Take a photo of a barcode or cover

"The most misspent day in any life is the one when you've failed to laugh." - Chamfort

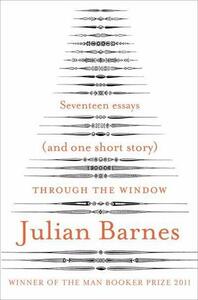

Yesterday I first cracked the cover of this in Frankfort Airport, enjoying espresso as I gazed about at the number of beer drinkers at 9 a.m. on a Sunday. As Julian Barnes notes early, his family didn't go to church but they did go to the library. Finally succumbing to slumber, I crashed without finishing Barnes' second examination of Ford Maddox Ford. Replenished, I awoke today before dawn and was off wandering New Belgrade. Pleasantly winded, I returned and read for a hour in a churchyard waiting for the currency exchange to open. Kipling and France were blended in pair of masterful pieces while I waited. It is now nearly noon here and the author closed the collection with a multifaceted reflections on Updike and literary grieving. My own life appears ripe and expanded at the present.

Yesterday I first cracked the cover of this in Frankfort Airport, enjoying espresso as I gazed about at the number of beer drinkers at 9 a.m. on a Sunday. As Julian Barnes notes early, his family didn't go to church but they did go to the library. Finally succumbing to slumber, I crashed without finishing Barnes' second examination of Ford Maddox Ford. Replenished, I awoke today before dawn and was off wandering New Belgrade. Pleasantly winded, I returned and read for a hour in a churchyard waiting for the currency exchange to open. Kipling and France were blended in pair of masterful pieces while I waited. It is now nearly noon here and the author closed the collection with a multifaceted reflections on Updike and literary grieving. My own life appears ripe and expanded at the present.

Upon immediately finishing this book last night, I'd decided to write only a succinct review, something like:

'I enjoyed this collection of essays, even the ones about authors I'd never heard of (i.e., all the French ones excluding Flaubert) and of books I haven't read (e.g. [b:Parade's End|777824|Parade's End|Ford Madox Ford|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1450231478s/777824.jpg|2244425]). Even without having read Hemingway's [b:Homage to Switzerland|18741518|Homage to Switzerland|Ernest Hemingway|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1383141306s/18741518.jpg|26620700], I perceived and appreciated the layers in the one short story included here.'

The End

Instead I had trouble sleeping while sentences flowed through my head, as they did the night before when I'd finished reading Barnes' critique of Lydia Davis' translation of [b:Madame Bovary|2175|Madame Bovary|Gustave Flaubert|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1335676143s/2175.jpg|2766347]. (My dreamed-sentences that night kept ending inexplicably on the word 'Spain.') This all reminded me of how I felt while reading [b:The Sense of an Ending|10746542|The Sense of an Ending|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1311704453s/10746542.jpg|15657664] and how just about anything I read of Barnes gets to me like this, even apparently his nonfiction here that elucidates by placing the reviewed author in his own time period clearly and without pseudo-academic jargon (reminding me of the main character in the short story who mentions that he is not an academic, though he is teaching). I also enjoyed reading of the tensions between English and French literature.

The ending of that short story, "Homage to Hemingway," had me paging backwards, a sure sign of a good story for me, as I realized why Barnes used a certain technique, thus another layer. The story also includes the theme of not judging a work based on biography, which leads to a thought on the last essay: Though nowhere in his review of Oates' [b:A Widow's Story|8703772|A Widow's Story|Joyce Carol Oates|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1288782203s/8703772.jpg|9989353] does he mention his own loss, anyone who knows of his wife's death will know where his empathy comes from and will feel for him.

As I said of [b:The Pedant in the Kitchen|45371|The Pedant In The Kitchen|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1447155503s/45371.jpg|2122450], I'd read his grocery list.

