Take a photo of a barcode or cover

As I’ve noted in previous posts, I have a job that has expected and unexpected downtime on a regular basis, so I bring whatever book I am currently reading with me nearly everywhere I go. As way of small conversation, I get asked almost daily what I’m reading, what it’s about, how I like it. The responses to my answers concerning John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor have been quite amusing. When I read the title and hold up the book to reveal its cover, which has a colored wood-carving-style illustration of a man in colonial dress and a tri-cornered hat reclining under a tree with a sack of tobacco, an opened book, and a long-stemmed pipe, the most common reaction is a confused, panic look that tells me they don’t know if they should respond with sympathy, horror, or excitement. Then as I explain that it’s a novel from 1960 set in England and Colonial America at the end of the 17th century about a 30-year-old virgin trying to find his claim to fame as the Poet Laureate of Maryland and all the misadventures he has, the confused look only gets more desperate. Then I add that it is written in the style of 18th century novels like the ones Henry Fielding wrote. Oh. Wow. How quickly can we change topics, their eyes plead.

No matter how much I effused about how fantastic the book is, I could not make anyone interested in reading the book much less eager to find out what makes the book so brilliant.

The Sot-Weed Factor is nothing short of amazing. From the construction of the sentences to the tangling and untangling of the grand arc of the plot, John Barth does everything right. It is a book that is intelligent, fun, bawdy, insightful, wandering, focused, and a joy to get lost in. The choice to use the language and structure of the 18th century novel may seem like a gimmick at first, but the style is in fact critical to the feel and thrust of the novel. The narrator, though not actually a character in the novel, becomes essentially that, and it is impossible to separate the tone and presentation from the substance of the novel. I could not imagine this story being told in any other way. To use 20th century language and sensibility to render the tale would be to make the world created at odds with our relationship to it as readers. Barth employs instead an immersion technique. When I think of the breadth of the story and Barth’s commitment to understanding the language, the sentence structures, the idioms, and the style of writing he is imitating, I am awestruck, even more so when I realize that he has managed to make the style his own. If the plot and substance were nothing more than hollow playthings, I would be in love with this book.

But the plot and substance are as dazzling as the prose. Not only does Barth twist and turn the plot, mercilessly torture and tickle his characters, but he does so with a sense of thematic purpose. In his introduction to the novel, written 26 years after the novel was published, Barth notes that the theme of his grand opus is innocence: “I came to understand that innocence, not nihilism, was my real theme, and had been all along, though I’d been too innocent myself to realize that fact. More particularly, I came to appreciate what I have called the ‘tragic view’ of innocence: that it is, or can become, dangerous, even culpable; that where it is prolonged or artificially sustained, it becomes arrested development, potentially disastrous to the innocent himself and to bystanders innocent or otherwise; that what is to be valued, in nations as well as in individuals, is not innocence but wise experience.” But I add to Barth’s evaluation my own: that this book is about identity, who we are, and how we know ourselves.

I could point out dozens of recurring themes and tropes in the novel, but like tributaries feeding a raging river, they all trickle back to the question of identity.

For example, there is the theme of storytelling throughout the novel. Everyone Ebenezer (our protagonist) encounters has a story to relate to him. In fact, at times the plot feels like a string of short stories. Through these stories, Ebenezer comes to understand how the world works, as he travels down the road from innocence to wise experience, and who he is in relation to all these others. The stories are filled with truths and lies as everyone attempts to define themselves and their place in the world, even if only to advantage themselves or manipulate poor Ebenezer. There is an hilarious scene in the first quarter of the novel, in which Eben, stuck in a stable with no pants and covered in his own shit, tries to figure out how to clean himself. A man of learning, he decides to lean on the brilliant minds that came before him, searching the annals of literature for a solution to his problem. It is a ridiculous and beautiful pursuit that ends with him finding no real-life application of his literary predecessors. But it is precisely this sort of real-life knowledge that comes from the stories he gets from his fellow travelers. In the end, Ebenezer is right to search through previous human experience, but he goes to the wrong source. And every story he encounters and tucks away helps him to understand himself and his relationship to the world. Experience is self-knowledge.

