Scan barcode

fl44me's review against another edition

on attempted suicide and the state of mind before death; from brendon across a fence with rolling papers inside

hadenriles's review against another edition

4.0

Witty, racy, and maybe even a little exhilarating, it's an understandable predicament to be frustrated with a piece like this one. This is not Huxley at his prime, and for anyone who went from something like Brave New World to this, they might be sorely disappointed. In a way, Antic Hay feels like Huxley flexing his cerebral musculature and preparing to butcher.

In a dazzling array of linguistic and soaring cognoscente acrobatics, which, I suspect, and truthfully do not always understand myself, must be more than most of the reason people are frustrated with this book, given the relatively loose plot and flabby characters; Huxley, like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, gives us a lens that is damned near impossible to see through without the assistance of a fucking lexicon. The most difficult aspect of this book is having to stop every couple of pages to use Google. I mean it when I say 'soaring' intellectualism; Huxley was not one of the pre-eminent intellectuals of his time for nothing.

The loose plot-line that does exist doesn't seem to be much more than a joke and the ebbing, weaving jabs of uninvolved, intensely loquacious, and nigh-inhuman characters don't lend themselves to what feels like should be a good novel. It remains, regardless, a witty and poignant commentary on the decline of western civilization, particularly that of the British gentry, its social and economic whims, and a bunch of other stuff.

It is fantastic! despite whatever traditional limitations people want to dollop on top of it. You may have to dedicate yourself, though. Put forth a little more willpower, maybe even read it again, and, in the end, it will have been worth it.

Antic Hay is not incoherent; or, rather, I believe that any incoherence is purposeful because the story isn't the point; it's more of a tool, I think, for skewering big-headed socialites, gross elitism, and the mass wave of pleasant uselessness that has continually overtaken modern society. Disillusionment is a feeling, and the lives and detachment of every person in this novel, aside from Lypiatt, is an example of that deadly leisure and 'modern' carelessness. Don't judge this book by how you believe books should work; simply try to enjoy it. And don't forget the lexicon.

In a dazzling array of linguistic and soaring cognoscente acrobatics, which, I suspect, and truthfully do not always understand myself, must be more than most of the reason people are frustrated with this book, given the relatively loose plot and flabby characters; Huxley, like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, gives us a lens that is damned near impossible to see through without the assistance of a fucking lexicon. The most difficult aspect of this book is having to stop every couple of pages to use Google. I mean it when I say 'soaring' intellectualism; Huxley was not one of the pre-eminent intellectuals of his time for nothing.

The loose plot-line that does exist doesn't seem to be much more than a joke and the ebbing, weaving jabs of uninvolved, intensely loquacious, and nigh-inhuman characters don't lend themselves to what feels like should be a good novel. It remains, regardless, a witty and poignant commentary on the decline of western civilization, particularly that of the British gentry, its social and economic whims, and a bunch of other stuff.

It is fantastic! despite whatever traditional limitations people want to dollop on top of it. You may have to dedicate yourself, though. Put forth a little more willpower, maybe even read it again, and, in the end, it will have been worth it.

Antic Hay is not incoherent; or, rather, I believe that any incoherence is purposeful because the story isn't the point; it's more of a tool, I think, for skewering big-headed socialites, gross elitism, and the mass wave of pleasant uselessness that has continually overtaken modern society. Disillusionment is a feeling, and the lives and detachment of every person in this novel, aside from Lypiatt, is an example of that deadly leisure and 'modern' carelessness. Don't judge this book by how you believe books should work; simply try to enjoy it. And don't forget the lexicon.

buddhafish's review against another edition

4.0

171st book of 2020.

Huxley’s 20s satires are equally frustrating as they are quite brilliant. They are largely plotless; if you look hard enough, there is a semblance of a plot driving through, but by and large, the book meanders, to use Alison’s term from the novel-structure book I read recently Meander, Spiral, Explode. At the core of the novel, Huxley is shedding light on the lost generation that emerged after the First World War, as Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises did. It could be argued that like Hemingway’s 1926 novel, Antic Hay is also a roman à clef. I have read that Huxley is Gumbril in the novel, or at least based on himself, as the woman in the novel is based on a woman who snubbed him.

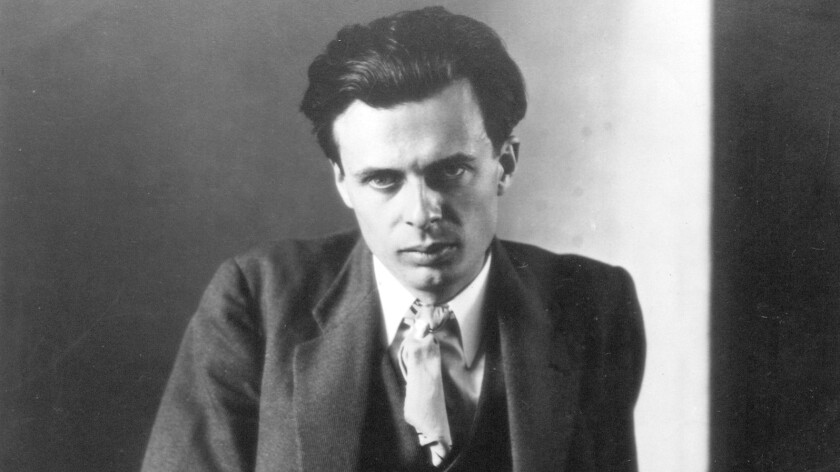

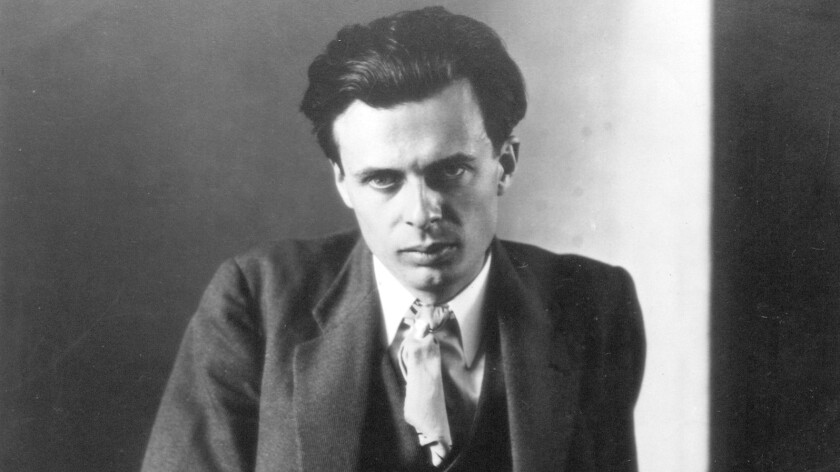

Huxley—Photo from the Los Angeles Times

Antic Hay is often described as a “novel of ideas”. In a 1958 interview, Huxley says this of 19th century literature:

“I was reading just the other day as I was travelling through Sicily, reading Trollope’s family parsonage and thinking how wonderful it was for novelists in those happy days to have a completely rigid framework, everybody knew exactly where they stood and it was possible to make your comments from an accepted ground.” The interviewer asks him if that has gone today. Huxley says, “It seems to have quite gone today.”

Huxley was writing at the height of modernism and Antic Hay was published just a year after Ulysses, perhaps the very pinnacle of modernism. As Huxley said in 1958, the novel was changing, the novel had changed. Antic Hay follows a cast of characters, all searching for meaning and happiness in their lives, and many failing, I suppose. Words like disillusionment and disenchantment are perfect for the novel’s tone and themes. As with his first novel, Crome Yellow, Huxley inserts a great number of intellectual and philosophical debates into his novel, which I think, today, would be frowned upon. These discussions do not advance the plot, they advance character to some degree, but on the whole they are a way of exploring the ideas Huxley was thinking about at the time (many of which were precursors to Brave New World): capitalism, money, art, drugs, sex, war, and so on. Its open discussion on such topics, predominantly because of its treatment of sex, Antic Hay was banned in Australia for a time and even burnt in Cairo—a surprising fate for a “comic” novel.

Despite its plotless body, the novel is an entertaining read. Gumbril, who could be seen as the “main” character, especially if it is indeed Huxley himself, is attempting to invent and make money from trousers that contain a pneumatic cushion in them, so the wearer could sit anywhere and be comfortable. He is also searching for love, and meaning, in the scattered world following the end of the War.

It is certainly a “novel of ideas”—I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who isn’t interested in reading long dialogues about art, philosophy and culture, or particularly interested in Huxley’s wit or ability to write. Antic Hay, if anything, proves again how talented he was at the latter. He once said that Balzac “almost ruined himself as a novelist by stuffing everything into his novels, everything he knew and everything he thought about” [this is the interviewer paraphrasing Huxley]. Huxley himself ran the same risk. He says himself all he wanted to write was a good novel, and never thought he had. He thought once or twice perhaps he’d pulled off the balance of combing “ideas” with “fiction”, but it was a balance that caused great difficulty. Antic Hay might not have pulled it off entirely, but it does not suffer from it; it is a good, enjoyable novel, and full of wisdom, even if it is too didactic at times. To end is an example of Huxley’s lovely, long “ideas”:

Huxley’s 20s satires are equally frustrating as they are quite brilliant. They are largely plotless; if you look hard enough, there is a semblance of a plot driving through, but by and large, the book meanders, to use Alison’s term from the novel-structure book I read recently Meander, Spiral, Explode. At the core of the novel, Huxley is shedding light on the lost generation that emerged after the First World War, as Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises did. It could be argued that like Hemingway’s 1926 novel, Antic Hay is also a roman à clef. I have read that Huxley is Gumbril in the novel, or at least based on himself, as the woman in the novel is based on a woman who snubbed him.

Huxley—Photo from the Los Angeles Times

Antic Hay is often described as a “novel of ideas”. In a 1958 interview, Huxley says this of 19th century literature:

“I was reading just the other day as I was travelling through Sicily, reading Trollope’s family parsonage and thinking how wonderful it was for novelists in those happy days to have a completely rigid framework, everybody knew exactly where they stood and it was possible to make your comments from an accepted ground.” The interviewer asks him if that has gone today. Huxley says, “It seems to have quite gone today.”

Huxley was writing at the height of modernism and Antic Hay was published just a year after Ulysses, perhaps the very pinnacle of modernism. As Huxley said in 1958, the novel was changing, the novel had changed. Antic Hay follows a cast of characters, all searching for meaning and happiness in their lives, and many failing, I suppose. Words like disillusionment and disenchantment are perfect for the novel’s tone and themes. As with his first novel, Crome Yellow, Huxley inserts a great number of intellectual and philosophical debates into his novel, which I think, today, would be frowned upon. These discussions do not advance the plot, they advance character to some degree, but on the whole they are a way of exploring the ideas Huxley was thinking about at the time (many of which were precursors to Brave New World): capitalism, money, art, drugs, sex, war, and so on. Its open discussion on such topics, predominantly because of its treatment of sex, Antic Hay was banned in Australia for a time and even burnt in Cairo—a surprising fate for a “comic” novel.

Despite its plotless body, the novel is an entertaining read. Gumbril, who could be seen as the “main” character, especially if it is indeed Huxley himself, is attempting to invent and make money from trousers that contain a pneumatic cushion in them, so the wearer could sit anywhere and be comfortable. He is also searching for love, and meaning, in the scattered world following the end of the War.

It is certainly a “novel of ideas”—I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who isn’t interested in reading long dialogues about art, philosophy and culture, or particularly interested in Huxley’s wit or ability to write. Antic Hay, if anything, proves again how talented he was at the latter. He once said that Balzac “almost ruined himself as a novelist by stuffing everything into his novels, everything he knew and everything he thought about” [this is the interviewer paraphrasing Huxley]. Huxley himself ran the same risk. He says himself all he wanted to write was a good novel, and never thought he had. He thought once or twice perhaps he’d pulled off the balance of combing “ideas” with “fiction”, but it was a balance that caused great difficulty. Antic Hay might not have pulled it off entirely, but it does not suffer from it; it is a good, enjoyable novel, and full of wisdom, even if it is too didactic at times. To end is an example of Huxley’s lovely, long “ideas”:

“There are quiet places also in the mind,” he said, meditatively. “But we build bandstand and factories on them. Deliberately—to put a stop to the quietness. We don’t like the quietness. All the thoughts, all the preoccupation in my head—round and round continually.” He made a circular motion with his hands. “And the jazz bands, the music hall songs, the boys shouting the news. What’s it all for? To put an end to the quiet, to break it up and disperse it, to pretend at any cost it isn’t there. Ah, but it is, it is there, in spite of everything, at the back of everything. Lying awake at night, sometimes—not restlessly, but serenely, waiting for sleep—the quiet re-establishes itself, piece by piece; all the broken bits, all the fragments of it we’ve been so busily dispersing all day long. It re-establishes itself, an inward quiet, like this outward quiet of grass and trees. It fills one, it grows –a crystal quiet, a growing expanding crystal. It grows, it becomes more perfect; it is beautiful and terrifying, yes, terrifying, as well as beautiful. For one’s alone in the crystal and there’s no support from outside, there’s nothing external and important, nothing external and trivial to pull oneself up by or to stand up, superiorly, contemptuously, so that one can look down. There’s nothing to laugh at or feel enthusiastic about. But the quiet grows and grows. Beautifully and unbearably. And at last you are conscious of something approaching; it is almost a faint sound of footsteps. Something inexpressibly lovely and wonderful advances through the crystal, nearer, nearer. And oh, inexpressibly terrifying. For if it were to touch you, if it were to seize and engulf you, you’d die; all the regular habitual, daily part of you would die. There would be and end of bandstands and whizzing factories, and one would have to begin living arduously in the quiet, arduously n some strange unheard-of manner. Nearer, nearer come the steps; but one can’t face the advancing thing. One daren’t. It’s too terrifying; it’s too painful to die. Quickly, before it is too late, start the factory wheels, bang the drum, blow up the saxophone. Think of the women you’d like to sleep with, the schemes for making money, the gossip about your friends, the last outrage of the politicians. Anything for a diversion. Break the silence, smash the crystal to pieces. There, it lies in bits; it is easily broken, hard to build up and easy to break. And the steps? Ah, those have taken themselves off, double quick. Double quick, they were gone at the flawing of the crystal. And by this time the lovely and terrifying thing is three infinities away, at least. And you lie tranquilly on your bed, thinking of what you’d do if you had ten thousand pounds and of all the fornications you’ll never commit.”

persey's review

3.0

Huxley's reach exceeded his grasp. A comedy of manners, a comedy of ideas - this is a salmagundi of everything going on among the chattering classes and the bright young things in London of the 20s, with no coherent vision or even story. Amusing enough and occasionally interesting as an idea was worth more than the time it took to read it, but the title says it all.

msand3's review against another edition

2.0

This is the first disappointing work I’ve read from Huxley. While I’m sure it was considered razor-sharp satire in its day, I found the "elite British public school humor" to be grating -- either too dry/obscure for my American sensibilities or else overly-silly in a way that over-compensates for the rest of the novel’s snootiness.

I must admit a bias here: there is a certain type of early-20th-century British comedy of manners that I’ve never been able to enjoy. (Think Evelyn Waugh, Ronald Firbank, Max Beerbohm, etc.) I find that they are so enmeshed in the class they are satirizing that their novels simply become an artifact of that world rather than a work of universal essence. Writers like P.G. Wodehouse or Noël Coward also teeter on the edge of that style, but are often saved because they are, at heart, comedic writers, whereas Huxley, Waugh, et al., are great writers who are trying-on a comic style. The result is that novels like Antic Hay always feel like Terry-Thomas films without Terry-Thomas -- in other words, missing that vital hilarious element that elevates the work above its source material, which otherwise would be insufferable. (The whole point of Terry-Thomas’ marvelous persona is that he is able to take us into that world of upper-class twits and make us laugh at them rather than with them.) Instead of being that kind of work, Antic Hay simply becomes a novel about upper-class twits, which can be alienating and almost-insufferable for someone not of that particular class, culture, and era.

Perhaps I’m being too hard on Huxley, or perhaps I’m just the wrong audience for these kinds of novels. In either case, I just don’t enjoy them.

Thankfully, Huxley would move away from this style because I don’t know if I could take many more novels like this. I had planned to read [b:Crome Yellow|53672|Crome Yellow|Aldous Huxley|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1415575803s/53672.jpg|16335152] soon, but I might skip it in favor of Huxley’s later fiction, which I very much admire.

I must admit a bias here: there is a certain type of early-20th-century British comedy of manners that I’ve never been able to enjoy. (Think Evelyn Waugh, Ronald Firbank, Max Beerbohm, etc.) I find that they are so enmeshed in the class they are satirizing that their novels simply become an artifact of that world rather than a work of universal essence. Writers like P.G. Wodehouse or Noël Coward also teeter on the edge of that style, but are often saved because they are, at heart, comedic writers, whereas Huxley, Waugh, et al., are great writers who are trying-on a comic style. The result is that novels like Antic Hay always feel like Terry-Thomas films without Terry-Thomas -- in other words, missing that vital hilarious element that elevates the work above its source material, which otherwise would be insufferable. (The whole point of Terry-Thomas’ marvelous persona is that he is able to take us into that world of upper-class twits and make us laugh at them rather than with them.) Instead of being that kind of work, Antic Hay simply becomes a novel about upper-class twits, which can be alienating and almost-insufferable for someone not of that particular class, culture, and era.

Perhaps I’m being too hard on Huxley, or perhaps I’m just the wrong audience for these kinds of novels. In either case, I just don’t enjoy them.

