Take a photo of a barcode or cover

funny

inspiring

medium-paced

Amazing memoir - poetic, poignant and humorous. She must have been very needy in her 20s and 30s.

medium-paced

This book was beautiful. Some of the letters really moved me. Gorgeous, poetic writing.

Really liked this book - enjoyed her style of writing... and the whole premise of the book. It's not a autobiography, but gives some depth and insight on her thoughts and past experiences. A great find!

MLP is a Leo with a Gemini moon and a Gemini North Node (just like David Bowie). Lively. Soulful. Moody. Impulsive. Eccentric destiny. A graceful elan and at ease in a crowd, with layer upon layer bubbling below the surface.

I'm a Leo sun Pisces moon (like Audrey Hepburn) so I should be too soft for this kind of direct-style of writing, but ... .dkkldfl

(I have to get back to doing some shit I'll finish this later)

I'm a Leo sun Pisces moon (like Audrey Hepburn) so I should be too soft for this kind of direct-style of writing, but ... .dkkldfl

(I have to get back to doing some shit I'll finish this later)

emotional

funny

reflective

sad

medium-paced

This book is written as a series of letters from the author to different men in her life. Lots of people seem to love this book but I struggled with it. A number of times I nearly gave up. Mary-Louise Parker has clearly led an amazing life and she has met some really interesting people but the style of writing just didn't work for me. I liked the last letter to her Dad, her father deserves a story of his own and this sums up my feelings for the book. There are lots of pointers to interesting people and events but frustratingly there is no depth to these stories.

Ms. Parker needs to stick to acting as her writing leaves a lot to be desired. Normally I’m a huge fan of epistolary writing the way this was executed was not done well. Each letter is disjointed and as a reader I had no clue as to whom each letter (of those I read) was written or how that person played a role in Ms. Parker’s life. I ended up putting this down at 25% feeling frustrated and annoyed that I wasted two days trying to get through it.

This review was originally published on Free (Read and) Write

I watched a TED talk just before the 2015 holidays about the way in which literary journals determine what we later read in book form, and because they do we might read less diversely; in particular, we may read less by female authors. The idea is that we want to believe each journal would publish the best works received, but given human bias and reading preferences as to what defines “good,” how likely is that, truly? She encouraged readers to step outside of whatever their reading comfort zones may be, and after watching it (before resorting to audiobooks) I began exclusively reading female authors. And one of my first selections was Dear Mr. You by Mary-Louise Parker.

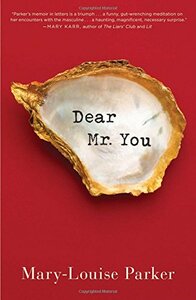

Dear Mr. You is a non-fiction collection of letters to the men of Mary-Louise Parker’s life. Per the book jacket, they “range from a missive to the beloved priest from her childhood to remembrances of former lovers to an homage to a firefighter she briefly encountered to a heartfelt communication with the uncle of the infant daughter she adopted.” And they are brilliant. My mother purchased this for me at Christmas because I love Mary-Louise Parker as an actress (I will discuss Angels in America with anyone who feels like listening to me), but as it turns out she held literary accomplishments far prior to my knowledge of them, including writing in The Riveter, Bust, Esquire, and Bullet. And it’s funny because that’s exactly what this TED talk was about. Sure, Mary-Louise Parker probably could have gotten a book deal without first being taken seriously in the literary world. But she moved through the ranks as a legitimate author, not writing any star-studded biography in the traditional sense, likely because of her movements in that arena first.

Her writing is, for a lack of any great symbolism, beautiful. Breathtaking. She writes the way I want someone to talk to me before I fall asleep every night. And in such a way that makes me think that even if the subject were awful I would have been enthralled with every word all the way to the end.

The first letter to her deceased father ends, “We all miss you something fierce, those of us who wouldn’t exist had you not kept walking when an ordinary person would have fallen to his knees. To convey in any existing language how I miss you isn’t possible. It would be like blue trying to describe the ocean.” And just like that I found myself invested in the emotion of her life while knowing very little about it, scooped up and surrounded by her sadness.

Sometimes I marked passages only for their beauty, as she wrote to Man out of Time: “Scientists can’t agree where speech evolved from so no one can arrive at what makes a particular communication successful. This is something I would never want to know the secret to any more than I would want to know on which day I will die; but its’s a subject I could pull apart for hours without getting bored. I love attempting to describe a thing, but I might love even better the fact that the more words you have available to encode with when you attempt denotation, the farther away you can sail into ambiguity. I could go on about you forever and that might only make you less clear to someone discovering you through my words.” How endlessly I could read and re-read her description of lack of description.

And not only was I wrapped up in her own emotion, surrounded by her beautiful writing, but swallowed up in the memories that her writing inevitably invoked. I thought about the lovers from my drug-induced early 20s in her letters to Risk Taker as she described his responsibility to the audience when he performs because “risk creates intimacy.” Or in her letter to Blue, explaining that he could take “anyone’s idea of modern life and set in on fire decades before anyone dreamed up Burning Man.”

There is so much I want to quote to you! How much is too much? I felt her pain – my own pain – in the disintegration of what felt like it would last forever as she wrote to Popeye, “You said you would love me until you were ashes…I wrote about us while you were away in a notebook that eventually saw the end of us, but the last I wrote about that time was in ink; it was hurried, angry scrawl reading: Time, that cold bastard, with its nearlys and untils. I think, what a shame. Time should weep for having spent me without you.”

I’ll spare you the full paragraph quotation, despite the fact that I want SO BADLY for you to read about how she describes the “less fortunate” and hates the way people write about the “less fortunate” to prove her brilliance to you, but I felt my sister in the description of her adopted child’s uncle. In the way in which she became aware of how intertwined her child would be in families and cultures, both multiple.

This isn’t to say I learned nothing about her life, if your goal were to have a better understanding of Mary-Louise Parker’s life. I learned about college and the way she trained with her movement teacher. I learned about her family’s intricacies, both her parents and children. I learned about her relationship to AIDS in the 80s, the friends she lost and drag queens she loses herself amongst today. Her disgust for those referencing the Bible or the Psychiatric Association to put down the expression of love in those that she loves. About her lovely neighbor in the country who taught her how to live in the country.

But learning about her life clearly wasn’t the purpose. When writing to the physician who saved her life after she became septic and nearly died in the hospital, she told a tangential but significant story about a close friend: “My friend lived next to the World trade Center and I was on the phone with her while she saw people jumping, close enough to see the color of their socks. Her husband urged her to move away form the window. Why are you doing that to yourself, he asked. She said Someone has to watch them.” The raw tangential emotion related to this experience of dying seemed so much more important than the actual experience of dying to Parker. In fact, emotion and the act writing of it seemed to be more thematically important throughout her book than not only her experiences but even the very structure of writing letters to men. How refreshing.

I did, I think it’s worth noting, have a PTSD episode reading about her experiences with physical abuse. The chapter to Cerebrus (funny as perhaps what I would name my own abuser) begins, “This is a once upon a time that happened too much. I’m telling this grim tale to you three. Well, Konnichiwa! Remember me? I’m the gal who sat dumbly in a living room on the Upper East Side while one of your kind lifted me off the couch by my hair in the few seconds it took your wife to go fetch more pistachios. Didn’t you. I put my fingertips to my scalp and they came away bloody as you whispered, ‘Keep your mouth shut about this.’ Didn’t you. Now don’t be frightened. This isn’t an indictment. This is addressed to you, yes, but also to myself, because guess who stood for it?”

In fact, reading this is perhaps the first time I realized I had PTSD. Just this past week, actually, I was speaking to one of my best friends from college, whom I knew when I was dating the man in question, and I told him about the abuse for the first time. It took him a moment to to find his footing in the conversation and grasp what I was revealing. I surprised even myself in that moment with how well I had kept it all a secret. And it was somewhat therapeutic for me to read about Mary-Louise Parker emotionally saving herself in the end. But the chapter is in no way lacking in description or length, and it took a lot of treading through to finally find the salvation. I’m not sure if this is a trigger warning to anyone interested in her work or just me still wading through my own emotional reaction, but like the emotional themes in Mary-Louise Parker’s book, I’m not sure the “what” is something I need to be able to identify right now.

This comfort with lack of identification, lack of “normal” themes, makes me feel almost whimsical about this book when I try to name my response. Down to the last sentence, when she explains why she writes, maybe why she wrote this book, I feel romantic at the thought. About the ability to feel without the detailed description of the thing itself.

Was there anything I read in this that I didn’t like? Sure. The letter to NASA, while clever, felt a little out of place to me. But it doesn’t come close to bringing down my five star rating. Mary-Louise Parker is an amazing writer and an amazingly strong woman, giving glimpses of pure emotional vulnerability without revealing all of the agonizing details of her life. What a feat.

Maybe a part of me loves that although we have lived different lives in different decades I feel a kinship with her. Is that because the design of this book is such that anyone might feel kinship, or do I really purely relate on this level of crazy casual sex I had in college, this question of God, the personal nature of adoption to my life, the impact of medical personnel when feeling disconnected to your body, this pattern of abuse? Or are those just the most important letters I pulled from it? What would you pull?

