Take a photo of a barcode or cover

adventurous

dark

mysterious

sad

tense

medium-paced

2025 will be one-word reviews and a short explanation of the word-choice:

"Vicious"

Werewolves living among us. Can they? Can a family of werewolves survive themselves? Can a boy choose to be a boy, or must he become the wolf?

"Vicious"

Werewolves living among us. Can they? Can a family of werewolves survive themselves? Can a boy choose to be a boy, or must he become the wolf?

adventurous

emotional

funny

lighthearted

mysterious

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

challenging

dark

emotional

hopeful

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

adventurous

challenging

dark

emotional

mysterious

reflective

sad

tense

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

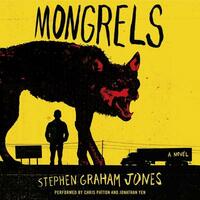

I’ve not read anything by Stephen Graham Jones before, but his name has been coming up pretty regularly, as an Indigenous author and horror author who’s apparently been putting out some bangers lately. I was on the hunt for an audiobook to listen to while snowed in, and while searching for werewolf books, his 2016 novel Mongrels popped up. I’d never heard of Mongrels, but as a certified Fan of Werewolves who’d been meaning to check out something by Jones anyway, it was pretty win/win.

Mongrels is about an unnamed boy in a family of werewolves, born to a single mother who died in childbirth and raised by his grandfather, Aunt Libby, and Uncle Darren. When his grandfather passes away, the three remaining family members live a nomadic life, traveling across much of the American South on the hunt for a place where his aunt and uncle can find work and maybe live for a few months without too much hassle. The novel is mostly told through first-person vignettes, with each chapter working fairly well as a standalone short story about the same characters, interspersed with much shorter, usually more humorous, stories told in third person. As the protagonist grows up, he learns more and more about life as a werewolf, the many measures his aunt and uncle take to work around difficulties with the transformation process and werewolf social norms. Despite this, he keeps missing every opportunity to transform, until he’s well past the age at which he could even be considered a late bloomer.

Werewolves are a useful metaphor for disability and queerness, but here, they instead work as a metaphor for poverty or being undocumented, or life on the fringes more broadly. It makes sense and comes from a similar place - the werewolf metaphor is strongest to me when it’s about those times when being true to oneself or living authentically means that society more broadly views you as without dignity, or less than human. That’s why so many lesser werewolf stories lean into lurid shock value over sexual assault and other acts that actually do justifiably cause society to judge the people who do them. I guess that’s what happens when people who don’t experience - and can’t imagine - marginalization try to write a book about being marginalized.

Mongrels is refreshingly free of lurid objectification or sexualization, which is honestly a bit of a miracle for werewolf fiction. Instead, the protagonist is a child who’s mostly getting the descriptions of what it is like to be a werewolf second-hand. The book doesn’t have a power fantasy at its center because its protagonist doesn’t experience any of the power. He just has to live the life stripped of continuity and deal with the repercussions of his aunt and uncle’s actions as wolves without getting to run free in the woods or hunt for deer or scare the people who threaten him. Throughout, it led me to ask: is it useful that he’s learning so much about the werewolf life? He wants to drop out of school like his aunt and uncle because school isn’t useful for werewolves. But…like…it is useful for humans who don’t turn into wolves, and he’s increasingly looking like maybe he’s not a wolf.

That’s kinda the question at the heart of the novel. What will this kid’s life look like if he turns out not to be a werewolf? He starts most chapters with a fact about “us wolves,” but then often undercuts it by acknowledging that what he just said doesn’t actually apply to him yet - but it will, as soon as he changes for the first time! This leads me to wonder if that’s partly the point. Many of the facts about werewolves aren’t really werewolf things so much as they are things a family resorts to when they’re barely subsisting on the margins of society, like getting what education you can from watching game shows or knowing how to shoplift food. Just as the protagonist is learning life skills that won’t necessarily be useful in life, marginalized families often are forced to impart to their children survival methods that won’t carry over if they manage to claw their way out of the margins. It’s setting them up for failure, in a way, but out of necessity. As the protagonist points out at one point, werewolves can’t afford to think about the past or the future - the only thing that can matter is right now.

