Take a photo of a barcode or cover

emotional

inspiring

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

emotional

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

The giving tree father daughter edition. It also had a bit of "The Grand Inquisitor" thrown in for good measure.

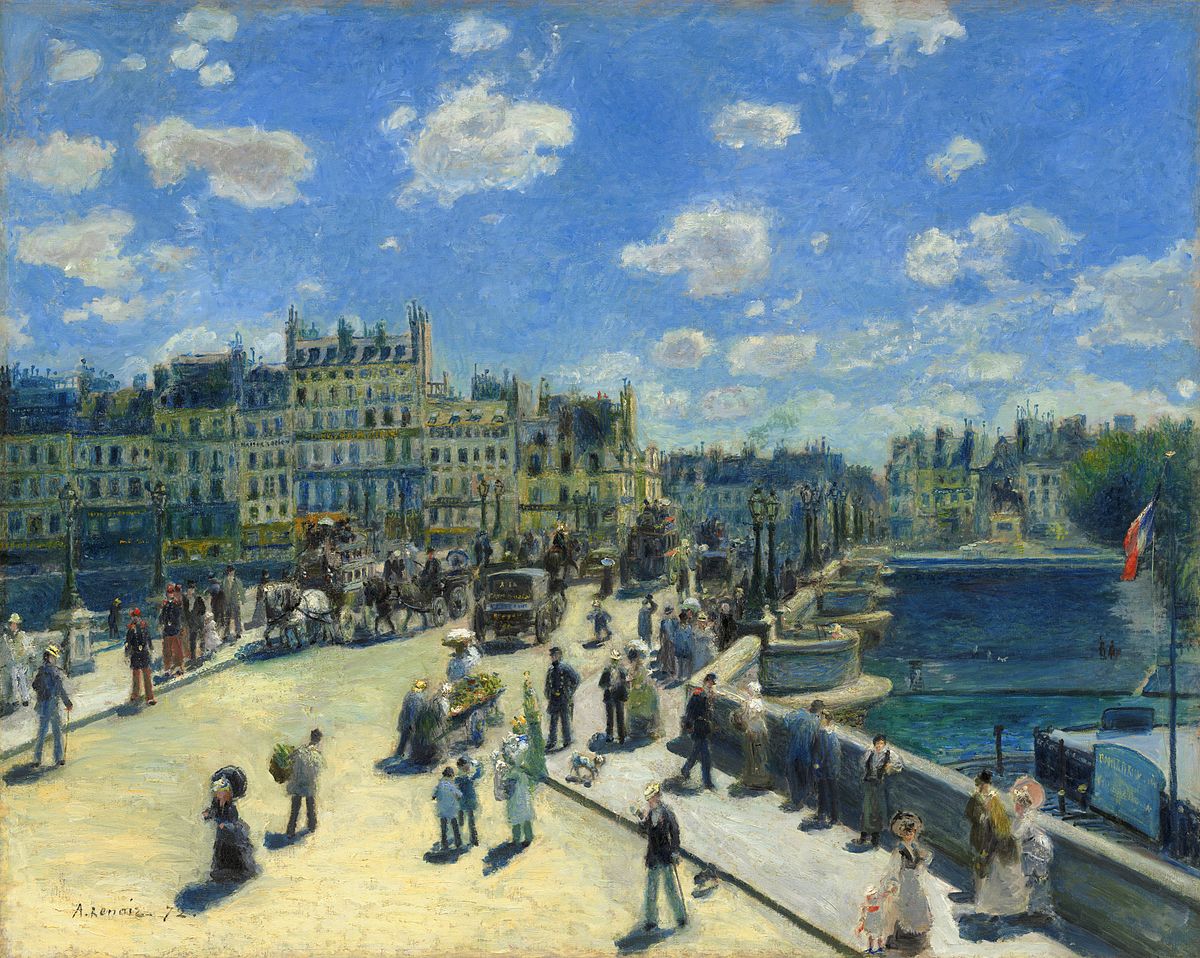

60th book of 2021. Artist for this review is French painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

My first Balzac, and I am left impressed. Starting it, I wondered if this would be those fairly short novels that feel 100 pages longer, but that fear quickly disappeared. It does begin with a lengthy (in true 19thC fashion) description of a boarding-house and its inhabitants, which makes for slow progress, especially attempting to commit the French names to memory, but as soon as the story begins, the narrative becomes readable and enjoyable. Balzac (or rather, Krailsheimer) surprised me with its readability. Set in 1819, just three years after the Battle of Waterloo, the backdrop to Balzac's novel is a Paris in love with money, affluence and social status.

