Take a photo of a barcode or cover

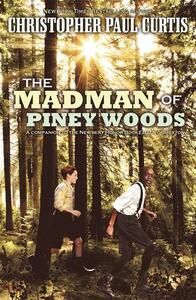

No author hits it out of the park every time. No matter how talented or clever a writer might be, if their heart isn’t in a project it shows. In the case of Christopher Paul Curtis, when he loves what he’s writing the sheets of paper on which he types practically set on fire. When he doesn’t? It’s like reading mold. There’s life there, but no energy. Now in the case of his Newbery Honor book Elijah of Buxton, Curtis was doing gangbuster work. His blend of history and humor is unparalleled and you need only look to Elijah to see Curtis at his best. With that in mind I approached the companion novel to Elijah titled The Madman of Piney Woods with some trepidation. A good companion book will add to the magic of the original. A poor one, detract. I needn’t have worried. While I wouldn’t quite put Madman on the same level as Elijah, what Curtis does here, with his theme of fear and what it can do to a human soul, is as profound and thought provoking as anything he’s written in the past. There is ample fodder here for young brains. The fact that it’s a hoot to read as well is just the icing on the cake.

Two boys. Two lives. It’s 1901, forty years after the events in Elijah of Buxton and Benji Alston has only one dream: To be the world’s greatest reporter. He even gets an apprenticeship on a real paper, though he finds there’s more to writing stories than he initially thought. Meanwhile Alvin Stockard, nicknamed Red, is determined to be a scientist. That is, when he’s not dodging the blows of his bitter Irish granny, Mother O’Toole. When the two boys meet they have a lot in common, in spite of the fact that Benji’s black and Red’s Irish. They've also had separate encounters with the legendary Madman of Piney Woods. Is the man an ex-slave or a convict or part lion? The truth is more complicated than that, and when the Madman is in trouble these two boys come to his aid and learn what it truly means to face fear.

Let’s be plainspoken about what this book really is. Curtis has mastered the art of the Tom Sawyerish novel. Sometimes it feels like books containing mischievous boys have fallen out of favor. Thank goodness for Christopher Paul Curtis then. What we have here is a good old-fashioned 1901 buddy comedy. Two boys getting into and out of scrapes. Wreaking havoc. Revenging themselves on their enemies / siblings (or at least Benji does). It’s downright Mark Twainish (if that’s a term). Much of the charm comes from the fact that Curtis knows from funny. Benji’s a wry-hearted bigheaded, egotistical, lovable imp. He can be canny and completely wrong-headed within the space of just a few sentences. Red, in contrast, is book smart with a more regulation-sized ego but as gullible as they come. Put Red and Benji together and it’s little wonder they're friends. They compliment one another’s faults. With Elijah of Buxton I felt no need to know more about Elijah and Cooter’s adventures. With Madman I wouldn’t mind following Benji and Red's exploits for a little bit longer.

One of the characteristics of Curtis’s writing that sets him apart from the historical fiction pack is his humor. Making the past funny is a trick. Pranks help. An egotistical character getting their comeuppance helps too. In fact, at one point Curtis perfectly defines the miracle of funny writing. Benji is pondering words and wordplay and the magic of certain letter combinations. Says he, “How is it possible that one person can use only words to make another person laugh?” How indeed. The remarkable thing isn’t that Curtis is funny, though. Rather, it’s the fact that he knows how to balance tone so well. The book will garner honest belly laughs on one page, then manage to wrench real emotion out of you the next. The best funny authors are adept at this switch. The worst leave you feeling queasy. And Curtis never, not ever, gives a reader a queasy feeling.

Normally I have a problem with books where characters act out-of-step with the times without any outside influence. For example, I once read a Civil War middle grade novel that shall remain nameless where a girl, without anyone in her life offering her any guidance, independently came up with the idea that “corsets restrict the mind”. Ugh. Anachronisms make me itch. With that in mind, I watched Red very carefully in this book. Here you have a boy effectively raised by a racist grandmother who is almost wholly without so much as a racist thought in his little ginger noggin. How do we account for this? Thankfully, Red’s father gives us an “out”, as it were. A good man who struggles with the amount of influence his mother-in-law may or may not have over her redheaded grandchild, Mr. Stockard is the just force in his son’s life that guides his good nature.

The preferred writing style of Christopher Paul Curtis that can be found in most of his novels is also found here. It initially appears deceptively simple. There will be a series of seemingly unrelated stories with familiar characters. Little interstitial moments will resonate with larger themes, but the book won't feel like it’s going anywhere. Then, in the third act, BLAMMO! Curtis will hit you with everything he’s got. Murder, desperation, the works. He’s done it so often you can set your watch by it, but it still works, man. Now to be fair, when Curtis wrote Elijah of Buxton he sort of peaked. It’s hard to compete with the desperation that filled Elijah’s encounter with an enslaved family near the end. In Madman Curtis doesn’t even attempt to top it. In fact, he comes to his book’s climax from another angle entirely. There is some desperation (and not a little blood) but even so this is a more thoughtful third act. If Elijah asked the reader to feel, Madman asks the reader to think. Nothing wrong with that. It just doesn’t sock you in the gut quite as hard.

For me, it all comes down to the quotable sentences. And fortunately, in this book the writing is just chock full of wonderful lines. Things like, “An object in motion tends to stay in motion, and the same can be said of many an argument.” Or later, when talking about Red's nickname, “It would be hard for even as good a debater as Spencer or the Holmely boy to disprove that a cardinal and a beet hadn’t been married and given birth to this boy. Then baptized him in a tub of red ink.” And I may have to conjure up this line in terms of discipline and kids: “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, but you can sure make him stand there looking at the water for a long time.” Finally, on funerals: “Maybe it’s just me, but I always found it a little hard to celebrate when one of the folks in the room is dead.”

He also creates little moments that stay with you. Kissing a reflection only to have your lips stick to it. A girl’s teeth so rotted that her father has to turn his head when she kisses him to avoid the stench (kisses are treacherous things in Curtis novels). In this book I’ll probably long remember the boy who purposefully gets into fights to give himself a reason for the injuries wrought by his drunken father. And there’s even a moment near the end when the Madman’s identity is clarified that is a great example of Curtis playing with his audience. Before he gives anything away he makes it clear that the Madman could be one of two beloved characters from Elijah of Buxton. It’s agony waiting for him to clarify who exactly is who.

Character is king in the world of Mr. Curtis. A writer who manages to construct fully three-dimensional people out of mere words is one to watch. In this book, Curtis has the difficult task of making complete and whole a character through the eyes of two different-year-old boys. And when you consider that they’re working from the starting point of thinking that the guy’s insane, it’s going to be a tough slog to convince the reader otherwise. That said, once you get into the head of the “Madman” you get a profound sense not of his insanity but of his gentleness. His very existence reminded me of similar loners in literature like Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson or [b:The House of Dies Drear|225725|The House of Dies Drear|Virginia Hamilton|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1389368243s/225725.jpg|218632] by Virginia Hamilton, but unlike the men in those books this guy had a heart and a mind and a very distinctive past. And fears. Terrible, awful fears.

It’s that fear that gives Madman its true purpose. Red’s grandmother, Mother O’Toole, shares with the Madman a horrific past. They’re very different horrors (one based in sheer mind-blowing violence and the other in death, betrayal, and disgust) but the effects are the same. Out of these moments both people are suffering a kind of PTSD. This makes them two sides of the same coin. Equally wracked by horrible memories, they chose to handle those memories in different ways. The Madman gives up society but retains his soul. Mother O’Toole, in contrast, retains her sanity but gives up her soul. Yet by the end of the book the supposed Madman has returned to society and reconnected with his friends while the Irishwoman is last seen with her hair down (a classic madwoman trope as old as Shakespeare himself) scrubbing dishes until she bleeds to rid them of any trace of the race she hates so much. They have effectively switched places.