I really enjoyed Mongrels, but it took me a little time to sink into it. I think I was expecting something a lot more violent or disturbing, and the book’s relative calm ironically caught me off-guard. To my mind, it’s not really a horror novel. There’s a little gore here and there, but never in a way that seemed purposely unsettling. It’s primarily a funny and bittersweet coming-of-age story about a boy whose aunt and uncle are doing the best they can to raise him (though really his aunt’s best is better than his uncle’s). But, you know, with werewolves.

Mongrels is about an unnamed boy in a family of werewolves, born to a single mother who died in childbirth and raised by his grandfather, Aunt Libby, and Uncle Darren. When his grandfather passes away, the three remaining family members live a nomadic life, traveling across much of the American South on the hunt for a place where his aunt and uncle can find work and maybe live for a few months without too much hassle. The novel is mostly told through first-person vignettes, with each chapter working fairly well as a standalone short story about the same characters, interspersed with much shorter, usually more humorous, stories told in third person. As the protagonist grows up, he learns more and more about life as a werewolf, the many measures his aunt and uncle take to work around difficulties with the transformation process and werewolf social norms. Despite this, he keeps missing every opportunity to transform, until he’s well past the age at which he could even be considered a late bloomer.

Werewolves are a useful metaphor for disability and queerness, but here, they instead work as a metaphor for poverty or being undocumented, or life on the fringes more broadly. It makes sense and comes from a similar place - the werewolf metaphor is strongest to me when it’s about those times when being true to oneself or living authentically means that society more broadly views you as without dignity, or less than human. That’s why so many lesser werewolf stories lean into lurid shock value over sexual assault and other acts that actually do justifiably cause society to judge the people who do them. I guess that’s what happens when people who don’t experience - and can’t imagine - marginalization try to write a book about being marginalized.

Mongrels is refreshingly free of lurid objectification or sexualization, which is honestly a bit of a miracle for werewolf fiction. Instead, the protagonist is a child who’s mostly getting the descriptions of what it is like to be a werewolf second-hand. The book doesn’t have a power fantasy at its center because its protagonist doesn’t experience any of the power. He just has to live the life stripped of continuity and deal with the repercussions of his aunt and uncle’s actions as wolves without getting to run free in the woods or hunt for deer or scare the people who threaten him. Throughout, it led me to ask: is it useful that he’s learning so much about the werewolf life? He wants to drop out of school like his aunt and uncle because school isn’t useful for werewolves. But…like…it is useful for humans who don’t turn into wolves, and he’s increasingly looking like maybe he’s not a wolf.

That’s kinda the question at the heart of the novel. What will this kid’s life look like if he turns out not to be a werewolf? He starts most chapters with a fact about “us wolves,” but then often undercuts it by acknowledging that what he just said doesn’t actually apply to him yet - but it will, as soon as he changes for the first time! This leads me to wonder if that’s partly the point. Many of the facts about werewolves aren’t really werewolf things so much as they are things a family resorts to when they’re barely subsisting on the margins of society, like getting what education you can from watching game shows or knowing how to shoplift food. Just as the protagonist is learning life skills that won’t necessarily be useful in life, marginalized families often are forced to impart to their children survival methods that won’t carry over if they manage to claw their way out of the margins. It’s setting them up for failure, in a way, but out of necessity. As the protagonist points out at one point, werewolves can’t afford to think about the past or the future - the only thing that can matter is right now.

I really enjoyed Mongrels, but it took me a little time to sink into it. I think I was expecting something a lot more violent or disturbing, and the book’s relative calm ironically caught me off-guard. To my mind, it’s not really a horror novel. There’s a little gore here and there, but never in a way that seemed purposely unsettling. It’s primarily a funny and bittersweet coming-of-age story about a boy whose aunt and uncle are doing the best they can to raise him (though really his aunt’s best is better than his uncle’s). But, you know, with werewolves.

challenging

dark

reflective

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

"This is the way werewolf stories go. Never any proof. Just a story that keeps changing, like it's twisting back on itself, biting its own stomach to chew the poison out."

I finished this book on Friday, May 13, early in the morning, after staying up late to read to the end. What can I say, it's the type of book that demands to be read under the moon.

It's a pleasure to sink into genre fiction, and I believe it when they say Stephen Graham Jones is a master of modern horror. This book balances between a good old fashioned portrait of a monster, while also telling the coming-of-age story of a scrappy protagonist you can't help but root for. I also think this book provides a compelling allegory for what it means to be outcast in America, lending it more heft than your typical werewolf fantasy tale.

One of my favorite things that Jones does is introducing a perfectly innocuous detail and then excavating the chilling story behind it. For example, this book explains why it's dangerous when werewolves eat French fries (hint: it's not dangerous for the wolf). You also find out what it means for the protagonist's history that dogs don't go near his grandfather's house. Each of these details is a thread in a larger part of the story, weaving together seemingly episodic chapters and building to an ultimately satisfying conclusion.

This book never breaks character as an almost pulpy paperback, and yet I couldn't help but find endless parallels with particular American experiences — poverty in this country, or being undocumented, or being a fugitive, or being dispossessed of land and identity — any number of conditions manufactured by our modern world that push people to the very edges of society, living off desperation alone. For our protagonist and his aunt Libby and uncle Darren, "going wolf" is one of the reasons they don't fit, but it's also a fantasy escape, a way they're able to survive in an unforgiving landscape.

In the story, this family is constantly on the move, trying to get by on patchy low-income work, limited schooling, and scavenging for food. They can't manage certain aspects of their wolfy condition — existential dangers associated with having children, or dealing with silver poisoning. You find out later in the novel that there are ways to deal with these problems. Our characters, however, were cut off from this information. What Grandpa, Darren, and Libby do know about being a wolf is passed down carefully to the protagonist, with the urgency of imparting an education essential to survival.

I'm reading [b:An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States|57570731|An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States|Kyle T. Mays|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1617719403l/57570731._SY75_.jpg|90160083] by Kyle T. Mays at the moment, and Mays talks about loss of land as more than just not having a physical place to put down roots and call your own. It's also a forceful deprivation of space in which meaning and identity is made, preserved, and passed down. The experiences of the characters in this book feel very uprooted, very cut off from cultural knowledge and memory — something all too common among Indigenous people in modern day nations shaped by imperialism. I don't think this reading is too far off, given that Jones is a member of the Blackfeet Tribe, and writes explicitly about Indigenous experiences in his other novels.

The lack of access to werewolf reproductive healthcare is also hitting close to home at the moment — or at least, the pain these characters feel at not being able to rely on any kind of safety or certainty when it comes to having children is hitting close to home. The protagonist is haunted by his mother's death during childbirth (wolf birth?), and Darren swears not to form any kind of long-term attachment; the risk of having children isn't worth it.

There are many other parallels that can be found, and many ways to read the story. This book, in the words of David Bowie, "dares you to care for the people on the edge of the night."

Next, I'll be reading [b:My Heart Is a Chainsaw|55711617|My Heart Is a Chainsaw (The Lake Witch Trilogy, #1)|Stephen Graham Jones|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1623264202l/55711617._SY75_.jpg|86884065] by Jones. It's his take on the slasher genre, and I found it in one of those little box libraries on a walk the other day. It felt like a great coincidence after just finishing Mongrels. Going by the first chapter, though, I'm going to be 100 times more creeped out by that book. Unlike Mongrels, Chainsaw might be one I confine to reading only by the light of day.

dark

emotional

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

adventurous

dark

emotional

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

adventurous

dark

emotional

funny

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes