You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

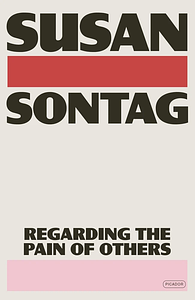

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

dark

emotional

informative

sad

medium-paced

What can we learn from depictions of others’ pain, be it war or terror or otherwise?

Why do some of us find satisfaction in stomaching gruesome images?

Is it exploitative to view others’ pain in a gallery, removed from the scene?

What types of suffering aren’t depicted?

‘What does it mean to protest suffering, as distinct from acknowledging it?’

Regrettably (and through my own fault), I have forgotten most of what I was taught in school about historic events geographically removed from me. But photographs of the non-cityscapes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and a lone toddler in the destruction left by the Rape of Nanking have been engraved in my brain ever since. This book (essay) addressed some of my anxieties regarding photographed cruelties, both historic and current, and provided some new arguments to explore.

“To remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture. ... Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. But they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.”

“Photographs that everyone recognizes are now a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares that it has chosen to think about. .. What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.”

“Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers. .. People don't become inured to what they are shown – if that's the right way to describe what happens – because of the quantity of images dumped on them. It is passivity that dulls feeling. The states described as apathy, moral or emotional anesthesia, are full of feelings; the feelings are rage and frustration.”

“So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence. To that extent, it can be (for all our good intentions) an impertinent – if not an inappropriate – response. To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering, and may - in ways we might prefer not to imagine - be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”

“Perhaps too much value is assigned to memory, not enough to thinking. Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself. .. But history gives contradictory signals about the value of remembering in the much longer span of a collective history. There is simply too much injustice in the world. And too much remembering (of ancient grievances: Serbs, Irish) embitters. To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited. If the goal is having some space in which to live one's own life, then it is desirable that the account of specific injustices dissolve into a more general understanding that human beings everywhere do terrible things to one another.”

“To remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture. ... Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. But they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.”

“Photographs that everyone recognizes are now a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares that it has chosen to think about. .. What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.”

“Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers. .. People don't become inured to what they are shown – if that's the right way to describe what happens – because of the quantity of images dumped on them. It is passivity that dulls feeling. The states described as apathy, moral or emotional anesthesia, are full of feelings; the feelings are rage and frustration.”

“So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence. To that extent, it can be (for all our good intentions) an impertinent – if not an inappropriate – response. To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering, and may - in ways we might prefer not to imagine - be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”

“Perhaps too much value is assigned to memory, not enough to thinking. Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself. .. But history gives contradictory signals about the value of remembering in the much longer span of a collective history. There is simply too much injustice in the world. And too much remembering (of ancient grievances: Serbs, Irish) embitters. To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited. If the goal is having some space in which to live one's own life, then it is desirable that the account of specific injustices dissolve into a more general understanding that human beings everywhere do terrible things to one another.”

¿Qué tan sencibles somos al ver una fotografía que muestra el sufrimiento, muerte, guerra, violencia en los otros? ¿Si veo la fotografía que debe causarme? ¿Si la ignoro soy indiferente al dolor de los demás? Estas y otras preguntas me deja este libro.

challenging

emotional

informative

reflective

medium-paced

challenging

dark

informative

inspiring

reflective

fast-paced

informative

medium-paced

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

reflective

slow-paced

informative

reflective

medium-paced

Fairly dense for such a short book. Based on the description, I expected this to go in a different direction than it ended up going, in that much of it was writing about the history of photographic documentation of human suffering in response to war, and its relationship to historical depictions of suffering in art. Where references are usually insightful and inspiring, often they were so profuse that it was actually bogging down my comprehension a bit. Love the way she wrapped up the last few chapters of the book, talking about the psychological effects of digesting the horror of reality. Going to reality-test with this one: "Someone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists, who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood. No one after a certain age has the right to this kind of innocence, of superficiality, to this degree of ignorance, or amnesia (114)."

read this for class in one day on top of like 70 pages of other reading but very very thought provoking, especially now as we watch a genocide unfold on social media. much to think about.