'I enjoyed this collection of essays, even the ones about authors I'd never heard of (i.e., all the French ones excluding Flaubert) and of books I haven't read (e.g. [b:Parade's End|777824|Parade's End|Ford Madox Ford|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1450231478s/777824.jpg|2244425]). Even without having read Hemingway's [b:Homage to Switzerland|18741518|Homage to Switzerland|Ernest Hemingway|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1383141306s/18741518.jpg|26620700], I perceived and appreciated the layers in the one short story included here.'

The End

Instead I had trouble sleeping while sentences flowed through my head, as they did the night before when I'd finished reading Barnes' critique of Lydia Davis' translation of [b:Madame Bovary|2175|Madame Bovary|Gustave Flaubert|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1335676143s/2175.jpg|2766347]. (My dreamed-sentences that night kept ending inexplicably on the word 'Spain.') This all reminded me of how I felt while reading [b:The Sense of an Ending|10746542|The Sense of an Ending|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1311704453s/10746542.jpg|15657664] and how just about anything I read of Barnes gets to me like this, even apparently his nonfiction here that elucidates by placing the reviewed author in his own time period clearly and without pseudo-academic jargon (reminding me of the main character in the short story who mentions that he is not an academic, though he is teaching). I also enjoyed reading of the tensions between English and French literature.

The ending of that short story, "Homage to Hemingway," had me paging backwards, a sure sign of a good story for me, as I realized why Barnes used a certain technique, thus another layer. The story also includes the theme of not judging a work based on biography, which leads to a thought on the last essay: Though nowhere in his review of Oates' [b:A Widow's Story|8703772|A Widow's Story|Joyce Carol Oates|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1288782203s/8703772.jpg|9989353] does he mention his own loss, anyone who knows of his wife's death will know where his empathy comes from and will feel for him.

As I said of [b:The Pedant in the Kitchen|45371|The Pedant In The Kitchen|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1447155503s/45371.jpg|2122450], I'd read his grocery list.

Life and reading are not separate activities. When you read a great book, you don't escape from life, you plunge deeper into it.

When I asked my daughter this weekend to make a collage out of the portraits I collected from the writers discussed in this compilation of essays, she rolled her eyes sceptically when she found out I had been reading a book on books, which she took as a symptom her mother has entered another more dangerous stage in her book craziness. Reading books on books, isn’t that just horror incarnate, a terribly nerdy thing to do? Asking why I still didn’t post her work of art (on which she secretly was a little proud), sulking when I disclosed my struggling to word my impressions, she sighed and brazenly summoned me to stop trying and keep it simple: ‘Just say “This is a brilliant book. Highly recommended!” (And please cook dinner mother, now).

By analysing and reflecting on the writing and lives of 5 British, 6 American and 5 French writers, Julian Barnes shares his insights on how fiction works, and why, and rather unsurprisingly to me he turns out not only a stunning fiction writer but also a clever and perceptive reader, maybe the kind of reader which many writers dreams of, an ideal and benevolent reader, considering that in his opinion ‘Reading is a majority skill but a minority art’. A reader who phrases his ruminations on books in an erudite, thoughtful, incisive and witty style, mostly in a mild and sympathetic voice, enlivening his exposé on readers and writers with more juicy or entertaining biographical anecdotes or characterisations – in short, a fellow writer, knowing the secrets of writerly craftsmanship and psychology. While his affection for some of the authors is palpable and infectious (Fitzgerald, Wharton, Ford), others get a more ironic, reserved and ambivalent handling (Orwell, Houellebecq).

One could wonder if it is actually meaningful to read about an author or book one hasn’t read yet, but while at first determined to read only the essays on authors I had at least read a short story of (Penelope Fitzgerald, Orwell, Ford Madox Ford, Chamfort, Flaubert, Houellebecq, Mérimée, Updike, Kipling), in my eagerness and enthusiasm I couldn’t stop myself greedily devouring the whole chocolate box, even the essays on authors entirely obscure to me (Arthur Clough, Félix Féneon, Lorrie Moore) or haven’t yet read anything by (Edith Wharton, Joan Didion, Joyce Oates), taking a singular delight in Barnes’s short story Homage to Hemingway, which is playfully modelled on Hemingway’s story [b:Homage to Switzerland|18741518|Homage to Switzerland|Ernest Hemingway|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1383141306s/18741518.jpg|26620700] and uses its structure to reflect and comment on Hemingway as a writer in a gently metafictional way.

