Scan barcode

xxpriscillaxuxx's review against another edition

informative

tense

slow-paced

3.75

As a complete film beginners. This one is very hard to grasp. It took le full 7 hours to build mental models for this book. But I think it was quite worth it

rowievdvliet's review against another edition

3.0

3,5 stars

Story will teach all writers to do better, not just screenwriters. It analyses the craft in great detail. It will teach you to be as specific as possible and what terms like three-dimensional characters actually mean.

Having said that the book is really dense because it's stuffed with infornation. It's all interesting but I had to take breaks reading it to let everything sink in.

Another thing was really interesting to me. I really feel like Robert McKee knows what he's talking about and he is a good teacher. I could follow and agree with his teachings. And then it would cut to his examples of great films and pieces of screenplays. Mind you, some films I haven't seen or even heard of.

But I really didn't understand why this character from Casablanca carried a different emotion in every bit of dialogue (that's how it read to me). And it felt a bit uncomfortable to read a book full of praise with films about sisters practising incest and others that I perceived as sexual fantasies of white cis man. I would have liked to see more diversity in the films highlighted (although it did use examples I like like Star Wars). I don't think this book needs only examples of diverse films. It was just a weird reading experience to agree with his teachings and then dislike to examples the writer seems to think are some of the best out there.

But if you can see past that (or have a different taste in stories than I do) this is a book that will benefit any writer. I'm glad I have this in my toolkit so I can keep coming back to it to work on my own craft. Even if I never end up writing a screenplay.

Story will teach all writers to do better, not just screenwriters. It analyses the craft in great detail. It will teach you to be as specific as possible and what terms like three-dimensional characters actually mean.

Having said that the book is really dense because it's stuffed with infornation. It's all interesting but I had to take breaks reading it to let everything sink in.

Another thing was really interesting to me. I really feel like Robert McKee knows what he's talking about and he is a good teacher. I could follow and agree with his teachings. And then it would cut to his examples of great films and pieces of screenplays. Mind you, some films I haven't seen or even heard of.

But I really didn't understand why this character from Casablanca carried a different emotion in every bit of dialogue (that's how it read to me). And it felt a bit uncomfortable to read a book full of praise with films about sisters practising incest and others that I perceived as sexual fantasies of white cis man. I would have liked to see more diversity in the films highlighted (although it did use examples I like like Star Wars). I don't think this book needs only examples of diverse films. It was just a weird reading experience to agree with his teachings and then dislike to examples the writer seems to think are some of the best out there.

But if you can see past that (or have a different taste in stories than I do) this is a book that will benefit any writer. I'm glad I have this in my toolkit so I can keep coming back to it to work on my own craft. Even if I never end up writing a screenplay.

nickanderson's review against another edition

5.0

Not much more can be said about this book than already has - its awesome, I loved it, and I learned a lot.

hammo's review against another edition

2.0

Charlie Kaufman gave Story a fair treatment in Adaptation. It's much like a bloated whale carcass: stinky and full of hot air. But if you're willing to hold your breath and dig around, there is some valuable ambergris you can extract. It's not worth reading the whole thing, but it may be worth skimming.

"The art of story is not about the middle ground, but about the pendulum of existence swinging to the limits, about life lived in its most intense states."

"the protagonist must be empathetic [identifiable/relatable]; he may or may not be sympathetic [likeable]."

The cast of characters should be like a solar system around the protagonist. Each support character is designed to illuminate a particular aspect of the hero's personality.

"A subplot may be used to contradict the Controlling Ida of the Central Plot and thus enrich the film with irony."

"Subplots may be used to resonate the Controlling Idea of the Central Plot and enrich the film with variations on a theme."

"To tell a story is to make a promise: If you give me your concentration, I'll give you surprise followed by the pleasure of discovering life, its pains and joys, at levels and in directions you have never imagined."

Scene analysis:

- Define conflict (what does the protagonist want and what's in their way?)

- What value is at stake? (freedom, justice, etc)

- What are the beats? (Pleading, ignoring the plea, threatening, counter-threatening...)

- What is the value delta? (More value? Less value? Same value?)

- Identify the turning point (where the value change occurs)

"A story must build to a final action beyond which the audience cannot imagine another."

"Within unity we must induce as much variety as possible."

"The gracious storyteller makes love to us. He knows we're capable of a tremendous release... if he paces us to it."

"Like symbolism, to point at irony destroys it. Irony must be coolly, casually released with a seeingly innocent unawareness of the effect it's creating and a faith that the audience will get it."

How to progress a story, quoted from this summary:

- social progression: we open up to a small number of characters, and the action leads to widening the field to integrate new ones

- personal progression: opening up to a personal or internal conflict, then progressing towards psychological, moral, emotional complications

- symbolic progression: going from the particular to the universal, from the specific to the archetypal, from the insignificant to the symbolic

- the ironic progression: the character arrives right where he did not want to go, or moves away from the goal he was doing everything to reach

Examples of ironic progression:

- He gets at last what he's always wanted... but to late to have it.

- He's pushed further and further from his goal... only to discover that in fact he's been led right to it.

- He throws away what he later finds is indispensable to his happiness.

- To reach a goal he unwittingly takes the precise steps necessary to lead him away.

- The action he takes to destroy something becomes exactly what are needed to be destroyed by it.

- He comes into possession of something he's certain will make him miserable, does everything possible to get rid of it... only to discover it's the gift of happiness.

From the same summary as above: how to deal with a value theme

- choose a value – for example Justice

- then find it a contrary value – for example Injustice

- then a contradictory value – for example Illegality

- then a negation of the negation – for example Tyranny

Scenes can be linked by what they have in common or what they have in opposition.

William Goldman: "give the audience what it wants, but not the way it expects".

"The life story of each and every character offers encyclopedic possibilities. The mark of a master is to select only a few moments but give us a lifetime."

The ontollogy of story:

- Story values are universally salient parts of human experience which can change from positive to negative over time

- Story events are changes in value achieved through conflict

- A scene is an action through conflict in more or less contiguous space and time. Ideally a scene is also a story event.

- "A beat is an exchange of behaviour in action/reaction."

- "A sequence is a series of scenes - generally two to five - that culminates in a greater impact than any previous scene."

- "An act is a series of sequences that peaks in a climactic scene which causes a major reversal of values, more powerful in its impact than any previous sequence or scene".

- "A story is a series of acts that build to a last act climax or story climax which brings about absolute and irreversible changes."

Story dichotomies:

- Open vs closed ending: are we left with any unanswered questions or unfulfilled emotions?

- Internal vs external conflict

- Single vs multiple protagonists

- Active vs passive protagonist(s)

- Linear vs nonlinear time

- A causality vs coincidence led chain of events

- Consistent vs inconsistent realities (inconsistent realities jump between modes)

McKee even has a story triangle:

"The first step towards a well-told story is to create a small, knowable world. Artists by nature crave freedom, so the principle that the structure/setting relationship restricts creative hoices may stir the rebel in you."

Subgenres of horror:

- Uncanny: scary but rational

- Supernatural: scary and irrational

- Super-uncanny: you have to keep guessing whether it's rational or not

Some other interseting plots:

- Punitive plot: good guy goes bad and is punished

- Education plot: protagonist learns something about life

- Disillusionment plot: protagonist learns something bad about life

- Testing plot: the protagonist is tested

"To anticipate the anticipations of the audience you must master your genre and its conventions."

Characterization is the surface-observable aspects of the character. Deep Character is the stuff that's only revealed in dilemmas and crises.

Good writing not only reveals true character, but also changes the true character over the character arc.

The story should be designed to reveal and change the true character of the protagonist.

"In life, moments that blaze with a fusion of idea and emotion are so rare, when they happen you think you're having a religious experience."

"A CONTROLLING IDEA may be expressed in a single sentence describing how and why life undergoes change from one condition of existence at the beginning to another at the end."

Allegedly, a story should progress through not just the positive value at stake and its negation, but also a contrary value and a negation of the negation:

An interesting kind of rule:

Some types of relationship with audience:

- Mystery: the characters know more than the audience

- Closed mystery: murder happens off-stage and the question is: whodunnit?

- Open mystery: audience sees the murder and the question is: will they get away with it?

- Suspense: the characters and the audience know the same amount

- Dramatic irony: the audience knows more than the characters

If you use coincidence to fix the character's problems, then that's Deus Ex Machina which is bad. So the characters should overcome coincidences, not be rescued by them.

