Take a photo of a barcode or cover

163 reviews for:

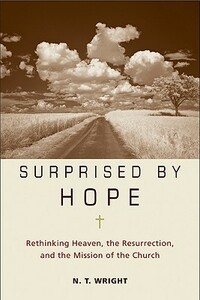

Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church

N.T. Wright

163 reviews for:

Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church

N.T. Wright

NT Wrights conversational style can frustrate at times, but I’m Surprised by Hope he puts forth a clear case for Christian resurrection. What historical evidence points to it, and what scripture says on life after life after death as he puts it. A challenge to the Christian and can clear up misguided ideas in the non Christian. A good read, even if it doesn’t all make sense in my little peanut brain.

This book is brilliant. N.T. Wright is brilliant. I can’t recommend this book highly enough.

slow-paced

I read this on the recommendation of two people whom I respect (who don't know each other). However, I have been puzzled as to why they recommended it throughout my struggle to read (abandoned/DNF) and then listen to this book. I did not find it particularly informative or inspiring. I guess I should give it one star, but I'll leave it at two out of respect for those who made the suggestion. Maybe I'm missing something, or maybe I'm not the intended audience, but my sense is that the book just wasn't that good.

I've got good reasons to want to read this book, but I'm having a terrible time getting through it. Switching to audio edition in hopes that that will help. I'm not sure why I'm having so much difficulty focusing, remembering what I read, etc. Just a real struggle.

This is a wonderful refreshing read from N.T. Wright! Starting from a close reconsideration of the doctrine of the general resurrection as an explicitly embodied concept he moves into an explication of the consequences of remembering orthodoxy elsewhere in eschatology and in the church. He biblical exegesis is rock solid and vintage Wright, and quite readable, oftentimes a distillation of the more technical work in "Resurrection and the Son of God". It does seem that he tries to pack a bit too much into this volume as his ethical reflections in the closing chapters are a bit thin at times. Overall I highly recommend this as a refreshing read and an excellent entry point into re-considering embodiment.

hopeful

informative

challenging

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced

Rediscovering Easter

In this book, Wright shows how the Church's teachings about Christ's resurrection and its meaning for the future have devolved over time to a muddled view of a disembodied, ethereal afterlife. Wright reintroduces the reader to the early church's understanding of Easter and resurrection and how it fits with God's plan for a new heaven and a new earth.

In this book, Wright shows how the Church's teachings about Christ's resurrection and its meaning for the future have devolved over time to a muddled view of a disembodied, ethereal afterlife. Wright reintroduces the reader to the early church's understanding of Easter and resurrection and how it fits with God's plan for a new heaven and a new earth.

Pointed scholarship/practical application

Paradigm shifting in many ways. I found this to be incredibly encouraging and invigorating to my soul. A scholarly, Biblical theology to understanding and practicing the mission of the which in the modern age.

Paradigm shifting in many ways. I found this to be incredibly encouraging and invigorating to my soul. A scholarly, Biblical theology to understanding and practicing the mission of the which in the modern age.

challenging

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced