Take a photo of a barcode or cover

funny

reflective

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

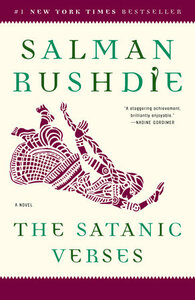

Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses is an often touching, occasionally brilliant, and always entertaining novel. Over 500 pages, Rushie ties together exploration of such themes as the crass consumerism of modern culture, the Indian immigrant experience in England, the origin of Islam in the idolatry of the Arabian peninsula, and the nebulous duality of good and evil. However, it is such a good time that one almost feels that the novel is too entertaining, that it doesn't maintain the decorum that Great Literature is supposed to have.

The novel begins as the Indian movie star Gibreel Farishta and Bombay-born Englishman Saladin Chamcha fall from the sky, their London-bound airliner having been blown up by Sikh nationalists. Miraculously they survive the fall of thirty thousand feet and wash up on an English beach. From here, Chamcha, arrested by police believing he is an illegal immigrant, begins to change into a devil, growing horns and cloven hooves. Farishta goes the opposite way, he becomes his namesake archangel and starts to have strange dreams, in which the reader is transported to, among other places, Mecca in the time of the prophet “Mahound”. Although Farishta and Chamcha are now total opposites morally according to appearance, each continues to live their lives in an unpredictable fashion, and the ending, with Farishta's Joycean soliliquoy is truly a tour de force. The transformation and subsequent experiences of Farishta and Chamcha form the main point of The Satanic Verses: there are no polar opposites, no God and no Satan, but rather ready two sides of a single coin. Rushdie has stated that one of his greatest influences in writing this novel was Mikhail Bulgakov's anti-Soviet satire The Master and Margarita, a book in which the devil is, ironically, made a suave hero. With such inspiration, it's plain that Rushdie wants to present an alternate view of human character, and The Satanic Verses triumphantly rises above its predecessor, Bulgakov's rather shabby novel.

While most people are vaguely aware that the publication of The Satanic Verses resulted in Rushie being forced to go into hiding after Iranian clerics led by the ayatollah Khomeini issued a death fatwa, few know just why the novel led to its author fearing for his life. Rushdie, born a Muslim, was sentenced not for merely speaking against Islam, which millions of people do daily. Rather, it was for "apostasy", or attempting to leave Islam once he was already a Muslim. According to the Qu'ran, attempting to leave Islam is to be punished by death. The book brought on this tempest in two ways. One is the book's antepenultimate section, “Return to Jahilia” in which Rushdie openly declares – in a clever way which I shall not spoil for the reader – that he now believes Islam is a total sham. The second is the pathetic character of the exiled Imam, who is a thinly valid allusion to Khomeini himself. Of course, this all came to the attention of hard-line clerics by the book's skewering portrayal of the founding of the religion and repeated jabs against Muhammad's favourite wife Ayesha.

The Satanic Verses does have one flaw, however, which for me made it only a four-star work: Rushdie often weaves in quotations and allusions to literature without doing anything meaningful with them. Rather, it seems like he is regurgitating the Western tradition in order to add further weight to his already excellent work. Perhaps Rushdie, like his character Saladin Chamcha, feels he must wholeheartedly embrace Englishness and show it off for his readers.

I'd certainly recommend The Satanic Verses. While not a perfect novel, it is one of the most worthwhile reads in contemporary English literature, and spurs the reader to learn about many of the topics Rushdie presented, such as the archaeological exploration of early Islam, the experience of Indian and Pakistani immigrants to London, and religious fundamentalism. Furthermore, since the novel caused such a tempest in the media and was brought to the attention of the world, it's important to read the novel to understand exactly why the fatwa happened.

The novel begins as the Indian movie star Gibreel Farishta and Bombay-born Englishman Saladin Chamcha fall from the sky, their London-bound airliner having been blown up by Sikh nationalists. Miraculously they survive the fall of thirty thousand feet and wash up on an English beach. From here, Chamcha, arrested by police believing he is an illegal immigrant, begins to change into a devil, growing horns and cloven hooves. Farishta goes the opposite way, he becomes his namesake archangel and starts to have strange dreams, in which the reader is transported to, among other places, Mecca in the time of the prophet “Mahound”. Although Farishta and Chamcha are now total opposites morally according to appearance, each continues to live their lives in an unpredictable fashion, and the ending, with Farishta's Joycean soliliquoy is truly a tour de force. The transformation and subsequent experiences of Farishta and Chamcha form the main point of The Satanic Verses: there are no polar opposites, no God and no Satan, but rather ready two sides of a single coin. Rushdie has stated that one of his greatest influences in writing this novel was Mikhail Bulgakov's anti-Soviet satire The Master and Margarita, a book in which the devil is, ironically, made a suave hero. With such inspiration, it's plain that Rushdie wants to present an alternate view of human character, and The Satanic Verses triumphantly rises above its predecessor, Bulgakov's rather shabby novel.

While most people are vaguely aware that the publication of The Satanic Verses resulted in Rushie being forced to go into hiding after Iranian clerics led by the ayatollah Khomeini issued a death fatwa, few know just why the novel led to its author fearing for his life. Rushdie, born a Muslim, was sentenced not for merely speaking against Islam, which millions of people do daily. Rather, it was for "apostasy", or attempting to leave Islam once he was already a Muslim. According to the Qu'ran, attempting to leave Islam is to be punished by death. The book brought on this tempest in two ways. One is the book's antepenultimate section, “Return to Jahilia” in which Rushdie openly declares – in a clever way which I shall not spoil for the reader – that he now believes Islam is a total sham. The second is the pathetic character of the exiled Imam, who is a thinly valid allusion to Khomeini himself. Of course, this all came to the attention of hard-line clerics by the book's skewering portrayal of the founding of the religion and repeated jabs against Muhammad's favourite wife Ayesha.

The Satanic Verses does have one flaw, however, which for me made it only a four-star work: Rushdie often weaves in quotations and allusions to literature without doing anything meaningful with them. Rather, it seems like he is regurgitating the Western tradition in order to add further weight to his already excellent work. Perhaps Rushdie, like his character Saladin Chamcha, feels he must wholeheartedly embrace Englishness and show it off for his readers.

I'd certainly recommend The Satanic Verses. While not a perfect novel, it is one of the most worthwhile reads in contemporary English literature, and spurs the reader to learn about many of the topics Rushdie presented, such as the archaeological exploration of early Islam, the experience of Indian and Pakistani immigrants to London, and religious fundamentalism. Furthermore, since the novel caused such a tempest in the media and was brought to the attention of the world, it's important to read the novel to understand exactly why the fatwa happened.

challenging

funny

mysterious

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

challenging

funny

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Complicated

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

Was due back to the library before I could finish 😭

This is a very difficult book to rate because I have such mixed feelings about its different aspects. I’ll preface this review with the fact that I started this book because of its banning in Iran and wasn’t well versed on Indian or Muslim culture and so did find myself a little confused at some points but I also feel like I have learned a lot in regards to this.

The book started with my least favourite of the three story threads, Saladin and Gibreel in the current day. This beginning was tough to get through due to its aggressive tide of words and lack of compelling story to get me interested from the start. Rushdie had a tendency to throw words together into a sludge of confusing English which I could not enjoy from a stylistic perspective (but I think that is very much a personal taste situation). I found all the characters in the modern story line to be intensely unlikeable and it made it difficult to enjoy their story, only Saladin eventually began to be slightly redeemed but even so, not to a point where I actually liked his character, it was just better than Gibreel. Though one redeeming factor of this story thread is that I felt I got to see parts of England from perspectives I have not seen in many places before, and Rushdie made some very apt subtle and not so subtle commentary on English society.

However, the other two story threads, the dream sequences, were where I think Rushdie’s story shone. These storylines carried most of Rushdie’s theological examination while also being so much more intriguing and gripping than the main story line and really saved the book in my estimation. I particularly appreciated how Rushdie criticised organised religion while still not shying away from using fantastical elements to present the idea that while religion could indeed be true, it is not necessarily always good.

The exploration into what is good/God and what is evil/Shaitan built up most of the book which I found to be an interesting but not particularly innovative theme. However, Rushdie excelled in his exploration of organised religion. I loved the allusion to religion beginning as a positive force of belief and faith in betterment of people and community and turning into a restrictive control mechanism used by the chosen few. Rushdie also looked deeply into the masses generally using religion for personal gain or to fit in, but also how it can instead lead to negative impact when their faith blinds them to reality and even morality and how organised religions have a tendency to chew people up and spit them out broken.

Overall, definitely worth a read for the exploration of religion and the fun dream sequences but be prepared to suffer through Part 1 and its hodge-podge attack on the English language.

The book started with my least favourite of the three story threads, Saladin and Gibreel in the current day. This beginning was tough to get through due to its aggressive tide of words and lack of compelling story to get me interested from the start. Rushdie had a tendency to throw words together into a sludge of confusing English which I could not enjoy from a stylistic perspective (but I think that is very much a personal taste situation). I found all the characters in the modern story line to be intensely unlikeable and it made it difficult to enjoy their story, only Saladin eventually began to be slightly redeemed but even so, not to a point where I actually liked his character, it was just better than Gibreel. Though one redeeming factor of this story thread is that I felt I got to see parts of England from perspectives I have not seen in many places before, and Rushdie made some very apt subtle and not so subtle commentary on English society.

However, the other two story threads, the dream sequences, were where I think Rushdie’s story shone. These storylines carried most of Rushdie’s theological examination while also being so much more intriguing and gripping than the main story line and really saved the book in my estimation. I particularly appreciated how Rushdie criticised organised religion while still not shying away from using fantastical elements to present the idea that while religion could indeed be true, it is not necessarily always good.

The exploration into what is good/God and what is evil/Shaitan built up most of the book which I found to be an interesting but not particularly innovative theme. However, Rushdie excelled in his exploration of organised religion. I loved the allusion to religion beginning as a positive force of belief and faith in betterment of people and community and turning into a restrictive control mechanism used by the chosen few. Rushdie also looked deeply into the masses generally using religion for personal gain or to fit in, but also how it can instead lead to negative impact when their faith blinds them to reality and even morality and how organised religions have a tendency to chew people up and spit them out broken.

Overall, definitely worth a read for the exploration of religion and the fun dream sequences but be prepared to suffer through Part 1 and its hodge-podge attack on the English language.

adventurous

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

This book took me FOREVER to get through. It had good moments so that's why it gets 4 stars.

Prachtig proza en een meeslepend, ingewikkeld verhaal (een boek waar je echt in moet komen), ondanks dat ik een duidelijk aanwezige diepere laag over (uit) de koran niet of nauwelijks begrijp.

funny

reflective

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

a truly epic tale of encounter, identity and change I feel like I've read 50 stories each relating to the human experience in a profound way