Take a photo of a barcode or cover

challenging

dark

funny

mysterious

reflective

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

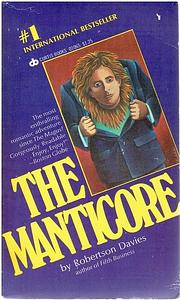

This short novel, the second in a series that brings Canadian magical realism* to the literary stage, is jam-packed with axioms and truism that I want to paint onto my walls.

David Staunton is one who could be called an unreliable unreliable narrator, but then we recall that he is also learning about himself, and that if he is unreliable it may not be entirely his fault. Right from the start, his contradictory remarks about women make you laugh out loud. I don't know that it's supposed to be, but honestly, I felt that Staunton (or, Davies) gave us a humorous narrative of philosophical axioms.

"People very often dream of things they don't know... it is because great myths are not invented stories but objectivizations of images and situations that lie very deep in the human spirit; a poet may make a great embodiment of a myth, but it is the mass of humanity that knows the myth to be a spiritual truth, and that is why they cherish his poem" (p. 147)

One of the delicious gems was a quote from Ibsen: "To live is to battle with trolls/ in the vaults of heart and brain./ To write: that is to sit/ in judgment over one's self" (p. 60, p. 192)

David, early into his psychotherapy: "If love is to be watched and listened to without embarrassment, it must be transmuted into art" (p. 132)

David recalls someone quoting, "The law, besides being a profession, is one of the humanities" (p. 190)

"Every man who amounts to a damn has several father's, and the man who begat him in list or drink of for a bet or even in the sweetness of honest love may not be the most important father. The fathers you choose for yourself are the significant ones. But you didn't choose Boy, and you never knew him. No; no man knows his father. If Hamlet had known his father he would never have made such an almighty fuss about a man who was fool enough to marry Gertrude" (p. 244)

"I suppose unless you are unlucky, anywhere you spend your summers as a child is an Arcadia forever" (p. 67)

Fun Fact:

Five-board chess "to think both horizontally and laterally at the same time" (p.234)

*The magical realism apparently comes in Book 3, but there was something about going into the literal cave, followed by the open-ended conclusion, that makes me think Davies is setting the stage from Book 2.

David Staunton is one who could be called an unreliable unreliable narrator, but then we recall that he is also learning about himself, and that if he is unreliable it may not be entirely his fault. Right from the start, his contradictory remarks about women make you laugh out loud. I don't know that it's supposed to be, but honestly, I felt that Staunton (or, Davies) gave us a humorous narrative of philosophical axioms.

"People very often dream of things they don't know... it is because great myths are not invented stories but objectivizations of images and situations that lie very deep in the human spirit; a poet may make a great embodiment of a myth, but it is the mass of humanity that knows the myth to be a spiritual truth, and that is why they cherish his poem" (p. 147)

One of the delicious gems was a quote from Ibsen: "To live is to battle with trolls/ in the vaults of heart and brain./ To write: that is to sit/ in judgment over one's self" (p. 60, p. 192)

David, early into his psychotherapy: "If love is to be watched and listened to without embarrassment, it must be transmuted into art" (p. 132)

David recalls someone quoting, "The law, besides being a profession, is one of the humanities" (p. 190)

"Every man who amounts to a damn has several father's, and the man who begat him in list or drink of for a bet or even in the sweetness of honest love may not be the most important father. The fathers you choose for yourself are the significant ones. But you didn't choose Boy, and you never knew him. No; no man knows his father. If Hamlet had known his father he would never have made such an almighty fuss about a man who was fool enough to marry Gertrude" (p. 244)

"I suppose unless you are unlucky, anywhere you spend your summers as a child is an Arcadia forever" (p. 67)

Fun Fact:

Five-board chess "to think both horizontally and laterally at the same time" (p.234)

*The magical realism apparently comes in Book 3, but there was something about going into the literal cave, followed by the open-ended conclusion, that makes me think Davies is setting the stage from Book 2.

Me: You simply HAVE to read "The Manticore", by Robertson Davies.

Customer: What's it about?

Me: Well it's about this insufferable middle-aged lawyer who drinks to forget his fabulously wealthy upbringing. He is so unhappy he decides to undergo Jungian analysis in Switzerland for a year or so. The story is told via entries from his therapeutic journal.

Customer: I'll take eight!

I have decided that describing the premise of a Robertson Davies novel is pointless. That is unless, you want to deter someone from ever reading one of his books.

Therefore I won't even bother explaining what happens in this book. It's not about the external/concrete events with Davies--it's what his characters take away from the events.

Besides, this is the second book in a trilogy, so if you have read Fifth Business already, and are considering reading the second one, you'll already 'get' what makes these books so great.

