Take a photo of a barcode or cover

This devastating book is almost unbearable to read, but worth it! Here's my review.

http://www.washingtonindependentreviewofbooks.com/bookreview/the-druggist-of-auschwitz-a-documentary-novel/

If only The Druggist of Auschwitz were fiction. The book’s sole imaginary character, however, is the narrator, Adam Salmen. Said to be the “last Jew of Schässburg,” (now Sigişoara, Romania), Adam’s occasional commentary coils through ghastly fact.

The core of the book is Dieter Schlesak’s arrangement of witness testimony and historical research about the 1963-1965 Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, with Victor Capesius as one of the defendants. Capesius, the chief pharmacist at Auschwitz, is the “druggist” of the title. Through Capesius and his comrades, Schlesak documents the Nazis’ grotesque perversion of the Hippocratic Oath.

In our world, the words “pharmacist” and “druggist” connote therapy and healing. But in the hell that was Auschwitz, it was doctors and other health professionals, led by Joseph Mengele, who ensured the efficiency of the death machine. Nazi medical professionals stood on the ramp as the cattle cars rolled in bearing over a million Jews and 20,000 Gypsies from across Europe. They made the selections on who would live and who would die. Nazi dentists pulled the teeth with gold crowns out of the mouths of people on their way into the gas chamber. Nazi “medics” poured the canisters of Zyklon B into the sealed chambers of death. Nazi doctors injected chloroform into the hearts of adults and children, especially twins, to kill them for onsite medical experimentation.

As Schlesak painstakingly catalogues, any number of characteristics were immediate qualifications for “selection” to the gas chamber – scars and bodily imperfections, old age, youth, infancy, pregnancy, being female, sickness, broken limbs, and most important – the whim of the selector on duty. Within the small minority of prisoners allowed to live, Jewish medical professionals had a slight edge. If they had the foresight to speak up as they arrived, they might be chosen for jobs such as cleaning the gold from victims’ teeth. Or, in the case of Miklós Nyiszli, briefly profiled toward the end of the book, performing dissections on Dr. Mengele’s newly murdered patients.

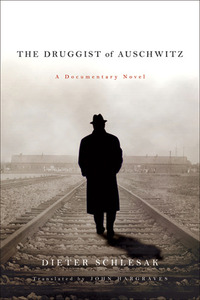

The Druggist of Auschwitz is interspersed with photographs of witnesses, Capesius, and the death camp itself. The inclusion of photographs resonates with the work of another German writer straddling the line between fact and fiction – W. G. Sebald, whose Austerlitz reads like a memoir in which the author purports to unearth his long repressed experiences flowing from the British kinder transport. In contrast to Schlesak, however, Sebald creates a parallel world that is credible because of its attention to historical and psychological detail.

The Druggist of Auschwitz recounts unadorned truth. Here the devil is, in fact, in the details. In the strict punctuality of the elevator operators removing the newly gassed bodies (they were not always dead) for incineration, to make room for the next transport. In the daughter, designated to live, who joins her mother in the gas chamber so that her mother will not die alone. In the Red Cross trucks, carrying canisters of Zyklon B to the gas chamber. In the organized killings of hundreds against the “Black Wall,” where it was determined that the shooters would be less upset if the guns had silencers on them.

In portraying the leisure activities of the SS officers at Auschwitz, Schlesak quotes Roland Albert, his distant relative. “As a sideline I was a religion teacher, when my guard duty allowed. My wife taught music in the main school. … It was life like anywhere else. We planted a vegetable garden, kept bees, planted flowers, went hunting and fishing, there were afternoon coffee parties, birthdays, Christmas parties with Commandant H[ess].”

In detailing the meticulous record keeping, Schlesak shows the log listing each train and its number of victims, with Capesius’ annotations in the margins. He enumerates the cost of a canister of Zyklon B. Witnesses speak to the sorting of the possessions of all who entered the gates, whether or not they were gassed – clothing and shoes in one place, currency in another, gold and jewels somewhere else. A centerpiece of Capesius’ trial was the question of his significant postwar wealth. Capesius vigorously denied that his riches came from Auschwitz victims.

What is new here? Schlesak is certainly not the first to document this destruction of humanity. As Primo Levi wrote in Survival in Auschwitz, “Then for the first time we became aware that our language lacks words to express this offence, the demolition of a man. … Nothing belongs to us anymore; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand.” Nor is Schlesak the first to chronicle the complete disconnection between the perpetrators’ actions and their later disavowal of personal responsibility. There can be no colder account of this phenomenon than Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. What is new in The Druggist of Auschwitz is the use of Victor Capesius – an unknown figure to most readers – to remind us once again of man’s infinite capacity for evil. Schlesak does a masterful job of intermingling eyewitness testimony of Capesius’ role in the selection and killing process with Capesius’ revisionist account, partly obtained from interviews that Schlesak conducted himself.

Another innovation is the organization of the book itself. It seems beside the point to consider the literary merits of such horrifying material, but the title begs the question – Is this a novel? Schlesak constructs the book in nine parts, with some chapter headings reading like a history text: “The Auschwitz Dispensary,” “The German Obsession with Racial ‘Purity’ and the German Language as a Cure.” Carefully ordered historical material ensures that no group is spared from harsh examination. A German populace trained to obey authority enabled the scale and efficiency of the killing. But there are other human realities as well. What did it take to survive? Adam, the fictional narrator, is a “Sonderkommando” (German for “Special Unit”) – prisoners considered able bodied at selection who were given the job of removing bodies from the crematorium. These Jewish prisoners were intimately involved with the killing, although not themselves the killers. Adam’s terse remarks buttress the testimony of real life Sonderkommandos who speak about the relentlessness of the killing, and their role in the “clean up.” Using factual data, Schlesak exposes the role of Jewish councils in guaranteeing that the lists of Jews in their respective communities were accurate before turning over this information to the Nazis, enabling Jews to be rounded up with ease. On the flip side, he considers the madness of Hitler’s relatives as a factor in Hitler’s insane drive to disavow his past: he was not German (he was Austrian); he was not Aryan (he likely had Jewish ancestry); he was not light skinned or blond.

If a historian’s role is to document the past’s realities so that future generations can see the truth, then this is a historical work. If a fiction writer’s role is to expose the truths that motivate human activity, then this is a work of fiction. In the end, does the distinction matter? Schlesak has succeeded in organizing this confronting material in a way that compels us to read it. The power is in making the unbelievable believable.

It is difficult to understand how life goes on after Auschwitz. And yet it does. There are authors like Viktor Frankl and the recently deceased Arnošt Lustig who found a calling in identifying and recording the humanity within the horror. And then there are others, like Simon Wiesenthal, who made it a profession to hunt Nazis, but still took the time to explore the possibilities and limits of forgiveness in The Sunflower.

We cannot and should not forget. The Druggist of Auschwitz makes an important contribution toward that end, with John Hargrave’s translation communicating this raw material in a way that once again forces us to examine how ordinary people can descend to such terrifying depths.

Martha Toll is Executive Director of the Butler Family Fund, a nationwide philanthropy focused on ending homelessness and the death penalty. She writes novels and has been featured as a book commentator on NPR.

http://www.washingtonindependentreviewofbooks.com/bookreview/the-druggist-of-auschwitz-a-documentary-novel/

If only The Druggist of Auschwitz were fiction. The book’s sole imaginary character, however, is the narrator, Adam Salmen. Said to be the “last Jew of Schässburg,” (now Sigişoara, Romania), Adam’s occasional commentary coils through ghastly fact.

The core of the book is Dieter Schlesak’s arrangement of witness testimony and historical research about the 1963-1965 Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, with Victor Capesius as one of the defendants. Capesius, the chief pharmacist at Auschwitz, is the “druggist” of the title. Through Capesius and his comrades, Schlesak documents the Nazis’ grotesque perversion of the Hippocratic Oath.

In our world, the words “pharmacist” and “druggist” connote therapy and healing. But in the hell that was Auschwitz, it was doctors and other health professionals, led by Joseph Mengele, who ensured the efficiency of the death machine. Nazi medical professionals stood on the ramp as the cattle cars rolled in bearing over a million Jews and 20,000 Gypsies from across Europe. They made the selections on who would live and who would die. Nazi dentists pulled the teeth with gold crowns out of the mouths of people on their way into the gas chamber. Nazi “medics” poured the canisters of Zyklon B into the sealed chambers of death. Nazi doctors injected chloroform into the hearts of adults and children, especially twins, to kill them for onsite medical experimentation.

As Schlesak painstakingly catalogues, any number of characteristics were immediate qualifications for “selection” to the gas chamber – scars and bodily imperfections, old age, youth, infancy, pregnancy, being female, sickness, broken limbs, and most important – the whim of the selector on duty. Within the small minority of prisoners allowed to live, Jewish medical professionals had a slight edge. If they had the foresight to speak up as they arrived, they might be chosen for jobs such as cleaning the gold from victims’ teeth. Or, in the case of Miklós Nyiszli, briefly profiled toward the end of the book, performing dissections on Dr. Mengele’s newly murdered patients.