Besides encountering Barnes’s typical ingredients dispersed throughout the essays (Flaubertophilia, Francophilia), part of the pleasure is that apart from the light Barnes casts on the fiction and authors he discusses, he also obliquely or more directly reveals some of his own preferential techniques as a writer. When talking about unreliable narrators with Ford (‘the novel plays with the reader as it reveals and conceals truth’, ‘Ford plays relentlessly on the reader’s desire to trust the narrative’), or when extolling Ford’s [b:The Good Soldier|7628|The Good Soldier|Ford Madox Ford|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1389213508s/7628.jpg|1881188] for ‘its immaculate use of a ditheringly unreliable narrator, it sophisticated disguise of true narrative behind a false façade of apparent narrative, its self-reflectingness, its deep duality about human motive, intention and experience' – which all sounds pretty programmatic for his own novel [b:The Sense of an Ending|10746542|The Sense of an Ending|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1311704453s/10746542.jpg|15657664].

Some of his sentences proved quite persistent, popping up in my head again when pondering on friend’s reviews, having to restrain myself from bombarding friends with quotations from this book (‘you marry to continue the conversation'), this sticky effect enforced as they kindled memories on some of his novels, especially the poignant closing essay ‘Regulating sorrow’ on the accounts of bereavement from Joan Didion and Joyce Carol Oates, of which some thoughts return in the last chapter of his later novel [b:Levels of Life|17262198|Levels of Life|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1363837006s/17262198.jpg|23694714] - like the unsolicited advice given to a widowed person ‘Foreign travel is advised; so is getting a dog’, or the closing lines of this collection, an excerpt from a letter of consolation by Dr. Johnson on what to expect when mourning one’s wife, which also elucidates the way Barnes as a writer and person is affected and influenced by his reading like his reader in turn is by reading Barnes:

“He that outlives a wife whom he has long loved, sees himself disjoined from the only mind that has the same hopes, and fears, and interests; from the only companion with whom he has shared much good or evil; and with whom he could set his mind his mind at liberty, to retrace the past, or anticipate the future. The continuity of being is lacerated; the settle course of sentiment and action is stopped; and life stands suspended and motionless, till it is driven by external causes into a new channel. But the time of suspense is dreadful.”

As a bonus, there is the fun smuggled into the index (not in the Dutch edition) – Barnes began his writing life as an OED lexicographer in what he called the "sports and dirty words department" and ça se voit:

Ford Madox Ford – compared to a poached egg;

Sex – danger of Belgians; in exchange for an interview?; post-coital harness- mending; post-coital melon-eating;

Wildlife – George Orwell ‘not a parrot’; FM Ford as great auk ; Tietjens compared to entire farmyard; also to lobster; vile thoughts about kittens

The Dutch edition, which was published before the English one, while lacking the playful index, comprises as a consolation prize a lovely additional essay on Barnes’s bibliophilism, which was published separately as a pamphlet [b:A Life with Books|15735364|A Life with Books|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1342186419s/15735364.jpg|21418162] to celebrate Independent Booksellers week and which also can be read here.

Alone, and yet in company: that is the paradoxical position of the reader. Alone in the company of a writer who speaks in silence of your mind. And – a further paradox – it makes no difference whether that writer is alive or dead.

A GR friend writes on his profile he prefers his authors dead. This might come across as a somewhat provocatively articulated statement and however I wouldn’t venture to phrase it that boldly, I can relate to it, as most of my favourite authors simply are dead, even if they seem very much present and alive to me when reading them. Although I have only read 4 of his novels so far and not so often read still flourishing authors, by reading this collection of essays it occurred to me that Julian Barnes might have grown into my favourite living author at the moment – and that I am far of alone in adoring his writing. It amuses me to notice a similar keenness with some friends – writing in their reviews that to them Barnes simply can do no wrong, or that they feel smarter by reading him, that they’d read his grocery list, or feel so at ease in his company. Admitting my own almost fangirlish admiration might have gotten in the way of writing a proper review, I blushingly and cheerfully apologize and make it up by referring to the plentiful fine reviews written on this book here, of which Helle's was the one that kindly pointed me to it.

A multifaceted gem and an awesome source of inspiration for further reading., guiding me both into exploring unknown territory as well as enlightening previously roamed paths.

Collage of photos created by Senta - thanks a ton, dearest daughter!

When I asked my daughter this weekend to make a collage out of the portraits I collected from the writers discussed in this compilation of essays, she rolled her eyes sceptically when she found out I had been reading a book on books, which she took as a symptom her mother has entered another more dangerous stage in her book craziness. Reading books on books, isn’t that just horror incarnate, a terribly nerdy thing to do? Asking why I still didn’t post her work of art (on which she secretly was a little proud), sulking when I disclosed my struggling to word my impressions, she sighed and brazenly summoned me to stop trying and keep it simple: ‘Just say “This is a brilliant book. Highly recommended!” (And please cook dinner mother, now).

By analysing and reflecting on the writing and lives of 5 British, 6 American and 5 French writers, Julian Barnes shares his insights on how fiction works, and why, and rather unsurprisingly to me he turns out not only a stunning fiction writer but also a clever and perceptive reader, maybe the kind of reader which many writers dreams of, an ideal and benevolent reader, considering that in his opinion ‘Reading is a majority skill but a minority art’. A reader who phrases his ruminations on books in an erudite, thoughtful, incisive and witty style, mostly in a mild and sympathetic voice, enlivening his exposé on readers and writers with more juicy or entertaining biographical anecdotes or characterisations – in short, a fellow writer, knowing the secrets of writerly craftsmanship and psychology. While his affection for some of the authors is palpable and infectious (Fitzgerald, Wharton, Ford), others get a more ironic, reserved and ambivalent handling (Orwell, Houellebecq).

One could wonder if it is actually meaningful to read about an author or book one hasn’t read yet, but while at first determined to read only the essays on authors I had at least read a short story of (Penelope Fitzgerald, Orwell, Ford Madox Ford, Chamfort, Flaubert, Houellebecq, Mérimée, Updike, Kipling), in my eagerness and enthusiasm I couldn’t stop myself greedily devouring the whole chocolate box, even the essays on authors entirely obscure to me (Arthur Clough, Félix Féneon, Lorrie Moore) or haven’t yet read anything by (Edith Wharton, Joan Didion, Joyce Oates), taking a singular delight in Barnes’s short story Homage to Hemingway, which is playfully modelled on Hemingway’s story [b:Homage to Switzerland|18741518|Homage to Switzerland|Ernest Hemingway|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1383141306s/18741518.jpg|26620700] and uses its structure to reflect and comment on Hemingway as a writer in a gently metafictional way.

Besides encountering Barnes’s typical ingredients dispersed throughout the essays (Flaubertophilia, Francophilia), part of the pleasure is that apart from the light Barnes casts on the fiction and authors he discusses, he also obliquely or more directly reveals some of his own preferential techniques as a writer. When talking about unreliable narrators with Ford (‘the novel plays with the reader as it reveals and conceals truth’, ‘Ford plays relentlessly on the reader’s desire to trust the narrative’), or when extolling Ford’s [b:The Good Soldier|7628|The Good Soldier|Ford Madox Ford|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1389213508s/7628.jpg|1881188] for ‘its immaculate use of a ditheringly unreliable narrator, it sophisticated disguise of true narrative behind a false façade of apparent narrative, its self-reflectingness, its deep duality about human motive, intention and experience' – which all sounds pretty programmatic for his own novel [b:The Sense of an Ending|10746542|The Sense of an Ending|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1311704453s/10746542.jpg|15657664].

Some of his sentences proved quite persistent, popping up in my head again when pondering on friend’s reviews, having to restrain myself from bombarding friends with quotations from this book (‘you marry to continue the conversation'), this sticky effect enforced as they kindled memories on some of his novels, especially the poignant closing essay ‘Regulating sorrow’ on the accounts of bereavement from Joan Didion and Joyce Carol Oates, of which some thoughts return in the last chapter of his later novel [b:Levels of Life|17262198|Levels of Life|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1363837006s/17262198.jpg|23694714] - like the unsolicited advice given to a widowed person ‘Foreign travel is advised; so is getting a dog’, or the closing lines of this collection, an excerpt from a letter of consolation by Dr. Johnson on what to expect when mourning one’s wife, which also elucidates the way Barnes as a writer and person is affected and influenced by his reading like his reader in turn is by reading Barnes:

“He that outlives a wife whom he has long loved, sees himself disjoined from the only mind that has the same hopes, and fears, and interests; from the only companion with whom he has shared much good or evil; and with whom he could set his mind his mind at liberty, to retrace the past, or anticipate the future. The continuity of being is lacerated; the settle course of sentiment and action is stopped; and life stands suspended and motionless, till it is driven by external causes into a new channel. But the time of suspense is dreadful.”

As a bonus, there is the fun smuggled into the index (not in the Dutch edition) – Barnes began his writing life as an OED lexicographer in what he called the "sports and dirty words department" and ça se voit:

Ford Madox Ford – compared to a poached egg;

Sex – danger of Belgians; in exchange for an interview?; post-coital harness- mending; post-coital melon-eating;

Wildlife – George Orwell ‘not a parrot’; FM Ford as great auk ; Tietjens compared to entire farmyard; also to lobster; vile thoughts about kittens

The Dutch edition, which was published before the English one, while lacking the playful index, comprises as a consolation prize a lovely additional essay on Barnes’s bibliophilism, which was published separately as a pamphlet [b:A Life with Books|15735364|A Life with Books|Julian Barnes|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1342186419s/15735364.jpg|21418162] to celebrate Independent Booksellers week and which also can be read here.

Alone, and yet in company: that is the paradoxical position of the reader. Alone in the company of a writer who speaks in silence of your mind. And – a further paradox – it makes no difference whether that writer is alive or dead.

A GR friend writes on his profile he prefers his authors dead. This might come across as a somewhat provocatively articulated statement and however I wouldn’t venture to phrase it that boldly, I can relate to it, as most of my favourite authors simply are dead, even if they seem very much present and alive to me when reading them. Although I have only read 4 of his novels so far and not so often read still flourishing authors, by reading this collection of essays it occurred to me that Julian Barnes might have grown into my favourite living author at the moment – and that I am far of alone in adoring his writing. It amuses me to notice a similar keenness with some friends – writing in their reviews that to them Barnes simply can do no wrong, or that they feel smarter by reading him, that they’d read his grocery list, or feel so at ease in his company. Admitting my own almost fangirlish admiration might have gotten in the way of writing a proper review, I blushingly and cheerfully apologize and make it up by referring to the plentiful fine reviews written on this book here, of which Helle's was the one that kindly pointed me to it.

A multifaceted gem and an awesome source of inspiration for further reading., guiding me both into exploring unknown territory as well as enlightening previously roamed paths.

Collage of photos created by Senta - thanks a ton, dearest daughter!

Collection of essays on writers and literature, published in the period 1996-2011. Barnes is an attentive reader, that's not at all surprising. His analysis mainly is literary-technical, but some essays contain salient information that was not yet known to me. Such as the important role that Rudyard Kipling played in the British War Graves Commission after the First World War, a result of the death of his 18-year-old son in the trenches. And authors like Lornie Morre or Penelope Fitzgerald were completely unknown to me. A nice illustration of the great imaginative power and aesthetic delight of fiction.

Barnes can write not only terrific fiction but also terrific essay so literature. I thoroughly enjoyed this collection of essays and learned much from it.

Every author Barnes writes about induces the desire to read that author. I think the great literary criticism all comes down to this: sparking further curiosity and wanting.

- Fiction, more than any other written form, explains and expands life.

- We are, in our deepest selves, narrative animals; also, seekers of answers. The best fiction rarely provides answers; but it does formulate the questions exceptionally well.

* On Penelope Fitzgerald

One her earlier novels

- They are adroit, odd, highly pleasurable, but modest in ambition.

- Many writers start by inventing away from their lives, and then, when their material runs out, turn back to more familiar sources. Fitzgerald did the opposite, and by writing away from her own life she liberated herself into greatness.

- Her writing had to be fitted into the occasional breathing spaces left by family life; and she made little money until the late success of The Blue Flower in America.

- "You should write... novels about human beings who you think are sadly mistaken." Fitzgerald is tender towards her characters and their worlds, unpredictably funny, and at times surprisingly aphoristic; though it is characteristic of her that such moments of wisdom appear not author-generated, but arising in the text organically, like moss or coral. Her fictional personnel are rarely vicious or deliberately evil; when things go wrong for them, or when they inflict harm on others, it is usually out of misplaced understanding, a lack less of sympathy than of imagination.

- How does she convey what she knows in such a compact, exact, dynamic and resonant way?

- Mastery of sources and a state for concision might lead you to expect that the narrative line of Fitzgerald's novels would be pre-eminently lucid. Far from it: there is a kind of benign wrong-footingness at work, often from the first line.

------------------

- Such divergences transfer into their poetry. Arnold comes out of Keatsian Romanticism, Clough out of Byronism - specifically, the sceptical, worldly, witty tone-mixing of Don Juan.

---------------

juxtaposing opposing ideas together

- For the next thirty years, the debate continued as to the true nature of the Wilkeses - diligent pedagogues or manipulative sadists - and as to the wider consequences of sending small boys away from home at the age of eight: character-building or character-deforming?

- 'Such, Such' retains immense force, its clarity of exposition matched by its animating rage. Orwell does not try to backdate his understanding; he retains the inchoate emotional responses of the young Eric Blair to the system into which he had been flung. But now, as George Orwell, he is in a position to anatomise the economic and class infrastructure of St. Cyprian's, and those hierarchies of power which the pupil would later meet in grown-up, public, political form: in this respect such schools were trully named 'preparatory'.

- Orwell is profoundly English in even more ways than these. He is deeply untheoretical and wary of general conclusions that do not come from specific experiences.

- On the one hand there are change-of-heart people, who believe that if you improve human nature, all the problems of society will fall away; and on the other social engineers, who believe that once you fix society - make it fairer, more democratic, less divided - then the problems of human nature will fall away.

To read:

Ford's The Good Soldier

Houellebecq's Atomized

Wharton's The Reef

Geniusness of Kipling

See how he begins the essays, his first paragraphs.

Every author Barnes writes about induces the desire to read that author. I think the great literary criticism all comes down to this: sparking further curiosity and wanting.

- Fiction, more than any other written form, explains and expands life.

- We are, in our deepest selves, narrative animals; also, seekers of answers. The best fiction rarely provides answers; but it does formulate the questions exceptionally well.

* On Penelope Fitzgerald

One her earlier novels

- They are adroit, odd, highly pleasurable, but modest in ambition.

- Many writers start by inventing away from their lives, and then, when their material runs out, turn back to more familiar sources. Fitzgerald did the opposite, and by writing away from her own life she liberated herself into greatness.

- Her writing had to be fitted into the occasional breathing spaces left by family life; and she made little money until the late success of The Blue Flower in America.

- "You should write... novels about human beings who you think are sadly mistaken." Fitzgerald is tender towards her characters and their worlds, unpredictably funny, and at times surprisingly aphoristic; though it is characteristic of her that such moments of wisdom appear not author-generated, but arising in the text organically, like moss or coral. Her fictional personnel are rarely vicious or deliberately evil; when things go wrong for them, or when they inflict harm on others, it is usually out of misplaced understanding, a lack less of sympathy than of imagination.

- How does she convey what she knows in such a compact, exact, dynamic and resonant way?

- Mastery of sources and a state for concision might lead you to expect that the narrative line of Fitzgerald's novels would be pre-eminently lucid. Far from it: there is a kind of benign wrong-footingness at work, often from the first line.

------------------

- Such divergences transfer into their poetry. Arnold comes out of Keatsian Romanticism, Clough out of Byronism - specifically, the sceptical, worldly, witty tone-mixing of Don Juan.

---------------

juxtaposing opposing ideas together

- For the next thirty years, the debate continued as to the true nature of the Wilkeses - diligent pedagogues or manipulative sadists - and as to the wider consequences of sending small boys away from home at the age of eight: character-building or character-deforming?

- 'Such, Such' retains immense force, its clarity of exposition matched by its animating rage. Orwell does not try to backdate his understanding; he retains the inchoate emotional responses of the young Eric Blair to the system into which he had been flung. But now, as George Orwell, he is in a position to anatomise the economic and class infrastructure of St. Cyprian's, and those hierarchies of power which the pupil would later meet in grown-up, public, political form: in this respect such schools were trully named 'preparatory'.

- Orwell is profoundly English in even more ways than these. He is deeply untheoretical and wary of general conclusions that do not come from specific experiences.

- On the one hand there are change-of-heart people, who believe that if you improve human nature, all the problems of society will fall away; and on the other social engineers, who believe that once you fix society - make it fairer, more democratic, less divided - then the problems of human nature will fall away.

To read:

Ford's The Good Soldier

Houellebecq's Atomized

Wharton's The Reef

Geniusness of Kipling

See how he begins the essays, his first paragraphs.

informative

reflective

medium-paced

Very good and interesting writing on different amazing authors that maybe are not that popular.

A really well narrated set of witty essays with an entertaining short story tossed in for good measure. All centre around a literary theme and tend to talk about one particular author. Each essay takes a tangential approach to the author's life and work. Many of the authors were unknown to me. Many are French or spent time in France. Rudyard Kipling, for example, spent quite a bit of time in France after his son was killed in WWI. He kept a detailed journal of that time, he was inspecting war cemeteries to ensure their upkeep. Gives an insight to the man and his later work.

The short story centres around a creative writing teacher and his adult students, reminded me a lot of Brian Bilston's poetry in the Pub in "Diary of a Somebody" (listened to that on audio earlier in the year, another I'd recommend).

Looking forward to reading one of Julian Barnes' novels, hopefully later in the year.

The short story centres around a creative writing teacher and his adult students, reminded me a lot of Brian Bilston's poetry in the Pub in "Diary of a Somebody" (listened to that on audio earlier in the year, another I'd recommend).

Looking forward to reading one of Julian Barnes' novels, hopefully later in the year.

"Als je een goed boek leest, ontsnap je niet aan het leven, je stort je er juist dieper in. Er kan sprake zijn van een oppervlakkige ontsnapping – in verschillende landen, mores, spraakpatronen – maar wat je in wezen doet is je begrip versterken van de subtiliteiten, paradoxen, vreugde, pijn en waarheden van het leven. Leven en lezen zijn geen onderscheiden maar symbiotische waarden."

meer: http://winterlief.blogspot.nl/2013/01/gelezen-10.html

meer: http://winterlief.blogspot.nl/2013/01/gelezen-10.html