"Pont Neuf"—1872

The titular Père Goriot doesn't hold down the narrative in the beginning, instead we follow Eugène de Rastignac, a law student. Rastignac is in the boarding-house with Goriot though, and the mysterious ex-convict Vautrin. Père Goriot is book 23 of his 89 (give or take, depending) book/story multi-volume collection, La Comédie humaine. Balzac divided the novels into subcatergories, so to speak, within the collection. He first placed Père Goriot into "Scènes de la vie parisienne" [Scenes of Life in Paris, one translation says], but later moved it, perhaps more aptly I would agree into, "Scènes de la vie privée" [Scenes of private life]. Above all, this is a personal novel about Goriot and his daughters, in true Lear fashion.

Goriot is an old man, the butt of many jokes, mocked and ridiculed, and misunderstood. He appears to be obsessed with two young and beautiful women who walk in the high social classes of Parisian life, but of course, they are his daughters. Where they are rich, finely-dressed, respected members of society, Goriot lives in the dilapidated boarding-house with no curtains over his windows. His obsessive love for them has led him to financial and personal ruin. In a Paris that is drawn by Balzac as caring only for money, status, Goriot stands alone. Rastignac attempts to enter the social-circles of Paris to win one of Goriot's daughters and all the while the mysterious Vautrin lurks on the fringe.

Vautrin's character was one of the highlights of the novel and his long monologue to Rastignac in the second part, "Entry on the Social Scene" was the best part of the novel. Being a French realist work, similar to that of Les Misérables (I'll come back to this point in a moment), I actually found Balzac's work better, at times. Vaurtin's speech is brilliant. I wish I could transcribe the lot.

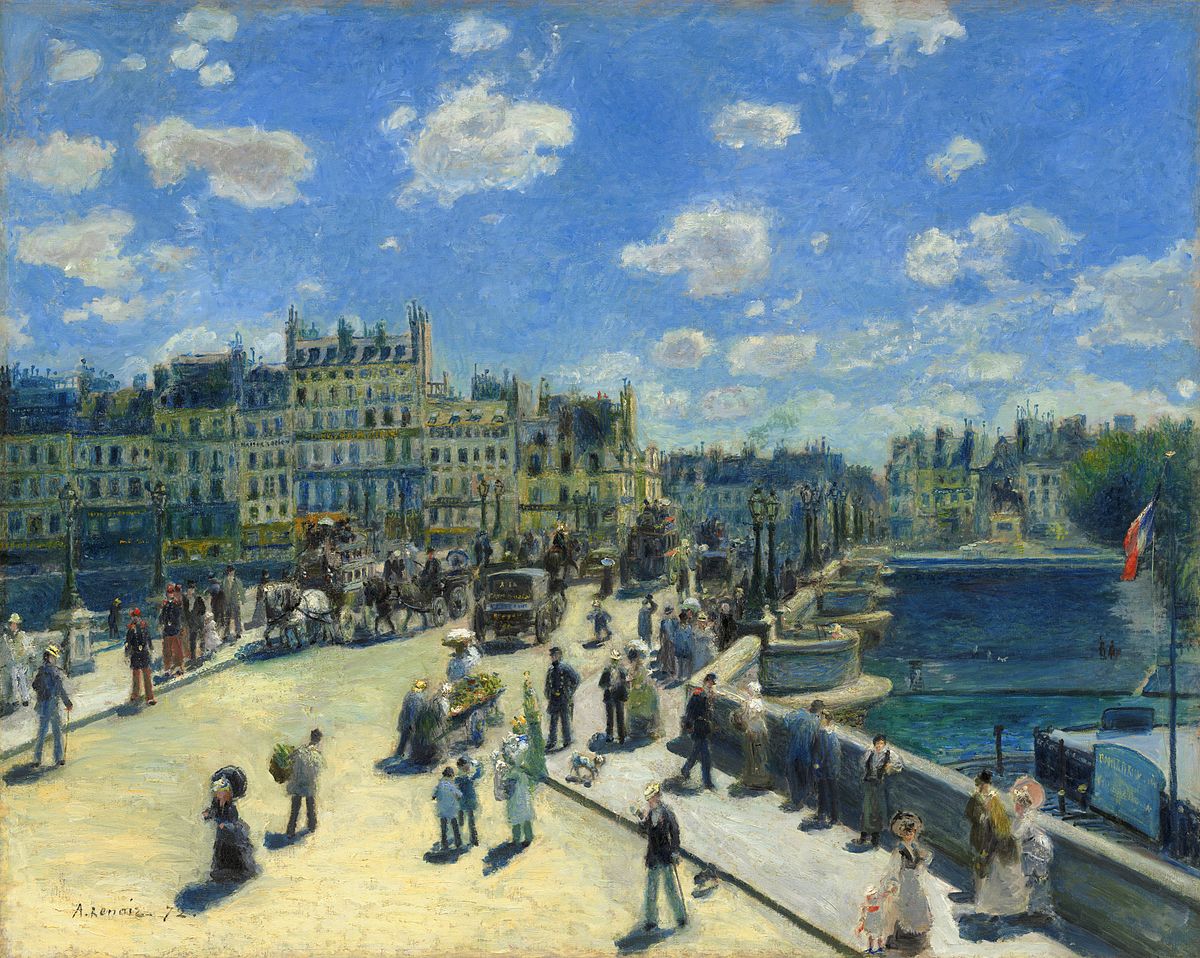

"Le Pont des Arts"—1867

Eventually the novel comes around to Goriot, and we see his misfortune played out, or, his sacrifice. His selflessness almost appears ridiculous. The final chapter is quite slow, after the climax of Vautrin's role in the narrative. Which is where, I would like to mention something else. I want to avoid using the dreaded spoiler-tag, but I do think there are huge similarities between this novel and Hugo's Les Misérables. I'll keep it fairly vague but Goriot reminded me slightly of Jean Valjean when he is the subject of great intrigue for a town, walking around, the mysterious old man, with seemingly a lot of money. And Vautrin is an ex-convict, just like Jean Valjean, and there is a scene in the middle of Père Goriot that is so similar to a scene in Les Misérables that I was getting my wires crossed. Père Goriot was published thirty years prior and Jean Valjean seemed to me like a combination of both Goriot's and Vautrin's character.

I will read more Balzac in the coming years. If I could have a whole novel of Vautrin's speeches then I would probably read it. Brilliant. I cared less about the sentimentality of Goriot, but that's because I'm an unromantic cynic myself. It can't be helped.

He saw society as an ocean of mire into which one had only to dip a toe to be buried in it up to the neck.

My first Balzac, and I am left impressed. Starting it, I wondered if this would be those fairly short novels that feel 100 pages longer, but that fear quickly disappeared. It does begin with a lengthy (in true 19thC fashion) description of a boarding-house and its inhabitants, which makes for slow progress, especially attempting to commit the French names to memory, but as soon as the story begins, the narrative becomes readable and enjoyable. Balzac (or rather, Krailsheimer) surprised me with its readability. Set in 1819, just three years after the Battle of Waterloo, the backdrop to Balzac's novel is a Paris in love with money, affluence and social status.

"Pont Neuf"—1872

The titular Père Goriot doesn't hold down the narrative in the beginning, instead we follow Eugène de Rastignac, a law student. Rastignac is in the boarding-house with Goriot though, and the mysterious ex-convict Vautrin. Père Goriot is book 23 of his 89 (give or take, depending) book/story multi-volume collection, La Comédie humaine. Balzac divided the novels into subcatergories, so to speak, within the collection. He first placed Père Goriot into "Scènes de la vie parisienne" [Scenes of Life in Paris, one translation says], but later moved it, perhaps more aptly I would agree into, "Scènes de la vie privée" [Scenes of private life]. Above all, this is a personal novel about Goriot and his daughters, in true Lear fashion.

Goriot is an old man, the butt of many jokes, mocked and ridiculed, and misunderstood. He appears to be obsessed with two young and beautiful women who walk in the high social classes of Parisian life, but of course, they are his daughters. Where they are rich, finely-dressed, respected members of society, Goriot lives in the dilapidated boarding-house with no curtains over his windows. His obsessive love for them has led him to financial and personal ruin. In a Paris that is drawn by Balzac as caring only for money, status, Goriot stands alone. Rastignac attempts to enter the social-circles of Paris to win one of Goriot's daughters and all the while the mysterious Vautrin lurks on the fringe.

Vautrin's character was one of the highlights of the novel and his long monologue to Rastignac in the second part, "Entry on the Social Scene" was the best part of the novel. Being a French realist work, similar to that of Les Misérables (I'll come back to this point in a moment), I actually found Balzac's work better, at times. Vaurtin's speech is brilliant. I wish I could transcribe the lot.

'Fifty thousand young men in the same position as you are all trying to solve the problem of how to get rich quick. You are just one of all that number. Imagine the efforts that will demand and how bitter the struggle will be. You'll have to devour each other like crabs in a pot, since there aren't fifty thousand jobs going. Do you know the way to get on here? Through brilliant intelligence or skilful corruption. Either plough into the mass of mankind like a cannonball, or infiltrate them like a plague. It's no good being honest. Men yield to the power of intelligence, though they hate it and try to decry it, because it takes but does not share. But they yield if it is persistent. In a word they kneel before it in worship once they have failed to bury it in mud. Corruption thrives, talent is rare, so corruption is the weapon of mediocre majority, and you will feel it pricking you wherever you go. You will see women whose husbands earn sixty thousand francs all told spending more than ten thousand on clothes. You will see clerks on twelve hundred a year buying land. You will see women selling themselves so that they can ride in a carriage with the son of a peer of the realm and go bowling off to Longchamp down the middle of the road. You have seen that poor old ninny Père Goriot obliged to pay off the bill of exchange endorsed by his daughter, whose husband has an income of fifty thousand a year. I defy you to go two steps in Paris without running across some diabolical fiddle.'

"Le Pont des Arts"—1867

Eventually the novel comes around to Goriot, and we see his misfortune played out, or, his sacrifice. His selflessness almost appears ridiculous. The final chapter is quite slow, after the climax of Vautrin's role in the narrative. Which is where, I would like to mention something else. I want to avoid using the dreaded spoiler-tag, but I do think there are huge similarities between this novel and Hugo's Les Misérables. I'll keep it fairly vague but Goriot reminded me slightly of Jean Valjean when he is the subject of great intrigue for a town, walking around, the mysterious old man, with seemingly a lot of money. And Vautrin is an ex-convict, just like Jean Valjean, and there is a scene in the middle of Père Goriot that is so similar to a scene in Les Misérables that I was getting my wires crossed. Père Goriot was published thirty years prior and Jean Valjean seemed to me like a combination of both Goriot's and Vautrin's character.

I will read more Balzac in the coming years. If I could have a whole novel of Vautrin's speeches then I would probably read it. Brilliant. I cared less about the sentimentality of Goriot, but that's because I'm an unromantic cynic myself. It can't be helped.

The Ugly Sisters…

Eugène de Rastignac has taken a room in Madame Vauquer’s boarding house in a run-down area of Paris. Among the many other lodgers, there is one old man, known to all as Père Goriot. When he had arrived several years earlier, he had apparently been relatively wealthy, and Mme Vauquer had seen him as a potential husband. But he has grown gradually poorer, and she has come to treat him with petty spite, in which she is joined by the other lodgers. Père Goriot is blissfully unconcerned by their contempt however. He has one obsession in life and it leaves no room for other concerns – his two daughters, Goneril and Regan . . . oops, I mean, Delphine and Anastasie. These two delightful young women have both managed to snaffle rich husbands, mainly because of the money their father lavished on getting them into a higher stratum of society than his own. And they have repaid him by disowning him as too low class to be invited to their glittering homes and social occasions. But they haven’t cut themselves off from him completely – they still pop by any time they need money to pay their gambling debts or the blackmail that comes as a side-effect of their streams of lovers. Hence Goriot’s increasing poverty, but his idolatry of his daughters remains undiminished.

Eugène is a law student, but he doesn’t see the practice of law as the quickest or surest way of getting rich, which is his sole aspiration in life. Rather, he’s looking for a way to inveigle himself into high society by finding himself a wealthy patroness. So when he discovers that Goriot has two wealthy, bored, discontented daughters, he sees an opening for himself. But Vautrin, another of the lodgers and the villain of the piece (though frankly not much worse than all the rest of them), has another plan to make Eugène rich, for a cut, of course – a plan that involves crime. And while Eugène is a little horrified at first, he doesn’t totally dismiss the idea…

There is so much cynicism in this book that there’s really very little room for anything else. There are a couple of semi-decent human beings among the lodgers, but they are consigned to minor roles. Goriot would be sympathetic if only he weren’t quite so fawningly obsessed by his revolting daughters, whom I soon began to refer to as the Ugly Sisters – a reference to their souls rather than their faces. The way he talks about their beauty is more like the ravings of a young man in love than a father, and made me feel quite creeped out at points. And his encouragement of them to involve themselves in adulterous relationships is odd, to say the least. Still, at least he is more concerned about their welfare than his own, which is a welcome relief from the unrelenting self-absorption of all the other main characters. Eugène occasionally shows signs that there is a better man inside him trying to get out, but one feels the attempt will be futile. Like the Ugly Sisters, Eugène is funded by a doting parent and has no compunction about driving her and his siblings deeper into poverty so that he can skip his lessons and attempt to become a gigolo.

You’ll have gathered that I found the characters ranged from unpleasant to obnoxious. I pretty soon realised that I was hoping for a tragic ending for them all. However, while I felt there weren’t enough decent people to provide a balance, I also felt that individually each of the characters was well-drawn and believable. Paris becomes a character in her own right, and Balzac seems to suggest that the corruption and greed of the characters is a reflection of this great city at a time of political and social upheaval – the book is set in 1819, four years after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. Balzac shows the vast differences in wealth and class, all happening in a small geographical zone. There are only a few streets separating the boarding house from the houses of the aristocracy, and it is a time when people’s fortunes have been made or destroyed on the basis of whether they backed the winning side in the social unrest. Even now, the characters can’t be sure how long the current stability will last, so there’s a feeling of eat, drink and be merry about the amorality of the rich, for tomorrow the winning side may be the losing side.

There are long parts filled with description, or with characters making lengthy and unrealistic speeches to each other explaining their moral stance on life, and I found these often became excruciatingly dull. But when Balzac actually remembers that he’s supposed to be telling a story rather than giving a social sciences lecture, he does it very well. The second half becomes quite action-packed (relatively speaking), as all these amoral people plot to gain advantage at the expense of each other. It’s quite fun at points, with some elements of farce, but overall it is a bleak and depressing view of humanity. There is indeed tragedy at the end, though not for everyone, and while I’d spent the early part of the book wishing plagues and pestilence upon them all, in fact I ended up quite moved by… nope, can’t tell you – spoiler! I wouldn’t say Balzac shows signs of becoming a favourite author on the basis of this one, but I enjoyed it enough to want to read more.

www.fictionfanblog.wordpress.com

Eugène de Rastignac has taken a room in Madame Vauquer’s boarding house in a run-down area of Paris. Among the many other lodgers, there is one old man, known to all as Père Goriot. When he had arrived several years earlier, he had apparently been relatively wealthy, and Mme Vauquer had seen him as a potential husband. But he has grown gradually poorer, and she has come to treat him with petty spite, in which she is joined by the other lodgers. Père Goriot is blissfully unconcerned by their contempt however. He has one obsession in life and it leaves no room for other concerns – his two daughters, Goneril and Regan . . . oops, I mean, Delphine and Anastasie. These two delightful young women have both managed to snaffle rich husbands, mainly because of the money their father lavished on getting them into a higher stratum of society than his own. And they have repaid him by disowning him as too low class to be invited to their glittering homes and social occasions. But they haven’t cut themselves off from him completely – they still pop by any time they need money to pay their gambling debts or the blackmail that comes as a side-effect of their streams of lovers. Hence Goriot’s increasing poverty, but his idolatry of his daughters remains undiminished.

Eugène is a law student, but he doesn’t see the practice of law as the quickest or surest way of getting rich, which is his sole aspiration in life. Rather, he’s looking for a way to inveigle himself into high society by finding himself a wealthy patroness. So when he discovers that Goriot has two wealthy, bored, discontented daughters, he sees an opening for himself. But Vautrin, another of the lodgers and the villain of the piece (though frankly not much worse than all the rest of them), has another plan to make Eugène rich, for a cut, of course – a plan that involves crime. And while Eugène is a little horrified at first, he doesn’t totally dismiss the idea…

There is so much cynicism in this book that there’s really very little room for anything else. There are a couple of semi-decent human beings among the lodgers, but they are consigned to minor roles. Goriot would be sympathetic if only he weren’t quite so fawningly obsessed by his revolting daughters, whom I soon began to refer to as the Ugly Sisters – a reference to their souls rather than their faces. The way he talks about their beauty is more like the ravings of a young man in love than a father, and made me feel quite creeped out at points. And his encouragement of them to involve themselves in adulterous relationships is odd, to say the least. Still, at least he is more concerned about their welfare than his own, which is a welcome relief from the unrelenting self-absorption of all the other main characters. Eugène occasionally shows signs that there is a better man inside him trying to get out, but one feels the attempt will be futile. Like the Ugly Sisters, Eugène is funded by a doting parent and has no compunction about driving her and his siblings deeper into poverty so that he can skip his lessons and attempt to become a gigolo.

You’ll have gathered that I found the characters ranged from unpleasant to obnoxious. I pretty soon realised that I was hoping for a tragic ending for them all. However, while I felt there weren’t enough decent people to provide a balance, I also felt that individually each of the characters was well-drawn and believable. Paris becomes a character in her own right, and Balzac seems to suggest that the corruption and greed of the characters is a reflection of this great city at a time of political and social upheaval – the book is set in 1819, four years after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. Balzac shows the vast differences in wealth and class, all happening in a small geographical zone. There are only a few streets separating the boarding house from the houses of the aristocracy, and it is a time when people’s fortunes have been made or destroyed on the basis of whether they backed the winning side in the social unrest. Even now, the characters can’t be sure how long the current stability will last, so there’s a feeling of eat, drink and be merry about the amorality of the rich, for tomorrow the winning side may be the losing side.

There are long parts filled with description, or with characters making lengthy and unrealistic speeches to each other explaining their moral stance on life, and I found these often became excruciatingly dull. But when Balzac actually remembers that he’s supposed to be telling a story rather than giving a social sciences lecture, he does it very well. The second half becomes quite action-packed (relatively speaking), as all these amoral people plot to gain advantage at the expense of each other. It’s quite fun at points, with some elements of farce, but overall it is a bleak and depressing view of humanity. There is indeed tragedy at the end, though not for everyone, and while I’d spent the early part of the book wishing plagues and pestilence upon them all, in fact I ended up quite moved by… nope, can’t tell you – spoiler! I wouldn’t say Balzac shows signs of becoming a favourite author on the basis of this one, but I enjoyed it enough to want to read more.

www.fictionfanblog.wordpress.com

emotional

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Stackars gamle Goriot ;,(

emotional

inspiring

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Enjoyed this a lot. Old Goriot is masterfully put together, and even though the plot could drag at certain points, I found that to be easily ignored cause all the characters were so well developed, with a lot of depth that it just drives you to keep reading, which is something you don't often find in classical literature. This is also one of the most depressing books I've ever read. It made me mad and absolutely miserable but that's very much the point the point of the story.

(2.5* maybe?)

At around 100 pages, this book was really interesting and I enjoyed the dramatic aspect and side plots. But, for some reason, at the end it just got underwhelming and overall tiring.

The things I liked: Rastignac and his relationship with Goriot in the end, descriptions of the places and Balzac's ability to show us exactly what he wad thinking, also, the boarding house that he stayed in had interesting relationship and I liked interaction between the characters.

The things that weren't done well: Frirstly, Goriot in literally two pages changed his thoughts about his daughters. I know that he isn't dumb and that he knew that they were using him, but from naive character he became strangely conscious in the shortest amount of time. Vautrin's backstory is also not completly explained as well as the very end and main character's confusing sentance. The father-daughter relationship was over the top at some poins; strange, cringy and creepy.

Moreover, racism and slavery. I know that that were the common topics in that period of time, but I wasn't comfortable reading about it in a way that this book handeled them.

Overall, this book really had potential. At one point, it was a four star read for me, but I wasn't really a fan in the end. Sorry.

At around 100 pages, this book was really interesting and I enjoyed the dramatic aspect and side plots. But, for some reason, at the end it just got underwhelming and overall tiring.

The things I liked: Rastignac and his relationship with Goriot in the end, descriptions of the places and Balzac's ability to show us exactly what he wad thinking, also, the boarding house that he stayed in had interesting relationship and I liked interaction between the characters.

The things that weren't done well: Frirstly, Goriot in literally two pages changed his thoughts about his daughters. I know that he isn't dumb and that he knew that they were using him, but from naive character he became strangely conscious in the shortest amount of time. Vautrin's backstory is also not completly explained as well as the very end and main character's confusing sentance. The father-daughter relationship was over the top at some poins; strange, cringy and creepy.

Moreover, racism and slavery. I know that that were the common topics in that period of time, but I wasn't comfortable reading about it in a way that this book handeled them.

Overall, this book really had potential. At one point, it was a four star read for me, but I wasn't really a fan in the end. Sorry.