Much of what The Madman of Piney Woods does is ask what fear does to people. The Madman speaks eloquently of all too human monsters and what they can do to a man. Meanwhile Grandmother has suffered as well but it’s made her bitter and angry. When Red asks, “Doesn’t it seem only logical that if a person has been through all of the grief she has, they’d have nothing but compassion for anyone else who’s been through the same?” His father responds that “given enough time, fear is the great killer of the human spirit.” In her case it has taken her spirit and “has so horribly scarred it, condensing and strengthening and dishing out the same hatred that it has experienced.” But for some the opposite is true, hence the Madman. Two humans who have seen the worst of humanity. Two different reactions. And as with Elijah, where Curtis tackled slavery not through a slave but through a slave’s freeborn child, we hear about these things through kids who are “close enough to hear the echoes of the screams in [the adults’] nightmarish memories.” Certainly it rubs off onto the younger characters in different ways. In one chapter Benji wonders why the original settlers of Buxton, all ex-slaves, can’t just relax. Fear has shaped them so distinctly that he figures a town of “nervous old people” has raised him. Adversity can either build or destroy character, Curtis says. This book is the story of precisely that.

Don’t be surprised if, after finishing this book, you find yourself reaching for your copy of Elijah of Buxton so as to remember some of these characters when they were young. Reaching deep, Curtis puts soul into the pages of its companion novel. In my more dreamy-eyed moments I fantasize about Curtis continuing the stories of Buxton every 40 years until he gets to the present day. It could be his equivalent of Louise Erdrich’s [b:Birchbark House|159666|The Birchbark House|Louise Erdrich|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1280242695s/159666.jpg|154105] chronicles. Imagine if we shot forward another 40 years to 1941 and encountered a grown Benji and Red with their own families and fears. I doubt Curtis is planning on going that route, but whether or not this is the end of Buxton’s tales or just the beginning, The Madman of Piney Woods will leave child readers questioning what true trauma can do to a soul, and what they would do if it happened to them. Heady stuff. Funny stuff. Smart stuff. Good stuff. Better get your hands on this stuff.

For ages 9-12.

Two boys. Two lives. It’s 1901, forty years after the events in Elijah of Buxton and Benji Alston has only one dream: To be the world’s greatest reporter. He even gets an apprenticeship on a real paper, though he finds there’s more to writing stories than he initially thought. Meanwhile Alvin Stockard, nicknamed Red, is determined to be a scientist. That is, when he’s not dodging the blows of his bitter Irish granny, Mother O’Toole. When the two boys meet they have a lot in common, in spite of the fact that Benji’s black and Red’s Irish. They've also had separate encounters with the legendary Madman of Piney Woods. Is the man an ex-slave or a convict or part lion? The truth is more complicated than that, and when the Madman is in trouble these two boys come to his aid and learn what it truly means to face fear.

Let’s be plainspoken about what this book really is. Curtis has mastered the art of the Tom Sawyerish novel. Sometimes it feels like books containing mischievous boys have fallen out of favor. Thank goodness for Christopher Paul Curtis then. What we have here is a good old-fashioned 1901 buddy comedy. Two boys getting into and out of scrapes. Wreaking havoc. Revenging themselves on their enemies / siblings (or at least Benji does). It’s downright Mark Twainish (if that’s a term). Much of the charm comes from the fact that Curtis knows from funny. Benji’s a wry-hearted bigheaded, egotistical, lovable imp. He can be canny and completely wrong-headed within the space of just a few sentences. Red, in contrast, is book smart with a more regulation-sized ego but as gullible as they come. Put Red and Benji together and it’s little wonder they're friends. They compliment one another’s faults. With Elijah of Buxton I felt no need to know more about Elijah and Cooter’s adventures. With Madman I wouldn’t mind following Benji and Red's exploits for a little bit longer.

