Take a photo of a barcode or cover

This is the largely untold story of the holocaust. The Jewish survivors were literate and encouraged to write about their experiences of the shoah for future generations. The gypsy survivors were often illiterate and less encouraged to recount their histories. It is not clear how many gypsies were killed as part of the Nazi's final solution, but their suffering was on a par with that of the Jews. I visited Auschwitz shortly after reading this and the guide took us past the notorious block 13, where the gypsies were housed, not wanting to tell us of what happened to the Roma and Sinto, preferring just to dwell on the Jewish and Polish victims. This is a story that needs to be heard.

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

sad

tense

fast-paced

Wow, i finally found a true recount of what happened to the persecuted gypsy (sinti and roma) people during world War II. Otto lived a very interesting life and at such an young age it was for ever changed. this book taught me a lot that I didn't know. it also showed me how passionate Otto was after the war with sharing his story and making sure it was marked down with details only a witness of this horrible time would know. I hope Otto is resting in peace with his family. thankyou for sharing your story.

challenging

dark

emotional

medium-paced

4.5. An amazing and very well-written true story.

I’ve read a few Auschwitz books now, this one is more straight to the fact it doesn’t dramatize the life inside of the camp in the way that some of the other books do. Which makes it a very different read, but possibly more insightful, and better in many ways..

there’s no moment with you, forget that this really happened

there’s no moment with you, forget that this really happened

This is a very easy-to-read (in terms of language, presentation and flow, if not subject matter) book that explores an aspect of the Nazi genocides that Europe probably doesn't talk enough about – the genocide of the Sinti and Roma.

We follow a boy from childhood as the Nazi persecution begins and his family are forcibly relocated, through into adolescence as he is sent between several work and concentration camps, and following the liberation of the camps as he tries to build himself an adult life.

What is striking, and makes it such a powerful book, is the matter-of-factness with which the story is recounted (it's been dictated from father to child) and how quickly the appalling conditions and pervasiveness of death become routine.

We follow a boy from childhood as the Nazi persecution begins and his family are forcibly relocated, through into adolescence as he is sent between several work and concentration camps, and following the liberation of the camps as he tries to build himself an adult life.

What is striking, and makes it such a powerful book, is the matter-of-factness with which the story is recounted (it's been dictated from father to child) and how quickly the appalling conditions and pervasiveness of death become routine.

I, Otto Rose, saw it with my own eyes, and live to tell the tale.

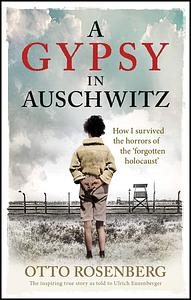

In this heartbreaking and riveting memoir, holocaust survivor and activist Otto Rosenberg describes his Sinti childhood in Berlin, the concentration camps and the post-war treatment of his people.

The Sinti are a subgroup of the Romani people, an Indo-Aryan ethnic group often referred to with the pejorative term "Gypsy." As the title of this book suggests, the mass killing of the Sinti and the Roma is often described as a 'forgotten holocaust.' Indeed, many narratives ignore the racial aspects of their persecution and blame the victims for being members of an 'asocial group.' A Gypsy in Auschwitz is a testimony of what the Sinti and Roma people experienced and how the world looked the other way, before, during and after the war.

In the first chapters, Otto provides vivid descriptions of his schooling, his Catholic faith and everyday life in his community. It is a precious snapshot of pre-war Sinti life. Otto and his grandmother lived, studied and worked in Berlin where "Lots of Sinti people moved around constantly in their caravans, but my grandmother wasn’t keen on that sort of life." Increasingly difficult situations will only strengthen the incredible bond between Otto and his grandmother. His grandmother exudes goodness, serving as a sort of guardian angel to local children. As restrictions against his people increase, they're forced to stop their usual trades, given compulsory labour and receive welfare payments instead. Orders directed at the Jewish community then are also applied to Sinti and Roma, and therefore a subsequent ban on their employment leads to accusations that they are unwilling to work.

During this time, Otto experiences further discrimination and poor treatment, with his classmates explicitly targeting him due to his darker skin. His family is relocated to a camp (a hastily set up shanty town) for Roma people which lacks access to clean water and is surrounded by sewage. Still able to go out, the boy is asked by a woman at the bakery, "What can I do for you today, my love? Did you forget to wash your face again?" Throughout Otto's life, society will place him into situations where he is unable to work or clean himself, and then make hurtful remarks that he is a "dirty Gypsy." Readers unfamiliar with Sinti or Roma culture might miss the references to hygiene laws such as "You can imagine the smell. Left to our own devices, we would never have pitched up in such a spot, not least because our laws forbid it." Forcing these communities to break cultural laws for the placement of rubbish and washing adds an additional layer of humiliation to their treatment. Ethnic Germans come to sightsee in the camp, as "The camp caused a great deal of curiosity: lots of people would come and take photos, and on a few occasions, they sneaked into the camp itself."

His family attracts the attentions of Nazi psychologist Robert Ritter and his assistant, the anthropologist and nurse Eva Justin. The reader, knowing what medical experimentation is to come, comprehends an undercurrent of horror. "I'd like Otto to come by the Institute of Anthropology after school" Justin says, and Otto, being a good schoolboy, visits and does her psychological tests and sleeps in her house. It's like something from Grimms' Fairy Tales, with this monstrous woman offering a food, drinks and a "heavenly bed." Otto is still free to go in and out of his camp, but he will struggle to explain the actions of the adults in his life. "It would have been better if she had given me a beating; I could have processed it a whole lot better."

Throughout the text, Otto reflects on lost opportunities and his interrupted youth. He shares happy memories of his first holy communion and the wonderful food his teachers shared with him. "The food was so delicious, and after school or for supper there was always a sweet, scrumptious soup served in a big mug, with baked or fried dumplings to go with it. When I cast my mind back, I can still conjure up the taste, even though I’ve never had such things since. The food alone was enough to keep us going back time and time again." This Sinti boy, who most would incorrectly assume has no interest in education, delights in learning Latin, serves as an altar boy and dreams of being a priest. "Of course, I have these wonderful memories of them, but it does also have to be said that the Catholic and Protestant churches both turned over their registers to the Nazis, so ultimately they contributed towards the persecution of the Sinti and Roma." Otto is eager to please the adults in his life. Later he will reflect that "If things had gone on the way they were, without the war, I might well have stayed at Christ the King and I think that I might even have become a priest. But, of course, we’ll never know."

This book is a necessary reminder that no amount of good behaviour, studiousness or military service could make up for having Sinti or Roma blood. "My uncles had all been in the military – cavalry, navy and infantry. One cousin was even in the Luftwaffe. Another had fought in Finland as part of the mountain troops...My uncle said, ‘I’m not fighting for a country that does this.’ So they confiscated his gun, and 14 days later he ended up in Auschwitz, too."

Otto's tales of endurance from the camps catalogue the horrors, ranging from the lice ("If you shook a blanket, they would scatter everywhere like grains of sand. The place was teeming with them.") to the deaths. He sensitively describes those who clearly lost their minds and how emotionally shattered everyone was from being constantly surrounded by violence and death. The treatment of children and their bodies is incredibly hard to read. There are also disturbing reminders of how many seemingly good people witnessed these events unfolding. For example, "Once the train had been going for a while, the children began to ask the Red Cross sister who was accompanying them why I was locked up." Nobody seems to question why a train full of Roma and Sinti children are on the train in the first place. He also considers the difficulties of having so many people of different nationalities and languages crammed in together. These sections show that the Roma people are not a monolithic group. Additionally, it is interesting to read his thoughts on why some people were able to endure more hardship than others.

This book sensitively describes the suffering of women, particularly in the loss of their fertility from forced sterilisation and their repeated sexual assaults by the SS. "The SS abused our women. Not in the block itself, but usually behind it or elsewhere. Afterwards, they shot them. One of my own relatives was shot in the head, but the bullet passed right through. She’s still alive, but she’s barely there at times, and she can’t bear to be reminded of what she went through back then." He shares with empathy how the loss of their ability to have their own children will create further problems after the war. Forced sterilization will haunt these survivors' lives as they try to move forward by marrying and having children of their own.

This memoir does not package his concentration camp experience as a source of inspiration or tribute to the undefeatable human spirit. Throughout the book he tries to understand how such senseless violence and hatred from his fellow Germans emerged, especially those who had once treated him kindly. As the war progresses, an act of kindness was "as though the sun had suddenly burst out from behind a cloud. The sheer joy of it – knowing that there were still good people in the world." Still, he develops an understandable fear of strangers and the unknown. After his release, he is terrified of the arriving Americans, British and Russians as he is the Germans. Outside the camp, he is malnourished, with no place to go and a heart full of rage. Where are his family members? How should he live?

Young Otto attempts to process all that has happened to him, his family and his country. If you know how Roma and Sinti are still treated today, these often uncomfortable accounts of how they were turned away from aid will sound depressingly familiar. Families who were well and whole before the war were left broken, economically and spiritually. They run into their abusers unpunished in the street and find themselves placed into the same work they were doing in the concentration camps. When Otto tries to refuse doing that same work, his superiors say he can't refuse to work and that he has to contribute. "That was how fast they came down on us again and insisted that we slave away. They were the same old Nazis in the same old jobs." They demanded that the concentration camp survivors rebuild the city as if they were responsible for its ruin.

Changing ideas of citizenship is a constant issue for Otto. Despite being born in East Prussia and brought up in Berlin, he is repeatedly congratulated for speaking German well. Occasionally he receives preferential treatment in the camps for being from Berlin. However, when he goes looking for reparations for his time in the concentration camps and the murder of so much of his family, he says "I had to go to the district court, only to be told that I wasn’t a real German and had no ties to Berlin. 'He’s a gypsy. Roving spirit and all that. Berlin’s never been his home.'" Otto finds, like many other Roma and Sinti survivors, that people will say their possessions, businesses and homes could not have been stolen because "Gypsies" couldn't possibly have ever owned anything. When their documents are stolen or destroyed, they can't prove how many family members have been murdered by the state. Nazi anthropologists and scientists collected his genealogy, but after the war they refuse to recognise his relationship with his mother and siblings due to the lack of paperwork. The heartlessness of the bureaucrats he deals with is astonishing, but not surprising. These chapters are key reading for anyone wishing to understand why this community is distrustful of those in authority. This will inspire Otto to be a leader and an activist for those were denied restitution and recognition after the war. Inescapable brutality and sorrow end with callous disregard for the Sinti and Roma victims, and Otto provides a meditation on how these barriers perpetuate disadvantage.

The rage over his experiences nearly consumes him. "When I first arrived there, I was full of hatred and intent on killing. I wanted to murder everyone, not just those who had tormented us in the camp. I thought, ‘You lot never accepted that we were Germans, so when we get out, we’ll kill you Germans in turn." Somehow he is able to redirect that rage and turn it into activism, addressing the "second wave of suffering on the Sinti and the Roma" including seeking the official recognition of their genocide in 1982, their racial prosecution at Berlin-Marzahn Rastplatz in 1987 and having a memorial erected in Berlin in 2012. Throughout this, he defiantly refers to himself as a German. " How the SS and, I suppose, Germans like you or me could have done what they did is beyond me. Nobody can understand it." Otto will leave the camps unable to speak about his experiences and re-enter society as a voice for his people.

This memoir insists the reader understand that the maltreatment of his people did not end in 1945. This testimony includes how he continued to live with his grief and loss, and found his faith after so much was taken from him. He discusses issues related to community, intergenerational trauma and memory with clarity and courage. The afterword by his daughter, Petra Rosenberg, is a brilliant call to action which reinforces the "need for civil rights work by Sinti and Roma groups."

Otto's story deserves the widest possible readership and should be added to the reading list of anyone wishing to learn about Europe's largest minority group.

This book was provided by Octopus Publishing for review.

In this heartbreaking and riveting memoir, holocaust survivor and activist Otto Rosenberg describes his Sinti childhood in Berlin, the concentration camps and the post-war treatment of his people.

The Sinti are a subgroup of the Romani people, an Indo-Aryan ethnic group often referred to with the pejorative term "Gypsy." As the title of this book suggests, the mass killing of the Sinti and the Roma is often described as a 'forgotten holocaust.' Indeed, many narratives ignore the racial aspects of their persecution and blame the victims for being members of an 'asocial group.' A Gypsy in Auschwitz is a testimony of what the Sinti and Roma people experienced and how the world looked the other way, before, during and after the war.

In the first chapters, Otto provides vivid descriptions of his schooling, his Catholic faith and everyday life in his community. It is a precious snapshot of pre-war Sinti life. Otto and his grandmother lived, studied and worked in Berlin where "Lots of Sinti people moved around constantly in their caravans, but my grandmother wasn’t keen on that sort of life." Increasingly difficult situations will only strengthen the incredible bond between Otto and his grandmother. His grandmother exudes goodness, serving as a sort of guardian angel to local children. As restrictions against his people increase, they're forced to stop their usual trades, given compulsory labour and receive welfare payments instead. Orders directed at the Jewish community then are also applied to Sinti and Roma, and therefore a subsequent ban on their employment leads to accusations that they are unwilling to work.

During this time, Otto experiences further discrimination and poor treatment, with his classmates explicitly targeting him due to his darker skin. His family is relocated to a camp (a hastily set up shanty town) for Roma people which lacks access to clean water and is surrounded by sewage. Still able to go out, the boy is asked by a woman at the bakery, "What can I do for you today, my love? Did you forget to wash your face again?" Throughout Otto's life, society will place him into situations where he is unable to work or clean himself, and then make hurtful remarks that he is a "dirty Gypsy." Readers unfamiliar with Sinti or Roma culture might miss the references to hygiene laws such as "You can imagine the smell. Left to our own devices, we would never have pitched up in such a spot, not least because our laws forbid it." Forcing these communities to break cultural laws for the placement of rubbish and washing adds an additional layer of humiliation to their treatment. Ethnic Germans come to sightsee in the camp, as "The camp caused a great deal of curiosity: lots of people would come and take photos, and on a few occasions, they sneaked into the camp itself."

His family attracts the attentions of Nazi psychologist Robert Ritter and his assistant, the anthropologist and nurse Eva Justin. The reader, knowing what medical experimentation is to come, comprehends an undercurrent of horror. "I'd like Otto to come by the Institute of Anthropology after school" Justin says, and Otto, being a good schoolboy, visits and does her psychological tests and sleeps in her house. It's like something from Grimms' Fairy Tales, with this monstrous woman offering a food, drinks and a "heavenly bed." Otto is still free to go in and out of his camp, but he will struggle to explain the actions of the adults in his life. "It would have been better if she had given me a beating; I could have processed it a whole lot better."

Throughout the text, Otto reflects on lost opportunities and his interrupted youth. He shares happy memories of his first holy communion and the wonderful food his teachers shared with him. "The food was so delicious, and after school or for supper there was always a sweet, scrumptious soup served in a big mug, with baked or fried dumplings to go with it. When I cast my mind back, I can still conjure up the taste, even though I’ve never had such things since. The food alone was enough to keep us going back time and time again." This Sinti boy, who most would incorrectly assume has no interest in education, delights in learning Latin, serves as an altar boy and dreams of being a priest. "Of course, I have these wonderful memories of them, but it does also have to be said that the Catholic and Protestant churches both turned over their registers to the Nazis, so ultimately they contributed towards the persecution of the Sinti and Roma." Otto is eager to please the adults in his life. Later he will reflect that "If things had gone on the way they were, without the war, I might well have stayed at Christ the King and I think that I might even have become a priest. But, of course, we’ll never know."

