Take a photo of a barcode or cover

dark

emotional

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

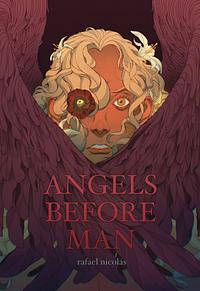

There is a peculiar cruelty in retellings: you carry the ending like a lodged coin in your mouth and every taste of sweetness turns metallic. Nicolás knows this and uses it. He takes the ancient scaffold of the Fall and strings chandeliers of gold, pearls, moons, citrus and coals from it; he lays down a carpet of syntax so lush it makes you dizzy—and then, with a surgeon’s glee, he begins to cut.

Part I reads like sunlight on glass: dazzling, precise, and refracting into a thousand private colours. The beginning is uncanny in its tenderness. Creation is tactile here—hands that sew and sculpt, suns placed into sockets like marbles, hips braided from tides, hair woven from stars—and yet every act of crafting hums with small, inevitable violence.

Part I reads like sunlight on glass: dazzling, precise, and refracting into a thousand private colours. The beginning is uncanny in its tenderness. Creation is tactile here—hands that sew and sculpt, suns placed into sockets like marbles, hips braided from tides, hair woven from stars—and yet every act of crafting hums with small, inevitable violence.

“He opened you like a citrus and planted a garden of budding flowers inside.”

That simile is a promise and a threat at once. It says: behold beauty; and it says also: behold what beauty costs.

Nicolás’s greatest achievement is not his imagery (though the imagery is cunning and incandescent) but his ethical reimagining: love as a mechanism of erasure. Love becomes hunger. Worship becomes compulsion. Faith—so often the salve of myth—is here weaponized against itself. This is the book’s cold, brilliant pivot: the divine touch that should be cradle becomes the hand that tills a wound. The theological paradox the novel tracks—whether God is good because He is good, or because He says He is good—is not idle speculation but a moral detonator. It explodes.

The prose is a fever: sentences that flower into entire frescoes, then snap into fragments; points of view that slide like quicksilver, sometimes staying in the third person, then slipping into intimate first for a heartbeat as if you were eavesdropping on a confession. The voice can be both sublime and breathless, occasionally too indulgent for its own good. The luxuriance works—until it does not. Phrases break off mid-flight; a sentence will open like a gate and then, bewilderingly, slam. The result: there are moments where the lyrical rush lifts you, and moments where it pushes you away. The astringency of that push is not always welcome. It distracts, at times, from the scene it means to illumine.

But oh, when it lands. When it lands it pierces. The relationship between Lucifer and Michael is a masterclass in tragic ambivalence.

Nicolás’s greatest achievement is not his imagery (though the imagery is cunning and incandescent) but his ethical reimagining: love as a mechanism of erasure. Love becomes hunger. Worship becomes compulsion. Faith—so often the salve of myth—is here weaponized against itself. This is the book’s cold, brilliant pivot: the divine touch that should be cradle becomes the hand that tills a wound. The theological paradox the novel tracks—whether God is good because He is good, or because He says He is good—is not idle speculation but a moral detonator. It explodes.

The prose is a fever: sentences that flower into entire frescoes, then snap into fragments; points of view that slide like quicksilver, sometimes staying in the third person, then slipping into intimate first for a heartbeat as if you were eavesdropping on a confession. The voice can be both sublime and breathless, occasionally too indulgent for its own good. The luxuriance works—until it does not. Phrases break off mid-flight; a sentence will open like a gate and then, bewilderingly, slam. The result: there are moments where the lyrical rush lifts you, and moments where it pushes you away. The astringency of that push is not always welcome. It distracts, at times, from the scene it means to illumine.

But oh, when it lands. When it lands it pierces. The relationship between Lucifer and Michael is a masterclass in tragic ambivalence.

“You’re everything to me, the stars and the moons, the heat and the cold, the earth and the seeds, the waters and the flowers, but you are not God.”

Michael’s love is both sanctuary and indictment. It offers solace, tenderness, the sweetness of being seen entirely—and yet it comes barbed, bound by obedience to a higher order. His embrace is safety, but it is also a cage; his tenderness affirms Lucifer’s worth, while simultaneously denying him the right to exist outside of God’s shadow. To be loved by Michael is to be cherished, yes, but also to be constantly measured against a divine scale where love itself becomes conditional. The very act of his devotion reassures and condemns in the same breath, making his love a place of refuge that is inseparable from betrayal.

And Lucifer—what a portrait. A creature braided from marble and pearl and tidal hips, and yet hollow, asking: “What is inside me?” He asks not in metaphysical curiosity but in existential terror. To be made of beauty without being allowed to be a self; to be mirrored always and never to look straight into one’s own eye; to equate love with annihilation. Nicolás gives us a Lucifer who is not merely proud, not merely ambitious, but unbearably human: dependent, hungry, frightened of being the “favorite,” terrified of the solitude that accompanies singular adoration. His rebellion reads less like pure arrogance and more like a last, terrible attempt at personhood.