Or maybe part of it is that this book made me feel like I just completed a therapy session and now I want to write ALL THE LETTERS of my own. To the man who I’m engaged to about why marriage makes me anxious. Is it harder to marry when you’ve created an entirely independent life for yourself at the age of 30? Why doesn’t society allow me to speak about this without implying I’ve chosen the wrong person? And to the man who physically abused me and to the other one who caused even more lasting damage when he did it emotionally. I may suffer through illness now but I will never allow such suffering like that in my life again.

Or maybe it’s just that there are so many parts, so many reasons, to love it.

This post is not to say that The Fifth Season by NK Jemisin wasn’t probably my FAVORITE book that I recently read (it was, and I’ll make sure to tell you all of the reasons why). But the book that hit me the hardest? The one I would have to choose if describing “best?” That award goes to Mary-Louise Parker. Without question.

For more reviews, check out my blog: link: Free (Read and) Write

Or you can follow me!

Instagram

Twitter

Facebook

I watched a TED talk just before the 2015 holidays about the way in which literary journals determine what we later read in book form, and because they do we might read less diversely; in particular, we may read less by female authors. The idea is that we want to believe each journal would publish the best works received, but given human bias and reading preferences as to what defines “good,” how likely is that, truly? She encouraged readers to step outside of whatever their reading comfort zones may be, and after watching it (before resorting to audiobooks) I began exclusively reading female authors. And one of my first selections was Dear Mr. You by Mary-Louise Parker.

Dear Mr. You is a non-fiction collection of letters to the men of Mary-Louise Parker’s life. Per the book jacket, they “range from a missive to the beloved priest from her childhood to remembrances of former lovers to an homage to a firefighter she briefly encountered to a heartfelt communication with the uncle of the infant daughter she adopted.” And they are brilliant. My mother purchased this for me at Christmas because I love Mary-Louise Parker as an actress (I will discuss Angels in America with anyone who feels like listening to me), but as it turns out she held literary accomplishments far prior to my knowledge of them, including writing in The Riveter, Bust, Esquire, and Bullet. And it’s funny because that’s exactly what this TED talk was about. Sure, Mary-Louise Parker probably could have gotten a book deal without first being taken seriously in the literary world. But she moved through the ranks as a legitimate author, not writing any star-studded biography in the traditional sense, likely because of her movements in that arena first.

Her writing is, for a lack of any great symbolism, beautiful. Breathtaking. She writes the way I want someone to talk to me before I fall asleep every night. And in such a way that makes me think that even if the subject were awful I would have been enthralled with every word all the way to the end.

The first letter to her deceased father ends, “We all miss you something fierce, those of us who wouldn’t exist had you not kept walking when an ordinary person would have fallen to his knees. To convey in any existing language how I miss you isn’t possible. It would be like blue trying to describe the ocean.” And just like that I found myself invested in the emotion of her life while knowing very little about it, scooped up and surrounded by her sadness.

Sometimes I marked passages only for their beauty, as she wrote to Man out of Time: “Scientists can’t agree where speech evolved from so no one can arrive at what makes a particular communication successful. This is something I would never want to know the secret to any more than I would want to know on which day I will die; but its’s a subject I could pull apart for hours without getting bored. I love attempting to describe a thing, but I might love even better the fact that the more words you have available to encode with when you attempt denotation, the farther away you can sail into ambiguity. I could go on about you forever and that might only make you less clear to someone discovering you through my words.” How endlessly I could read and re-read her description of lack of description.

And not only was I wrapped up in her own emotion, surrounded by her beautiful writing, but swallowed up in the memories that her writing inevitably invoked. I thought about the lovers from my drug-induced early 20s in her letters to Risk Taker as she described his responsibility to the audience when he performs because “risk creates intimacy.” Or in her letter to Blue, explaining that he could take “anyone’s idea of modern life and set in on fire decades before anyone dreamed up Burning Man.”

There is so much I want to quote to you! How much is too much? I felt her pain – my own pain – in the disintegration of what felt like it would last forever as she wrote to Popeye, “You said you would love me until you were ashes…I wrote about us while you were away in a notebook that eventually saw the end of us, but the last I wrote about that time was in ink; it was hurried, angry scrawl reading: Time, that cold bastard, with its nearlys and untils. I think, what a shame. Time should weep for having spent me without you.”

I’ll spare you the full paragraph quotation, despite the fact that I want SO BADLY for you to read about how she describes the “less fortunate” and hates the way people write about the “less fortunate” to prove her brilliance to you, but I felt my sister in the description of her adopted child’s uncle. In the way in which she became aware of how intertwined her child would be in families and cultures, both multiple.

This isn’t to say I learned nothing about her life, if your goal were to have a better understanding of Mary-Louise Parker’s life. I learned about college and the way she trained with her movement teacher. I learned about her family’s intricacies, both her parents and children. I learned about her relationship to AIDS in the 80s, the friends she lost and drag queens she loses herself amongst today. Her disgust for those referencing the Bible or the Psychiatric Association to put down the expression of love in those that she loves. About her lovely neighbor in the country who taught her how to live in the country.

But learning about her life clearly wasn’t the purpose. When writing to the physician who saved her life after she became septic and nearly died in the hospital, she told a tangential but significant story about a close friend: “My friend lived next to the World trade Center and I was on the phone with her while she saw people jumping, close enough to see the color of their socks. Her husband urged her to move away form the window. Why are you doing that to yourself, he asked. She said Someone has to watch them.” The raw tangential emotion related to this experience of dying seemed so much more important than the actual experience of dying to Parker. In fact, emotion and the act writing of it seemed to be more thematically important throughout her book than not only her experiences but even the very structure of writing letters to men. How refreshing.

I did, I think it’s worth noting, have a PTSD episode reading about her experiences with physical abuse. The chapter to Cerebrus (funny as perhaps what I would name my own abuser) begins, “This is a once upon a time that happened too much. I’m telling this grim tale to you three. Well, Konnichiwa! Remember me? I’m the gal who sat dumbly in a living room on the Upper East Side while one of your kind lifted me off the couch by my hair in the few seconds it took your wife to go fetch more pistachios. Didn’t you. I put my fingertips to my scalp and they came away bloody as you whispered, ‘Keep your mouth shut about this.’ Didn’t you. Now don’t be frightened. This isn’t an indictment. This is addressed to you, yes, but also to myself, because guess who stood for it?”

In fact, reading this is perhaps the first time I realized I had PTSD. Just this past week, actually, I was speaking to one of my best friends from college, whom I knew when I was dating the man in question, and I told him about the abuse for the first time. It took him a moment to to find his footing in the conversation and grasp what I was revealing. I surprised even myself in that moment with how well I had kept it all a secret. And it was somewhat therapeutic for me to read about Mary-Louise Parker emotionally saving herself in the end. But the chapter is in no way lacking in description or length, and it took a lot of treading through to finally find the salvation. I’m not sure if this is a trigger warning to anyone interested in her work or just me still wading through my own emotional reaction, but like the emotional themes in Mary-Louise Parker’s book, I’m not sure the “what” is something I need to be able to identify right now.

This comfort with lack of identification, lack of “normal” themes, makes me feel almost whimsical about this book when I try to name my response. Down to the last sentence, when she explains why she writes, maybe why she wrote this book, I feel romantic at the thought. About the ability to feel without the detailed description of the thing itself.

Was there anything I read in this that I didn’t like? Sure. The letter to NASA, while clever, felt a little out of place to me. But it doesn’t come close to bringing down my five star rating. Mary-Louise Parker is an amazing writer and an amazingly strong woman, giving glimpses of pure emotional vulnerability without revealing all of the agonizing details of her life. What a feat.

Maybe a part of me loves that although we have lived different lives in different decades I feel a kinship with her. Is that because the design of this book is such that anyone might feel kinship, or do I really purely relate on this level of crazy casual sex I had in college, this question of God, the personal nature of adoption to my life, the impact of medical personnel when feeling disconnected to your body, this pattern of abuse? Or are those just the most important letters I pulled from it? What would you pull?

Or maybe part of it is that this book made me feel like I just completed a therapy session and now I want to write ALL THE LETTERS of my own. To the man who I’m engaged to about why marriage makes me anxious. Is it harder to marry when you’ve created an entirely independent life for yourself at the age of 30? Why doesn’t society allow me to speak about this without implying I’ve chosen the wrong person? And to the man who physically abused me and to the other one who caused even more lasting damage when he did it emotionally. I may suffer through illness now but I will never allow such suffering like that in my life again.

Or maybe it’s just that there are so many parts, so many reasons, to love it.

This post is not to say that The Fifth Season by NK Jemisin wasn’t probably my FAVORITE book that I recently read (it was, and I’ll make sure to tell you all of the reasons why). But the book that hit me the hardest? The one I would have to choose if describing “best?” That award goes to Mary-Louise Parker. Without question.

For more reviews, check out my blog: link: Free (Read and) Write

Or you can follow me!