You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

I had a difficult time with this book. Reading this while quarantined during a pandemic might not have been the best choice. I kept asking myself if it was the book itself, or if it was the fact that I feel like I'm living through a doomsday scenario already. There were actual moments where I would put the book down and struggle with the similarities between the book and of the horror of the present day.

That said, I think upon finishing it that no, I just didn't really like this book. Here's why.

The story is set in a future US, between the years of 2075 and 2095 mostly. And in this future, a few Southern states are at war with the north because they want to continue to use fossil fuels after it has been banned. For me, this might be one of the biggest problems with the whole book.

This novel is filled with brutal violence, torture and massacres, and it simply does not seem believable that it could occur over fossil fuels. I just cannot buy into a world where people would allow for that much brutality over something that they are not directly profiting from. In this book, the South is reduced to a pile of cliches, mostly of people fighting for no reason other than just a hatred of the North. They are mostly fighting amongst themselves unable to agree between all the rebel factions.

I suppose that could be possible, since it does happen, but I think it would need to be maybe 200 hundred years in the future, not 50. In the direction our country is going, it would be very difficult to imagine that people would care enough about gasoline to wipe out entire cities. (Again, when the people defending it are poor and not in anyway retaining direct ownership of the oil fields, why would they care at all?)

But this is just one of numerous frustrating unexplained holes in the plot. Why a huge swath of the west now owned by Mexico, for one. Not only is it not explained, it doesn't have a bit of relevance to anything. There are potentially interesting plot lines such as the new Empire of Bouazizi - created after many revolts similar to the Arab Spring, but this new empire is only alluded to, and again, never really explained. I would have loved to have learned more about it, or have a parallel plot going there. Also, the narrator is writing from a place called New Anchorage. What happened to the old Anchorage? Where is New Anchorage? Apparently we don't need to know.

Finally, the lack of female characters is just repulsive. The main character is female, sort-of. She's some sort of giant (6'5'' at the end, but several mentions of her "still growing") the only dark-skinned person in the entire book (including even her family), and despite being a woman, she's described as very masculine. Several times throughout the book she's referred to as more man then any of the men fighting the war. Of course she's also gay, but that's a total throwaway scene that's out of left-field and never mentioned again.

Are there any female fighters, soldiers, generals, leaders, any women anywhere in this book that are taking up any sort of cause? Nope. There are a couple of women that are staying home and tending children or gardens. The descriptions of women could have come straight from the first civil war and you'd not be able to tell the difference.

I could go on about that, but I'll just say the final glaring disappointment of this book was it's complete lack of imagination when it comes to any aspect of Science Fiction. There is no mention of technology at all, and no explanation for it's absence. There is a little vague reference to "Birds" (drones? planes? who knows) and "Tik-toks" (what I think are solar powered cars - again, not explained) and that's absolutely it. Again, this story could be taking place in 1975 or 1875 and you'd never know the difference.

I wanted to like this book, it had an interesting premise, but it was never fully fleshed out. The writing was dull, and the characters one-dimensional. The whole thing just fell flat for me.

That said, I think upon finishing it that no, I just didn't really like this book. Here's why.

The story is set in a future US, between the years of 2075 and 2095 mostly. And in this future, a few Southern states are at war with the north because they want to continue to use fossil fuels after it has been banned. For me, this might be one of the biggest problems with the whole book.

This novel is filled with brutal violence, torture and massacres, and it simply does not seem believable that it could occur over fossil fuels. I just cannot buy into a world where people would allow for that much brutality over something that they are not directly profiting from. In this book, the South is reduced to a pile of cliches, mostly of people fighting for no reason other than just a hatred of the North. They are mostly fighting amongst themselves unable to agree between all the rebel factions.

I suppose that could be possible, since it does happen, but I think it would need to be maybe 200 hundred years in the future, not 50. In the direction our country is going, it would be very difficult to imagine that people would care enough about gasoline to wipe out entire cities. (Again, when the people defending it are poor and not in anyway retaining direct ownership of the oil fields, why would they care at all?)

But this is just one of numerous frustrating unexplained holes in the plot. Why a huge swath of the west now owned by Mexico, for one. Not only is it not explained, it doesn't have a bit of relevance to anything. There are potentially interesting plot lines such as the new Empire of Bouazizi - created after many revolts similar to the Arab Spring, but this new empire is only alluded to, and again, never really explained. I would have loved to have learned more about it, or have a parallel plot going there. Also, the narrator is writing from a place called New Anchorage. What happened to the old Anchorage? Where is New Anchorage? Apparently we don't need to know.

Finally, the lack of female characters is just repulsive. The main character is female, sort-of. She's some sort of giant (6'5'' at the end, but several mentions of her "still growing") the only dark-skinned person in the entire book (including even her family), and despite being a woman, she's described as very masculine. Several times throughout the book she's referred to as more man then any of the men fighting the war. Of course she's also gay, but that's a total throwaway scene that's out of left-field and never mentioned again.

Are there any female fighters, soldiers, generals, leaders, any women anywhere in this book that are taking up any sort of cause? Nope. There are a couple of women that are staying home and tending children or gardens. The descriptions of women could have come straight from the first civil war and you'd not be able to tell the difference.

I could go on about that, but I'll just say the final glaring disappointment of this book was it's complete lack of imagination when it comes to any aspect of Science Fiction. There is no mention of technology at all, and no explanation for it's absence. There is a little vague reference to "Birds" (drones? planes? who knows) and "Tik-toks" (what I think are solar powered cars - again, not explained) and that's absolutely it. Again, this story could be taking place in 1975 or 1875 and you'd never know the difference.

I wanted to like this book, it had an interesting premise, but it was never fully fleshed out. The writing was dull, and the characters one-dimensional. The whole thing just fell flat for me.

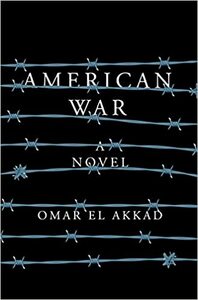

Akkad's novel imagines a second Civil War in the United States. The old hatreds still stew in the distant future. Now, global warming pushes the United States into a second conflict. Water has flooded the coastal cities and seeks to claim more land. Meanwhile, the Federal Government restricts all use of fossil fuels to deal with the emergency. Except the South won't comply. War ensues, but instead of a decisive war, it becomes a stalemate. New technologies developed make the damage done just as devastating as the last Civil War. It's an endless war where America's fortunes are reversed. Instead of being the empire intervening in other countries, they are brought to their knees by their own strife. A strife that is far more devastating.

Akkad easily combines warfare that is going on around the world and placing it square in the United States. One can easily make comparisons to conflicts in the Middle East, particularly with the Israel and Palestine conflict. As we sit in the United States and read about drones in the news (or in books like The Drone Eats with Me) there is nothing more terrifying than seeing this technology used in the United States. It is a startling point to be made by Akkad that war is a universal language. Without seeking peace, there is no end to the pain of war. No one wins.

NOTES FROM

American War

Omar El Akkad

May 7, 2017

Chapter Nine

And what she understood—what none of the ones who came to touch Simon’s forehead understood—was that the misery of war represented the world’s only truly universal language. Its native speakers occupied different ends of the world, and the prayers they recited were not the same and the empty superstitions to which they clung so dearly were not the same—and yet they were. War broke them the same way, made them scared and angry and vengeful the same way. In times of peace and good fortune they were nothing alike but stripped of these things they were kin. The universal slogan of war, she’d learned, was simple: If it had been you, you’d have done no different.

May 8, 2017

Chapter Nine

She soon learned that to survive atrocity is to be made an honorary consul to a republic of pain. There existed unspoken protocols governing how she was expected to suffer. Total breakdown, a failure to grieve graciously, was a violation of those rules. But so was the absence of suffering, so was outright forgiveness. What she and others like her were allowed was a kind of passive bereavement, the right to pose for newspaper photographs holding framed pictures of their dead relatives in their hands, the right to march in boisterous but toothless parades, the right to call for an end to bloodshed as though bloodshed were some pest or vagrant who could be evicted or run out of town. As long as she adhered to those rules, moved within those margins, she remained worthy of grand, public sympathy.

May 8, 2017

Chapter Nine

Rage wrapped itself around her like a tourniquet, keeping her alive even as it condemned a part of her to atrophy.

May 8, 2017

Chapter Thirteen

Many years later, when her letter led me to the place of her buried memories and I read the pages she left behind, I learned all about the moments that filled in the blanks between those things I’d witnessed with my own eyes. And by the time I was done reading, I’d learned every last secret my aunt had to give. Some people are born sentenced to terrible inheritance, diseases that lay dormant in the blood from birth. My sentence was to know, to understand.

May 8, 2017

Chapter Fifteen

There’s this passage in one of the books Albert Gaines once gave me. It said in the South there is no future, only three kinds of past—the distant past of heritage, the near past of experience, and the past-in-waiting. What they’ve got up there in the Blue—what your wife wants, what our parents wanted—is a future.”

May 9, 2017

Chapter Sixteen

Why?” she echoed, bemused. “Because it was the right thing to do.” She chuckled. “Sarat told me you were a sweet boy. Benjamin, but you must understand that in this part of the world, right and wrong ain’t about who wins, or who kills who. In this part of the world, right and wrong ain’t even about right and wrong. It’s about what you do for your own.”

All Excerpts From

Omar El Akkad. “American War.” Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017-04-04. iBooks.

This material may be protected by copyright.

Przez dużą część książki miałem wrażenie, że głównym jej celem jest pokazanie Amerykanom pokazać co robią/zrobili na Bliskim Wschodzie, pisząc o obozach uchodźców, torturach i nikomu niepotrzebnej wojnie dziejących się u nich (Amerykanów) na miejscu. Książka - przeraźliwie smutna - jest niestety dość nudna i tylko ostatnie rozdziały ją jakoś ratują. Nie bardzo wiem jak się dostała do finału nagrody Clarke'a.

Louisiana, April 2075. The Second American War is raging. Sarat Chestnut is too young to fully understand what is going on, but even at her age she understands that times are hard: half of the state is underwater, food is scarce and they are not free to move. Nevertheless, her father wants to go north, where climate is less challenging and where his family can have a future. Another attack kills this dream and Sarat has to flee with her mother, her twin sister and her elder brother to a refugee camp. In Camp Patience, some kind of normal life can be established and from just a weeks of survival become years. People organise themselves according to the new circumstances, however, the chances of enduring peace are small. And, with the time, the danger of another fierce attack grows and Sarat, now a teenager, is in a different position from when her father was killed. She has to witness the worst human behaviour imaginable and this leaves a mark on her. She is not the same person anymore and she will seek revenge for what has been done to her, her family, her people.

Set at some point in the future, Omar El Akkad’s novel is nonetheless easy to imagine. The challenges due to climate change are not that fancy that you could not easily believe them. Since mankind is more prone to securing comfort than thinking ahead for future generations, having vast spaces of land destroyed will definitely be a reality sooner or later. That this – or something completely different – might lead to a civil war even in the United States, is not that inconceivable, either. We have seen many states crumble and fall in the last few years. We can only hope that the novel is much closer to fiction than to reality.

The most striking aspect is of course the protagonist Sarat. We first meet her as a young girl, naive and unaware of most of what happens around her. She is guided by her mother who already shows how powerful women of that family can be. The older she becomes, the stronger she gets. As a teenager, we have a courageous girl who is not only unafraid, but also clever and eager to understand what is going on. This not only saves her life but also makes her the woman she will be later. What she has to witness and go through, strengthens her conviction. As a grown-up woman, especially when she is in prison, we meet an unfaltering and determined woman who cannot be destroyed. Yet, she remains human, she has not completely lost faith in mankind and still can do some good – in her very own understanding.

The experience of war and human beings losing all social behaviour and sympathy for others is what determines the characters’ actions. Sarat realised that

“the misery of war represented the world’s truly universal language” (Pos. 2985) and “The universal slogan of war, she’d learned, was simple: If it had been you, you’d have done no different.”

This dystopian view of the world is the only lesson we can learn from watching the news. In accepting the wars around us, we produce generations who are branded by the experiences and thus ready to do harm in the same way. We should not need novels to illustrate this simple calculation.

Set at some point in the future, Omar El Akkad’s novel is nonetheless easy to imagine. The challenges due to climate change are not that fancy that you could not easily believe them. Since mankind is more prone to securing comfort than thinking ahead for future generations, having vast spaces of land destroyed will definitely be a reality sooner or later. That this – or something completely different – might lead to a civil war even in the United States, is not that inconceivable, either. We have seen many states crumble and fall in the last few years. We can only hope that the novel is much closer to fiction than to reality.

The most striking aspect is of course the protagonist Sarat. We first meet her as a young girl, naive and unaware of most of what happens around her. She is guided by her mother who already shows how powerful women of that family can be. The older she becomes, the stronger she gets. As a teenager, we have a courageous girl who is not only unafraid, but also clever and eager to understand what is going on. This not only saves her life but also makes her the woman she will be later. What she has to witness and go through, strengthens her conviction. As a grown-up woman, especially when she is in prison, we meet an unfaltering and determined woman who cannot be destroyed. Yet, she remains human, she has not completely lost faith in mankind and still can do some good – in her very own understanding.

The experience of war and human beings losing all social behaviour and sympathy for others is what determines the characters’ actions. Sarat realised that

“the misery of war represented the world’s truly universal language” (Pos. 2985) and “The universal slogan of war, she’d learned, was simple: If it had been you, you’d have done no different.”

This dystopian view of the world is the only lesson we can learn from watching the news. In accepting the wars around us, we produce generations who are branded by the experiences and thus ready to do harm in the same way. We should not need novels to illustrate this simple calculation.

I wanted so badly to like this book. I suppose at this point that I’ve read enough near-future dystopian fiction that it takes something special to convince me that the future an author lays out is really plausible. The author’s vision here isn’t necessarily a bridge too far, but the timeline is. The most unrealistic thing about this novel, though - what really killed it for me - was its lack of engagement with race. Ethnicity is mentioned, as are appearances, and certain things one can infer from surnames. Yet the characters seem to be living in a “post-racial” world...fifty years from now.

Three stars because the last quarter of the book was well done, and the author paints a vivid and realistic picture of the making of a terrorist.

Three stars because the last quarter of the book was well done, and the author paints a vivid and realistic picture of the making of a terrorist.

The concept of part of the south seceding again from the US is not that far-fetched in this age of stark separation of multiple sides.

I did find it hard to believe that our modern reliance on social media did not survive in some online format.

Did anyone else notice the historical allusion of the Chestnut family to Mary Chestnut of Civil War diary fame? Of course, Mary's writings survived while Sarat's did not.

Wouldn't surprise me if something like this came to pass.

I did find it hard to believe that our modern reliance on social media did not survive in some online format.

Did anyone else notice the historical allusion of the Chestnut family to Mary Chestnut of Civil War diary fame? Of course, Mary's writings survived while Sarat's did not.

Wouldn't surprise me if something like this came to pass.

I wanted to enjoy this book. I tried to enjoy it, but I found the plot holes and antiquated stereotypes too hard to overcome.

challenging

dark

emotional

sad

tense

medium-paced

dark

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

If you are looking for a super cool, dystopian novel that covers the repetition of American history while adding in futuristic elements of real life calamity and how that might look, this book is not for you.

If you are looking for a long story about the pointlessness of war, the gray area between right and wrong, what war can do to the psyche and how the decisions of those high up impact the individual... well than, this book is for you.

Sarat is a complex and interesting character, I just didn't enjoy the story. The best parts were getting to witness the growing relationship between her and Benjamin. It was also too long. He is a great writer though...

If you are looking for a long story about the pointlessness of war, the gray area between right and wrong, what war can do to the psyche and how the decisions of those high up impact the individual... well than, this book is for you.

Sarat is a complex and interesting character, I just didn't enjoy the story. The best parts were getting to witness the growing relationship between her and Benjamin. It was also too long. He is a great writer though...