Take a photo of a barcode or cover

emotional

reflective

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

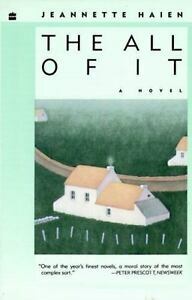

This is a quiet, slim novel about a woman named Enda telling a priest the story of her life after her husband dies -- and she is compelled to reveal a secret that they have kept for fifty years.

The book is as much about the reactions of young Father Declan as it is about Enda's story.

I quickly guessed the secret, but that did not make the story any less worth reading.

The book is as much about the reactions of young Father Declan as it is about Enda's story.

I quickly guessed the secret, but that did not make the story any less worth reading.

A beautiful, simple, little story. Best if you are a fan of Irish stories because so much is untold as in nearly any other Irish literature.

emotional

reflective

sad

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

"...A moral story of the most complex sort." So much to think about from this little book.

This little treasure of a book fell into my lap and I am so grateful! The story is simple, but really far from it. Father Declan hears the deathbed confession of Kevin and learns that he and his wife Enda have been living together in this small Irish village for fifty years, without the sacrament of marriage. Shocking at the time, Father then learns there is more to the story when Enda wants to talk to him, not as a priest, but as a friend. The language of the story is a pure joy to read. The author was a pianist before writing this first novel later in life. The words flow like music. The imagery, especially as Father works through his thoughts in a salmon stream, is splendid. Such a lovely book to read!

PAINTING: The Confession, 1838, by Giuseppe Molteni

I took up this book on Louise Erdrich's recommendation (from her afterword in The Sentence, which lists SO MANY books I hope to read).

We begin with a priest daring nature, as he reels for a salmon on a terribly rainy, windswept day, the river a roiling turbulence, on the very last day of the fishing season. Every angler knows the fish are hidden deeply away and there'll be no catching anything, but the priest doggedly pursues his fate, arms aching, body drenched through. He is at war.

This is a quiet story, a contemplative tale of Ireland: we turn back a while, to a parishioner who is dying, and this fisherman priest persuades him to make a final confession before giving him last rites, as the man has indicated there's something to tell about himself and his wife. Kevin insists on telling so the priest won't bother Enda. Just as he's about to begin, however, his eyes glaze, he loses speech and soon thereafter, Kevin dies. The priest is all sorts of Irish supercilious priesthood (a trait sadly not limited to Irish priests) and demands the story from Enda, since both parties were somehow engaged in sin. And he demands she tell him in the confessional. She refuses. If he wants the story, he'll have to listen to it with Kevin lying in his bed, ready for internment:

"'I appreciate, Enda, that it’ll be no easier for you to tell than for me to hear.” Her brow cleared. She said, “Thank you, Father.” She stood up. “I’ve water boiling. I’ll just give us some tea.... Take a chair for yourself.” Still, though, she hesitated. “You’ll need to be patient, Father,” she qualified. “I will of course, Enda.” “—not stop me over the first thing I tell you—” “I won’t.” “—hear me through to the end, I mean.” She turned from him towards the bed and stood for what seemed to him to be an immense length of time, her back to him as she looked at Kevin’s face. In his chair, he waited, feeling large and uncollared. He shifted his feet. His shoes made a soft, scurring sound on the floor. She shuddered. As long as it would be granted him to live, he would remember how, then, her spine straightened as she filled her lungs with a diver’s deep breath, and how, just before she plunged into the violent waters of her telling, she turned back to him, her eyes glistening and entreating and charged with courage, and, finally... the sped words fell."

"'There’s no way to get it across to you”—she spoke through her teeth—“the fear we had of our dad.” “Ah, I see. Forgive me, Enda. But I see now—” “You have to see,” she said deeply. “If you’re to understand, you have to.” “I do. I see now. Believe me, Enda.” “So, I’ll go on then?” “Please, Enda.'”

"He urged, “Don’t dwell on it, Enda; it’ll do no good.” Then, foolishly, because she remained so pitched: “I can imagine how terrible it must have been.” She started: “No, you can’t,” she said abruptly, though not unkindly. “It’s something that can’t be imagined.'"

They had had to run away together after being locked in a stone room, in January, without even sweaters, and no food or water for two days. They were only 15 and 14, then.

"Kevin’d made up his mind that we should go together to the gate-keeper’s lodge and see if there might be work for us as a pair. If it proved out for us, he said, it’d give us a chance to catch our breath. But before we went to ask, he took off for Ballymote town and bought a curtain ring for my finger, had the part you put the thread through filed off so it’d look like a wedding ring. You can see—” She held out her left hand with the eagernesof a child showing off a treasure. “I’ve never had it off...'"

She tells him how they'd found this house and farmstead, 48 years ago, what a ruiin it was, and how she imagined it could be:

"'That image, Father, I’d had of the blue tea-cloth spread on a table? Well, you’ll not believe it, but for me, it was there.... It, and a lit fire. Not the rubble and mess, but order, the truth, you know, of the way it could be.” She spoke the last words deeply, like a proven sibyl. He nodded vigorously. Truly, she was marvellous [sic]. “Keep on,” he urged."

Clearly, along the way the priest falls in love. But then, perhaps overcome with jealousy, envy, or both, he accuses her of living in sin. And she, in turn, absolutely blasts him for it, until he realizes what a total asshat he's been. Still, she doesn't dismiss him outright but holds out the possibility of forgiveness. At Kevin's funeral, she lets him drive her home.

Later, in the last moments of that tempestuous day as he battled himself, his god, and nature itself, he manages with shivering muscles and the help of a ghillie (a hired hand to assist rods, or fishermen) and a net, to wrestle in a salmon weighing almost 25 pounds. He drives immediately to Enda, triumphant and renewed. She delicately reminds him of their respective positions while acknowledging their need for each other as friends, and sets them on track to continue as widow and parish priest, safe from any harm they might otherwise attempt. His catch appears in The Irish Times some days later--and the bishop invites himself to dinner, writing: "I'll bring the wine."

Enda is MAGNIFICENT, in every possible way. I enjoyed this little story a great deal.

Short and sweet but not all that memorable for me. I think I might be immune to the sweet and subtle stories after wallowing in so much murder and mayhem. A nice pallet cleanser, but I guess I kinda prefer a bit more drama and action. For now anyway.