Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Personally, the problem I have with postmodernism is that, as far as I am concerned, I do not have the necessity of “freedom” that postmodernist theorists insist upon granting me as a reader. I read principally in order to entertain myself at the same time that I learn something new; whether it is about some historical past, an exotic culture unknown to me, a mind-blowing political theory or, in the case of fiction, just for the sake of peeping into other people's minds and thoughts.

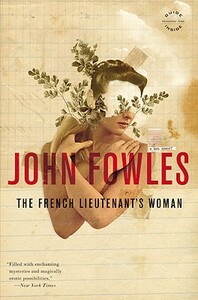

In other words, I am not at all concerned with my freedom as a reader, since what I enjoy is precisely the possibility of being the spectator of another reality. I have enough with all the decisions I have to take in my daily life without having to decide as well for the authors of the books I read. Pardon my trip down memory lane but here 'tis: when I was a kid there was this craze of the “Choose your own adventure” books. It was not a bad idea, the fact that you could read a book in the same way that you played a game. I hope the comparison it is not too far-fetched but now I see it was like postmodernism but without any of the academicism. You were “granted power”, as a postmodernist would say, you “pulled the strings!” as Bela Lugosi in Ed Wood's "Glen or Glenda" put it. Eventually, though, after three or four times of playing/reading it turned up to be pretty boring. Maybe it is because they were awfully written, not even literature to start with, but I reckon it also has something to do with the fact that not having a solid story-line made them a disordered mess. All in all, as young as I was, it was the first time that I realized that, in literature (or whatever that was) I did not want to be granted power to decide. The same goes for The French Lieutenant’s women. This idea of giving freedom to both the reader as well as the characters (what Richard P. Lynch calls “narrative freedom”) it is in fact just a game for the author, an illusion, as Fowles himself recognised in a 1974 interview with James Campbell. Ultimately it is always the author who decides on his/her character’s imaginary lives no matter what he/she says or tries to accomplish stylistically.

I think that the notion that texts are an entity completely independent of the author that can be given back to the reader (“The death of the author” as the french literary critic Roland Barthes put it) it is useful in literary and academic circles in order to study the different relations that are established between author and the reader, and I suppose also to question the whole idea of the former as a power figure (a tyrant, an “authority”) but ultimately I do not think it is realistic. Readers already have a certain amount of power: they can read fast, slow, pause -in order to meditate on something-, abandon a book completely, etc. But pretending that they have a saying in the fate of the characters is a different thing altogether.

To my way of thinking texts are a product of an author's mind and, even in the most imaginative fiction, they convey some of the author's outlook. As readers, we not only enjoy an imaginative plot or twist but also the fact that we have been made accomplices of the author's psyche. This is why we usually enjoy works that are written by authors whose attitude to life and way of thinking are similar to our own. We feel connected to them so we trust them as we would trust a close relative. We learn from them, we let them give us advise, and their ideas help us to change wrong preconceptions or, even, to reassert some ideas that we previously had. There is a beautiful quote by Kurt Vonnegut that summarizes this idea: “Many people need desperately to receive this message: 'I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.” So, I ruminate, what's the point of letting the authors granting us control as if we were always right? I like to think that we need them, but not as some kind of iron-heel dictators, but as smart and really talkative drinking buddies. Having said that, I got to say that I would definitely go on a pub crawl with some of my favorite authors such as the aforementioned Vonnegut, H.G. Wells, George Orwell or John Fante, but I don't think I would go out drinking with Woolf or Joyce, if you get what I mean. So no postmodernist experiments for me, please. Give me that old-time story line.