Thankfully, Huxley would move away from this style because I don’t know if I could take many more novels like this. I had planned to read [b:Crome Yellow|53672|Crome Yellow|Aldous Huxley|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1415575803s/53672.jpg|16335152] soon, but I might skip it in favor of Huxley’s later fiction, which I very much admire.

gretacwink's review against another edition

4.0

It took me a bit to get into it, but then I was in. It's painfully, wonderfully depressing. There are no silver linings here.

fetanet's review

challenging

informative

slow-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? Character

- Strong character development? No

- Loveable characters? No

- Diverse cast of characters? No

- Flaws of characters a main focus? Yes

2.75

granasys's review against another edition

challenging

funny

sad

slow-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? Character

- Strong character development? No

- Loveable characters? No

- Diverse cast of characters? Yes

- Flaws of characters a main focus? It's complicated

2.0

This book is satirical for sure, but as it makes fun of people who are cynical and hopeless, it was not the right time for me to read it. I became even more miserable, as the characters ran after their own heads, being fake-deep and dramatic.

readingpanda's review

4.0

I'm finding out that just reading Brave New World in high school doesn't really give you any sense of what sort of an author Aldous Huxley was.

Antic Hay is a novel about, essentially, the Lost Generation and their feelings of disaffection and uncertainty in the wake of World War I. A satire, it is at times just poking a bit of fun, at times jabbing viciously. The themes are pretty timeless: disillusionment, the experience of feeling adrift in the world, wondering if what you've wanted for yourself is really worth wanting. The characters are a group of acquaintances who cope with their ennui in a variety of ways - having affairs, becoming unhealthily obsessed with a woman in their social circle, quitting a job, committing to an artistic life, taking pretending to be someone else to new levels.

The interesting things to me about this book were twofold: 1, how easily Huxley switches between humor and despair in the narrative; and 2, how he expressed truths in ways that would be just as valid in today's world with only a few key words changed. For an example, check out the quote at the end of the review. I found the book easy to read and digest, and an interesting look at the time period as well as human nature in general.

Recommended for: people who know that the more things change the more they stay the same, people who need to be reminded that they are not, by any stretch of the imagination, the first to feel unmoored.

Quote: "[W]ould a man with unlimited leisure be free, Mr. Gumbril? I say he would not. Not unless he 'appened to be a man like you or me, Mr. Gumbril, a man of sense, a man of independent judgment. An ordinary man would not be free. Because he wouldn't know how to occupy his leisure except in some way that would be forced on him by other people. People don't know 'how to entertain themselves now; they leave it to other people to do it for them. They swallow what's given them. They 'ave to swallow it, whether they like it or not. Cinemas, newspapers, magazines, gramophones, football matches, wireless, telephones -- take them or leave them, if you want to amuse yourself. The ordinary man can't leave them. He takes; and what's that but slavery?"

Antic Hay is a novel about, essentially, the Lost Generation and their feelings of disaffection and uncertainty in the wake of World War I. A satire, it is at times just poking a bit of fun, at times jabbing viciously. The themes are pretty timeless: disillusionment, the experience of feeling adrift in the world, wondering if what you've wanted for yourself is really worth wanting. The characters are a group of acquaintances who cope with their ennui in a variety of ways - having affairs, becoming unhealthily obsessed with a woman in their social circle, quitting a job, committing to an artistic life, taking pretending to be someone else to new levels.

The interesting things to me about this book were twofold: 1, how easily Huxley switches between humor and despair in the narrative; and 2, how he expressed truths in ways that would be just as valid in today's world with only a few key words changed. For an example, check out the quote at the end of the review. I found the book easy to read and digest, and an interesting look at the time period as well as human nature in general.

Recommended for: people who know that the more things change the more they stay the same, people who need to be reminded that they are not, by any stretch of the imagination, the first to feel unmoored.

Quote: "[W]ould a man with unlimited leisure be free, Mr. Gumbril? I say he would not. Not unless he 'appened to be a man like you or me, Mr. Gumbril, a man of sense, a man of independent judgment. An ordinary man would not be free. Because he wouldn't know how to occupy his leisure except in some way that would be forced on him by other people. People don't know 'how to entertain themselves now; they leave it to other people to do it for them. They swallow what's given them. They 'ave to swallow it, whether they like it or not. Cinemas, newspapers, magazines, gramophones, football matches, wireless, telephones -- take them or leave them, if you want to amuse yourself. The ordinary man can't leave them. He takes; and what's that but slavery?"

2000ace's review

4.0

Antic Hay is a mishmash of various topics on the mind of Aldous Huxley after the end of the first World War. Told from the perspective of a number of different characters, it may suffer from a lack of focus on a plot, but never deviates from Huxley incisive insights into the culture of the time.