As for the people complaining about how annoying David is at first, I have to say that they are missing the point of the entire book. He is reckoning with his whole personality, good and bad, and he begins at a very unhealthy place. Cut him some slack. It wouldn't be very interesting if he was totally fine when the book began and just stayed fine the rest of the novel.

I would recommend this book to anyone who liked Fifth Business, and especially to those who are somewhat familiar with Carl Jung.

Customer: What's it about?

Me: Well it's about this insufferable middle-aged lawyer who drinks to forget his fabulously wealthy upbringing. He is so unhappy he decides to undergo Jungian analysis in Switzerland for a year or so. The story is told via entries from his therapeutic journal.

Customer: I'll take eight!

I have decided that describing the premise of a Robertson Davies novel is pointless. That is unless, you want to deter someone from ever reading one of his books.

Therefore I won't even bother explaining what happens in this book. It's not about the external/concrete events with Davies--it's what his characters take away from the events.

Besides, this is the second book in a trilogy, so if you have read Fifth Business already, and are considering reading the second one, you'll already 'get' what makes these books so great.

As for the people complaining about how annoying David is at first, I have to say that they are missing the point of the entire book. He is reckoning with his whole personality, good and bad, and he begins at a very unhealthy place. Cut him some slack. It wouldn't be very interesting if he was totally fine when the book began and just stayed fine the rest of the novel.

I would recommend this book to anyone who liked Fifth Business, and especially to those who are somewhat familiar with Carl Jung.

I struggled with this one, and I still do. Davies is a masterful writer, but the premise and the story that unfolds from it are both quite strange stuff—strange in a sense that made me fight the book instead of surrendering to it. Much of it is phrased as a patient's session with a psychoanalyst, and Davies doesn't make this more interesting than it usually is: half the time is spent debating the merits of the analysis itself, dreams are dissected, the patient falls in love with the doctor, and so on. There are great little moments here, but I guess the chief thing I'm feeling right now is that I'd still gladly recommend the precursor, 'Fifth Business', to anyone, and I wouldn't rush to recommend 'The Manticore'.

This book was so incredible. The story is captivating. I found myself not realizing that hours had past while I had been reading.

Après le succès de Fifth Business, Davies écrivit The Manticore (1972), (traduit en français deux fois : une fois sous le titre Le lion avait un visage d'homme; et une fois sous le titre Le manticore), un roman qui raconte en plus de détail la psychologie analytique de Jung. Ce roman valut à Davies le Prix du Gouverneur général. Vint ensuite World of Wonders (1975) (traduit en français sous le titre Le monde des merveilles). Plus tard, on baptisa ces trois romans la Trilogie de Deptford.

The Foreigners We Deserve

A remarkable journey of Jungian psychoanalysis. Manticore will therefore appeal to Platonists (as myself) who recognise the limits of language but also its necessity in figuring out what we are. Aristotelian scientific types are likely to be disappointed. Freud thought in terms of flaws in the psyche brought about through trauma, Jung in terms of psychic purpose and its adaptations. There is no rational way to choose between the two perspectives; the facts fit either. Aesthetically, however, Jung takes the upper hand; and Davies knows why: human beings are remarkably elegant creatures even at their least attractive. Understanding this basic principle makes life interesting as well as bearable. We are all full of foreigners, alien psychic beings, vying for attention and supremacy. The more we reject their presence, the more power they exert. A possible lesson here for Trump in his policy formulation as well as in his personal life?

A remarkable journey of Jungian psychoanalysis. Manticore will therefore appeal to Platonists (as myself) who recognise the limits of language but also its necessity in figuring out what we are. Aristotelian scientific types are likely to be disappointed. Freud thought in terms of flaws in the psyche brought about through trauma, Jung in terms of psychic purpose and its adaptations. There is no rational way to choose between the two perspectives; the facts fit either. Aesthetically, however, Jung takes the upper hand; and Davies knows why: human beings are remarkably elegant creatures even at their least attractive. Understanding this basic principle makes life interesting as well as bearable. We are all full of foreigners, alien psychic beings, vying for attention and supremacy. The more we reject their presence, the more power they exert. A possible lesson here for Trump in his policy formulation as well as in his personal life?

Definitely not as good as Fifth Business. David Staunton is an utterly dislikeable character who I did not relate to in the slightest. But Robertson Davies' beautiful writing had me hanging on to what was really a very poignant and deep character study. Though it would have been better if we could have delved into someone with a bit more charm.

emotional

mysterious

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

challenging

emotional

mysterious

reflective

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

A fine read. Ended well, looking forward to see the direction of the final book of the trilogy.