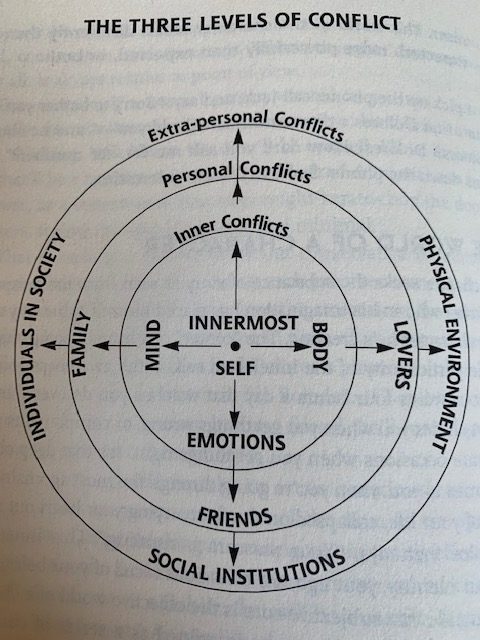

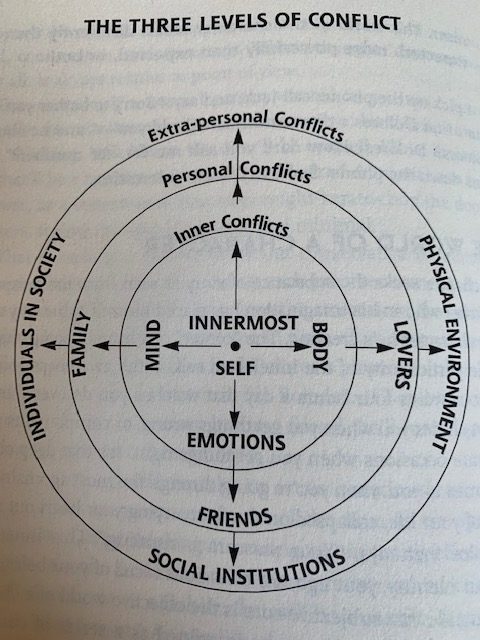

The strengths of each medium:

- Written prose does internal conflict best by zooming into someone's thoughts

- Theatre does personal conflict best by conveying the live nuances of voice and having license to speak unrealistically

- Cinema does extra-personal conflict best by showing big scenes and big props

The more "pure" a novel or play - the more it is dominated by internal or personal conflict - the harder it will be to adapt to cinema

"Everything I learned about human nature I learned from me" - Anton Checkov

Screen dialogue is essentially stikomythia, or a succession of short speeches. After each speech, get a reaction from the interlocutor, creating a series of action-reactions. This can also mean the character reacting to themself.

"Suspense sentences": the meaning of the sentence isn't revealed until the last word. Eg "If you didn't want me to do it, why'd you give me that..." (look? gun? kiss?)

External imagery has symbolic meaning outside the film, internal imagery only has meaning inside the film.

The dimensionality of a character is the amount of contradiction in the character.

The audience is drawn to identifying with the "Center of Good"

"Economy is key and brevity takes time"

Strong characters have both conscious and unconscious desires.

"Obligatory scene": a scene which the audience intuitively knows must eventually happen to bring everything together, such as a showdown between the hero and the villian.

"Major dramatic question": what's the central problem which needs solving?

More weird diagrams:

The second one shows the inciting incident as a shift from the status quo equilibrium.

Portrait of an artist:

"The art of story is not about the middle ground, but about the pendulum of existence swinging to the limits, about life lived in its most intense states."

"the protagonist must be empathetic [identifiable/relatable]; he may or may not be sympathetic [likeable]."

The cast of characters should be like a solar system around the protagonist. Each support character is designed to illuminate a particular aspect of the hero's personality.

"A subplot may be used to contradict the Controlling Ida of the Central Plot and thus enrich the film with irony."

"Subplots may be used to resonate the Controlling Idea of the Central Plot and enrich the film with variations on a theme."

"To tell a story is to make a promise: If you give me your concentration, I'll give you surprise followed by the pleasure of discovering life, its pains and joys, at levels and in directions you have never imagined."

Scene analysis:

- Define conflict (what does the protagonist want and what's in their way?)

- What value is at stake? (freedom, justice, etc)

- What are the beats? (Pleading, ignoring the plea, threatening, counter-threatening...)

- What is the value delta? (More value? Less value? Same value?)

- Identify the turning point (where the value change occurs)

"A story must build to a final action beyond which the audience cannot imagine another."

"Within unity we must induce as much variety as possible."

"The gracious storyteller makes love to us. He knows we're capable of a tremendous release... if he paces us to it."

