Take a photo of a barcode or cover

13 reviews for:

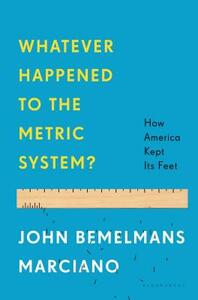

Whatever Happened to the Metric System?: How America Kept Its Feet

John Bemelmans Marciano

13 reviews for:

Whatever Happened to the Metric System?: How America Kept Its Feet

John Bemelmans Marciano

More interesting than I thought it would be, as it describes America's journey to not only imperial measures but also our currency and time zones. The story doesn't just focus on the U.S. either, also discussing events in the rest of the world and their influence on our decisions. Everyone should read this book!

Framing the push for standardization (yes, the book goes beyond metric, although it never stops being the primary focus) in the light of politics makes this a much more fascinating read than one would normally expect from something about, well, measuring. The use of standardized measures, in particular the decimal-based meter, to support globalization/democracy/science (for those of you not in the know, the metric system saw its first big adoption as part of the French Revolution and then "antimetricism" to support isolationism/individuality/common sense, would not have occurred to me, especially since as an American with a background in science I think imperial measurements are arbitrary as shit...and yet can't help using them because that's what I grew up on. I would call Marciano's treatment of both sides reasonably objective; he doesn't mock Dewey's devotion to simplified spelling or Brand's near-fanatical hatred of SI units, especially since opposed counterparts are always to be found. Perhaps this stems in part from the pragmatic view in the last chapter (albeit a little marred by the bit on preserving diversity by refusing to go metric; I read the book's framing as standardization of measures being a reflection of political leanings, not vice versa).

A quick, fun read about the weirdness of America's weights and measures, and how we kept them in the face of pressure to go metric.

Although it's not entirely about that. It begins with the world's differing measuring systems - weights, lengths, volume, money and time. It's a long buildup explain the histories, twists and turns.

But some interesting factoids: America was the first nation to deploy a truly successful decimal system: money. Almost nothing else the public actively does is decimal, in the base-10 sense. Ultimately, Americans didn't see the need outside of science and other technical types.

But we do run our 10Ks and buy our liters of soda and take our milligrams of aspirin, while buying cloth in yards and a gallon of milk. In an odd way, we've done what we usually do: subsume for our own purposes.

Although it's not entirely about that. It begins with the world's differing measuring systems - weights, lengths, volume, money and time. It's a long buildup explain the histories, twists and turns.

But some interesting factoids: America was the first nation to deploy a truly successful decimal system: money. Almost nothing else the public actively does is decimal, in the base-10 sense. Ultimately, Americans didn't see the need outside of science and other technical types.

But we do run our 10Ks and buy our liters of soda and take our milligrams of aspirin, while buying cloth in yards and a gallon of milk. In an odd way, we've done what we usually do: subsume for our own purposes.

More than meets the title. It is really a history book detailing the history of the metric system over the past 200+ years. Jefferson was a proponent, for example. But the book also veers into the history of international postage stamps, the calendar, decimal coinage, standard time zones, etc. It isn't until the last chapter that the author really begins to answer the question posed. And in the end (spoiler alert) he concludes that while the metric system is used quite a bit in the US (e.g. for packaging sold in stores), it doesn't really matter that we are coexisting with two systems, just like we coexist without a single international language (which he also addresses in the book). Just like Britain still drives on the left unlike the rest of the world. Perhaps that is just part of living in a diverse world and that's OK.

While the title of the book makes it seem like it primarily deals with the U.S. and the Metric system, it really covers quite a bit of the history of global weights and measures, but it does so essentially from the start of the U.S. as a nation and uses the U.S. as the central framing device. The majority of the book deals with the history before the turn of the last century, and does so very well, which leaves me wanting a little more when Marciano gets in and through the 20th and start of the 21st century so quickly. Still, this is an interesting read and one that is written in a way that keeps the reader engaged. It has further stoked my interest in the subject and in some of the key figures involved in the various histories, which is about all one can ask of such a book. If you are into this kind of history, this is a solid book that is worth your time, regardless of how you measure that time.

Although I was interested in the topic, I put off reading this book at first because I thought it would be about political grandstanding and fighting over measurement system in the 1970s. This is NOT that at all.

In cleverly numbered chapters (I won't spoil it), Marciano delves into the whole history of measurement standardization efforts over the last two centuries. I had never really realized that the US customary measures and the French metric system both developed out of their respective revolutions around the same time. Just about all the Founding Fathers had their say about standardization, including Thomas Jefferson, who seems to be making an appearance in every history book I've read over the past year or so.

But Marciano doesn't just cover feet, meters, ounces and liters. He also explores efforts to standardize time, calendars, languages, spelling and monetary systems. In fact, I had never been aware just how closely currency was related to weights and measures. The author outlines this nicely. A cast of characters from history make appearances throughout the book, from John Quincy Adams to Napoleon, from George Eastman and Andrew Carnegie to my personal favorite, Melville Dewey. It's a pretty wild ride and Marciano keeps it interesting the whole way.

In the end, he seems content to admire the efforts on all sides of these issues, and points out that our two systems -- he describes the US as effectively being bimensural -- are now tightly intertwined, saying that "...the metric system can be our operating system without being our interface."

This paragraph from the last chapter sums things up nicely:

In cleverly numbered chapters (I won't spoil it), Marciano delves into the whole history of measurement standardization efforts over the last two centuries. I had never really realized that the US customary measures and the French metric system both developed out of their respective revolutions around the same time. Just about all the Founding Fathers had their say about standardization, including Thomas Jefferson, who seems to be making an appearance in every history book I've read over the past year or so.

But Marciano doesn't just cover feet, meters, ounces and liters. He also explores efforts to standardize time, calendars, languages, spelling and monetary systems. In fact, I had never been aware just how closely currency was related to weights and measures. The author outlines this nicely. A cast of characters from history make appearances throughout the book, from John Quincy Adams to Napoleon, from George Eastman and Andrew Carnegie to my personal favorite, Melville Dewey. It's a pretty wild ride and Marciano keeps it interesting the whole way.

In the end, he seems content to admire the efforts on all sides of these issues, and points out that our two systems -- he describes the US as effectively being bimensural -- are now tightly intertwined, saying that "...the metric system can be our operating system without being our interface."

This paragraph from the last chapter sums things up nicely:

In the Babylonian sixtieths, Roman twelfths, and medieval halves, quarters and eighths there is the logic and genius of countless generations of people coming to grasp with the world around them, the same way there is a logic and genius in the Enlightenment tenths, hundredths and thousandths of the metric system. What is good about the latter does not negate what is good about the former.

Dull writing doesn’t exactly help sell a pretty dull topic, and a meandering sprawl of a narrative really salts the sundae. I slogged my way through this thing while waiting for another book to come over the wire but can’t say I enjoyed it.

The title of the book is a little misleading as the USA's failure to fully adopt the metric system is only a small part in a wide-ranging story about the desire for some to come up with one unifying standard for everything in the world, including money and language.

The metric system was born out of the Enlightment and put into place during the French Revolution. France's new government loved a standard and rational way of measuring things. And they loved the decimal system. Everything for a while was decimalized, even a calendar that featured 10 day weeks.

Eventually, the system changed into what is used today. It took a while for it to catch on as even France went away from it during Napoleon's time. But, it eventually caught on again, except in two notable places: the United States and Great Britain.

The British weren't about to have a the French tell them just how to measure things. The UK didn't go fully metric until the 1990s when the European Union forced them to. (And they still don't like it.)

Americans never have embraced the metric system. As far back as 1817, John Quincy Adams wrote a report stating that the metric system was more or less a passing fad. There was a push to adopt in the 1970s, but it fell prey to the problem that most changes have in America, i.e., people just don't want to change and learn new things.

Marciano points out that not all parts of customary measures (as the system in the U.S. is referred to) are illogical. Having measurements that can be divided by 2 or 4 or 8 or 3 are very handy.

The idea of a 60-second minute, 60-minute hour, and 24-hour day has probably been the one measurement that the entire world has agreed upon. Even the U.S. and North Korea agree on that.

Will America ever go metric? It sort of already has, even though we still use miles and feet and pounds. Our aircraft use metric measurements. We got to the moon on the metric system. We like buying soda in 2 liter bottles. We read nutrition information to see how many grams of fat are in it.

Technology has made all types of measurement universal. It's all just a matter of doing the math.

The metric system was born out of the Enlightment and put into place during the French Revolution. France's new government loved a standard and rational way of measuring things. And they loved the decimal system. Everything for a while was decimalized, even a calendar that featured 10 day weeks.

Eventually, the system changed into what is used today. It took a while for it to catch on as even France went away from it during Napoleon's time. But, it eventually caught on again, except in two notable places: the United States and Great Britain.

The British weren't about to have a the French tell them just how to measure things. The UK didn't go fully metric until the 1990s when the European Union forced them to. (And they still don't like it.)

Americans never have embraced the metric system. As far back as 1817, John Quincy Adams wrote a report stating that the metric system was more or less a passing fad. There was a push to adopt in the 1970s, but it fell prey to the problem that most changes have in America, i.e., people just don't want to change and learn new things.

Marciano points out that not all parts of customary measures (as the system in the U.S. is referred to) are illogical. Having measurements that can be divided by 2 or 4 or 8 or 3 are very handy.

The idea of a 60-second minute, 60-minute hour, and 24-hour day has probably been the one measurement that the entire world has agreed upon. Even the U.S. and North Korea agree on that.

Will America ever go metric? It sort of already has, even though we still use miles and feet and pounds. Our aircraft use metric measurements. We got to the moon on the metric system. We like buying soda in 2 liter bottles. We read nutrition information to see how many grams of fat are in it.

Technology has made all types of measurement universal. It's all just a matter of doing the math.

My favorite bit was the bit about the world calendar, and how seriously that was taken.

#notgoodforthejews

#notgoodforthejews

Thin history of standardization, decimalization, and yes, metrification of the world. Many historical points were quite brief, but there was a lot to cover. One chapter on standardized spelling, two more solid chapters on the French revolution and their "interesting" calendar. Other calendar experiments are among the more interesting parts of the book.

In the penultimate chapter we get to the question of America and the failed 70s push for metric. Not as interesting as you would think - some baggage from the push in the 1870s, some political infighting. The final chapter summarizes the current state of affairs - a hodge-podge of units for the masses, metric for scientists, and only briefly touches on the Mars mission failure.

While interesting, it felt a lot more like an overview. The answer to the title question was unsatisfying - what we do today is okay, and computers can cover the rest. 2½ stars.

In the penultimate chapter we get to the question of America and the failed 70s push for metric. Not as interesting as you would think - some baggage from the push in the 1870s, some political infighting. The final chapter summarizes the current state of affairs - a hodge-podge of units for the masses, metric for scientists, and only briefly touches on the Mars mission failure.

While interesting, it felt a lot more like an overview. The answer to the title question was unsatisfying - what we do today is okay, and computers can cover the rest. 2½ stars.