There are aphorisms; discussion of cosmophilism; a backdrop of political intrigue, revolutions and opium trafficking; a look into twins; the power and ramifications of signing your name; disguises and stolen identities; slavery and indentured servitude; laws and manipulative power—dozens of thematic variations that play like individual instruments in the creation of a grand concerto. For the analytical reader, there is so much to feast upon, so many connections to make, and as much as I would like to lay out everything I discovered here, I will let you do the discovering for yourself. But that can only happen if you pick up the book and take the journey yourself. If you do, you won’t regret it.

No matter how much I effused about how fantastic the book is, I could not make anyone interested in reading the book much less eager to find out what makes the book so brilliant.

The Sot-Weed Factor is nothing short of amazing. From the construction of the sentences to the tangling and untangling of the grand arc of the plot, John Barth does everything right. It is a book that is intelligent, fun, bawdy, insightful, wandering, focused, and a joy to get lost in. The choice to use the language and structure of the 18th century novel may seem like a gimmick at first, but the style is in fact critical to the feel and thrust of the novel. The narrator, though not actually a character in the novel, becomes essentially that, and it is impossible to separate the tone and presentation from the substance of the novel. I could not imagine this story being told in any other way. To use 20th century language and sensibility to render the tale would be to make the world created at odds with our relationship to it as readers. Barth employs instead an immersion technique. When I think of the breadth of the story and Barth’s commitment to understanding the language, the sentence structures, the idioms, and the style of writing he is imitating, I am awestruck, even more so when I realize that he has managed to make the style his own. If the plot and substance were nothing more than hollow playthings, I would be in love with this book.

But the plot and substance are as dazzling as the prose. Not only does Barth twist and turn the plot, mercilessly torture and tickle his characters, but he does so with a sense of thematic purpose. In his introduction to the novel, written 26 years after the novel was published, Barth notes that the theme of his grand opus is innocence: “I came to understand that innocence, not nihilism, was my real theme, and had been all along, though I’d been too innocent myself to realize that fact. More particularly, I came to appreciate what I have called the ‘tragic view’ of innocence: that it is, or can become, dangerous, even culpable; that where it is prolonged or artificially sustained, it becomes arrested development, potentially disastrous to the innocent himself and to bystanders innocent or otherwise; that what is to be valued, in nations as well as in individuals, is not innocence but wise experience.” But I add to Barth’s evaluation my own: that this book is about identity, who we are, and how we know ourselves.

I could point out dozens of recurring themes and tropes in the novel, but like tributaries feeding a raging river, they all trickle back to the question of identity.

For example, there is the theme of storytelling throughout the novel. Everyone Ebenezer (our protagonist) encounters has a story to relate to him. In fact, at times the plot feels like a string of short stories. Through these stories, Ebenezer comes to understand how the world works, as he travels down the road from innocence to wise experience, and who he is in relation to all these others. The stories are filled with truths and lies as everyone attempts to define themselves and their place in the world, even if only to advantage themselves or manipulate poor Ebenezer. There is an hilarious scene in the first quarter of the novel, in which Eben, stuck in a stable with no pants and covered in his own shit, tries to figure out how to clean himself. A man of learning, he decides to lean on the brilliant minds that came before him, searching the annals of literature for a solution to his problem. It is a ridiculous and beautiful pursuit that ends with him finding no real-life application of his literary predecessors. But it is precisely this sort of real-life knowledge that comes from the stories he gets from his fellow travelers. In the end, Ebenezer is right to search through previous human experience, but he goes to the wrong source. And every story he encounters and tucks away helps him to understand himself and his relationship to the world. Experience is self-knowledge.

There are aphorisms; discussion of cosmophilism; a backdrop of political intrigue, revolutions and opium trafficking; a look into twins; the power and ramifications of signing your name; disguises and stolen identities; slavery and indentured servitude; laws and manipulative power—dozens of thematic variations that play like individual instruments in the creation of a grand concerto. For the analytical reader, there is so much to feast upon, so many connections to make, and as much as I would like to lay out everything I discovered here, I will let you do the discovering for yourself. But that can only happen if you pick up the book and take the journey yourself. If you do, you won’t regret it.

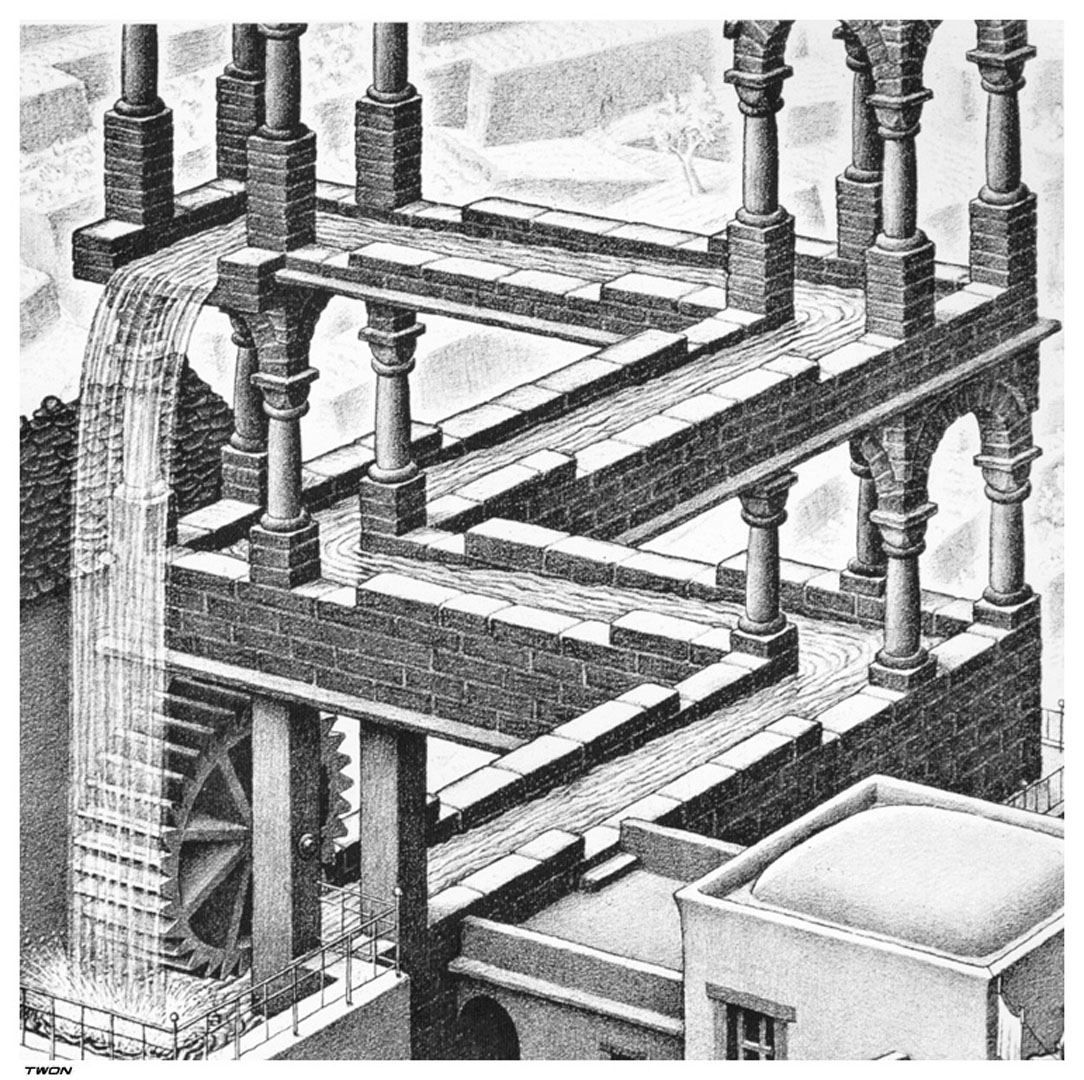

Escher: Sphere, 1942, Maple, diameter 235mm

I visited the Escher museum in The Hague recently. It was a real treat because I've been fascinated by Escher's work since I first saw his ‘Hand Drawing Itself’

Spoiler

Escher seems to enjoy astonishment too. The works I saw at the museum, and in the anthology I bought afterwards, are truly astonishing, and while at first I thought they were simply complex feats of magic and illusion, little by little I began to see meaning in them. Escher, in his own way, is a spinner of story cycles even if his stories are not at first obvious. With careful observation of the different elements, the parts become relatively clear, the method is understood, and the entire work becomes accessible. This is easier when we understand the preposterous parallels of his graphic language, the way he suggests the spatial in the flat and the flat in the spatial.

Spoiler

The works that most clearly demonstrate his storytelling ability are his series of Metamorphoses. I had never realised how many of these he had done. Here are just two examples:

Spoiler

Like a writer, he had certain themes he reworked constantly in his series. The Angel versus Devil sphere I used at the beginning of the review illustrates one of them: the dark side of our world versus the brighter side. In one of his Metamorphoses, day becomes night as black birds turn into white ones.

Spoiler

In another, pure white doves become fish which turn into great black toads which then become fierce looking birds before turning back into innocent white doves again.

Spoiler

At this point you are probably thinking that I’ve mistaken the page and instead of this being a review of John Barth's [b:The Sot-Weed Factor|24835|The Sot-Weed Factor|John Barth|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1349029340l/24835._SY75_.jpg|457683], it is instead a review of [b:The Magic of M.C. Escher|16283911|The Magic of M.C. Escher|J.L. Locher|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1358753359l/16283911._SX50_.jpg|545735].

The truth is, this digression has served to make a point: we can do what we like in a review, meta and morph it however we choose just as John Barth does in his fiction: he thumbs his nose at literary convention and revels in piling up absurd coincidences and preposterous parallels. He distorts our perceptions so that we can no longer be sure of what we see. He shifts the poles of ‘morality’ as he pleases, angels are devils and devils are angels by turns. And civilisation? Where on this earthly sphere is that to be found? Certainly not where we tend to think.

His is spectacular story-telling, designed to astonish, and not averse to far more outlandish digressions than I’ve essayed here. He uses such obscure language and phraseology that it can confuse the reader at the beginning, but it only takes a short time to adjust to it and then everything is relatively clear and transparent.

One of his favourite strategies is metamorphosis: characters are rarely what they seem. They don disguises as smoothly and as frequently as the tessellated images in this Escher print.

Spoiler

Sometimes, however, the metamorphosis is carried out by the trials of life itself - this is the case for women characters more frequently than for male characters. Eve is never done paying the price of seduction it seems. The main character is one of the few who manage to magically retain a dove-like innocence in spite of passing through many tribulations and transmogrifications.

The entire book can be seen as a kind of giant metamorphosis. Starting out as straight historical fiction, it seems to pass through many guises from sharp satire to outright farce. We catch glimpses of authors and works we know in its pages, from Tristram Shandy to Don Quixote, from Rabelais to Shakespeare, from Joyce to the Bible. The only thing that’s missing is a whale!

…………………………………

In spite of my little shill-I, shall-I shuffle near the mid-point of this book when I was almost taken captive by the pirate ship Morpheides, I made it, will-he, nill-he, to as neat an 'alls-well that ends-well' summing-up as ever Shakespeare summoned up, and which Barth justifies with such wonderful casuistry that I declare him Saint John the Chronicler, patron saint of story-tellers henceforth and forever.

Read it and indulge in laughters low.

Amen.

fast-paced

adventurous

dark

funny

medium-paced

Interminable and middling. Way too long for the entertainment value. Just okay.

adventurous

challenging

fast-paced

adventurous

funny

hopeful

lighthearted

relaxing

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

adventurous

challenging

emotional

funny

informative

lighthearted

One of the funniest books ever written. A parody of historical fiction that is itself historical fiction.