This book is a necessary reminder that no amount of good behaviour, studiousness or military service could make up for having Sinti or Roma blood. "My uncles had all been in the military – cavalry, navy and infantry. One cousin was even in the Luftwaffe. Another had fought in Finland as part of the mountain troops...My uncle said, ‘I’m not fighting for a country that does this.’ So they confiscated his gun, and 14 days later he ended up in Auschwitz, too."

Otto's tales of endurance from the camps catalogue the horrors, ranging from the lice ("If you shook a blanket, they would scatter everywhere like grains of sand. The place was teeming with them.") to the deaths. He sensitively describes those who clearly lost their minds and how emotionally shattered everyone was from being constantly surrounded by violence and death. The treatment of children and their bodies is incredibly hard to read. There are also disturbing reminders of how many seemingly good people witnessed these events unfolding. For example, "Once the train had been going for a while, the children began to ask the Red Cross sister who was accompanying them why I was locked up." Nobody seems to question why a train full of Roma and Sinti children are on the train in the first place. He also considers the difficulties of having so many people of different nationalities and languages crammed in together. These sections show that the Roma people are not a monolithic group. Additionally, it is interesting to read his thoughts on why some people were able to endure more hardship than others.

This book sensitively describes the suffering of women, particularly in the loss of their fertility from forced sterilisation and their repeated sexual assaults by the SS. "The SS abused our women. Not in the block itself, but usually behind it or elsewhere. Afterwards, they shot them. One of my own relatives was shot in the head, but the bullet passed right through. She’s still alive, but she’s barely there at times, and she can’t bear to be reminded of what she went through back then." He shares with empathy how the loss of their ability to have their own children will create further problems after the war. Forced sterilization will haunt these survivors' lives as they try to move forward by marrying and having children of their own.

This memoir does not package his concentration camp experience as a source of inspiration or tribute to the undefeatable human spirit. Throughout the book he tries to understand how such senseless violence and hatred from his fellow Germans emerged, especially those who had once treated him kindly. As the war progresses, an act of kindness was "as though the sun had suddenly burst out from behind a cloud. The sheer joy of it – knowing that there were still good people in the world." Still, he develops an understandable fear of strangers and the unknown. After his release, he is terrified of the arriving Americans, British and Russians as he is the Germans. Outside the camp, he is malnourished, with no place to go and a heart full of rage. Where are his family members? How should he live?

Young Otto attempts to process all that has happened to him, his family and his country. If you know how Roma and Sinti are still treated today, these often uncomfortable accounts of how they were turned away from aid will sound depressingly familiar. Families who were well and whole before the war were left broken, economically and spiritually. They run into their abusers unpunished in the street and find themselves placed into the same work they were doing in the concentration camps. When Otto tries to refuse doing that same work, his superiors say he can't refuse to work and that he has to contribute. "That was how fast they came down on us again and insisted that we slave away. They were the same old Nazis in the same old jobs." They demanded that the concentration camp survivors rebuild the city as if they were responsible for its ruin.

Changing ideas of citizenship is a constant issue for Otto. Despite being born in East Prussia and brought up in Berlin, he is repeatedly congratulated for speaking German well. Occasionally he receives preferential treatment in the camps for being from Berlin. However, when he goes looking for reparations for his time in the concentration camps and the murder of so much of his family, he says "I had to go to the district court, only to be told that I wasn’t a real German and had no ties to Berlin. 'He’s a gypsy. Roving spirit and all that. Berlin’s never been his home.'" Otto finds, like many other Roma and Sinti survivors, that people will say their possessions, businesses and homes could not have been stolen because "Gypsies" couldn't possibly have ever owned anything. When their documents are stolen or destroyed, they can't prove how many family members have been murdered by the state. Nazi anthropologists and scientists collected his genealogy, but after the war they refuse to recognise his relationship with his mother and siblings due to the lack of paperwork. The heartlessness of the bureaucrats he deals with is astonishing, but not surprising. These chapters are key reading for anyone wishing to understand why this community is distrustful of those in authority. This will inspire Otto to be a leader and an activist for those were denied restitution and recognition after the war. Inescapable brutality and sorrow end with callous disregard for the Sinti and Roma victims, and Otto provides a meditation on how these barriers perpetuate disadvantage.

The rage over his experiences nearly consumes him. "When I first arrived there, I was full of hatred and intent on killing. I wanted to murder everyone, not just those who had tormented us in the camp. I thought, ‘You lot never accepted that we were Germans, so when we get out, we’ll kill you Germans in turn." Somehow he is able to redirect that rage and turn it into activism, addressing the "second wave of suffering on the Sinti and the Roma" including seeking the official recognition of their genocide in 1982, their racial prosecution at Berlin-Marzahn Rastplatz in 1987 and having a memorial erected in Berlin in 2012. Throughout this, he defiantly refers to himself as a German. " How the SS and, I suppose, Germans like you or me could have done what they did is beyond me. Nobody can understand it." Otto will leave the camps unable to speak about his experiences and re-enter society as a voice for his people.

This memoir insists the reader understand that the maltreatment of his people did not end in 1945. This testimony includes how he continued to live with his grief and loss, and found his faith after so much was taken from him. He discusses issues related to community, intergenerational trauma and memory with clarity and courage. The afterword by his daughter, Petra Rosenberg, is a brilliant call to action which reinforces the "need for civil rights work by Sinti and Roma groups."

Otto's story deserves the widest possible readership and should be added to the reading list of anyone wishing to learn about Europe's largest minority group.

This book was provided by Octopus Publishing for review.

dark

medium-paced

I feel bad for scoring this so low but honestly I felt whilst reading this that the narrator just couldn't be arsed. The holocaust is and remains to be one of the most harrowing things to ever happen in our history and 99% we only hear about the Jewish peoples plight. This was so nonchalant.

A Gypsy in Auschwitz is a harrowing, haunting, emotional and remarkable story about an impoverished but happy German Sinti boy who was forced into an encampment outside of Berlin called Marzahn. Otto describes his life living mostly with his loving grandmother who meted out unique "punishment" when necessary. He also details school (including cleanliness rules) and having to leave at 13 to help his grandmother. At the age of 15 he was taken to Auschwitz and recounts horrific conditions there including Dr. Mengele's selections, lice infestations, humiliation, torture, extreme hunger, beatings and murder which happened so regularly he became numb to it. He details killing camp hierarchy. But he also describes unexpected acts of mercy such as a gift of jam. He was also very enterprising...and and had to be to survive. So many difficult anecdotes such as the dog biscuits and cement bags gave me goosebumps. Otto also wrote about the impact on his life atter.

Not only did he suffer unimaginably at Aushwitz but also at Buechenwald and Bergen Belsen. Thousands did not survive the days after liberation. The stories are written candidly with Otto's whole heart. He did not gloss over grotesque and disturbing details. Though I have read many, many books on the Holocaust each one never fails to move me and this one did in its rawness and powerful evocativeness. It was fascinating to learn more about the Sinti in general.

Those interested in learning more about the Holocaust shouldn't miss this awful yet achingly beautiful book. Be sure to read all the notes in the back. The photographs add an even greater personal and memorable touch.

My sincere thank you to Octopus Publishing US and NetGalley for the honour of reading this deeply touching and important true story. It should be required reading for everyone.

Not only did he suffer unimaginably at Aushwitz but also at Buechenwald and Bergen Belsen. Thousands did not survive the days after liberation. The stories are written candidly with Otto's whole heart. He did not gloss over grotesque and disturbing details. Though I have read many, many books on the Holocaust each one never fails to move me and this one did in its rawness and powerful evocativeness. It was fascinating to learn more about the Sinti in general.

Those interested in learning more about the Holocaust shouldn't miss this awful yet achingly beautiful book. Be sure to read all the notes in the back. The photographs add an even greater personal and memorable touch.

My sincere thank you to Octopus Publishing US and NetGalley for the honour of reading this deeply touching and important true story. It should be required reading for everyone.