One of the characteristics of Curtis’s writing that sets him apart from the historical fiction pack is his humor. Making the past funny is a trick. Pranks help. An egotistical character getting their comeuppance helps too. In fact, at one point Curtis perfectly defines the miracle of funny writing. Benji is pondering words and wordplay and the magic of certain letter combinations. Says he, “How is it possible that one person can use only words to make another person laugh?” How indeed. The remarkable thing isn’t that Curtis is funny, though. Rather, it’s the fact that he knows how to balance tone so well. The book will garner honest belly laughs on one page, then manage to wrench real emotion out of you the next. The best funny authors are adept at this switch. The worst leave you feeling queasy. And Curtis never, not ever, gives a reader a queasy feeling.

Normally I have a problem with books where characters act out-of-step with the times without any outside influence. For example, I once read a Civil War middle grade novel that shall remain nameless where a girl, without anyone in her life offering her any guidance, independently came up with the idea that “corsets restrict the mind”. Ugh. Anachronisms make me itch. With that in mind, I watched Red very carefully in this book. Here you have a boy effectively raised by a racist grandmother who is almost wholly without so much as a racist thought in his little ginger noggin. How do we account for this? Thankfully, Red’s father gives us an “out”, as it were. A good man who struggles with the amount of influence his mother-in-law may or may not have over her redheaded grandchild, Mr. Stockard is the just force in his son’s life that guides his good nature.

The preferred writing style of Christopher Paul Curtis that can be found in most of his novels is also found here. It initially appears deceptively simple. There will be a series of seemingly unrelated stories with familiar characters. Little interstitial moments will resonate with larger themes, but the book won't feel like it’s going anywhere. Then, in the third act, BLAMMO! Curtis will hit you with everything he’s got. Murder, desperation, the works. He’s done it so often you can set your watch by it, but it still works, man. Now to be fair, when Curtis wrote Elijah of Buxton he sort of peaked. It’s hard to compete with the desperation that filled Elijah’s encounter with an enslaved family near the end. In Madman Curtis doesn’t even attempt to top it. In fact, he comes to his book’s climax from another angle entirely. There is some desperation (and not a little blood) but even so this is a more thoughtful third act. If Elijah asked the reader to feel, Madman asks the reader to think. Nothing wrong with that. It just doesn’t sock you in the gut quite as hard.

For me, it all comes down to the quotable sentences. And fortunately, in this book the writing is just chock full of wonderful lines. Things like, “An object in motion tends to stay in motion, and the same can be said of many an argument.” Or later, when talking about Red's nickname, “It would be hard for even as good a debater as Spencer or the Holmely boy to disprove that a cardinal and a beet hadn’t been married and given birth to this boy. Then baptized him in a tub of red ink.” And I may have to conjure up this line in terms of discipline and kids: “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, but you can sure make him stand there looking at the water for a long time.” Finally, on funerals: “Maybe it’s just me, but I always found it a little hard to celebrate when one of the folks in the room is dead.”

He also creates little moments that stay with you. Kissing a reflection only to have your lips stick to it. A girl’s teeth so rotted that her father has to turn his head when she kisses him to avoid the stench (kisses are treacherous things in Curtis novels). In this book I’ll probably long remember the boy who purposefully gets into fights to give himself a reason for the injuries wrought by his drunken father. And there’s even a moment near the end when the Madman’s identity is clarified that is a great example of Curtis playing with his audience. Before he gives anything away he makes it clear that the Madman could be one of two beloved characters from Elijah of Buxton. It’s agony waiting for him to clarify who exactly is who.

Character is king in the world of Mr. Curtis. A writer who manages to construct fully three-dimensional people out of mere words is one to watch. In this book, Curtis has the difficult task of making complete and whole a character through the eyes of two different-year-old boys. And when you consider that they’re working from the starting point of thinking that the guy’s insane, it’s going to be a tough slog to convince the reader otherwise. That said, once you get into the head of the “Madman” you get a profound sense not of his insanity but of his gentleness. His very existence reminded me of similar loners in literature like Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson or [b:The House of Dies Drear|225725|The House of Dies Drear|Virginia Hamilton|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1389368243s/225725.jpg|218632] by Virginia Hamilton, but unlike the men in those books this guy had a heart and a mind and a very distinctive past. And fears. Terrible, awful fears.

It’s that fear that gives Madman its true purpose. Red’s grandmother, Mother O’Toole, shares with the Madman a horrific past. They’re very different horrors (one based in sheer mind-blowing violence and the other in death, betrayal, and disgust) but the effects are the same. Out of these moments both people are suffering a kind of PTSD. This makes them two sides of the same coin. Equally wracked by horrible memories, they chose to handle those memories in different ways. The Madman gives up society but retains his soul. Mother O’Toole, in contrast, retains her sanity but gives up her soul. Yet by the end of the book the supposed Madman has returned to society and reconnected with his friends while the Irishwoman is last seen with her hair down (a classic madwoman trope as old as Shakespeare himself) scrubbing dishes until she bleeds to rid them of any trace of the race she hates so much. They have effectively switched places.

Much of what The Madman of Piney Woods does is ask what fear does to people. The Madman speaks eloquently of all too human monsters and what they can do to a man. Meanwhile Grandmother has suffered as well but it’s made her bitter and angry. When Red asks, “Doesn’t it seem only logical that if a person has been through all of the grief she has, they’d have nothing but compassion for anyone else who’s been through the same?” His father responds that “given enough time, fear is the great killer of the human spirit.” In her case it has taken her spirit and “has so horribly scarred it, condensing and strengthening and dishing out the same hatred that it has experienced.” But for some the opposite is true, hence the Madman. Two humans who have seen the worst of humanity. Two different reactions. And as with Elijah, where Curtis tackled slavery not through a slave but through a slave’s freeborn child, we hear about these things through kids who are “close enough to hear the echoes of the screams in [the adults’] nightmarish memories.” Certainly it rubs off onto the younger characters in different ways. In one chapter Benji wonders why the original settlers of Buxton, all ex-slaves, can’t just relax. Fear has shaped them so distinctly that he figures a town of “nervous old people” has raised him. Adversity can either build or destroy character, Curtis says. This book is the story of precisely that.

Don’t be surprised if, after finishing this book, you find yourself reaching for your copy of Elijah of Buxton so as to remember some of these characters when they were young. Reaching deep, Curtis puts soul into the pages of its companion novel. In my more dreamy-eyed moments I fantasize about Curtis continuing the stories of Buxton every 40 years until he gets to the present day. It could be his equivalent of Louise Erdrich’s [b:Birchbark House|159666|The Birchbark House|Louise Erdrich|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1280242695s/159666.jpg|154105] chronicles. Imagine if we shot forward another 40 years to 1941 and encountered a grown Benji and Red with their own families and fears. I doubt Curtis is planning on going that route, but whether or not this is the end of Buxton’s tales or just the beginning, The Madman of Piney Woods will leave child readers questioning what true trauma can do to a soul, and what they would do if it happened to them. Heady stuff. Funny stuff. Smart stuff. Good stuff. Better get your hands on this stuff.

For ages 9-12.

Maybe I'm only giving this 3 stars because I wasn't enthralled with the audiobook. I was struck though by how much was going on in this story--at times it felt unwieldy, at other times the stories entwined very well. I really got into the end with the mayor and the madman, and while Grandmother O'Toole described her experience of coming to Canada. It had some really hard-hitting themes, balanced with humor and lighter fare. But wow, there was a lot going on.

Narrators did such a great job giving life to the characters. So beautifully written, I wanted to continue spending time with Benji and Red. Will be happy to learn more about Cooter and Elijah in Elijah of Buxton.

"Our memories are always in the process of falling apart; they're constantly fading."

"Benjamin, what is it you're always doing on and on about wanting to he one day?

-A hermit?

The other job..."

"This is my classroom right here. And these are my teachers. The trees and the sky and the animals and most especially the floor of the forest. If I need to get information on anything that's happened, I look at the ground and it's like I've opened a book."

"Benjamin, what is it you're always doing on and on about wanting to he one day?

-A hermit?

The other job..."

"This is my classroom right here. And these are my teachers. The trees and the sky and the animals and most especially the floor of the forest. If I need to get information on anything that's happened, I look at the ground and it's like I've opened a book."

I found the first part of this book dragged a little bit but I really enjoyed the second part. Wish he had them meet sooner. I loved the history of the time!

Plenty of laughter and tears in this one...such a good listen. Not just for middle-graders—for anyone who enjoys a darn good story.

I waited quite awhile to compose my thoughts about this one because I felt like a needed some time to wrap my head around it. Now that I've also had the chance to discuss it with our Mock Newbery group, I feel like I have a better sense of what I loved about it. Benji and Red are wonderful characters, distinctive and authentically childish in spite of their big dreams and old-fashioned language. Each has multiple layers of interests and abilities, and the people around them are similarly complex, particularly the Madman and Red's grandmother. Curtis presents the historical setting and some truly horrific episodes in history in a way that is accessible to and respectful of a child audience, and the themes of healing, redemption, and prejudice are well-integrated and resist providing easy answers. In addition to having broad appeal for a wide range of readers, it's the best kind of historical fiction novel: emotionally engaging, illuminating, and well-paced.

This is a companion book to [b:Elijah of Buxton|638689|Elijah of Buxton|Christopher Paul Curtis|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1328843610s/638689.jpg|2247514] and takes place several years after the events of that book. Red and Benji are two boys who live around Buxton. Red is an Irish lad who lives with his father and grandmother. Father is a judge and grandmother is a irritable racist who hates pretty much everyone and everything. Benji is a black boy who wants to be a newspaper man. He writes headlines for the big events in his life and even gets an apprenticeship at a newspaper. The two independently meet the Madman of Piney Woods who is a hermit living in the woods. Benji and Red meet about half-way through the book and become friends despite the differences in their backgrounds.

It took me a long time to read this book. It was pretty slow going and I just didn't find it that interesting. I wanted to like it more. I enjoyed Benji and Red, but found their just wasn't enough going on in the book to keep me reading. For being the title of the book the Madman didn't play nearly as big a role as I thought he would. I also wasn't sure how this tied to Elijah of Buxton except the setting until the very end when Elijah was introduced again. There is a lot of good historical information in this book and as always Curtis' writing is wonderful. I just wasn't feeling this book however.

I received a copy of this book from Netgalley.

It took me a long time to read this book. It was pretty slow going and I just didn't find it that interesting. I wanted to like it more. I enjoyed Benji and Red, but found their just wasn't enough going on in the book to keep me reading. For being the title of the book the Madman didn't play nearly as big a role as I thought he would. I also wasn't sure how this tied to Elijah of Buxton except the setting until the very end when Elijah was introduced again. There is a lot of good historical information in this book and as always Curtis' writing is wonderful. I just wasn't feeling this book however.

I received a copy of this book from Netgalley.

It's really great to read books written for children in which the parents are stable, loving, supportive, and allow the children to be agents of their own story without fully abandoning them!

It's also really great to read a book with two main characters, of different races/ethnicities, where both feel authentic, and the author commands the reader's trust so completely by taking the time to build real empathy for both (parallel) stories. Curtis says he "stumbled across the story of the Irish immigration in Canada" (in the endnote), while doing research for a follow-up to Elijah of Buxton, but his portrayal of Red's family suggests a deeper connection than that.

I think this story would be captivating & mind-expanding for a wide range of young readers, to whom I will happily recommend it, whether or not they've read Elijah of Buxton.

I had a few minor quibbles - I had to read the first chapter (11 pages!) three times to understand that there were a group of boys in 1901 Canada pretending to be soldiers in the American Civil War, as described by one 13-year-old, who was simultaneously including pertinent information about his actual family and his actual goals & personality.

Soon after that, my belief was again suspended when Benji de-constructs & re-constructs upside-down a meticulously crafted tree-house his incredibly talented siblings had created without his permission or knowledge in a part of the woods he felt belonged only to him.

Finally, I got confused about some of the characters' ethnicity, because Red acted (around his grandmother) as if Benji were his first & only black friend, but in fact, he had already described one of his regular friends (Hickman Holmely) as a black person. (p.35) Why hadn't Red ever noticed his discomfort with his grandmother's racism before?

Perhaps the thing I liked best is that Red & Benji are similar in many ways - both of them supremely confident about their intelligence & capabilities, and don't waste much time worrying about other people's points of view until they meet one another, which changes each of them.

I can't help but notice a few other minor missed points, even if they didn't detract from the book for me at all. (1) Benji is so arrogant, he fails to realize that his upside-down project has worsened his initial complaint, because instead of having just 2 siblings traipsing through his woods, he then had hundreds of children. Luckily, before this even registers with him, the situation changes abruptly. (2) The Madman says, "I knowed your ma when she weren't nothing but a babe. I knowed her when she first come to Buxton." (p.100) Later, Benji's mom calls him Uncle Cooter, and he is suddenly treated as a blood relative. Maybe young readers will not be bothered by this, but wouldn't Benji wonder why his blood-relative was kept secret for 13 years, and his family never reached out to him in any way?

Benji's lack of interest in pondering that question is consistent with his character, however, as he demonstrates that he is more interested in composing a headline than in doing an investigation. For this Curtis is ingenious - an adult reader or writer knows why this is significant, but it probably wouldn't matter to young readers, and it probably would be inauthentic to the young character of 1901.

It's also really great to read a book with two main characters, of different races/ethnicities, where both feel authentic, and the author commands the reader's trust so completely by taking the time to build real empathy for both (parallel) stories. Curtis says he "stumbled across the story of the Irish immigration in Canada" (in the endnote), while doing research for a follow-up to Elijah of Buxton, but his portrayal of Red's family suggests a deeper connection than that.

I think this story would be captivating & mind-expanding for a wide range of young readers, to whom I will happily recommend it, whether or not they've read Elijah of Buxton.

I had a few minor quibbles - I had to read the first chapter (11 pages!) three times to understand that there were a group of boys in 1901 Canada pretending to be soldiers in the American Civil War, as described by one 13-year-old, who was simultaneously including pertinent information about his actual family and his actual goals & personality.

Soon after that, my belief was again suspended when Benji de-constructs & re-constructs upside-down a meticulously crafted tree-house his incredibly talented siblings had created without his permission or knowledge in a part of the woods he felt belonged only to him.

Finally, I got confused about some of the characters' ethnicity, because Red acted (around his grandmother) as if Benji were his first & only black friend, but in fact, he had already described one of his regular friends (Hickman Holmely) as a black person. (p.35) Why hadn't Red ever noticed his discomfort with his grandmother's racism before?

Perhaps the thing I liked best is that Red & Benji are similar in many ways - both of them supremely confident about their intelligence & capabilities, and don't waste much time worrying about other people's points of view until they meet one another, which changes each of them.

I can't help but notice a few other minor missed points, even if they didn't detract from the book for me at all. (1) Benji is so arrogant, he fails to realize that his upside-down project has worsened his initial complaint, because instead of having just 2 siblings traipsing through his woods, he then had hundreds of children. Luckily, before this even registers with him, the situation changes abruptly. (2) The Madman says, "I knowed your ma when she weren't nothing but a babe. I knowed her when she first come to Buxton." (p.100) Later, Benji's mom calls him Uncle Cooter, and he is suddenly treated as a blood relative. Maybe young readers will not be bothered by this, but wouldn't Benji wonder why his blood-relative was kept secret for 13 years, and his family never reached out to him in any way?

Benji's lack of interest in pondering that question is consistent with his character, however, as he demonstrates that he is more interested in composing a headline than in doing an investigation. For this Curtis is ingenious - an adult reader or writer knows why this is significant, but it probably wouldn't matter to young readers, and it probably would be inauthentic to the young character of 1901.