You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

“Didn’t I love her enough? I knew I did - and put off half my future for her. Didn’t she love me enough? I knew she did - and gave up half her past for me.”

I like Julian Barnes but he is a TAD obsessed with Noah and his ark.

As I read this book, I tried to find the missing 1/2 chapter that's being mentioned in the title. The hints came along the way, as this book tries to portray itself as a footnote to history. It criticises the nature of history and how it's being written, "When inadequacy of the evidence are met with the interest of the writers". Most of the time, we don't read the truth in history. We only read what the historians try to show to us. And that's the problem with our world now, in this world when overflooded information appears in our lives.

adventurous

challenging

emotional

funny

hopeful

lighthearted

mysterious

reflective

relaxing

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

N/A

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

Shortly after starting this book, and even though I knew it was an early Barnes, I had to stop and check to see when it was written because it felt so immediate.

And what it tells me, with that Barnesian wry humor, is there’s not much hope:

(History just burps, and we taste again that raw-onion sandwich it swallowed centuries ago.) (From Parenthesis— the ½ chapter—, page 239, 76%)

There’s only this:

But we must still believe that objective truth is obtainable; or we must believe that it is 99 per cent obtainable; or if we can’t believe this we must believe that 43 per cent objective truth is better than 41 per cent. We must do so, because if we don’t we’re lost, we fall into beguiling relativity, we value one liar’s version as much as another liar’s, we throw up our hands at the puzzle of it all, we admit that the victor has the right not just to the spoils but also to the truth. (Also from Parenthesis, page 243, 78%)

And for some reason I find this idea appealing:

For the point is this: not that myth refers us back to some original event which has been fancifully transcribed as it passed through the collective memory; but that it refers us forward to something that will happen, that must happen. Myth will become reality, however sceptical we might be. (From the chapter Three Simple Stories, page 180, 57%)

And what it tells me, with that Barnesian wry humor, is there’s not much hope:

(History just burps, and we taste again that raw-onion sandwich it swallowed centuries ago.) (From Parenthesis— the ½ chapter—, page 239, 76%)

There’s only this:

But we must still believe that objective truth is obtainable; or we must believe that it is 99 per cent obtainable; or if we can’t believe this we must believe that 43 per cent objective truth is better than 41 per cent. We must do so, because if we don’t we’re lost, we fall into beguiling relativity, we value one liar’s version as much as another liar’s, we throw up our hands at the puzzle of it all, we admit that the victor has the right not just to the spoils but also to the truth. (Also from Parenthesis, page 243, 78%)

And for some reason I find this idea appealing:

For the point is this: not that myth refers us back to some original event which has been fancifully transcribed as it passed through the collective memory; but that it refers us forward to something that will happen, that must happen. Myth will become reality, however sceptical we might be. (From the chapter Three Simple Stories, page 180, 57%)

Apparently a loose collection of short stories, but the stories are all connected to each other. Not everything is immediately clear. Beautiful. Thematically, especially about the relationship science-faith, the supremacy of the people, the relationship people-animals. The Ark of Noah is the recurring storyline. Was my first acquaintance with Barnes, and surely not my last one!

adventurous

funny

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I’d buy the book if the whole thing was 10. The Dream and Parenthesis.

Barnes is a fantastic, incisive writer. Enjoyed this thoroughly (including the Dream, which has its real meat in the latter half. And then the book’s over.)

Definitely a book for people who can notice intertextual patterns, themes from short story to short story, motifs almost like pieces of an opera. Within, Barnes covers more than just history or Noah and his ark, it's about us as people surviving or not surviving catastrophe.

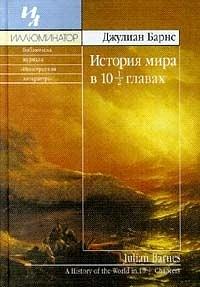

The notion of history as a steady procession of objective facts is, of course, absurd. In what is, essentially, a collection of short stories and essays linked by little more than a handful of recurring leitmotifs, Julian Barnes explores how history shapes and is shaped by every participant, and about the privilege of those who participate in and record our shared history.

Inevitably, some chapters work much better than others. The first chapter, the story of Noah’s ark told by a stowaway woodworm, is easily the standout, with the following chapter, being a fictionalisation of the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, unfortunately being the most pedestrian. This sums up the book, really. As intriguing and thought-provoking as the best chapters are, others feel a bit purposeless and meandering. The half chapter, an extended musing on the nature of love, felt particularly separate from everything else.

I would strongly recommend the first chapter but, for all its erudition and learning, I would not consider the rest of the book essential.

Inevitably, some chapters work much better than others. The first chapter, the story of Noah’s ark told by a stowaway woodworm, is easily the standout, with the following chapter, being a fictionalisation of the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, unfortunately being the most pedestrian. This sums up the book, really. As intriguing and thought-provoking as the best chapters are, others feel a bit purposeless and meandering. The half chapter, an extended musing on the nature of love, felt particularly separate from everything else.

I would strongly recommend the first chapter but, for all its erudition and learning, I would not consider the rest of the book essential.