Scan barcode

saareman's review

5.0

From Sound to Silence 1=(1+1)=1

Review of the Fordham University Press paperback edition (Dec. 2020)

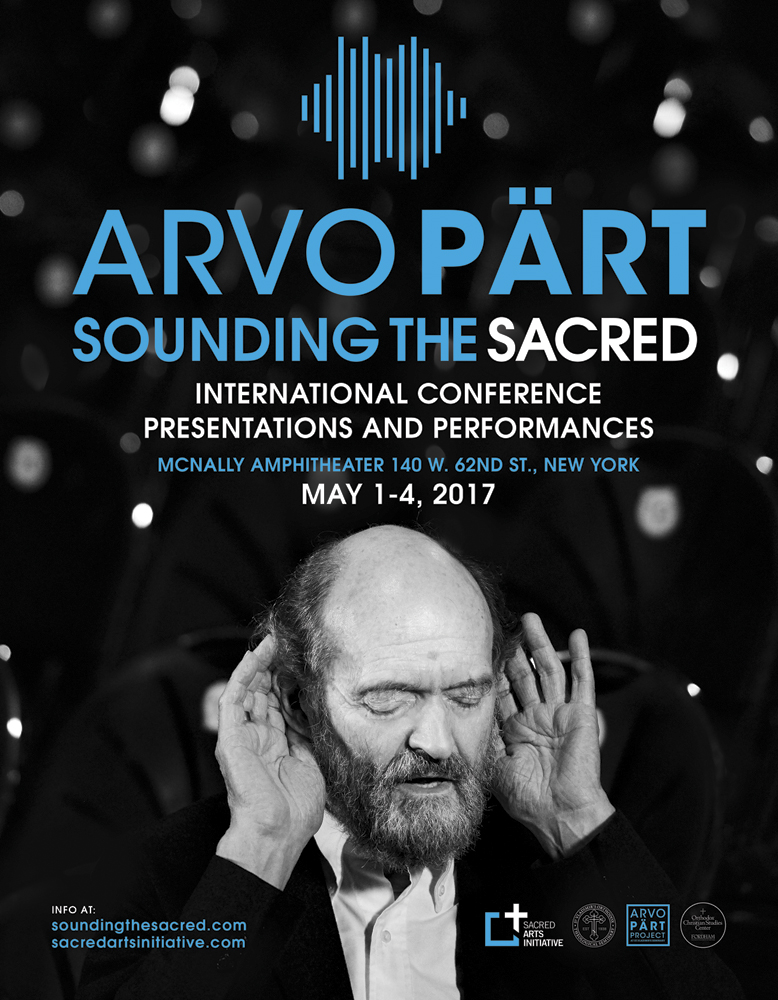

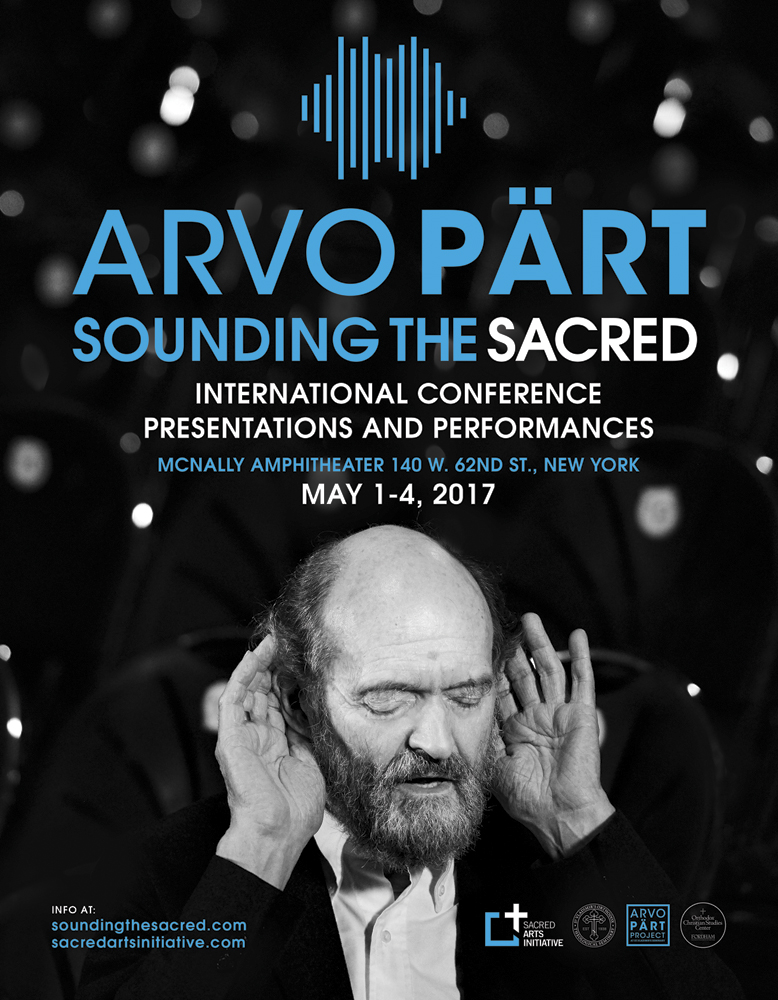

This collection of essays built around the works of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt grew out of the papers originally presented at the same-titled conference May 1-4, 2017 in New York City.

Conference poster sourced from the Arvo Pärt Centre.

The collection is especially well organized in themes with an Introduction followed by sections of History & Context, Performance, Materiality & Phenomenology, and Theology. Several of the essays are highly technical and do require knowledge of music theory and audiology to fully appreciate. To balance that there is a sufficient amount of basic history of the composer and his life and times for the non-technical reader. Although the conference was built around the theme of the sacred in the composer's works, the essays do not overly dwell on that aspect except for those in the Theology section.

I especially liked Sevin Yaraman's concluding essay In the Beginning There Was Sound: Hearing, Tintinnabuli and Musical Meaning in Sufism which expanded the Pärt universe into the realm of Sufism. The essay also extended Nora Pärt's famous equation which describes the effect of tintinnabuli that 1+1=1 (meaning that the Melody voice and the Tintinnabuli-voice sounding together are one sound and not two). Yaraman proposes the equation 1=(1+1)=1 to symbolize that from the one Source we are split into Two in this life until we return to the One in the end.

Highly recommended for deep Pärt scholars. For newcomers [b:The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt|14630476|The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt|Andrew Shenton|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1338224734l/14630476._SX50_.jpg|20275456] (2012) ed. Andrew Shenton is the ideal entry level work.

Trivia and Link

The book contains a teaser that Kevin C. Karnes, author of [b:Arvo Pärt's Tabula Rasa|35081903|Arvo Pärt's Tabula Rasa|Kevin C. Karnes|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1513341953l/35081903._SX50_.jpg|56382655] (2017) is working on an additional book which is [b:Sounds Beyond: Arvo Pärt and the 1970s Soviet Underground|57331835|Sounds Beyond Arvo Pärt and the 1970s Soviet Underground|Kevin C. Karnes|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1619878414l/57331835._SY75_.jpg|89724882] (expected publication November 19, 2021).

Review of the Fordham University Press paperback edition (Dec. 2020)

This collection of essays built around the works of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt grew out of the papers originally presented at the same-titled conference May 1-4, 2017 in New York City.

Conference poster sourced from the Arvo Pärt Centre.

The collection is especially well organized in themes with an Introduction followed by sections of History & Context, Performance, Materiality & Phenomenology, and Theology. Several of the essays are highly technical and do require knowledge of music theory and audiology to fully appreciate. To balance that there is a sufficient amount of basic history of the composer and his life and times for the non-technical reader. Although the conference was built around the theme of the sacred in the composer's works, the essays do not overly dwell on that aspect except for those in the Theology section.

I especially liked Sevin Yaraman's concluding essay In the Beginning There Was Sound: Hearing, Tintinnabuli and Musical Meaning in Sufism which expanded the Pärt universe into the realm of Sufism. The essay also extended Nora Pärt's famous equation which describes the effect of tintinnabuli that 1+1=1 (meaning that the Melody voice and the Tintinnabuli-voice sounding together are one sound and not two). Yaraman proposes the equation 1=(1+1)=1 to symbolize that from the one Source we are split into Two in this life until we return to the One in the end.

Highly recommended for deep Pärt scholars. For newcomers [b:The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt|14630476|The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt|Andrew Shenton|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1338224734l/14630476._SX50_.jpg|20275456] (2012) ed. Andrew Shenton is the ideal entry level work.

Trivia and Link

The book contains a teaser that Kevin C. Karnes, author of [b:Arvo Pärt's Tabula Rasa|35081903|Arvo Pärt's Tabula Rasa|Kevin C. Karnes|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1513341953l/35081903._SX50_.jpg|56382655] (2017) is working on an additional book which is [b:Sounds Beyond: Arvo Pärt and the 1970s Soviet Underground|57331835|Sounds Beyond Arvo Pärt and the 1970s Soviet Underground|Kevin C. Karnes|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1619878414l/57331835._SY75_.jpg|89724882] (expected publication November 19, 2021).

christopherc's review

3.0

The editors of this collection of papers claim that one of their goals is to apply “sound studies” to Pärt’s work. How that might actually differ from the number of other collections where musicologists analyze Pärt’s work is unclear, but the result is unfortunately that many of the contributions here feel rather lightweight.

A few papers are valuable: Christopher J. May’s on how Pärt’s film music of the 1970s – even though the composer downplays it as mere work-for-hire and strongly discourages research in it – actually has some striking connections to his early tintinnabuli output; Kevin C. Karnes’ on how some of the first tintinnabuli works were played in a Riga “underground” venue where Pärt was part of a small community of experimentalists; and Peter Bouteneff’s interview with Paul Hillier where the latter describes sonic details that must be paid attention to when performing Pärt’s music. An amusing succession of papers is first Andrew Shenton’s that propounds on the value of pure silence in Pärt’s music, and then then Jeffers Engelhardt’s that shows that actually in a resonant venue this isn’t silence at all and Pärt’s music is worth examinating from a spectralist perspective.

Other papers are almost stereotypes of unsatisfying academic writing. Alexander Lingas is really keen on comparing Pärt to the 14th-century English mystic Richard Rolle, but in spite of the writer’s great interest in the latter, the comparison isn’t very illuminating. Sevin Huriye Yaraman’s contribution on Pärt’s music from the perspective of Sufism is frankly offensive, considering how Pärt’s life and work is grounded in the Orthodox Christian faith.

A few papers are valuable: Christopher J. May’s on how Pärt’s film music of the 1970s – even though the composer downplays it as mere work-for-hire and strongly discourages research in it – actually has some striking connections to his early tintinnabuli output; Kevin C. Karnes’ on how some of the first tintinnabuli works were played in a Riga “underground” venue where Pärt was part of a small community of experimentalists; and Peter Bouteneff’s interview with Paul Hillier where the latter describes sonic details that must be paid attention to when performing Pärt’s music. An amusing succession of papers is first Andrew Shenton’s that propounds on the value of pure silence in Pärt’s music, and then then Jeffers Engelhardt’s that shows that actually in a resonant venue this isn’t silence at all and Pärt’s music is worth examinating from a spectralist perspective.

Other papers are almost stereotypes of unsatisfying academic writing. Alexander Lingas is really keen on comparing Pärt to the 14th-century English mystic Richard Rolle, but in spite of the writer’s great interest in the latter, the comparison isn’t very illuminating. Sevin Huriye Yaraman’s contribution on Pärt’s music from the perspective of Sufism is frankly offensive, considering how Pärt’s life and work is grounded in the Orthodox Christian faith.