Take a photo of a barcode or cover

233 reviews for:

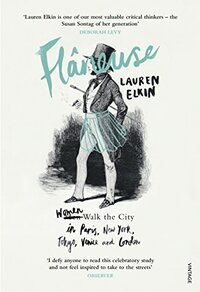

Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London

Lauren Elkin

233 reviews for:

Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London

Lauren Elkin

I am fascinated by flanerie; I had several lectures based around the very act whilst studying at King's College London, and loved every moment of them. I read a couple of good books about streetwalking at the time, and whilst Elkin does repeat a lot of the details from them, I still found Flaneuse engaging and enjoyable. I very much liked the way in which she wove in her own experiences of living and walking in different cities around the world. All in all, it was a splendid volume to read whilst nursing my aching feet after walking around in Amsterdam.

adventurous

challenging

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

Over all it was very enjoyable. Though I was a little irritated by how Elkin didn't write as equally about Tokyo as she did about Paris, London or Venice. That must be her nod to Martha Gellhorn having no patience for objectivity. And the Paris-Protest chapter dragged a little.

1/5: She loves the word FLANEUR and then the female version - FLANEUSE. But historically who were these types, and is there a flaneuse today? She also recalls her youthful struggles to walk the New York suburbs.

2/5: She describes her own walks through London's Bloomsbury, which takes her back to when Virginia Woolf covered the same route, in her life and in her novels.

3/5: She describes Paris, which is THE great walking city. Beneath today's concrete lies cobblestones, which gets her thinking about an earlier age and the remarkable George Sand, who in the 1800's promenaded around in gentleman's clothes.

4/5: She spent time in Venice, researching a novel. And here she recalls the artist Sophie Calle, who came to the city to 'follow' a man called 'Henri B'. All in the name of creativity of course..

5/5: There's an intriguing photograph of 'Jinx Allen', taken in Florence by Ruth Orkin, and it's mysteries are now revealed. Then some reveries after wandering the sidewalks of New York..

Reader Julianna Jennings

Producer Duncan Minshull.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07mwqf9

Lauren Elkin’s Flâneuse (Flâneuse [flanne-euhze], noun, from the French. Feminine form of flâneur [flanne-euhr], an idler, a dawdling observer, usually found in cities, incorporates a lot of different types of writing. It’s part memoir, part biography, part travel writing, part literary criticism, part social history. Basically, it is a book about freedom, women’s freedom to walk, in particular. Which leads us to a simple and old question.

Who ‘owns’ the street? This simple question has been the focus of many a scholarly debate in fields ranging from sociology and gender studies to economics and history. I will not explore here this issue; there are a lot of sources if you want to read more about this. I will just say that historically the men were having more access to the streets of the city than women who were confined to their homes or if they had to go out, their movements were restricted by either the use or a carriage or by being accompanied by a chaperone.

The flâneur is a product of the big European cities of the nineteen century. He usually spent his days wandering the streets of Paris and London, watching the world before his eyes. The flâneur was bourgeois and male. Women, were categorically excluded from “flânerie,” that is the Freedom to wander alone around a city, exploring, having a wonderful time, or just wasting time.

Added to her own story, while walking the cities of Paris, London, Tokyo, Venice and New York, Elkin also tells the stories of the women, who before her, began to claim a space in the city for themselves. Jean Rhys, Virginia Woolf, George Sand, Sophie Calle, Agnès Varda, and Martha Gellhorn, are a few of the female urban walkers in whose footsteps we now trod.

Lauren Elkin is not a flâneuse that just wanders aimlessly in Paris, the city she comes to love. She observes, questions and reflects and then she creates lively, intelligent and rich works, like the Flâneuse.

Who ‘owns’ the street? This simple question has been the focus of many a scholarly debate in fields ranging from sociology and gender studies to economics and history. I will not explore here this issue; there are a lot of sources if you want to read more about this. I will just say that historically the men were having more access to the streets of the city than women who were confined to their homes or if they had to go out, their movements were restricted by either the use or a carriage or by being accompanied by a chaperone.

The flâneur is a product of the big European cities of the nineteen century. He usually spent his days wandering the streets of Paris and London, watching the world before his eyes. The flâneur was bourgeois and male. Women, were categorically excluded from “flânerie,” that is the Freedom to wander alone around a city, exploring, having a wonderful time, or just wasting time.

Added to her own story, while walking the cities of Paris, London, Tokyo, Venice and New York, Elkin also tells the stories of the women, who before her, began to claim a space in the city for themselves. Jean Rhys, Virginia Woolf, George Sand, Sophie Calle, Agnès Varda, and Martha Gellhorn, are a few of the female urban walkers in whose footsteps we now trod.

Lauren Elkin is not a flâneuse that just wanders aimlessly in Paris, the city she comes to love. She observes, questions and reflects and then she creates lively, intelligent and rich works, like the Flâneuse.

Really fascinating and inspiring, but the Tokyo chapter is perfunctory at best and orientalist at worst. Whereas Elkin writes of the other cities with clear passion and adoration, it seems like she is unable to make any effort to find a single female Japanese author, artist, or filmmaker who roamed the streets of Tokyo? Really? Sofia Coppola, who merely uses Tokyo as the strange, foreign backdrop against which her self-absorbed white characters "discover themselves" and does nothing to humanise the city and its inhabitants... Really? A tiny section at the end saying "but oh, at the end I grew to like it." Really? I guess I have to thank Elkin's editor for making her put that in.

adventurous

funny

reflective

relaxing

slow-paced

I guess I thought this would be more historical, but it involved a great deal of memoir-ish content—fine with me, because I love memoirs.

Elkin is a talented and thoughtful writer, weaving together history, personal experience, and these deep insightful close readings of texts or films that made me want to inhale her bibliography. It kind of scratched many of my intellectual itches (women, cities, books, etc) and for that, I think it’ll become a favorite.

Elkin is a talented and thoughtful writer, weaving together history, personal experience, and these deep insightful close readings of texts or films that made me want to inhale her bibliography. It kind of scratched many of my intellectual itches (women, cities, books, etc) and for that, I think it’ll become a favorite.

only read the first half, had to return to library. will def check it out again!

Well-written and researched and, yet, for a book that hit every target market button in me (peripatetic, literature-loving, inveterate walker woman), I wanted to enjoy this read more than I did. I think perhaps it suffered by comparison to Jessa Crispin's excellent The Dead Ladies Project, which I read earlier this year. The books have a lot in common: women wandering around Europe (Elkin also spends time in New York and Tokyo) writing about artists who intrigue them interspersed with memoir. They even cover some of the same ground, namely London and Paris and Jean Rhys, albeit with very different takes. Elkin's chapter on the writer Martha Gellhorn also reminded me of Crispin's on Rebecca West. In short, Flâneuse became for me the square girl's version of Dead Ladies, which I write with the authority of being a square girl myself.

Part of what I mean by "square" has not just to do with what Elkin discloses about herself but that she is an academic, and the writing feels academic in parts. Flâneuse closes with 25 pages of a Bibliography and Notes, testament to what went into the book and the kind of detail you can expect. There are indeed gems in here, but I sometimes felt I had to wade through a lot to find them.

Part of what I mean by "square" has not just to do with what Elkin discloses about herself but that she is an academic, and the writing feels academic in parts. Flâneuse closes with 25 pages of a Bibliography and Notes, testament to what went into the book and the kind of detail you can expect. There are indeed gems in here, but I sometimes felt I had to wade through a lot to find them.