"Like symbolism, to point at irony destroys it. Irony must be coolly, casually released with a seeingly innocent unawareness of the effect it's creating and a faith that the audience will get it."

How to progress a story, quoted from this summary:

- social progression: we open up to a small number of characters, and the action leads to widening the field to integrate new ones

- personal progression: opening up to a personal or internal conflict, then progressing towards psychological, moral, emotional complications

- symbolic progression: going from the particular to the universal, from the specific to the archetypal, from the insignificant to the symbolic

- the ironic progression: the character arrives right where he did not want to go, or moves away from the goal he was doing everything to reach

Examples of ironic progression:

- He gets at last what he's always wanted... but to late to have it.

- He's pushed further and further from his goal... only to discover that in fact he's been led right to it.

- He throws away what he later finds is indispensable to his happiness.

- To reach a goal he unwittingly takes the precise steps necessary to lead him away.

- The action he takes to destroy something becomes exactly what are needed to be destroyed by it.

- He comes into possession of something he's certain will make him miserable, does everything possible to get rid of it... only to discover it's the gift of happiness.

From the same summary as above: how to deal with a value theme

- choose a value – for example Justice

- then find it a contrary value – for example Injustice

- then a contradictory value – for example Illegality

- then a negation of the negation – for example Tyranny

Scenes can be linked by what they have in common or what they have in opposition.

William Goldman: "give the audience what it wants, but not the way it expects".

In Aristotle's words, an ending must be both "inevitable and unexpected." Inevitable in the sense that as the Inciting Incident occurs, everything and anything seems possibel, but at the Climax, as the audience looks back throug hthe telling, it should seem that the path the telling took was the only path.

"The life story of each and every character offers encyclopedic possibilities. The mark of a master is to select only a few moments but give us a lifetime."

The ontollogy of story:

- Story values are universally salient parts of human experience which can change from positive to negative over time

- Story events are changes in value achieved through conflict

- A scene is an action through conflict in more or less contiguous space and time. Ideally a scene is also a story event.

- "A beat is an exchange of behaviour in action/reaction."

- "A sequence is a series of scenes - generally two to five - that culminates in a greater impact than any previous scene."

- "An act is a series of sequences that peaks in a climactic scene which causes a major reversal of values, more powerful in its impact than any previous sequence or scene".

- "A story is a series of acts that build to a last act climax or story climax which brings about absolute and irreversible changes."

Story dichotomies:

- Open vs closed ending: are we left with any unanswered questions or unfulfilled emotions?

- Internal vs external conflict

- Single vs multiple protagonists

- Active vs passive protagonist(s)

- Linear vs nonlinear time

- A causality vs coincidence led chain of events

- Consistent vs inconsistent realities (inconsistent realities jump between modes)

McKee even has a story triangle:

"The first step towards a well-told story is to create a small, knowable world. Artists by nature crave freedom, so the principle that the structure/setting relationship restricts creative hoices may stir the rebel in you."

If your finished screenplay contains every scene you've ever written, if you've never thrown an idea away, if your rewriting is little more than tinkering with dialogue, your work will almost certainly fail. No matter our talent, we all know in the midnight of our souls that 90 percent of what we do is less than our best. If, however, research inspires a pace of ten to one, even twenty to one, and if you then make brilliant choices to find that 10 percent of excellence and bum the rest, every scene will fascinate and the world will sit in awe of your genius.

No one has to see your failures unless you add vanity to folly and exhibit them. Genius consists not only of the power to create expressive beats and scenes, but of the taste, judgment, and will to weed out and destroy banalities, conceits, false notes, and lies.

Subgenres of horror:

- Uncanny: scary but rational

- Supernatural: scary and irrational

- Super-uncanny: you have to keep guessing whether it's rational or not

Some other interseting plots:

- Punitive plot: good guy goes bad and is punished

- Education plot: protagonist learns something about life

- Disillusionment plot: protagonist learns something bad about life

- Testing plot: the protagonist is tested

"To anticipate the anticipations of the audience you must master your genre and its conventions."

Hemingway, for example, was fascinated with the question of how to face death. After he witnessed the suicide of his father, it became the central theme, not only of his writing, but of his life. He chased death in war, in sport, on safari, until finally, putting a shotgun in his mouth, he found it. Charles Dickens, whose father was imprisoned for debt, wrote of the lonely child searching for the lost father over and over in David Coppeljield, Oliver Twist, and Great Expectations. Moliere turned a critical eye on the idiocy and depravity of seventeenth-century France and made a career writing plays whose titles read like a checklist of human vices: The Miser, The Misanthrope, The Hypochondriac. Each of these authors found his subject

and it sustained him over the long journey of the writer.

Screenwriting is not for sprinters, but for long-distance runners. Whatever your source of inspiration, beware of this: Long before you finish, the love of self will rot and die, the love of ideas sicken and perish. You'll become so tired and bored with writing about yourself or your ideas, you may not finish the race.

Characterization is the surface-observable aspects of the character. Deep Character is the stuff that's only revealed in dilemmas and crises.

Good writing not only reveals true character, but also changes the true character over the character arc.

The story should be designed to reveal and change the true character of the protagonist.

"In life, moments that blaze with a fusion of idea and emotion are so rare, when they happen you think you're having a religious experience."

For an artist must have not only ideas to express, but ideas to prove. Expressing an idea, in the sense of exposing it, is never enough. The audience must not just understand; it must believe. You want the world to leave your story convinced that yours is a truthful metaphor for life.

STORYTELLING is the creative demonstration of truth. A story is the living proof of an idea. the conversion of idea to action. A story's event structure is the means by which you first express. then prove your idea ... without explanation.

"A CONTROLLING IDEA may be expressed in a single sentence describing how and why life undergoes change from one condition of existence at the beginning to another at the end."

No matter your inspiration, ultimately the story embeds its Controlling Idea within the final climax, and when this event speaks its meaning, you will experience one of the most powerful moments in the writing life-Self-Recognition: The Story Climax mirrors your inner self, and if your story is from the very best sources within you, more often than not you'll be shocked by what you see reflected in it.

You may think you're a warm, loving human being until you find yourself writing tales of dark, cynical consequence. Or you may think you're a street-wise guy who's been around the block a few times until you find yourself writing warm, compassionate endings. You think you know who you are, but often you're amazed by what's skulking inside in need of expression. In other words, if a plot works out exactly as you first planned, you're not working loosely enough to give room to your imagination and instincts. Your story should surprise you again and again. Beautiful story design is a combination of the subject found,_ the imagination at work, and the mind loosely but wisely executing the craft.

A great work is a living metaphor that says, "Life is like this." The classics, down through the ages, give us not solutions but lucidity, not answers but poetic candor; they make inescapably clear the problems all generations must solve to be human.

Allegedly, a story should progress through not just the positive value at stake and its negation, but also a contrary value and a negation of the negation:

Convert exposition into ammunition. Your characters know their world, their history, each other, and themselves. Let the muse what they know as ammunition in their struggle to get what they want.

An interesting kind of rule:

Ask yourself, "If I were to strip the voice-over out of my screenplay, would the story still be well told?" If the answer is yes... keep it in.

Some types of relationship with audience:

- Mystery: the characters know more than the audience

- Closed mystery: murder happens off-stage and the question is: whodunnit?

- Open mystery: audience sees the murder and the question is: will they get away with it?

- Suspense: the characters and the audience know the same amount

- Dramatic irony: the audience knows more than the characters

Story creates meaning. Coincidence, then, would seem our enemy, for it is the random, absurd collisions of things in the universe and is, by definition, meaningless. And yet coincidence is a part of life… The solution, therefore, is not to avoid coincidence, but to dramatize how it may enter life meaninglessly, but in time gain meaning, how the antilogic of randomness becomes the logic of life-as-lived. First, bring coincicdence in early to allow time to build meaning out of it.

If you use coincidence to fix the character's problems, then that's Deus Ex Machina which is bad. So the characters should overcome coincidences, not be rescued by them.

The strengths of each medium:

- Written prose does internal conflict best by zooming into someone's thoughts

- Theatre does personal conflict best by conveying the live nuances of voice and having license to speak unrealistically

- Cinema does extra-personal conflict best by showing big scenes and big props

The more "pure" a novel or play - the more it is dominated by internal or personal conflict - the harder it will be to adapt to cinema

Cowardly writers try to kick sand over holes and hope the audience doesn't notice. Other writers face this problem anfully. They expose the hole to the audience, then deny that it is a hole.

"Everything I learned about human nature I learned from me" - Anton Checkov

Screen dialogue is essentially stikomythia, or a succession of short speeches. After each speech, get a reaction from the interlocutor, creating a series of action-reactions. This can also mean the character reacting to themself.