Angels Before Man interrogates worship, possession, and the ontology of being-made. It turns Eden on its head: paradise is interrogated as a behemoth of habitation for the powerful, not a refuge for the cherished. “Paradise for who?” the text asks. For God, perhaps. For whom else? The answer is the wound. The book’s moral center is cruel: the most damning sin Lucifer commits is not pride in the vulgar sense but the sin of seeking to be loved in his own name. To be loved becomes, perversely, the crime.

Part I is intoxicating and finished me in one sit. And there I paused. I stopped at the seam because the architecture of the novel has been constructed to make the reader dread what follows, to let that dread ferment like a bitter wine in the throat. That hesitation is not a failing in me, but a testament to Nicolás’s craft: he has made the prelude unbearable precisely so the fall will land as ruin. I feared Part II. I feared its inevitable unmaking. I was not wrong to fear.

In the end, the book’s grandeur is also its ache. It is a tragic hymn to the cost of selfhood in a heaven that demands one’s whole attention. It is a retelling that understands that the old myth’s moral—pride as the original sin—is insufficient without the recognition that pride is often a final, bloody answer to erasure. Angels Before Man does not simply retell; it re-reads the wound and turns the reader’s gaze to the scar.

Read it if you want to be unmade and then remade by language. Read it if you are not afraid of being held up to a mirror by a writer who loves beauty so fiercely he will carve it open to see what bleeds inside. But be warned: happiness in this book is a tremor of light before the plunge. You will savor it. Then you will feel sick. And then—perhaps—you will understand why the fall could not be anything else.

And Lucifer—what a portrait. A creature braided from marble and pearl and tidal hips, and yet hollow, asking: “What is inside me?” He asks not in metaphysical curiosity but in existential terror. To be made of beauty without being allowed to be a self; to be mirrored always and never to look straight into one’s own eye; to equate love with annihilation. Nicolás gives us a Lucifer who is not merely proud, not merely ambitious, but unbearably human: dependent, hungry, frightened of being the “favorite,” terrified of the solitude that accompanies singular adoration. His rebellion reads less like pure arrogance and more like a last, terrible attempt at personhood.

Angels Before Man interrogates worship, possession, and the ontology of being-made. It turns Eden on its head: paradise is interrogated as a behemoth of habitation for the powerful, not a refuge for the cherished. “Paradise for who?” the text asks. For God, perhaps. For whom else? The answer is the wound. The book’s moral center is cruel: the most damning sin Lucifer commits is not pride in the vulgar sense but the sin of seeking to be loved in his own name. To be loved becomes, perversely, the crime.

Part I is intoxicating and finished me in one sit. And there I paused. I stopped at the seam because the architecture of the novel has been constructed to make the reader dread what follows, to let that dread ferment like a bitter wine in the throat. That hesitation is not a failing in me, but a testament to Nicolás’s craft: he has made the prelude unbearable precisely so the fall will land as ruin. I feared Part II. I feared its inevitable unmaking. I was not wrong to fear.

In the end, the book’s grandeur is also its ache. It is a tragic hymn to the cost of selfhood in a heaven that demands one’s whole attention. It is a retelling that understands that the old myth’s moral—pride as the original sin—is insufficient without the recognition that pride is often a final, bloody answer to erasure. Angels Before Man does not simply retell; it re-reads the wound and turns the reader’s gaze to the scar.

Read it if you want to be unmade and then remade by language. Read it if you are not afraid of being held up to a mirror by a writer who loves beauty so fiercely he will carve it open to see what bleeds inside. But be warned: happiness in this book is a tremor of light before the plunge. You will savor it. Then you will feel sick. And then—perhaps—you will understand why the fall could not be anything else.

Graphic: Body horror, Gore, Violence

Moderate: Rape, Self harm, Sexual content, Cannibalism

Minor: Animal cruelty

dark

emotional

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Complicated

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

Just wasn't for me. It was written in a very interesting yet strange way but mostly the story wasn't my kind of thing.

Lucifer was a cutie though and I'm sure he goes on to have a wonderful life in Heaven where God lets him be and doesn't interfere with anything.

Lucifer was a cutie though and I'm sure he goes on to have a wonderful life in Heaven where God lets him be and doesn't interfere with anything.

dark

emotional

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

Utterly heartbreaking. And so beautiful.

Graphic: Gore, Torture, Violence, Abandonment

Moderate: Sexual content

Minor: Sexual assault, Sexual violence

adventurous

challenging

emotional

funny

mysterious

tense

medium-paced

Rafael Nicolás has to pay my therapy bills after this

dark

emotional

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Complicated

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

dark

emotional

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

dark

emotional

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

emotional

mysterious

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes