, due to their diametrically opposed ideas on queer identity (Are we fundamentally the same as heterosexuals, except for who we love? or are we fundamentally different?) and coming out (Is staying in the closet the best move for everyone? or is it holding us back, personally and as a community?). They similarly struggled over the appropriate response to the AIDS crisis.

San Franciscan gays still responded better than New York City gays -- In New York City, Gay Men's Health Crisis only fought for retrospective solutions, rather than aggressive preventatives. GMHC had similar internal struggles as the disputes between the Toklas and Milk Clubs in SF; the head of one faction, Larry Kramer, eventually formed ACT UP New York.

AIDS Sufferers, Their Lovers, and Their Community

Shilts weaves stories of queer community members--both those suffering from AIDS and those who love them--into the narrative everywhere. Particularly moving were the stories of Gary Walsh, Lu Chaikin, and Matt Krieger. I also loved the story of Frances Borchelt, an early transfusion AIDS case, and her family.

Central Struggles

(1) Federal government financing & bureaucratic hurdles; scientists fighting over funding and recognition; competitive spirit in science that is not helpful towards progress.

(2) Changing the high-risk sexual behaviors in gay communities was difficult due to a standard gay fear response (fear of homophobic persecution; reactive responses to abuse triggers); more evidence that bigotry hurts everyone, including the perpetrators.

(3) Disputes between public health and blood bank testing; blood banks put off testing blood for the longest time due to the cost, regardless of impact to recipients (esp. hemophiliacs).

(4) Piss-poor science communication due to the American fear/disgust of discussing sex. Science communicators didn't want to provide specific safe-sex guidance because that would be (a) too profane for public communications and (b) condoning sex outside marriage, and homosexual sex, and we can't have that. The primary real risk factor was "semen and blood," but this was transformed by "AIDSpeak" into "bodily fluids," which was then widely interpreted as "spit, etc." This created an unnecessary environment of straight hysteria and fear, which increased homophobic bigotry and inhumane treatment of AIDS sufferers by clinical staff.

(5) The struggle to get AIDS/HIV recognized as a threat to public health worth fighting; in the first several years of the epidemic, the risk groups were homosexuals, Haitians, hemophiliacs, and heroin addicts, all groups of people maligned by the mainstream. The struggle against AIDS didn't become serious on a national scale until straights and the rich/famous were at risk. Without substantial and sustained media coverage, the government felt no pressure to take the crisis seriously as an issue. When media coverage finally exploded in 1985, the epidemic received a proper and intense government response, because the administration was forced to -- but by that point, it was too late to do much to contain the spread.

My experience of the COVID-19 pandemic over the last three years gave me a foothold to better understand the failures of the government response to AIDS, and to better understand the fear of communities vulnerable to HIV/AIDS. I think, prior to experiencing COVID, the slowness of the government response to AIDS might have struck me as more normal bureaucratic bullshit, but after experiencing COVID-19, I know what a speedy government response can and should look like. The difference between the two is clearly (a) a matter of caring about the vulnerable groups; and (b) the kind of administration in power at the time. (This is not to say the government response to COVID-19 was perfect -- just to say that it was swift and decisive, in comparison with the AIDS response.)

Parallels to Climate Change

While I expected the ample parallels with the COVID-19 epidemic, I was caught off-guard by the parallels to climate change:

* A problem with a long latency period between behavior (cause) and impact (effect), and thus the struggle for people to understand the issue and act upon it -- distance between behavior change and reaping the benefits makes it difficult for us (humans) to handle.

* A problem that affects underclasses more than upper classes, but will affect everyone eventually -- but because of who it effects, it is largely ignored as an issue and unaddressed. Causes preventable suffering.

* Causes and risk factors identified relatively early; scientists project specific actions that can improve future prospects; not heeded.

Misc Thoughts

A few elements not covered, related to my personal knowledge of AIDS before I started reading: (1) Ryan White, an HIV transfusion case in South Bend, Indiana, who was refused treatment and denigrated because of his diagnosis; (2) Princess Diana's visit to the AIDS ward of a hospital, wherein she shook hands with, spoke with, and listened to AIDS sufferers without PPE, to try to suppress hysteria about "casual contact" transmission; (3) ACT UP New York, started by Larry Kramer, and the NAMES Project Quilt, started by Cleve Jones, both as responses to the despair, inaction, and death of the crisis; (4) the Reagan Administration's Press Secretary deriding reporters who asked about the AIDS crisis with homophobic jokes. All items weren't covered because they were later developments (after book publication).

Gay Community Responses to AIDS

History teachers sometimes frame activism along an axis with two diametrically-opposed poles (rage and intense demonstrations vs. non-violent civil disobedience), with only one approach being the "right" one. That's too simplistic of a framing. Those aren't the only two possible responses, and ALL the possible responses to a crisis are needed to survive it: You need the rageful activists who confront and shame institutions of power (e.g., ACT UP NY); the non-violent civil disobedience activists, who clearly and calmly demonstrate demands and who appear to be the "sensible alternative" to work with, compared to the former group (e.g., Harvey Milk Club, etc); the volunteer community-support activists, who help the oppressed community survive the struggle (e.g., the Shanti Project); the scientists and government insiders who work on the cause and push politicians and decision makers to do more; journalists who investigate and report on internal dealings; and the artist activists, who help the community grieve, process their emotions, heal their wounds, and find the strength and joy necessary to go on (e.g., the NAMES Project Quilt). There are many, many ways to respond to a crisis, and the more I read of history and activist movements, the more I'm convinced that a community needs people working on every approach.

Issues with Bias & Villainization

* To be added later:

GAETAN DUGAS

BOB GALLO

Next Reads:

* [b:The Secret Epidemic: The Story of AIDS and Black America|10249|The Secret Epidemic The Story of AIDS and Black America|Jacob Levenson|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1320437649l/10249._SY75_.jpg|12968]

* [b:Poets for Life: Seventy-Six Poets Respond to AIDS|450811|Poets for Life Seventy-Six Poets Respond to AIDS|Michael Klein|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1347602731l/450811._SY75_.jpg|2222314]

* [b:Between Certain Death and a Possible Future: Queer Writing on Growing up with the AIDS Crisis|50371422|Between Certain Death and a Possible Future Queer Writing on Growing up with the AIDS Crisis|Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1618150708l/50371422._SX50_.jpg|75323947]

Key Players

The narrative unfurls through the lives of key players, who fall into a variety of groups: (1) government researchers, public health officials, and front-line doctors; (2) local, state, and national politicians; (3) activists of the gay liberation and gay rights movements; (4) AIDS sufferers, their lovers, and their community.

AIDS Scientists and Public Health Officials

One of the major struggles of the AIDS crisis was within the scientific community. Rather than collaborating readily and openly, United States government agencies fought one another for influence and recognition, slowing progress. In particular, the National Cancer Institute (esp. Bob Gallo) and the Centers for Disease Control (esp. Don Francis and Dale Lawrence) were often at loggerheads. The Reagan Administration's austerity measures forced government agencies within the same Department to steal funding from one another: Instead of increasing the size of the pie, the Administration just made the Department Secretary change how the pie was cut. It created perverse incentives among government scientists, stifling collaboration. According to Shilts' account, the NCI also refused open collaboration with world-class researchers at the French Pasteur Institute (esp. Francoise Bar, Luc Montagnier), eventually stealing recognition for the discovery of the AIDS virus and embittering their relationship.

It's worth highlighting the dedicated work of San Francisco scientists and public servants Selma Dritz (SF Department of Public Health), Sandra Ford (US CDC), and Marcus Conant (UC San Francisco). In a narrative with so much frustration and despair, it was really lovely to see people who worked so hard on the issue.

Politicians

To discuss later:

BRANDT, HECKLER

SILVERMAN, SENCER

MILK, FEINSTEIN, PALOSI

Activists

In San Francisco, the Alice B. Toklas Democratic Club and the Harvey Milk Gay Democratic Club were often at odds, due to their diametrically opposed ideas on queer identity (Are we fundamentally the same as heterosexuals, except for who we love? or are we fundamentally different?) and coming out (Is staying in the closet the best move for everyone? or is it holding us back, personally and as a community?). They similarly struggled over the appropriate response to the AIDS crisis.

San Franciscan gays still responded better than New York City gays -- In New York City, Gay Men's Health Crisis only fought for retrospective solutions, rather than aggressive preventatives. GMHC had similar internal struggles as the disputes between the Toklas and Milk Clubs in SF; the head of one faction, Larry Kramer, eventually formed ACT UP New York.

AIDS Sufferers, Their Lovers, and Their Community

Shilts weaves stories of queer community members--both those suffering from AIDS and those who love them--into the narrative everywhere. Particularly moving were the stories of Gary Walsh, Lu Chaikin, and Matt Krieger. I also loved the story of Frances Borchelt, an early transfusion AIDS case, and her family.

Central Struggles

(1) Federal government financing & bureaucratic hurdles; scientists fighting over funding and recognition; competitive spirit in science that is not helpful towards progress.

(2) Changing the high-risk sexual behaviors in gay communities was difficult due to a standard gay fear response (fear of homophobic persecution; reactive responses to abuse triggers); more evidence that bigotry hurts everyone, including the perpetrators.

(3) Disputes between public health and blood bank testing; blood banks put off testing blood for the longest time due to the cost, regardless of impact to recipients (esp. hemophiliacs).

(4) Piss-poor science communication due to the American fear/disgust of discussing sex. Science communicators didn't want to provide specific safe-sex guidance because that would be (a) too profane for public communications and (b) condoning sex outside marriage, and homosexual sex, and we can't have that. The primary real risk factor was "semen and blood," but this was transformed by "AIDSpeak" into "bodily fluids," which was then widely interpreted as "spit, etc." This created an unnecessary environment of straight hysteria and fear, which increased homophobic bigotry and inhumane treatment of AIDS sufferers by clinical staff.

