You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

informative

medium-paced

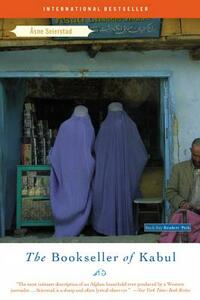

Rarely does one come across such a mature piece of journalism as Åsne Seierstad's "The Bookseller of Kabul". Written compellingly, the relatively short, episode-like stories from around the flat in Mikorayon, Kabul show both the glory and obscurity of life in Afghanistan. The true power of "The Bookseller of Kabul" lies in its ability to evoke a broad spectrum of feelings, ranging from the patriarchy-induced anger, grief for Leila's lost hopes, poignancy of unhappy love, bewilderment at Sharifa's ability to accept her new situation to bafflement by virtue of how an individual can take on vastly differing roles in different areas of their life, a sensation certainly present for the longest time after perusing the paperback. Though it is Sultan Khan who is the titular bookseller and - owing to the common practice in titling - the main character, the title of Å. Seierstad's piece seems to be an almost ironic take on Afghanistan's focus on a man's existence. As the head of the family, Sultan is expected to be the central being, in a way, of the book, around whom the narrative revolves. However, this is not entirely the case. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this aspect would be to recall a personal experience of commuting, whilst deep in the study of "My Mother Osama", and having it interrupted by a passenger asking whether this was Osama bin Laden's biography. Similarly, much of "The Bookseller of Kabul" touches on the subject of Sultan Khan's relatives, who are by and large women, and whose lives would likely have been led in half light, had it not been for a female author. As an intimate portrait of the Afghani, "The Bookseller of Kabul" is a publication worthy of treasuring profoundly.

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

sad

tense

medium-paced

adventurous

challenging

sad

medium-paced

emotional

informative

sad

fast-paced

Either the translation ruined the writing or the writing is just void of expression and feeling, but this book reads like a very dry newspaper article. It was interesting to get to know an Afghani family, but oh, it only reinforces my anger about the injustices women suffer every day in this part of the world.

challenging

emotional

informative

reflective

sad

Visiting Kabul after the fall of the Taliban, Norwegian journalist Asne Seierstad stumbles upon a bookshop. She strikes a conversation with the owner, a middle-aged man named Sultan Khan, who recounts the tyrannous reign of the Taliban and the destruction of his books by the Communists, Mujahideen and Taliban alike. Intrigued, Seierstad is eager to write about Sultan’s life and subsequently spends a handful of months with his family, most of whom cannot speak English. Her book is thus heavily reliant on Sultan and a couple of his kids as translators/interpreters. Though partly fictitious, this restricted communication has led to a poor, subpar portrayal of both the Khan family and broader Kabul society.

The blurb claims, “Seierstad steps back from the page and lets the Khans tell their stories”, and that “the result is a unique portrait of a family and a country.” I’m not sure what kind of “unique” reflection of Afghan life, culture and customs Seierstad intended to relay, but this book does nothing but stereotype, in fact I’m dubious as to how much of this book actually allowed the Khans to “tell their story”. I’d be pandemic-level surprised if this work is an accurate reflection of how the Khan’s feel about themselves, each other, and their culture.

Throughout the book, Seierstad maintains an obnoxious air of White Superiority and debases Afghans at almost every turn. When she isn’t portraying Afghan men as volatile, angry, polygyny-obsessed brutes, she’s portraying Afghan women as pathetic, brainless child brides who secretly loathe religion. If that wasn’t bad enough, she also goes on to argue that all Afghan men are religiously disturbed psychopaths that are simultaneously patriarchal and emasculated.

Plot-wise, there is none, as this book brands itself as non-fiction. Fair enough - but, like I mentioned above, I doubt the “characters” in this work would ever consent to such a deplorable, offensive representation or present themselves in such a derogatory way.

To say this book does a disservice to Afghan people and culture is the understatement of the century. Also, fun fact - the “Khan” family became political refugees and had to flee Afghanistan after the publication of this book because they felt so unsafe. Seierstad was also found guilty of defamation and failed to pay damages to the family. Naturally.

I’m really tired of non-PoCs with saviour complexes coming to our countries, “hearing” (read: misconstruing) our “stories” and profiting off our lives.

The blurb claims, “Seierstad steps back from the page and lets the Khans tell their stories”, and that “the result is a unique portrait of a family and a country.” I’m not sure what kind of “unique” reflection of Afghan life, culture and customs Seierstad intended to relay, but this book does nothing but stereotype, in fact I’m dubious as to how much of this book actually allowed the Khans to “tell their story”. I’d be pandemic-level surprised if this work is an accurate reflection of how the Khan’s feel about themselves, each other, and their culture.

Throughout the book, Seierstad maintains an obnoxious air of White Superiority and debases Afghans at almost every turn. When she isn’t portraying Afghan men as volatile, angry, polygyny-obsessed brutes, she’s portraying Afghan women as pathetic, brainless child brides who secretly loathe religion. If that wasn’t bad enough, she also goes on to argue that all Afghan men are religiously disturbed psychopaths that are simultaneously patriarchal and emasculated.

Plot-wise, there is none, as this book brands itself as non-fiction. Fair enough - but, like I mentioned above, I doubt the “characters” in this work would ever consent to such a deplorable, offensive representation or present themselves in such a derogatory way.

To say this book does a disservice to Afghan people and culture is the understatement of the century. Also, fun fact - the “Khan” family became political refugees and had to flee Afghanistan after the publication of this book because they felt so unsafe. Seierstad was also found guilty of defamation and failed to pay damages to the family. Naturally.

I’m really tired of non-PoCs with saviour complexes coming to our countries, “hearing” (read: misconstruing) our “stories” and profiting off our lives.

emotional

sad

I am torn with this book. I would definitely say that there is not anthropological merit to it considering her special "bi-gendered" creature (her words) stature. She rides a line between how an outside women is able to act and what an Afghan women is limited to. It is depressing to see the oxymoron that is life in this world. In one instance Sultan Khan talks of empowering women but then treats them in the traditional fashion - he only has his past with which to guide his actions.