You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

challenging

informative

reflective

fast-paced

informative

reflective

sad

fast-paced

challenging

emotional

informative

reflective

medium-paced

I have so many thoughts about this one, but they're all over the place and I'm afraid I won't remember them all, but I'll try to put them in some sort of order.

This is the third book read for my genetic counselling book club in 2025, which is a book club I found through linked in when I was still researching and applying for GC master's programs, and it was also on the list for continuing education credits for NSGC and CBGC, which threw me a bit because so far all our books have been very genetics-based, focusing on the cell, specific genetic mutations and syndromes, and scientific research. But after reading it, I completely understand why it's on the list and appreciate that it was put on my radar.

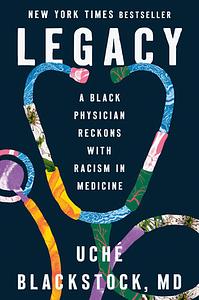

This book is a loving tribute to Dr. Uché Blackstock's mother, a memoir of her journey though the American education and health system, an examination of the history of racism in healthcare and the ways it continues to manifest today, and a call to action to do better, now. I think it succeeds at the first and last items best. The memoir portion was somewhat surface level, and the history portion more of an overview/summary, but the ways she related those to the American healthcare system today, and how it continues to fail Black people and people of colour, was wonderfully laid out, and I really appreciate the itemized lists of tangible ways to make change. I also felt she honoured her mother beautifully, and I was not expecting to cry on the subway while reading this, but I did.

Genetic counselling may not be primary medicine (yet?) but it is provided within the framework of a healthcare institution that has abused, taken advantage of, excluded, minimized, and dismissed Black people and the repercussions of that history are still being felt today, along with continued discrimination and lack of understanding. The ways of addressing this injustice so far have been anemic, lazy, and unfocused, with the proliferation of DEI initiatives often used as a form of lip service, a way to check a box and move on from having to do any real work, and of putting the onus of change on Black people when they were not the people who built the system in the first place.

I'm going to be studying in the US, and the genetic counselling program I've matched with made a strong point of highlighting the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion in our studies, even as the current presidential administration wages its own loud and obnoxious war against the very concept. I hope SLC will do a good job of providing an education that celebrates and embraces diverse backgrounds and the richness of cultural experiences and contexts that make up the US and North America as a whole. I don't know where I'll end up working after school, but I'm not so naive as to think that Canada has no issues with systemic racism in healthcare and education, so I hope I'll be able to use the awareness and knowledge base gained from reading this book to ensure that any work I do within the system is sensitive, and to do what I can to call out and address unfairness when I see it, and to support racialized patients and colleagues.

I read this on Libby, so I've copied out some quotes that stood out since I wasn't able to do the Kindle highlight thing I've gotten so used to:

"...people like my father, coming to the US from the African diaspora, can have excellent health outcomes when they arrive in this country, but for the second generation of their families those outcomes decline, becoming comparable to Black Americans whose enslaved ancestors were brought here in chains" - This shocked me. This is insane.

"Recent studies point to the continued overrepresentation of white patients in clinical oncology trials, which may be another reason for the unfavorable outcomes we see for Black cancer patients. For decades, Black patients have been disproportionately underrepresented in cancer studies, the results of which are generally assumed to be applicable to everyone. But how can we be certain of universal applicability if Black people are excluded from trials in the first place?" - Similar to excluding women from clinical trials and then acting shocked when drugs affect them differently, which I know is why intersectional feminism is so important. It also makes me wonder, though, about how we phrase things like "there's no biological difference between men/women/white/Black people" because I understand this to be true in terms of our humanity and how we all deserve to be valued and respected and given equal opportunities, but clearly isn't medically true if drugs affect us all differently; are there nuances to the way "biological" is used that I'm missing? is it what ASPECTS of the biology is different? and since different people react differently to different drugs, does that mean that we need to divide the categories into people with x, y, and z genes rather than male/female/race/height/weight? but if we're zooming in that far, how do you even run clinical trials? and this is what I mean when I say my thoughts are all over the place...

"My professors were overwhelmingly white men; I could count the number of Black faculty members on one hand. From our instructors, we learned to see the world through what was considered an entirely “scientific, objective, and evidence-based” lens. These men were immensely confident, seemingly competent authorities on their subjects. It was not our job to doubt them, it was our job to absorb everything they told us."

"The information imparted to us in the classrooms and on the wards was presented as “factual data” and “research-driven” without any sociopolitical context. I now realize that this so-called objectivity was anything but."

"Such experiments and interventions that were carried out on Black Americans have gone on to create what has often been described as “institutional distrust”—in which Black people are perceived to be reluctant to interact with a medical system that has historically perpetrated abuses upon them. However, this term pathologizes and places the blame on Black people. Instead, this phenomenon is better described as “institutional untrustworthiness,” whereby institutions have shown themselves to be untrustworthy to our communities thanks to a litany of abuses and mistreatment enacted against Black Americans by the health-care system." - I like this. I want to underline "institutional untrustworthiness" about five times.

"'stereotype threat'—a psychological phenomenon in which an individual feels at risk of confirming a negative stereotype about a group they identify with."

"But in the end, all the self-care in the world couldn’t make up for the long hours and intense stress of the job."

"Midwives in general began to be sidelined, regarded as old-fashioned and unsafe, even though these perceptions were far from accurate. In fact, a New York Academy of Medicine study in 1932 found that home births attended by midwives had the lowest maternal mortality rates of any setting. Despite this, ob-gyns and the medicalized model of managing pregnancy and childbirth became the norm." - I hate that, growing up, I thought midwifery was quackery on par with essential oils and crystals. I don't know where I picked that up, but it was years before I understood that just because midwives and doulas don't necessarily have medical degrees, that doesn't mean their knowledge isn't valuable and evidence-based.

"Yet, I found it ironic and infuriating that we, Black faculty members, were being given the complex and overwhelming task of remedying the outcomes of centuries of institutionalized racism—problems we did not create in the first place. [...] I was never told, “Uché, this is your role, and we are going to invest in you and make sure you get the training and support that you need to be successful in your role.” In some ways, that’s the nature of academic medicine—you get thrown into positions and you either sink or swim, or you learn by doing. At the same time, it’s hard to do substantive work or even have a positive outlook when you don’t have the people, the resources, or the institutional support to effect real change."

"Every newsletter that the office published had to be vetted by the senior deans (older white men) for inflammatory content." - FFS. <italics>We want to be celebrated for our efforts without ever actually doing a damned thing or ever having to feel even a little bit bad!</italics>

"The pandemic rolled on, leaving hundreds of thousands of lives in its wake." - It's beside the point, so I didn't mention it in my main review, but odd sentences like this happen quite a bit in the book and I'm not sure if it's because I read a digital copy and there were words missing, or if it's another entry in the "HIRE ME TO BE AN EDITOR" log, because shouldn't this be "thousands of lives <italics>devastated</italics> in its wake" or "crushed" or "destroyed" or something? It didn't just leave <italics>lives</italics> in its wake.

"In 2018 alone, health-care companies spent nearly $568 million on lobbying, more than any other industry. Imagine what could be done with that money if it were directed toward actually caring for patients in need." - Insert rage gif from Inside Out here.

"The maternal mortality rate is now higher than it was twenty-five years ago. Black infants are more than twice as likely to die in their first year of life as white infants, a wider inequity now than fifteen years before the end of slavery (although it’s important to note that enslavers had a financial interest in keeping Black babies alive because they possessed monetary value)." - Again, this is insane.

"What my mother wrote in 1996 remains true, appallingly so. Not only has the percentage of Black physicians failed to increase but numerous racial health inequities have actually worsened since the 1990s." - ARGH.

This is the third book read for my genetic counselling book club in 2025, which is a book club I found through linked in when I was still researching and applying for GC master's programs, and it was also on the list for continuing education credits for NSGC and CBGC, which threw me a bit because so far all our books have been very genetics-based, focusing on the cell, specific genetic mutations and syndromes, and scientific research. But after reading it, I completely understand why it's on the list and appreciate that it was put on my radar.

This book is a loving tribute to Dr. Uché Blackstock's mother, a memoir of her journey though the American education and health system, an examination of the history of racism in healthcare and the ways it continues to manifest today, and a call to action to do better, now. I think it succeeds at the first and last items best. The memoir portion was somewhat surface level, and the history portion more of an overview/summary, but the ways she related those to the American healthcare system today, and how it continues to fail Black people and people of colour, was wonderfully laid out, and I really appreciate the itemized lists of tangible ways to make change. I also felt she honoured her mother beautifully, and I was not expecting to cry on the subway while reading this, but I did.

Genetic counselling may not be primary medicine (yet?) but it is provided within the framework of a healthcare institution that has abused, taken advantage of, excluded, minimized, and dismissed Black people and the repercussions of that history are still being felt today, along with continued discrimination and lack of understanding. The ways of addressing this injustice so far have been anemic, lazy, and unfocused, with the proliferation of DEI initiatives often used as a form of lip service, a way to check a box and move on from having to do any real work, and of putting the onus of change on Black people when they were not the people who built the system in the first place.

I'm going to be studying in the US, and the genetic counselling program I've matched with made a strong point of highlighting the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion in our studies, even as the current presidential administration wages its own loud and obnoxious war against the very concept. I hope SLC will do a good job of providing an education that celebrates and embraces diverse backgrounds and the richness of cultural experiences and contexts that make up the US and North America as a whole. I don't know where I'll end up working after school, but I'm not so naive as to think that Canada has no issues with systemic racism in healthcare and education, so I hope I'll be able to use the awareness and knowledge base gained from reading this book to ensure that any work I do within the system is sensitive, and to do what I can to call out and address unfairness when I see it, and to support racialized patients and colleagues.

I read this on Libby, so I've copied out some quotes that stood out since I wasn't able to do the Kindle highlight thing I've gotten so used to:

"...people like my father, coming to the US from the African diaspora, can have excellent health outcomes when they arrive in this country, but for the second generation of their families those outcomes decline, becoming comparable to Black Americans whose enslaved ancestors were brought here in chains" - This shocked me. This is insane.

"Recent studies point to the continued overrepresentation of white patients in clinical oncology trials, which may be another reason for the unfavorable outcomes we see for Black cancer patients. For decades, Black patients have been disproportionately underrepresented in cancer studies, the results of which are generally assumed to be applicable to everyone. But how can we be certain of universal applicability if Black people are excluded from trials in the first place?" - Similar to excluding women from clinical trials and then acting shocked when drugs affect them differently, which I know is why intersectional feminism is so important. It also makes me wonder, though, about how we phrase things like "there's no biological difference between men/women/white/Black people" because I understand this to be true in terms of our humanity and how we all deserve to be valued and respected and given equal opportunities, but clearly isn't medically true if drugs affect us all differently; are there nuances to the way "biological" is used that I'm missing? is it what ASPECTS of the biology is different? and since different people react differently to different drugs, does that mean that we need to divide the categories into people with x, y, and z genes rather than male/female/race/height/weight? but if we're zooming in that far, how do you even run clinical trials? and this is what I mean when I say my thoughts are all over the place...

"My professors were overwhelmingly white men; I could count the number of Black faculty members on one hand. From our instructors, we learned to see the world through what was considered an entirely “scientific, objective, and evidence-based” lens. These men were immensely confident, seemingly competent authorities on their subjects. It was not our job to doubt them, it was our job to absorb everything they told us."

"The information imparted to us in the classrooms and on the wards was presented as “factual data” and “research-driven” without any sociopolitical context. I now realize that this so-called objectivity was anything but."

"Such experiments and interventions that were carried out on Black Americans have gone on to create what has often been described as “institutional distrust”—in which Black people are perceived to be reluctant to interact with a medical system that has historically perpetrated abuses upon them. However, this term pathologizes and places the blame on Black people. Instead, this phenomenon is better described as “institutional untrustworthiness,” whereby institutions have shown themselves to be untrustworthy to our communities thanks to a litany of abuses and mistreatment enacted against Black Americans by the health-care system." - I like this. I want to underline "institutional untrustworthiness" about five times.

"'stereotype threat'—a psychological phenomenon in which an individual feels at risk of confirming a negative stereotype about a group they identify with."

"But in the end, all the self-care in the world couldn’t make up for the long hours and intense stress of the job."

"Midwives in general began to be sidelined, regarded as old-fashioned and unsafe, even though these perceptions were far from accurate. In fact, a New York Academy of Medicine study in 1932 found that home births attended by midwives had the lowest maternal mortality rates of any setting. Despite this, ob-gyns and the medicalized model of managing pregnancy and childbirth became the norm." - I hate that, growing up, I thought midwifery was quackery on par with essential oils and crystals. I don't know where I picked that up, but it was years before I understood that just because midwives and doulas don't necessarily have medical degrees, that doesn't mean their knowledge isn't valuable and evidence-based.

"Yet, I found it ironic and infuriating that we, Black faculty members, were being given the complex and overwhelming task of remedying the outcomes of centuries of institutionalized racism—problems we did not create in the first place. [...] I was never told, “Uché, this is your role, and we are going to invest in you and make sure you get the training and support that you need to be successful in your role.” In some ways, that’s the nature of academic medicine—you get thrown into positions and you either sink or swim, or you learn by doing. At the same time, it’s hard to do substantive work or even have a positive outlook when you don’t have the people, the resources, or the institutional support to effect real change."

"Every newsletter that the office published had to be vetted by the senior deans (older white men) for inflammatory content." - FFS. <italics>We want to be celebrated for our efforts without ever actually doing a damned thing or ever having to feel even a little bit bad!</italics>

"The pandemic rolled on, leaving hundreds of thousands of lives in its wake." - It's beside the point, so I didn't mention it in my main review, but odd sentences like this happen quite a bit in the book and I'm not sure if it's because I read a digital copy and there were words missing, or if it's another entry in the "HIRE ME TO BE AN EDITOR" log, because shouldn't this be "thousands of lives <italics>devastated</italics> in its wake" or "crushed" or "destroyed" or something? It didn't just leave <italics>lives</italics> in its wake.

"In 2018 alone, health-care companies spent nearly $568 million on lobbying, more than any other industry. Imagine what could be done with that money if it were directed toward actually caring for patients in need." - Insert rage gif from Inside Out here.

"The maternal mortality rate is now higher than it was twenty-five years ago. Black infants are more than twice as likely to die in their first year of life as white infants, a wider inequity now than fifteen years before the end of slavery (although it’s important to note that enslavers had a financial interest in keeping Black babies alive because they possessed monetary value)." - Again, this is insane.

"What my mother wrote in 1996 remains true, appallingly so. Not only has the percentage of Black physicians failed to increase but numerous racial health inequities have actually worsened since the 1990s." - ARGH.

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

informative

reflective

medium-paced

This is a powerful book. Dr. Blackstock delves into her mother's legacy of becoming a physician and how that shaped her and her sister's futures as physicians. However, it wasn't without struggle.

She talks about how she and her mother experienced racism in the workplace. How systematic racism prevented members of the black community and those of lower socioeconomic status from receiving proper care.

It wasn't just a memoir, but also a call to action. While we've made great strides, there is still more that needs to be done.

Sharing her struggles with being the only black physician or being one of X number puts a heavy burden. She mentored young black physicians and was in charge of diversity initiatives that require a lot of mental and physical labor that is often unappreciated.

The story that will probably stay with me is when she cared for a patient having a miscarriage. That whole chapter about caring for 3 specific patients is haunting.

I highly recommend this book!

She talks about how she and her mother experienced racism in the workplace. How systematic racism prevented members of the black community and those of lower socioeconomic status from receiving proper care.

It wasn't just a memoir, but also a call to action. While we've made great strides, there is still more that needs to be done.

Sharing her struggles with being the only black physician or being one of X number puts a heavy burden. She mentored young black physicians and was in charge of diversity initiatives that require a lot of mental and physical labor that is often unappreciated.

The story that will probably stay with me is when she cared for a patient having a miscarriage. That whole chapter about caring for 3 specific patients is haunting.

I highly recommend this book!

challenging

emotional

informative

fast-paced

I loved this. I am not in the medical field but it was part information part memoir which is one of my favorite types of book.

challenging

inspiring

medium-paced

informative

inspiring

sad

tense

slow-paced

Graphic: Racism, Pandemic/Epidemic

Minor: Gun violence, Police brutality, Medical content, Medical trauma