The Druggist of Auschwitz is interspersed with photographs of witnesses, Capesius, and the death camp itself. The inclusion of photographs resonates with the work of another German writer straddling the line between fact and fiction – W. G. Sebald, whose Austerlitz reads like a memoir in which the author purports to unearth his long repressed experiences flowing from the British kinder transport. In contrast to Schlesak, however, Sebald creates a parallel world that is credible because of its attention to historical and psychological detail.

The Druggist of Auschwitz recounts unadorned truth. Here the devil is, in fact, in the details. In the strict punctuality of the elevator operators removing the newly gassed bodies (they were not always dead) for incineration, to make room for the next transport. In the daughter, designated to live, who joins her mother in the gas chamber so that her mother will not die alone. In the Red Cross trucks, carrying canisters of Zyklon B to the gas chamber. In the organized killings of hundreds against the “Black Wall,” where it was determined that the shooters would be less upset if the guns had silencers on them.

In portraying the leisure activities of the SS officers at Auschwitz, Schlesak quotes Roland Albert, his distant relative. “As a sideline I was a religion teacher, when my guard duty allowed. My wife taught music in the main school. … It was life like anywhere else. We planted a vegetable garden, kept bees, planted flowers, went hunting and fishing, there were afternoon coffee parties, birthdays, Christmas parties with Commandant H[ess].”

In detailing the meticulous record keeping, Schlesak shows the log listing each train and its number of victims, with Capesius’ annotations in the margins. He enumerates the cost of a canister of Zyklon B. Witnesses speak to the sorting of the possessions of all who entered the gates, whether or not they were gassed – clothing and shoes in one place, currency in another, gold and jewels somewhere else. A centerpiece of Capesius’ trial was the question of his significant postwar wealth. Capesius vigorously denied that his riches came from Auschwitz victims.

What is new here? Schlesak is certainly not the first to document this destruction of humanity. As Primo Levi wrote in Survival in Auschwitz, “Then for the first time we became aware that our language lacks words to express this offence, the demolition of a man. … Nothing belongs to us anymore; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand.” Nor is Schlesak the first to chronicle the complete disconnection between the perpetrators’ actions and their later disavowal of personal responsibility. There can be no colder account of this phenomenon than Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. What is new in The Druggist of Auschwitz is the use of Victor Capesius – an unknown figure to most readers – to remind us once again of man’s infinite capacity for evil. Schlesak does a masterful job of intermingling eyewitness testimony of Capesius’ role in the selection and killing process with Capesius’ revisionist account, partly obtained from interviews that Schlesak conducted himself.

Another innovation is the organization of the book itself. It seems beside the point to consider the literary merits of such horrifying material, but the title begs the question – Is this a novel? Schlesak constructs the book in nine parts, with some chapter headings reading like a history text: “The Auschwitz Dispensary,” “The German Obsession with Racial ‘Purity’ and the German Language as a Cure.” Carefully ordered historical material ensures that no group is spared from harsh examination. A German populace trained to obey authority enabled the scale and efficiency of the killing. But there are other human realities as well. What did it take to survive? Adam, the fictional narrator, is a “Sonderkommando” (German for “Special Unit”) – prisoners considered able bodied at selection who were given the job of removing bodies from the crematorium. These Jewish prisoners were intimately involved with the killing, although not themselves the killers. Adam’s terse remarks buttress the testimony of real life Sonderkommandos who speak about the relentlessness of the killing, and their role in the “clean up.” Using factual data, Schlesak exposes the role of Jewish councils in guaranteeing that the lists of Jews in their respective communities were accurate before turning over this information to the Nazis, enabling Jews to be rounded up with ease. On the flip side, he considers the madness of Hitler’s relatives as a factor in Hitler’s insane drive to disavow his past: he was not German (he was Austrian); he was not Aryan (he likely had Jewish ancestry); he was not light skinned or blond.

If a historian’s role is to document the past’s realities so that future generations can see the truth, then this is a historical work. If a fiction writer’s role is to expose the truths that motivate human activity, then this is a work of fiction. In the end, does the distinction matter? Schlesak has succeeded in organizing this confronting material in a way that compels us to read it. The power is in making the unbelievable believable.