In other words, I am not at all concerned with my freedom as a reader, since what I enjoy is precisely the possibility of being the spectator of another reality. I have enough with all the decisions I have to take in my daily life without having to decide as well for the authors of the books I read. Pardon my trip down memory lane but here 'tis: when I was a kid there was this craze of the “Choose your own adventure” books. It was not a bad idea, the fact that you could read a book in the same way that you played a game. I hope the comparison it is not too far-fetched but now I see it was like postmodernism but without any of the academicism. You were “granted power”, as a postmodernist would say, you “pulled the strings!” as Bela Lugosi in Ed Wood's "Glen or Glenda" put it. Eventually, though, after three or four times of playing/reading it turned up to be pretty boring. Maybe it is because they were awfully written, not even literature to start with, but I reckon it also has something to do with the fact that not having a solid story-line made them a disordered mess. All in all, as young as I was, it was the first time that I realized that, in literature (or whatever that was) I did not want to be granted power to decide. The same goes for The French Lieutenant’s women. This idea of giving freedom to both the reader as well as the characters (what Richard P. Lynch calls “narrative freedom”) it is in fact just a game for the author, an illusion, as Fowles himself recognised in a 1974 interview with James Campbell. Ultimately it is always the author who decides on his/her character’s imaginary lives no matter what he/she says or tries to accomplish stylistically.

I think that the notion that texts are an entity completely independent of the author that can be given back to the reader (“The death of the author” as the french literary critic Roland Barthes put it) it is useful in literary and academic circles in order to study the different relations that are established between author and the reader, and I suppose also to question the whole idea of the former as a power figure (a tyrant, an “authority”) but ultimately I do not think it is realistic. Readers already have a certain amount of power: they can read fast, slow, pause -in order to meditate on something-, abandon a book completely, etc. But pretending that they have a saying in the fate of the characters is a different thing altogether.

To my way of thinking texts are a product of an author's mind and, even in the most imaginative fiction, they convey some of the author's outlook. As readers, we not only enjoy an imaginative plot or twist but also the fact that we have been made accomplices of the author's psyche. This is why we usually enjoy works that are written by authors whose attitude to life and way of thinking are similar to our own. We feel connected to them so we trust them as we would trust a close relative. We learn from them, we let them give us advise, and their ideas help us to change wrong preconceptions or, even, to reassert some ideas that we previously had. There is a beautiful quote by Kurt Vonnegut that summarizes this idea: “Many people need desperately to receive this message: 'I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.” So, I ruminate, what's the point of letting the authors granting us control as if we were always right? I like to think that we need them, but not as some kind of iron-heel dictators, but as smart and really talkative drinking buddies. Having said that, I got to say that I would definitely go on a pub crawl with some of my favorite authors such as the aforementioned Vonnegut, H.G. Wells, George Orwell or John Fante, but I don't think I would go out drinking with Woolf or Joyce, if you get what I mean. So no postmodernist experiments for me, please. Give me that old-time story line.

This book gave me an entryway into Victorian literature as after I read it I found reading books that were actually written in the Victorian era much easier to decipher. I disliked Charles' perspective and would love to have read from Sarah's point of view, but alas I see that would have ruined the mystery. The painting of Sarah as something devilish does shed life on the ideologies of the time, but it made me uncomfortable when reading it the way Charles would change his thoughts on her in a flash.

Thank goodness it's over and I finally finished it. I enjoyed the way it was written with the author popping in to express his thoughts and opinions but didn't enjoy the turgid characters, lumbering melodrama, or the many Victorian sociology lectures. Glad to be done.

challenging

slow-paced

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I can understand what this book is trying to do, and it is very interesting to read such a self conscious author offering different endings and questioning everything he does etc.

however, I felt that it was a bit clumsy and could have been done more nicely. Arguably this is the point of the book, to trip you up from getting too absorbed into the story, however, it spoiled my enjoyment somewhat. I felt as if he had a word count and was just filling up space by adding in random details and endings. It took me a long time to read just because I could not get into it.

I understand Fowles' motives and I do find it very interesting, I just did not enjoy it. That's the reason behind my star rating. I just wish I could have loved it.

however, I felt that it was a bit clumsy and could have been done more nicely. Arguably this is the point of the book, to trip you up from getting too absorbed into the story, however, it spoiled my enjoyment somewhat. I felt as if he had a word count and was just filling up space by adding in random details and endings. It took me a long time to read just because I could not get into it.

I understand Fowles' motives and I do find it very interesting, I just did not enjoy it. That's the reason behind my star rating. I just wish I could have loved it.

emotional

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I really enjoyed this book because it was very gripping yet not an on-the-edge-of-your-seat novel. The only part of this novel that I did not enjoy was the alternate endings. Some people would like this novel for that reason, claiming that they can choose their own ending. If you don't like the first ending, then choose the second one. However, I prefer my novels to have one clear and well defined ending. Other than that, however, this novel was a great read. Slightly frustrating at times yet consistently romantic, The French Lieutenant's Woman will leave you with a way to make the novel your own, by giving you the power to choose the way you want it to end.

This was such a goddamn trigger because of the context w/in which I was reading it that I actively began a Tumblr hashtag for it (#charlesyouasshole). Because forreal. CHARLES, YOU ASSHOLE. The invention of the Other, and the perfect Othering of Sarah in this book was specifically challenging to get through because of how true it rang. Wrt the author and wrt Charles. The male imagination necessitates the transformation of the woman-holding-on into an Ernestina, perhaps, so as to justify their perceptions and desires for the woman-to-be-pursued that is Sarah.

My proposed essay on The French Lieutenant’s Woman: A character sketch of Charles / the anatomy of a Victorian intellectual fuckboi / why men always need to justify the attractiveness of one woman at the expense of another.

Tbd: Narrative style that I thought was A++, the way Fowles creates a seamless amalgamation of multiple thought processes and points of entry. The most apt example of this is the scene where Ernestina is observing herself bashfully in the mirror and there is a comment about '...that odious prinny George the IV' and you halt for a second, perhaps, 'cause you're like, whoaaa there, Ernestina, finally showing some legitnessss. And then you realize it was the narrator-figure making a comment. Not to be confused with the author-figure or the author.

Personal favourite: Chapter 13. Introspection-retrospection-Othering-deliberate narrative obfuscation AF.

Along with Sexing the Cherry, this was my favourite, favourite, favourite read for this particular paper's syllabus texts. And you should know that I haven't chanted 'favourite' like a pre-pubescent girl who's just been introduced to the wonders of sanitary napkins with wings since... well, since never. That's just not how I ever rolled. But you get the gist. Fowles, you owe me an entire damn semester's worth of Post-It notes in various shapes and colours and sizes, but goddamn, goddamn, what a read this was. Author's own erudition unquestionable, this has to be one of the first male-written texts that I've read in the longest damn time that I not only didn't want to punch in the face but also fell quite ardently repeat-reading, repeat-analytically in love with. Which is usually rather tough a job for a Lit major, ya feel?

My proposed essay on The French Lieutenant’s Woman: A character sketch of Charles / the anatomy of a Victorian intellectual fuckboi / why men always need to justify the attractiveness of one woman at the expense of another.

Tbd: Narrative style that I thought was A++, the way Fowles creates a seamless amalgamation of multiple thought processes and points of entry. The most apt example of this is the scene where Ernestina is observing herself bashfully in the mirror and there is a comment about '...that odious prinny George the IV' and you halt for a second, perhaps, 'cause you're like, whoaaa there, Ernestina, finally showing some legitnessss. And then you realize it was the narrator-figure making a comment. Not to be confused with the author-figure or the author.

Personal favourite: Chapter 13. Introspection-retrospection-Othering-deliberate narrative obfuscation AF.

Along with Sexing the Cherry, this was my favourite, favourite, favourite read for this particular paper's syllabus texts. And you should know that I haven't chanted 'favourite' like a pre-pubescent girl who's just been introduced to the wonders of sanitary napkins with wings since... well, since never. That's just not how I ever rolled. But you get the gist. Fowles, you owe me an entire damn semester's worth of Post-It notes in various shapes and colours and sizes, but goddamn, goddamn, what a read this was. Author's own erudition unquestionable, this has to be one of the first male-written texts that I've read in the longest damn time that I not only didn't want to punch in the face but also fell quite ardently repeat-reading, repeat-analytically in love with. Which is usually rather tough a job for a Lit major, ya feel?

Maybe when I grow older and read this again I will understand and connect to it more. This book is really different than the ones I usually read, it's quite difficult to pick up on characters feelings and understand the situations they're going through. Quite a nice journey through Victorian times and their understanding and meaning of life, love and other life perspectives.