Take a photo of a barcode or cover

"There must always be the confidence that the effect of truthfulness can be realized in the mind of the oppressor as well as the oppressed." pg. 60

"Sincerity in human relations is equal to, and the same as, sincerity to God. " pg.62

"... hatred often begins in a situation in which there is contact without fellowship. " pg.65

So much to turn over and consider and reflect upon. From my understanding, these words of Thurman's were among those which inspired the leadership and life of Martin Luther King Jr. The faith of both, their desire to live a life of peace, love and forgiveness toward those who hated them is of the utmost inspiration and conviction.

"Sincerity in human relations is equal to, and the same as, sincerity to God. " pg.62

"... hatred often begins in a situation in which there is contact without fellowship. " pg.65

So much to turn over and consider and reflect upon. From my understanding, these words of Thurman's were among those which inspired the leadership and life of Martin Luther King Jr. The faith of both, their desire to live a life of peace, love and forgiveness toward those who hated them is of the utmost inspiration and conviction.

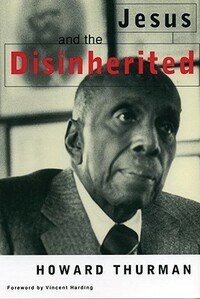

Such beautiful, evergreen knowledge. Written in the 40s and thought to be Dr. Kings inspiration behind the letters from Montgomery jail, it’s heady and important.

Howard Thurman explores the response of the disinherited, man who has their back against the wall through an exploration of Jesus under the culture of his days, how especially the black people of America can respond to the injustice of his day, is still as relevant today. How does the three hounds of hell: fear, deception, and hate lead to the wrong decisions and actions, but only love as attested by Jesus’ love for the enemies can bring true reconciliation and dignity to the disinherited life as the Father’s beloved.

Howard Thurman in his classic Jesus and the Disinherited addresses the challenging affront of how he can claim to be a Christian, while it was Christians who brought Africans over to the Americas and Christians that propagated slavery in the U.S. What significance does “the religion of Jesus” have for those “with their backs against the wall?”

Thurman begins by delving into the historical context of the Jews during the first century. They were in many ways similar to African-Americans in the U.S. particularly before the civil rights movement – a marginalized people living under the power of another group. Further, not only was Jesus part of the unprivileged, being a Jew, but he was also a poor Jew. How should a person respond given such circumstances? Often people assume that they can either resist, like the Zealots, or not resist, like the Pharisees. Yet, Jesus provided another way. Thurman writes that Jesus “recognized... that anyone who permits another to determine the quality of his inner life gives into the hands of the other the keys of his destiny (28).” The religion of Jesus was not what we see in the powerful and oppressive, but rather was “a technique of survival for the oppressed (29).”

This mindset is exemplified through overcoming what Thurman calls the “persistent hounds of hell that dog the footsteps of the poor, the disposed, the disinherited (36).” Fear is constant for those at the margins. Feelings of helplessness lead to a type of fear that the privileged cannot understand. “It is spawned by the perpetual threat of violence everywhere (37).” The religion of Jesus reaffirms one’s identity. Thurman retells a sermon given to black slaves where they triumphantly proclaim, “You-you are not niggers. You-you are not slaves. You are God’s children.” This affirms who they are and grounds their personal dignity where they can absorb some of the fear reaction. Further, it levels the playing field in a sense. “This new orientation” allows for “an objective, detached appraisal of other people, particularly one’s antagonists,” which can “protect one from inaccurate and exaggerated estimates of another person’s significance (52).” Furthermore, the message of Jesus builds a place for hope to blossom and grow even amidst the worst of situations. To know that God cares for you can spur one to purpose and a life without fear.

A second pervasive hound of hell for the poor is the tendency to fight their disadvantages and to protect themselves through working to deceive the strong. Thurman believes that this constant lying and deceiving tarnishes the soul. “If a man continues to call a good thing bad, he will eventually lose his sense of moral distinctions.... A man who lies habitually becomes a lie, and it is increasingly impossible for him to know when he is lying and when he is not (64-65).” How is Jesus relevant to those who (seemingly) must lie, cheat, and deceive in order to survive? Surely we cannot fault them. Acts of survival are amoral; they are simply required. Thurman exposes the folly of this logic. The end goal that propels the poor in these situations is to “not be killed” and “morality takes its meaning from that center (69).” Occasionally this center is swallowed by something larger. Patriotism for instance gives meaning beyond simple survival. Thurman argues that Jesus proclaims to center on living within God’s will. One’s purpose and moral center focuses on being a part of God’s work; therefore, there is no fear of scorn. He writes, “There must always be the confidence that the effect of truthfulness can be realized in the mind of the oppressor as well as the oppressed (70).” Such a profound challenge calls the disinherited to “an unwavering sincerity” that is honest, true, unhypocritical, and life-giving.

Thurman deals with the third hound of hell – hate – by describing the process. It “often begins”... with “contact without fellowship (75),” cordiality without genuine feelings of warmth. These situations lead to relationships lacking any sort of sympathy. He writes, “I can sympathize only when I see myself in another’s place (77).” And is this type of unsympathetic attitude that undergirds most relationships between the weak and the strong. Third, “unsympathetic understanding tends to express itself in the active functioning of ill will (77),” which leads finally to full-embodied hatred for another. Hatred is born in the mind of the oppressed through great bitterness. It can become “a source of validation for [one’s] personality (80)” by giving a sense of significance in defiance to those you hate. Similarly to deception above, Thurman believes that “hatred destroys finally the core of the life of the hater (86).” It “is death to the spirit and disintegration of ethical and moral values (88).” Thurman concludes simply that “Jesus rejected hatred.” It runs contrary to creativity of the mind, vitality of the spirit, and squelches any sort of connection to God.

The final chapter explores the central ethic of Jesus’ message: love, and in particular love of enemy. According to Thurman, Jesus exemplified three types of enemy love. The first is to love those in your community who have become enemies. For Jesus these included the household of Israel, your personal enemies. Second, Jesus proclaimed love that stretched even to tax-collectors. These people were also sons and daughters of Abraham. But further than that – Jesus called his disciples to love even the Romans, those who marginalized and oppressed the Jewish people. This means “to recognize some deep respect and reverence for their persons (94).” Love is what frees everyone to see the other as human like themselves; it is what brings forgiveness and allows the disinherited to experience full life.

Howard Thurman’s understanding and description of Jesus was both enlightening and convicting. He brings deeply personal insight to the plight of the marginalized. Although written for African-Americans in the late 1940s, Jesus and the Disinherited applies to people today by giving hope for the disinherited and forcing empathy on the privileged.

Thurman begins by delving into the historical context of the Jews during the first century. They were in many ways similar to African-Americans in the U.S. particularly before the civil rights movement – a marginalized people living under the power of another group. Further, not only was Jesus part of the unprivileged, being a Jew, but he was also a poor Jew. How should a person respond given such circumstances? Often people assume that they can either resist, like the Zealots, or not resist, like the Pharisees. Yet, Jesus provided another way. Thurman writes that Jesus “recognized... that anyone who permits another to determine the quality of his inner life gives into the hands of the other the keys of his destiny (28).” The religion of Jesus was not what we see in the powerful and oppressive, but rather was “a technique of survival for the oppressed (29).”

This mindset is exemplified through overcoming what Thurman calls the “persistent hounds of hell that dog the footsteps of the poor, the disposed, the disinherited (36).” Fear is constant for those at the margins. Feelings of helplessness lead to a type of fear that the privileged cannot understand. “It is spawned by the perpetual threat of violence everywhere (37).” The religion of Jesus reaffirms one’s identity. Thurman retells a sermon given to black slaves where they triumphantly proclaim, “You-you are not niggers. You-you are not slaves. You are God’s children.” This affirms who they are and grounds their personal dignity where they can absorb some of the fear reaction. Further, it levels the playing field in a sense. “This new orientation” allows for “an objective, detached appraisal of other people, particularly one’s antagonists,” which can “protect one from inaccurate and exaggerated estimates of another person’s significance (52).” Furthermore, the message of Jesus builds a place for hope to blossom and grow even amidst the worst of situations. To know that God cares for you can spur one to purpose and a life without fear.

A second pervasive hound of hell for the poor is the tendency to fight their disadvantages and to protect themselves through working to deceive the strong. Thurman believes that this constant lying and deceiving tarnishes the soul. “If a man continues to call a good thing bad, he will eventually lose his sense of moral distinctions.... A man who lies habitually becomes a lie, and it is increasingly impossible for him to know when he is lying and when he is not (64-65).” How is Jesus relevant to those who (seemingly) must lie, cheat, and deceive in order to survive? Surely we cannot fault them. Acts of survival are amoral; they are simply required. Thurman exposes the folly of this logic. The end goal that propels the poor in these situations is to “not be killed” and “morality takes its meaning from that center (69).” Occasionally this center is swallowed by something larger. Patriotism for instance gives meaning beyond simple survival. Thurman argues that Jesus proclaims to center on living within God’s will. One’s purpose and moral center focuses on being a part of God’s work; therefore, there is no fear of scorn. He writes, “There must always be the confidence that the effect of truthfulness can be realized in the mind of the oppressor as well as the oppressed (70).” Such a profound challenge calls the disinherited to “an unwavering sincerity” that is honest, true, unhypocritical, and life-giving.

Thurman deals with the third hound of hell – hate – by describing the process. It “often begins”... with “contact without fellowship (75),” cordiality without genuine feelings of warmth. These situations lead to relationships lacking any sort of sympathy. He writes, “I can sympathize only when I see myself in another’s place (77).” And is this type of unsympathetic attitude that undergirds most relationships between the weak and the strong. Third, “unsympathetic understanding tends to express itself in the active functioning of ill will (77),” which leads finally to full-embodied hatred for another. Hatred is born in the mind of the oppressed through great bitterness. It can become “a source of validation for [one’s] personality (80)” by giving a sense of significance in defiance to those you hate. Similarly to deception above, Thurman believes that “hatred destroys finally the core of the life of the hater (86).” It “is death to the spirit and disintegration of ethical and moral values (88).” Thurman concludes simply that “Jesus rejected hatred.” It runs contrary to creativity of the mind, vitality of the spirit, and squelches any sort of connection to God.

The final chapter explores the central ethic of Jesus’ message: love, and in particular love of enemy. According to Thurman, Jesus exemplified three types of enemy love. The first is to love those in your community who have become enemies. For Jesus these included the household of Israel, your personal enemies. Second, Jesus proclaimed love that stretched even to tax-collectors. These people were also sons and daughters of Abraham. But further than that – Jesus called his disciples to love even the Romans, those who marginalized and oppressed the Jewish people. This means “to recognize some deep respect and reverence for their persons (94).” Love is what frees everyone to see the other as human like themselves; it is what brings forgiveness and allows the disinherited to experience full life.

Howard Thurman’s understanding and description of Jesus was both enlightening and convicting. He brings deeply personal insight to the plight of the marginalized. Although written for African-Americans in the late 1940s, Jesus and the Disinherited applies to people today by giving hope for the disinherited and forcing empathy on the privileged.

challenging

emotional

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

challenging

hopeful

reflective

medium-paced

This is a wise and important book. In depth analysis of humankind - our heart, soul, community. Just read it. You won't be sorry.