(5) The struggle to get AIDS/HIV recognized as a threat to public health worth fighting; in the first several years of the epidemic, the risk groups were homosexuals, Haitians, hemophiliacs, and heroin addicts, all groups of people maligned by the mainstream. The struggle against AIDS didn't become serious on a national scale until straights and the rich/famous were at risk. Without substantial and sustained media coverage, the government felt no pressure to take the crisis seriously as an issue. When media coverage finally exploded in 1985, the epidemic received a proper and intense government response, because the administration was forced to -- but by that point, it was too late to do much to contain the spread.

My experience of the COVID-19 pandemic over the last three years gave me a foothold to better understand the failures of the government response to AIDS, and to better understand the fear of communities vulnerable to HIV/AIDS. I think, prior to experiencing COVID, the slowness of the government response to AIDS might have struck me as more normal bureaucratic bullshit, but after experiencing COVID-19, I know what a speedy government response can and should look like. The difference between the two is clearly (a) a matter of caring about the vulnerable groups; and (b) the kind of administration in power at the time. (This is not to say the government response to COVID-19 was perfect -- just to say that it was swift and decisive, in comparison with the AIDS response.)

Parallels to Climate Change

While I expected the ample parallels with the COVID-19 epidemic, I was caught off-guard by the parallels to climate change:

* A problem with a long latency period between behavior (cause) and impact (effect), and thus the struggle for people to understand the issue and act upon it -- distance between behavior change and reaping the benefits makes it difficult for us (humans) to handle.

* A problem that affects underclasses more than upper classes, but will affect everyone eventually -- but because of who it effects, it is largely ignored as an issue and unaddressed. Causes preventable suffering.

* Causes and risk factors identified relatively early; scientists project specific actions that can improve future prospects; not heeded.

Misc Thoughts

A few elements not covered, related to my personal knowledge of AIDS before I started reading: (1) Ryan White, an HIV transfusion case in South Bend, Indiana, who was refused treatment and denigrated because of his diagnosis; (2) Princess Diana's visit to the AIDS ward of a hospital, wherein she shook hands with, spoke with, and listened to AIDS sufferers without PPE, to try to suppress hysteria about "casual contact" transmission; (3) ACT UP New York, started by Larry Kramer, and the NAMES Project Quilt, started by Cleve Jones, both as responses to the despair, inaction, and death of the crisis; (4) the Reagan Administration's Press Secretary deriding reporters who asked about the AIDS crisis with homophobic jokes. All items weren't covered because they were later developments (after book publication).

Gay Community Responses to AIDS

History teachers sometimes frame activism along an axis with two diametrically-opposed poles (rage and intense demonstrations vs. non-violent civil disobedience), with only one approach being the "right" one. That's too simplistic of a framing. Those aren't the only two possible responses, and ALL the possible responses to a crisis are needed to survive it: You need the rageful activists who confront and shame institutions of power (e.g., ACT UP NY); the non-violent civil disobedience activists, who clearly and calmly demonstrate demands and who appear to be the "sensible alternative" to work with, compared to the former group (e.g., Harvey Milk Club, etc); the volunteer community-support activists, who help the oppressed community survive the struggle (e.g., the Shanti Project); the scientists and government insiders who work on the cause and push politicians and decision makers to do more; journalists who investigate and report on internal dealings; and the artist activists, who help the community grieve, process their emotions, heal their wounds, and find the strength and joy necessary to go on (e.g., the NAMES Project Quilt). There are many, many ways to respond to a crisis, and the more I read of history and activist movements, the more I'm convinced that a community needs people working on every approach.

Issues with Bias & Villainization

* To be added later:

GAETAN DUGAS

BOB GALLO

Next Reads:

* [b:The Secret Epidemic: The Story of AIDS and Black America|10249|The Secret Epidemic The Story of AIDS and Black America|Jacob Levenson|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1320437649l/10249._SY75_.jpg|12968]

* [b:Poets for Life: Seventy-Six Poets Respond to AIDS|450811|Poets for Life Seventy-Six Poets Respond to AIDS|Michael Klein|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1347602731l/450811._SY75_.jpg|2222314]

* [b:Between Certain Death and a Possible Future: Queer Writing on Growing up with the AIDS Crisis|50371422|Between Certain Death and a Possible Future Queer Writing on Growing up with the AIDS Crisis|Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1618150708l/50371422._SX50_.jpg|75323947]

A comprehensive picture of all the parts of society, from the inattentive media to the miserly executive office, that failed together in their response to AIDS in its first years. Repetitive, but that speaks more to the unfortunate resistance to changing approaches to the epidemic than the book itself.

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

inspiring

reflective

sad

slow-paced

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

reflective

sad

tense

medium-paced

So readable for being such a huge book with an enormous scope. I read it with a heavy heart, and it was as hard to process as the current pandemic is to watch unfold. But I feel like it was well worth the effort.

I would like the post-1985 story sequel.

I would like the post-1985 story sequel.