"Suspense sentences": the meaning of the sentence isn't revealed until the last word. Eg "If you didn't want me to do it, why'd you give me that..." (look? gun? kiss?)

External imagery has symbolic meaning outside the film, internal imagery only has meaning inside the film.

The dimensionality of a character is the amount of contradiction in the character.

The audience is drawn to identifying with the "Center of Good"

"Economy is key and brevity takes time"

Strong characters have both conscious and unconscious desires.

"Obligatory scene": a scene which the audience intuitively knows must eventually happen to bring everything together, such as a showdown between the hero and the villian.

"Major dramatic question": what's the central problem which needs solving?

More weird diagrams:

The second one shows the inciting incident as a shift from the status quo equilibrium.

Portrait of an artist:

He wants to destroy his work. Taste and experience tell him that 90 percent of everything he writes, regardless of his genius, is mediocre at best. In his patient search for quality, he must create far more material than he can use, then destroy it. He may sketch a scene a dozen different ways before finally throwing the idea of the scene out of the outline. He may destroy sequences, whole acts. A writer secure in his talent knows there’s no limit to what he can create, and so he trashes everything less than his best on a quest for a gem-quality story.

femto's review against another edition

4.0

Lo bueno de estos libros es la forma en que se siente que les hablan al lector, no es solo un conjunto de datos y ordenes, te enseña cosas sobre lo que significa escribir y lo que puede usarse para entender sobre la naturaleza humana, ya que como dice el libro, "toda historia es una metáfora de la realidad"

lisaebetz's review against another edition

5.0

Too much to absorb in one reading. Will have to spend more time with it, but hopefully what I've already understood will help as I plot out my next story.

I can see why this is a much-praised classic.

I can see why this is a much-praised classic.

wmhenrymorris's review against another edition

Totally lived up to the hype. A must read for anyone engaged in the art of storytelling in any capacity. Yes, it's geared towards producing screenplays, but 90% or more of it is fully applicable to other forms of fiction -- and even nonfiction.

Be warned that it spoils a bunch of movies, but all older movies so if you haven't seen Chinatown or Big or Terminator by now, you may want to clear those movies (and a few others) out of your Netflix queue. Or just forget about it, and read the book anyway.

One final thing I want to note: McKee both celebrates and takes it to the sloppy/poor work of both art films and standard "Hollywood" fare. No matter what genre you write or what pretensions you have, you need to read what he says about structure and substance. What's more, he quotes Henry James and Wayne Booth and Aristotle.

McKee has his critics, and (especially for novelists), he can only teach you so much, but his diagnosis of what's wrong with so many attempts at storytelling is right on and his remedies have already provoked some fruitful thinking for me in relation to my own in-progress stories. Sure, it's no substitute for a lot of hard work (and that's one of his points, actually), but, in general, those who dismiss the importance of structure and especially of tightening scenes, tend to produce work that shows the exact flabbiness and sloppiness that McKee is trying to get writers to avoid.

Be warned that it spoils a bunch of movies, but all older movies so if you haven't seen Chinatown or Big or Terminator by now, you may want to clear those movies (and a few others) out of your Netflix queue. Or just forget about it, and read the book anyway.

One final thing I want to note: McKee both celebrates and takes it to the sloppy/poor work of both art films and standard "Hollywood" fare. No matter what genre you write or what pretensions you have, you need to read what he says about structure and substance. What's more, he quotes Henry James and Wayne Booth and Aristotle.

McKee has his critics, and (especially for novelists), he can only teach you so much, but his diagnosis of what's wrong with so many attempts at storytelling is right on and his remedies have already provoked some fruitful thinking for me in relation to my own in-progress stories. Sure, it's no substitute for a lot of hard work (and that's one of his points, actually), but, in general, those who dismiss the importance of structure and especially of tightening scenes, tend to produce work that shows the exact flabbiness and sloppiness that McKee is trying to get writers to avoid.

bookaholiz's review against another edition

5.0

“In short, a story well told gives you the very thing you cannot get from life: meaningful emotional experience. In life, experiences become meaningful with reflection in time. In art, they are meaningful now, at the instant they happen.”

“The gift of story is the opportunity to live lives beyond our own, to desire and struggle in a myriad of worlds and times, at all the various of our being.”

--

This can be considered a textbook on screenwriting and in film studies as the author take you through all the basics while dissecting the anatomy of famous movies for examples. But more than that, it’s a criticism and a celebration of art, written beautifully. I’ve highlighted something almost every page. The author put words to all the time I felt something was not right or something was so good in a story yet couldn’t figure out why. Examples: Why didn't an adaptation work? Why did the movie's "life lesson" that should be meaningful turn pretentious? What makes a resolution to conflict unsatisfactory? And so on. Even though it’s a book on screenwriting, I think every writer of any medium could get something out of it.

More than art, stories are imitation of life, and authentic stories required their writers to bare their heart out on the paper. While celebrating the art of storytelling, Story felt like a celebration of the art of living as well. As we could not understand our own emotions and subconscious, we turn to art for therapy, whether as a creator or a spectator. Good art always deliver a momentarily release from the burden of life's unanswered riddles, and if they're really good, they might even provide a solution. Reading Story was therapeutic to me in that way because it helped bridge the gap between understanding of art and understanding of life.

However, as a textbook, it contains principles that may be rigid when applied to something as fluid as the art of storytelling. There are points the author made that might be debatable, as art is subjective and there are rules breakers that have proven that these principles are mere guidelines. Also, he might be standing from the point of view of a critic more than a writer, and a critic can be a miserable audience. There’s no doubt that spectacles and “cheap thrills” still work, and cliché is not always a bad thing. Not every movie go-er wants to come out feeling that their life have changed, sometimes it's just a pure need for entertainment. But that’s a thing with generations too, I supposed.

Nevertheless, it’s true that to make a movie memorable, it’s generally a story that matters. There are forgivable mistakes, but a clunky, poorly-handled script would surely be a turn-off, and no spectacles could save them, whether it be beautiful talented casts or tons of special effects. And as all the best rule breakers must’ve understood, you have to know the rules before breaking them.

Would recommend to all film lovers and aspiring writers everywhere.

tiggum's review against another edition

1.0

Holy shit, where to even start with this? It's bad in so many ways. The author comes across as a pompous, arrogant, narcissist who knows practically nothing and is even worse at communicating it. How is this guy so highly regarded? I feel dumber for having read this.

The actual content of this book, what little of it there is, is the most basic advice on writing mixed with the author's opinions on what makes a good movie (by which he clearly means what he personally likes, not what will make a popular or successful film), illustrations that actually make the text harder to understand, arbitrary classifications invented by the author, bizarre analogies, and endless examples of half-remembered films. How do you call yourself an expert on script writing and think the famous line is from Star Wars is "Go with the Force, go with the Force"?

McKee doesn't understand what words mean, he doesn't know what irony is, he doesn't understand metaphors, and he doesn't fact check anything. I mean, how difficult would it have been to get hold of a copy of Star Wars and see if you got the line right? Or maybe ask someone who speaks Chinese if it's true that the word for "crisis" is a combination of "danger" and "opportunity"? (It isn't)

All you'll learn from this book is which movies McKee likes, and I'll save you the time; it's Kramer vs. Kramer, Chinatown and Casablanca. There are pages and pages of transcripts and (bad, surface-level) analysis of films, and you'd think an expert on the medium could manage to find fresh examples each time, but in fact those three movies come up so often you'll feel like you've seen them just by reading this.

Oh, and he hates modern film and the modern world in general. Or rather, his warped idea of what the modern world is. "The art of story is in decay" he says; "contemporary "auteurs" cannot tell story with the power of the previous generation"; "more and more ours has become an age of moral and ethical cynicism, relativism, and subjectivism"; "the family disintegrates and sexual antagonisms rise". Children these days "[tyrannise their] parents", and whereas in the good old days families "[dressed] for dinner at a certain hour", now they "[feed] from an open refrigerator".

But it's not just film and the modern world he doesn't understand, it's everything: emotions; sex; cars; comics; families; music. If he talks about something you can guarantee he's going to say something bizarre about it. It's like he's an alien or a robot trying (very badly) to blend in with humanity. And at this point I've just got to quote some of the weird stuff he wrote.

'Love relationships are political. An old Gypsy expression goes: "He who confesses first loses." The first person to say "I love you" has lost because the other, upon hearing it, immediately smiles a knowing smile, realizing that he's the one loved, so he now controls the relationship.' - p 182.

The understanding of how we create the audience's emotional experience begins with the realization that there are only two emotions-pleasure and pain. - p 243.

You escape into your car, snap on the radio, and get in the proper lane according to the music. If classical, you hug the right; if pop, down the middle of the road; if rock, head left. - p 290.

It's just like sex. Masters of the bedroom arts pace their love-making. They begin by taking each other to a state of delicious tension short of-and we use the same word in both cases-climax, then tell a joke and shift positions before building each other to an even higher tension short of climax; then have a sandwich, watch TV, and gather energy to then reach greater and greater intensity, making love in cycles of rising tension until they finally climax simultaneously and the earth moves and they see colors. - p 291.

They saturate the screen with lush photography and lavish production values, then tie images together with a voice droning on the soundtrack, turning the cinema into what was once known as Classic Comic Books. Many of us were first exposed to the works of major writers by reading Classic Comics, novels in cartoon images with captions that told the story. That's fine for children, but it's not cinema. - p 344.

Murder Mysteries are like board games, cool entertainments for the mind. -p 351.

Jesus Christ, can you imagine paying to hear this guy's opinions on anything? I'm really glad I managed to find a free copy of this book, because I'd feel robbed if I'd paid as much as 5 cents for it.

The actual content of this book, what little of it there is, is the most basic advice on writing mixed with the author's opinions on what makes a good movie (by which he clearly means what he personally likes, not what will make a popular or successful film), illustrations that actually make the text harder to understand, arbitrary classifications invented by the author, bizarre analogies, and endless examples of half-remembered films. How do you call yourself an expert on script writing and think the famous line is from Star Wars is "Go with the Force, go with the Force"?

McKee doesn't understand what words mean, he doesn't know what irony is, he doesn't understand metaphors, and he doesn't fact check anything. I mean, how difficult would it have been to get hold of a copy of Star Wars and see if you got the line right? Or maybe ask someone who speaks Chinese if it's true that the word for "crisis" is a combination of "danger" and "opportunity"? (It isn't)

All you'll learn from this book is which movies McKee likes, and I'll save you the time; it's Kramer vs. Kramer, Chinatown and Casablanca. There are pages and pages of transcripts and (bad, surface-level) analysis of films, and you'd think an expert on the medium could manage to find fresh examples each time, but in fact those three movies come up so often you'll feel like you've seen them just by reading this.

Oh, and he hates modern film and the modern world in general. Or rather, his warped idea of what the modern world is. "The art of story is in decay" he says; "contemporary "auteurs" cannot tell story with the power of the previous generation"; "more and more ours has become an age of moral and ethical cynicism, relativism, and subjectivism"; "the family disintegrates and sexual antagonisms rise". Children these days "[tyrannise their] parents", and whereas in the good old days families "[dressed] for dinner at a certain hour", now they "[feed] from an open refrigerator".

But it's not just film and the modern world he doesn't understand, it's everything: emotions; sex; cars; comics; families; music. If he talks about something you can guarantee he's going to say something bizarre about it. It's like he's an alien or a robot trying (very badly) to blend in with humanity. And at this point I've just got to quote some of the weird stuff he wrote.

'Love relationships are political. An old Gypsy expression goes: "He who confesses first loses." The first person to say "I love you" has lost because the other, upon hearing it, immediately smiles a knowing smile, realizing that he's the one loved, so he now controls the relationship.' - p 182.

The understanding of how we create the audience's emotional experience begins with the realization that there are only two emotions-pleasure and pain. - p 243.

You escape into your car, snap on the radio, and get in the proper lane according to the music. If classical, you hug the right; if pop, down the middle of the road; if rock, head left. - p 290.

It's just like sex. Masters of the bedroom arts pace their love-making. They begin by taking each other to a state of delicious tension short of-and we use the same word in both cases-climax, then tell a joke and shift positions before building each other to an even higher tension short of climax; then have a sandwich, watch TV, and gather energy to then reach greater and greater intensity, making love in cycles of rising tension until they finally climax simultaneously and the earth moves and they see colors. - p 291.

They saturate the screen with lush photography and lavish production values, then tie images together with a voice droning on the soundtrack, turning the cinema into what was once known as Classic Comic Books. Many of us were first exposed to the works of major writers by reading Classic Comics, novels in cartoon images with captions that told the story. That's fine for children, but it's not cinema. - p 344.

Murder Mysteries are like board games, cool entertainments for the mind. -p 351.

Jesus Christ, can you imagine paying to hear this guy's opinions on anything? I'm really glad I managed to find a free copy of this book, because I'd feel robbed if I'd paid as much as 5 cents for it.