It is difficult to understand how life goes on after Auschwitz. And yet it does. There are authors like Viktor Frankl and the recently deceased Arnošt Lustig who found a calling in identifying and recording the humanity within the horror. And then there are others, like Simon Wiesenthal, who made it a profession to hunt Nazis, but still took the time to explore the possibilities and limits of forgiveness in The Sunflower.

We cannot and should not forget. The Druggist of Auschwitz makes an important contribution toward that end, with John Hargrave’s translation communicating this raw material in a way that once again forces us to examine how ordinary people can descend to such terrifying depths.

Martha Toll is Executive Director of the Butler Family Fund, a nationwide philanthropy focused on ending homelessness and the death penalty. She writes novels and has been featured as a book commentator on NPR.

It was a good book. I didn't particularly like the 'fiction' mixed in with the documentary part - I thought I would but in the end it just didn't work for me. The book comes off as quite wordy at times. I know a lot of it is testimony, but some of it was unnecessary. The focal point was lost at times, I found. It was still a quite moving book and it truly showed the horrific side of the Holocaust, but I just think I would have liked it more if it was a straight documentary novel.

I have always had a deep yearning to learn anything I could about WWII since I found out my great Grandfather fought in it. When I found Elie Wiesel's infamous "Night" my senior year of high school, all literature pertaining to the Jewish experience during the war became a quiet fixation. Being a privileged child growing up in the Southeastern US, it was hard to fathom that such monstrosities happened and that my fellow human beings were a part of it all. Reading this book has opened up a new perspective for me since it contains the transcriptions from the Frankfurt trials. I enjoyed reading Schlesak's artful blending of the fictional storyline with Adam and the horrible reality of narratives from victims and SS alike. This book tries to help us understand the actions of humankind, and to comprehend the horrific justifications that we are capable of.

3.5 stars. At times the mix of actual interviews and testimony, with the fictional character got a bit jumbled. But otherwise a beautiful, horrible very difficult to read book.

A Mature, Moving Novel

The Druggist of Auschwitz:A Documentary Novel, is a mature read, despite the fact that some of it is fiction. While I did enjoy the book as a whole and the knowledge I received from it, I would not recommend it to young children. With that said; I came upon this book by accident, as I browsed through the shelves at my local library. I was curious and excited (I'm a little geeky) and couldn't wait to start reading. However, when I first started reading it and flipping through the pages, I almost put it back simply because it is very hard to follow, at first. After reading the inside flap and getting the back story (*note:you need to do this first in order to fully be able to understand the book) I decided to give it another try...and then another. And while this is the type of book that requires full focus, I am so glad that I committed to it. I'll admit, I was horrified by the knowledge that I received about Auschwitz, Dr. Capesius (who is known as the Druggist of Auschwitz and who this book manly focuses on) and the unspeakable torture that all of victims endured. Despite this though, I was interested in the testimonies of the victims during the trials, as well as the cultural view that the author offered on those who committed these horrible acts, and still viewed as though they had done nothing wrong. I would recommend that anyone who is thinking of giving this book a try, to do so, it is truly an interesting read.

The Druggist of Auschwitz:A Documentary Novel, is a mature read, despite the fact that some of it is fiction. While I did enjoy the book as a whole and the knowledge I received from it, I would not recommend it to young children. With that said; I came upon this book by accident, as I browsed through the shelves at my local library. I was curious and excited (I'm a little geeky) and couldn't wait to start reading. However, when I first started reading it and flipping through the pages, I almost put it back simply because it is very hard to follow, at first. After reading the inside flap and getting the back story (*note:you need to do this first in order to fully be able to understand the book) I decided to give it another try...and then another. And while this is the type of book that requires full focus, I am so glad that I committed to it. I'll admit, I was horrified by the knowledge that I received about Auschwitz, Dr. Capesius (who is known as the Druggist of Auschwitz and who this book manly focuses on) and the unspeakable torture that all of victims endured. Despite this though, I was interested in the testimonies of the victims during the trials, as well as the cultural view that the author offered on those who committed these horrible acts, and still viewed as though they had done nothing wrong. I would recommend that anyone who is thinking of giving this book a try, to do so, it is truly an interesting read.

This was a horribly disturbing and moving book about the reality of life in Auschwitz. While the author did take some liberties by adding in the fictional character of "Adam", I think it added more depth. The main content of the book is excerpts of the Auschwitz trial, focusing on the prosecution of Dr.Capesius (for whom the book is named) and interview with other SS officials. The banality of how the subjects speak of the things they saw, coupled with vivid and detailed descriptions of every day life from a prisoners point of view, is what makes this book so disturbing.

And while these images will haunt me for a long time, I do recommend this book. Everyone needs to see what humans are capable of when they blindly follow orders.

And while these images will haunt me for a long time, I do recommend this book. Everyone needs to see what humans are capable of when they blindly follow orders.

"A human being, like a dog, can get used to anything!"

So says Adam Salmen, a fictional narrator in Dieter Schlesak's The Druggist of Auschwitz: A Documentary Novel. But what Salmen and others imprisoned in the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II got "used to" is staggering, so much so that it continues to shock the world decades later. Children grabbed by their legs and smashed into walls. Infants catapulted alive into trenches in which dozens of corpses have been set afire. Mussulmen, inmates so emaciated and starved they are a sort of an "undead creature, ... a human being past tense."

Sadly, that is not the imagination of fiction. Schlesak takes a unique approach to literary nonfiction. The vast majority of the book consists of excerpts from actual trial transcripts and interviews. Salmen, "the last Jew of Schlossberg," Romania, serves as a somewhat ubiquitous witness, personifying various details. As in the original German edition, his and other fictional narration appear in italic while roman type is used for material taken from the second Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt from 1963 to 1965 and interviews.

Adam is a member of the Sonderkommando, prisoners forced to dispose of the mountains of corpses, as well as an inmate resistance group. But Adam is not the real focus of The Druggist of Auschwitz. Instead, the book is built upon the 1944 deportations of thousands upon thousands of Romanian and Hungarian Jews to Auschitz and Capesius, a drug salesman from Transylvania before the war. Once Romania joined the Axis, ethnic Germans in the Romanian army like Capesius were transferred to the Waffen-SS. Capesius eventually became the camp pharmacist at Auschwitz and was present when his fellow countrymen arrived at the camp. These focal points allow Schlesak to provide the perspective of both the persecutors and the persecuted.

Many of the details of what occurred at the camp are, as would be expected, appalling. In addition to storing drugs and some of the Zyklon B used in the gas chambers, Capesius' workplace contained trunks with thousands of gold teeth pulled from victims, many with bits of flesh still attached. There was widespread belief that his post-war wealth stemmed from his access to these teeth. Yet what is perhaps most shocking is the capacity Capesius and others have to feel no guilt or blame for what transpired. Dozens of witnesses testified that during the Hungarian transports, Capesius was among the SS officers involved in the "selection process" on the loading ramps, directing people either toward the labor camp or the gas chambers. Both at trial and later, Capesius vehemently denies this, just as he denies having any role in handling the Zyklon B. For him, the trials are simply about saving his own life. The suffering, the victims, the inhumanity are lost, secondary details in a miasma of dates, data and denial.

Capesius is far from alone in possessing that inability to feel guilt or be bothered by his conscience. And this goes far beyond the claim that "I was just following orders." Thus, some involved in the selection process would claim they actually "saved" the Jews they pointed toward the labor camp instead of the crematoria. Auschwitz also was where Dr. Josef Mengele and others performed experiments on prisoners. Yet within weeks of the end of the war, the chief of the Auschwitz doctors wrote that "we can stand before God and man with the clearest consciences. ... What crime have I committed? I really do not know."

Translated by John Hargraves, The Druggist of Auschwitz was first published in German in 2006. It made its initial U.S. appearance this year and is now out in a paperback edition. It can feel a bit choppy, jumping in time and location and occasionally more meandering than linear. This is magnified by at times almost abrupt transitions from trial transcripts to Schlesak's interviews to his own observations. Although initially a bit distracting, the reader will adapt to the use of italic and roman text in the narration. In fact, there are a couple literary nonfiction books over the last year or so where I wish the author had been required to distinguish between fact and invention.

Ultimately, these flaws are inconsequential in the context of the work and what it reveals about the human ability to absolve one's conscience or oneself. In fact, Adam observes, that may be almost as bad as the crimes themselves -- "it was precisely this ability that made Auschwitz possible in the first place!"

(Originally posted at A Progressive on the Prairie.)

So says Adam Salmen, a fictional narrator in Dieter Schlesak's The Druggist of Auschwitz: A Documentary Novel. But what Salmen and others imprisoned in the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II got "used to" is staggering, so much so that it continues to shock the world decades later. Children grabbed by their legs and smashed into walls. Infants catapulted alive into trenches in which dozens of corpses have been set afire. Mussulmen, inmates so emaciated and starved they are a sort of an "undead creature, ... a human being past tense."

Sadly, that is not the imagination of fiction. Schlesak takes a unique approach to literary nonfiction. The vast majority of the book consists of excerpts from actual trial transcripts and interviews. Salmen, "the last Jew of Schlossberg," Romania, serves as a somewhat ubiquitous witness, personifying various details. As in the original German edition, his and other fictional narration appear in italic while roman type is used for material taken from the second Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt from 1963 to 1965 and interviews.

Adam is a member of the Sonderkommando, prisoners forced to dispose of the mountains of corpses, as well as an inmate resistance group. But Adam is not the real focus of The Druggist of Auschwitz. Instead, the book is built upon the 1944 deportations of thousands upon thousands of Romanian and Hungarian Jews to Auschitz and Capesius, a drug salesman from Transylvania before the war. Once Romania joined the Axis, ethnic Germans in the Romanian army like Capesius were transferred to the Waffen-SS. Capesius eventually became the camp pharmacist at Auschwitz and was present when his fellow countrymen arrived at the camp. These focal points allow Schlesak to provide the perspective of both the persecutors and the persecuted.

Many of the details of what occurred at the camp are, as would be expected, appalling. In addition to storing drugs and some of the Zyklon B used in the gas chambers, Capesius' workplace contained trunks with thousands of gold teeth pulled from victims, many with bits of flesh still attached. There was widespread belief that his post-war wealth stemmed from his access to these teeth. Yet what is perhaps most shocking is the capacity Capesius and others have to feel no guilt or blame for what transpired. Dozens of witnesses testified that during the Hungarian transports, Capesius was among the SS officers involved in the "selection process" on the loading ramps, directing people either toward the labor camp or the gas chambers. Both at trial and later, Capesius vehemently denies this, just as he denies having any role in handling the Zyklon B. For him, the trials are simply about saving his own life. The suffering, the victims, the inhumanity are lost, secondary details in a miasma of dates, data and denial.

Capesius is far from alone in possessing that inability to feel guilt or be bothered by his conscience. And this goes far beyond the claim that "I was just following orders." Thus, some involved in the selection process would claim they actually "saved" the Jews they pointed toward the labor camp instead of the crematoria. Auschwitz also was where Dr. Josef Mengele and others performed experiments on prisoners. Yet within weeks of the end of the war, the chief of the Auschwitz doctors wrote that "we can stand before God and man with the clearest consciences. ... What crime have I committed? I really do not know."

Translated by John Hargraves, The Druggist of Auschwitz was first published in German in 2006. It made its initial U.S. appearance this year and is now out in a paperback edition. It can feel a bit choppy, jumping in time and location and occasionally more meandering than linear. This is magnified by at times almost abrupt transitions from trial transcripts to Schlesak's interviews to his own observations. Although initially a bit distracting, the reader will adapt to the use of italic and roman text in the narration. In fact, there are a couple literary nonfiction books over the last year or so where I wish the author had been required to distinguish between fact and invention.

Ultimately, these flaws are inconsequential in the context of the work and what it reveals about the human ability to absolve one's conscience or oneself. In fact, Adam observes, that may be almost as bad as the crimes themselves -- "it was precisely this ability that made Auschwitz possible in the first place!"

(Originally posted at A Progressive on the Prairie.)

One of the most unique books I’ve ever read. Promoted as a “documentary novel,” the author weaves a fictional narrative into the trial testimonies and personal interviews with those convicted of war crimes at Auschwitz. I never fully bought into the sudden transitions into fiction/non-fiction throughout the book, but I also recognize that a lot of the choppiness could be due to translation barriers. What I did appreciate about this book was the less discussed stories of what happened to the terrible individuals who thought they could get away with their crimes. This story tells how the doctor who ordered the gassing of thousands hid in plain sight until the mid 50s, but was finally sentenced and tried in the years after. This book is obviously not a happy one, and required me to read in a way I’m not accustomed to, but also provided me with information not typically present in World War II books. It’s worth a try if you’re willing to commit!

This book was about a third full of details regarding one druggist who served at Auschwitz and then returned to run a pharmacy. The rest though is full of interesting and haunting descriptions of life and death at the camps. I read and keep books like these because I feel it is important for us to remember what happened so it will never happen again.

I don't think it's ever taken me so long to read a book I enjoyed in my entire life. So many times I had to put the book down to cry or even to stop reading because the book felt heavy on my soul. Masterfully creative with the fictional voice of Adam and the true pieces of courtroom testimonies and real life interviews, this book portrays a piece of Auschwitz like never heard before.