Take a photo of a barcode or cover

challenging

informative

medium-paced

informative

medium-paced

“Cancellation is not criticism; cancellation is the absence of criticism. It is the replacement of criticism with a summary punishment”

The quote above is attributed to a recent Atlantic article (https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/cancellation-unc-nikole-hannah-jones/618951/) regarding the denied tenure ship of Nikole Hannah-Jones. The denial’s reasons have not been released, but due to Hannah-Jones political work on the 1619 project, one has to consider if her politics misalignment to her university was the cause for the dismissal.

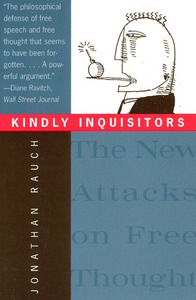

Authority and the scientific method seem to be the primary discussion points of Rauch’s work. Rauch makes the distinction between fact and opinion. Facts being replicable by persons, regardless of their identification with a marginalization or special interest group. Standing on the axiomatic principal of Popper’s falsifiability law, that science can only disprove, the implication is that science’s growth is largely from abandoning theory and perspectives that melt under scrutiny.

Bertrand Russell once wrote “order without authority” may well be the liberal science (p.57). Rauch attempts to couch arguments within the arguments of epistemology. Plato’s educational goal to inoculate the citizens with virtue and belief sounds reasonable. But with central authority comes the risk that continues into our time. Some beliefs may not be respected. Some may not even be allowed. Rauch’s work continues in the great liberal tradition of espousing an unshackled trust in freedom of speech and expression.

Examples of campus speaker cancellations, fatwas against apostates and continual distrust of freedom are from the 90s and early 2000’s, but the threat to freedom of speech from authorities is ever present. The political spectrum abounds with authorities who will not tolerate speech that insensitive, hurtful or biased. From totalitarian/despotic governments (Saudia Arabia, the People’s Republic of China) to the Marxist underpinnings of social theory (woke culture). Speaking harmfully is punishable. Social media’s value of rightness over truthfulness may be the most visible example of the liberal/humanitarian divide.

Judith Skhlar, a modern philosopher, states that what we value most is “not to harm”. And so with our societies growing connectedness, the everyday actions of all of us are increasingly under scrutiny. To build this better world, accepting that different perspectives...even unrespected perspectives is increasingly difficult, given political gridlock, historical injustice and outrage culture. The ever shaky balance between our ideals to build a better world and the acknowledgement of our human limitations is so naked before us. And yet, development of ourselves and others may require holding that difficult axiom, that all speech does not have to be valued, but should be tolerated.

The quote above is attributed to a recent Atlantic article (https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/cancellation-unc-nikole-hannah-jones/618951/) regarding the denied tenure ship of Nikole Hannah-Jones. The denial’s reasons have not been released, but due to Hannah-Jones political work on the 1619 project, one has to consider if her politics misalignment to her university was the cause for the dismissal.

Authority and the scientific method seem to be the primary discussion points of Rauch’s work. Rauch makes the distinction between fact and opinion. Facts being replicable by persons, regardless of their identification with a marginalization or special interest group. Standing on the axiomatic principal of Popper’s falsifiability law, that science can only disprove, the implication is that science’s growth is largely from abandoning theory and perspectives that melt under scrutiny.

Bertrand Russell once wrote “order without authority” may well be the liberal science (p.57). Rauch attempts to couch arguments within the arguments of epistemology. Plato’s educational goal to inoculate the citizens with virtue and belief sounds reasonable. But with central authority comes the risk that continues into our time. Some beliefs may not be respected. Some may not even be allowed. Rauch’s work continues in the great liberal tradition of espousing an unshackled trust in freedom of speech and expression.

Examples of campus speaker cancellations, fatwas against apostates and continual distrust of freedom are from the 90s and early 2000’s, but the threat to freedom of speech from authorities is ever present. The political spectrum abounds with authorities who will not tolerate speech that insensitive, hurtful or biased. From totalitarian/despotic governments (Saudia Arabia, the People’s Republic of China) to the Marxist underpinnings of social theory (woke culture). Speaking harmfully is punishable. Social media’s value of rightness over truthfulness may be the most visible example of the liberal/humanitarian divide.

Judith Skhlar, a modern philosopher, states that what we value most is “not to harm”. And so with our societies growing connectedness, the everyday actions of all of us are increasingly under scrutiny. To build this better world, accepting that different perspectives...even unrespected perspectives is increasingly difficult, given political gridlock, historical injustice and outrage culture. The ever shaky balance between our ideals to build a better world and the acknowledgement of our human limitations is so naked before us. And yet, development of ourselves and others may require holding that difficult axiom, that all speech does not have to be valued, but should be tolerated.

Extraordinary. Possibly one of the best books I've ever read, and certainly the best argument I've ever read. Ferociously argued and cogently written. This does not deserve the relative obscurity it has fallen into. If any piece of writing on the nature and point of science deserves to be required reading for those entering higher education, it is this one.

One of my first in depth reads on the topic of free speech. He covers a lot of points with success in my opinion. I'll be looking at his other books as well.

informative

I'm not positive that the inquisitors are kindly.

This book could be described as a defence of freedom of speech, but I think that would be underselling it. It's more about how we, as a liberal and modern society, decide what is true and what is false.

In a short and extremely accessible introduction he explains how we have approached this problem through the ages, from the Greek Philosophers (who so nearly got it right) through the Catholic Inquisition (who got it oh so wrong!) before emerging after the Renaissance with enlightened tools like the scientific method and freedom of speech.

It challenges the reader first with questions which (these days) are fairly simple: why don't we give equal time to teach creationism as an alternative to evolution for example. Before moving into more challenging territory.

Written nearly 30 years ago, I can only see how this book has got more relevant. With a President that openly relies on "alternative facts"; conspiracy theories about COVID going mainstream; and an online culture where debate is settled by identity politics, we could all do with being reminded there is better way.

My only criticism of this book is that in places I found it overly repetitive. But other than that, I haven't come across a more complete, satisfying and unpolitical summary of why freedom of speech is so important for real meaningful progress.

In a short and extremely accessible introduction he explains how we have approached this problem through the ages, from the Greek Philosophers (who so nearly got it right) through the Catholic Inquisition (who got it oh so wrong!) before emerging after the Renaissance with enlightened tools like the scientific method and freedom of speech.

It challenges the reader first with questions which (these days) are fairly simple: why don't we give equal time to teach creationism as an alternative to evolution for example. Before moving into more challenging territory.

Written nearly 30 years ago, I can only see how this book has got more relevant. With a President that openly relies on "alternative facts"; conspiracy theories about COVID going mainstream; and an online culture where debate is settled by identity politics, we could all do with being reminded there is better way.

My only criticism of this book is that in places I found it overly repetitive. But other than that, I haven't come across a more complete, satisfying and unpolitical summary of why freedom of speech is so important for real meaningful progress.

I agree with much of what Rauch says here, and I applaud him for saying it. In particular, the point that “we must all take seriously the idea that any and all of us might, at any time, be wrong” (p. 45) is a crucial position to take in order to arrive at the truth. Likewise, his assertion that “Respect is no opinion’s birthright” (p. 120) is absolutely correct, and yet far too often ignored, in the interest of civility, as when it’s taken for granted that we should respect each other’s ideas. In fact, ideas don’t deserve respect at all; only people do, and only then until they act in such a way to lose that respect.

Rauch presents the guiding principles that “No one gets the final say” and that “No one has personal authority.” (p. 46), and he’s right; to claim otherwise is to slide down the path toward authoritarianism and illiberal restrictions on speech and even thought. The distinguishing ethic of liberal science is, according to Rauch, “that liberals believe they must check their beliefs, or submit them for checking, however sure they feel.” (p. 92) His advice on what to “do about people who have silly or offensive opinions and who haven’t bothered to submit to the rigors of public checking? Ignore them.” (p. 129) This is exactly the right answer. The purveyors of hatefulness and nonsense want attention more than anything, and they should be completely ignored - including, especially, by the media.

And yet… I do have a few concerns here. First is the fact that Rauch’s primary target is the extreme left and its “wokeness” (although that term wasn’t used in 1993 when this was written). While I’m sympathetic to this, and I certainly hope that those on the far left will read this book and take its criticism seriously, it’s fair to point out that the extreme right has long been far more guilty of the sins described here. The religious autocrats of the irrational right have been behaving this way for centuries, and dealing harshly with any attempt at opposition. Complaining that the pendulum has finally swung to where the left is also venturing into authoritarian territory does not exactly justify the excessive focus on them to the exclusion of the literal authoritarians on the right.

Second, I fear that Rauch puts too much faith in the “critical sorting system” (p. 145) that is supposed to elevate good ideas while allowing bad ones to die. Just as the invisible hand of the free market can’t be counted upon to create an economy that is beneficial to all members of society, neither does free speech absolutism ensure that we are making the world more free. It’s true that we don’t want the government imposing rules on which speech should be allowed, but there is some value in arranging incentives so that the most obnoxious speech is at the very least not rewarded, and should certainly not easily lead to positions of power. When there are so many people who simply refuse to play by the rules of the “science game” and accept the validation or rejection of their opinions by means of rational public debate, there is a real danger that the irrational on either the left or the right can simply take control of government. At that point the system of liberal science can be suppressed, and all the checking in the world won’t help.

And finally, even though we must allow for the possibility that we’re wrong, we nevertheless must act as if we’re right, until proven otherwise. Beliefs translate into public policies that make a real difference in our lives and the lives of others, so if we have good evidence that a conclusion is true, we have no reason to sit back and listen to the nonsense that opponents spew in response. Ignore them, yes, but also take actions that we believe actually make the world a better place, even if it means making laws or policies that might have to be modified later if it turns out that our conclusions were incorrect after all.

Again, I give credit to Rauch for the positions taken in this book, and it’s well worth reading by those of any political stripe. If there’s room to dispute some of the points made here, and I think there is, well then I expect Rauch would support our prerogative to do so.

Rauch presents the guiding principles that “No one gets the final say” and that “No one has personal authority.” (p. 46), and he’s right; to claim otherwise is to slide down the path toward authoritarianism and illiberal restrictions on speech and even thought. The distinguishing ethic of liberal science is, according to Rauch, “that liberals believe they must check their beliefs, or submit them for checking, however sure they feel.” (p. 92) His advice on what to “do about people who have silly or offensive opinions and who haven’t bothered to submit to the rigors of public checking? Ignore them.” (p. 129) This is exactly the right answer. The purveyors of hatefulness and nonsense want attention more than anything, and they should be completely ignored - including, especially, by the media.

And yet… I do have a few concerns here. First is the fact that Rauch’s primary target is the extreme left and its “wokeness” (although that term wasn’t used in 1993 when this was written). While I’m sympathetic to this, and I certainly hope that those on the far left will read this book and take its criticism seriously, it’s fair to point out that the extreme right has long been far more guilty of the sins described here. The religious autocrats of the irrational right have been behaving this way for centuries, and dealing harshly with any attempt at opposition. Complaining that the pendulum has finally swung to where the left is also venturing into authoritarian territory does not exactly justify the excessive focus on them to the exclusion of the literal authoritarians on the right.

Second, I fear that Rauch puts too much faith in the “critical sorting system” (p. 145) that is supposed to elevate good ideas while allowing bad ones to die. Just as the invisible hand of the free market can’t be counted upon to create an economy that is beneficial to all members of society, neither does free speech absolutism ensure that we are making the world more free. It’s true that we don’t want the government imposing rules on which speech should be allowed, but there is some value in arranging incentives so that the most obnoxious speech is at the very least not rewarded, and should certainly not easily lead to positions of power. When there are so many people who simply refuse to play by the rules of the “science game” and accept the validation or rejection of their opinions by means of rational public debate, there is a real danger that the irrational on either the left or the right can simply take control of government. At that point the system of liberal science can be suppressed, and all the checking in the world won’t help.

And finally, even though we must allow for the possibility that we’re wrong, we nevertheless must act as if we’re right, until proven otherwise. Beliefs translate into public policies that make a real difference in our lives and the lives of others, so if we have good evidence that a conclusion is true, we have no reason to sit back and listen to the nonsense that opponents spew in response. Ignore them, yes, but also take actions that we believe actually make the world a better place, even if it means making laws or policies that might have to be modified later if it turns out that our conclusions were incorrect after all.

Again, I give credit to Rauch for the positions taken in this book, and it’s well worth reading by those of any political stripe. If there’s room to dispute some of the points made here, and I think there is, well then I expect Rauch would support our prerogative to do so.

A passionate and well-articulated defense of free speech. Even though it was written thirty years ago it rings more true than ever. In Kindly Inquisitors Jonathan Rauch makes the case for countering bad ideas with better ones—starting with Plato's Republic! No idea is exempt from the public checking and sorting game.

In the United States it is clear that many people prefer sloppy, feel-good hashtag activism to intellectual liberal discourse. Normally this would be fine: the system is working if we can speak out and check others' ideas (and they can check ours). Instead, public criticism of certain notions is met with cries of "words of violence" and widespread moral outrage. That's par for the course, but in the digital age the price is higher when the mob moves against you. "Canceling" and "de-platforming" tactics are the new blacklisting. This is illiberal and is not an effective way to suppress ideas anyways!

Because this book was written before the Internet the topic is not explicitly addressed, though the related problem of misinformation is. Nevertheless, in my opinion, the Internet exacerbates the problem of misinformation and makes liberal intellectual discourse both easier and impossible. A group of teenagers in Macedonia can write an official-looking blog post saying that Hillary Clinton is in the hospital and cause doubt and speculation, the Syrian Electronic Army can hack a high-profile Twitter account and say that the White House is on fire (crashing the stock market), etc. How do we deal with literally fake news? Before you know it the article has been shared thousands of times and the damage is done. We are too naive if we think that everyone plays by the same rule we do. How does liberalism respond?

In the United States it is clear that many people prefer sloppy, feel-good hashtag activism to intellectual liberal discourse. Normally this would be fine: the system is working if we can speak out and check others' ideas (and they can check ours). Instead, public criticism of certain notions is met with cries of "words of violence" and widespread moral outrage. That's par for the course, but in the digital age the price is higher when the mob moves against you. "Canceling" and "de-platforming" tactics are the new blacklisting. This is illiberal and is not an effective way to suppress ideas anyways!

Because this book was written before the Internet the topic is not explicitly addressed, though the related problem of misinformation is. Nevertheless, in my opinion, the Internet exacerbates the problem of misinformation and makes liberal intellectual discourse both easier and impossible. A group of teenagers in Macedonia can write an official-looking blog post saying that Hillary Clinton is in the hospital and cause doubt and speculation, the Syrian Electronic Army can hack a high-profile Twitter account and say that the White House is on fire (crashing the stock market), etc. How do we deal with literally fake news? Before you know it the article has been shared thousands of times and the damage is done. We are too naive if we think that everyone plays by the same rule we do. How does liberalism respond?