Take a photo of a barcode or cover

29 reviews for:

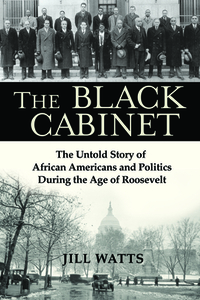

The Black Cabinet: The Untold Story of African Americans and Politics During the Age of Roosevelt

Jill Watts

29 reviews for:

The Black Cabinet: The Untold Story of African Americans and Politics During the Age of Roosevelt

Jill Watts

This is an excellent resource on a time in history with an impressive and courageous group of individuals who sought to even the odds in Washington D.C. by representing African Americans on a national level. The tragedy that such a group ever ended proves that we still have a long way to go.

I received a free copy of this book from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review.

I received a free copy of this book from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review.

This is a wonderful book that shines a light on a group of black people that worked tirelessly, in the White House, to get African Americans the rights they inherently deserve, in spite of segegation and Jim Crow. This book is packed with information that every American should be privy to.

The Black Cabinet was the unofficial name for a group of Black Americans who were public policy advisors (for black issues) during FDR’s presidency .

This book covers the black vote in America and how important it is today. It also covers the switch in political parties for black Americans and the foundation it laid for civil rights. There were over 100 members in the Cabinet, but this covers the most influential including Mary McLeod Bethune and Dr. Robert Weaver.

I feel like this should be part of the required curriculum in high school and college. The author did an outstanding job with research and presenting the facts as they were.

This book covers the black vote in America and how important it is today. It also covers the switch in political parties for black Americans and the foundation it laid for civil rights. There were over 100 members in the Cabinet, but this covers the most influential including Mary McLeod Bethune and Dr. Robert Weaver.

I feel like this should be part of the required curriculum in high school and college. The author did an outstanding job with research and presenting the facts as they were.

informative

slow-paced

Moderate: Racism, Violence

First and foremost, a large thank you to NetGalley, Jill Watts, Grove Atlantic, and Grove Press for providing me with a copy of this publication, which allows me to provide you with an unbiased review.

I stumbled upon this book by Jill Watts a while back and thought that it would make the perfect addition to my collection, as I seek to open my mind about all things related to politics and history, particularly those that were not as well-known. As race clashes rise to the surface once again on America, Watts takes the reader back in time to after the dust of the Civil War, and one president in particular who sought to begin offering a degree of racial equality. Watts explores how the freeing of the slaves and those who were oppressed came slowly to American society, so used to having the inequality in place. Watts hints that some of the post-War presidents flirted with the idea of advisors and those who could speak for the black population, though no one really gave much effort until Theodore Roosevelt during his time in the White House. Teddy opened some doors, but things within the Republican Party began to fray for the African American population, as it soon became apparent that Roosevelt was giving only lip service to the needs and desires of the black population. With the Great Depression and the ushering in of a new dawn with Franklin Roosevelt, there seemed to be hope, particularly when the new President Roosevelt wanted advisors within many of the government agencies who were African Americans, shaping the approach of service delivery as well as a different approach to how America might be run. While not a formal inner circle, there was a loose name given to this group, the Black Cabinet. This group would meet and their quasi-leader, Mary McLean Bethune, was a strong advocate, holding FDR and the larger government machine accountable. While the New Deal was being apportioned out, Bethune liaised regularly with FDR (and his wife) and kept up a rigorous speaking tour to rally citizens towards the rights of blacks in this new and adventurous country. This continued and Bethune stumped for FDR’s re-election happily, helping Democrats toss off the image of the party for slavery, as the roles were reversed. Bethune did all she could, using others within the Black Cabinet to help her, giving hope to a population who were so used to being oppressed. Watts shows how new issues were explored through the Black lens and FDR relied on Bethune and her advisors to offer solutions. However, as war rumbled in Europe, the New Deal began to show weakness, though FDR held firm to using Bethune’s power of drumming up support to ensure an unprecedented third term in the White House. With that, the neutrality that FDR pitched was in name only, as funds were shifted around to support a war effort. Bethune sought to capitalize on this, seeking black participation in all aspects of military life and integration as a key part of the entire process. Military officials balked and pushed back as much as they could, though FDR knew he would have to offer something or turn his back on Bethune and the Black Cabinet, sure to alienate the voting base they controlled. Into the 1940s, American sentiments shifted and there was no longer a New Deal sentiment. Watts closes her book out in the early days after FDR’s 1944 presidential victory. With the win, FDR sought to end the war, though his health ended him first. With his passing, so went the push for the Black Cabinet and strong advocacy for black rights. It did return in the form of other leaders, but Watts argues that none had the ear of or the inner connection to the African American population that FDR held. A powerful book and eye opening for those who enjoy this sort of piece. I’d recommended it to fans of US political history, as well as those who find race relations to their liking.

I won’t profess to being an expert at all on this subject and read it more out of interest. I enjoyed how Watts took the reader through the backstory of post-Civil War America and how it came together effectively to show the sentiments of the new ‘black’ population, those who mattered and were no longer simply chattel. The rise to importance of this race, seeking equality, can be seen in the early part of the book, though things were slow and somewhat stilted as the population (and politicians) sought to come to terms with this new attempted equality. Watts explores the interest FDR took in the movement and how he was kept in the loop repeatedly by those he felt could offer him a new ‘black’ perspective. Watts breaks things up along the FDR presidential elections, showing how important the black voice and vote became as time contained, with Mary McLean Bethune acting as a conduit throughout the process. With chapters that show the advancement (or reversion) of policies as they play into the hands of the black population, Watts shows how things wax and wane at different times. With decent chapter lengths and a great deal of information, the reader can digest the topics with ease, helped along by a chronological narrative that flows with ease. Watts develops her strong points throughout and shows that FDR was a harbinger for better race relations in the United States, though there was surely much that needed to be done. However, he took the black voice seriously, not pretending to speak for them, but using some of their own to speak to him. Brilliantly penned and something I will return to read again, of that I am sure.

Kudos, Madam Watts, for shedding such a needed light on the topic at hand. I learned so very much from this book and cannot wait to try more of your work.

Love/hate the review? An ever-growing collection of others appears at:

http://pecheyponderings.wordpress.com/

A Book for All Seasons, a different sort of Book Challenge: https://www.goodreads.com/group/show/248185-a-book-for-all-seasons

I stumbled upon this book by Jill Watts a while back and thought that it would make the perfect addition to my collection, as I seek to open my mind about all things related to politics and history, particularly those that were not as well-known. As race clashes rise to the surface once again on America, Watts takes the reader back in time to after the dust of the Civil War, and one president in particular who sought to begin offering a degree of racial equality. Watts explores how the freeing of the slaves and those who were oppressed came slowly to American society, so used to having the inequality in place. Watts hints that some of the post-War presidents flirted with the idea of advisors and those who could speak for the black population, though no one really gave much effort until Theodore Roosevelt during his time in the White House. Teddy opened some doors, but things within the Republican Party began to fray for the African American population, as it soon became apparent that Roosevelt was giving only lip service to the needs and desires of the black population. With the Great Depression and the ushering in of a new dawn with Franklin Roosevelt, there seemed to be hope, particularly when the new President Roosevelt wanted advisors within many of the government agencies who were African Americans, shaping the approach of service delivery as well as a different approach to how America might be run. While not a formal inner circle, there was a loose name given to this group, the Black Cabinet. This group would meet and their quasi-leader, Mary McLean Bethune, was a strong advocate, holding FDR and the larger government machine accountable. While the New Deal was being apportioned out, Bethune liaised regularly with FDR (and his wife) and kept up a rigorous speaking tour to rally citizens towards the rights of blacks in this new and adventurous country. This continued and Bethune stumped for FDR’s re-election happily, helping Democrats toss off the image of the party for slavery, as the roles were reversed. Bethune did all she could, using others within the Black Cabinet to help her, giving hope to a population who were so used to being oppressed. Watts shows how new issues were explored through the Black lens and FDR relied on Bethune and her advisors to offer solutions. However, as war rumbled in Europe, the New Deal began to show weakness, though FDR held firm to using Bethune’s power of drumming up support to ensure an unprecedented third term in the White House. With that, the neutrality that FDR pitched was in name only, as funds were shifted around to support a war effort. Bethune sought to capitalize on this, seeking black participation in all aspects of military life and integration as a key part of the entire process. Military officials balked and pushed back as much as they could, though FDR knew he would have to offer something or turn his back on Bethune and the Black Cabinet, sure to alienate the voting base they controlled. Into the 1940s, American sentiments shifted and there was no longer a New Deal sentiment. Watts closes her book out in the early days after FDR’s 1944 presidential victory. With the win, FDR sought to end the war, though his health ended him first. With his passing, so went the push for the Black Cabinet and strong advocacy for black rights. It did return in the form of other leaders, but Watts argues that none had the ear of or the inner connection to the African American population that FDR held. A powerful book and eye opening for those who enjoy this sort of piece. I’d recommended it to fans of US political history, as well as those who find race relations to their liking.

I won’t profess to being an expert at all on this subject and read it more out of interest. I enjoyed how Watts took the reader through the backstory of post-Civil War America and how it came together effectively to show the sentiments of the new ‘black’ population, those who mattered and were no longer simply chattel. The rise to importance of this race, seeking equality, can be seen in the early part of the book, though things were slow and somewhat stilted as the population (and politicians) sought to come to terms with this new attempted equality. Watts explores the interest FDR took in the movement and how he was kept in the loop repeatedly by those he felt could offer him a new ‘black’ perspective. Watts breaks things up along the FDR presidential elections, showing how important the black voice and vote became as time contained, with Mary McLean Bethune acting as a conduit throughout the process. With chapters that show the advancement (or reversion) of policies as they play into the hands of the black population, Watts shows how things wax and wane at different times. With decent chapter lengths and a great deal of information, the reader can digest the topics with ease, helped along by a chronological narrative that flows with ease. Watts develops her strong points throughout and shows that FDR was a harbinger for better race relations in the United States, though there was surely much that needed to be done. However, he took the black voice seriously, not pretending to speak for them, but using some of their own to speak to him. Brilliantly penned and something I will return to read again, of that I am sure.

Kudos, Madam Watts, for shedding such a needed light on the topic at hand. I learned so very much from this book and cannot wait to try more of your work.

Love/hate the review? An ever-growing collection of others appears at:

http://pecheyponderings.wordpress.com/

A Book for All Seasons, a different sort of Book Challenge: https://www.goodreads.com/group/show/248185-a-book-for-all-seasons

It’s hard to believe the level of racism present in the United States less than a century ago. From the backroads to the halls of government, there were restrictions so that the races would not have to mix. Stir in the Roosevelt years of the Great Depression and you begin to understand the issues that challenged those who dedicated their time and energy to create equality among all Americans.

The Black Cabinet was the unofficial name for a brain trust of African Americans during the presidential years of FDR. Initially, a few were given token hires within the government where they were supposed to be able to give their insight and ensure both blacks and whites received aid during the Great Depression. They themselves experienced racism in their departments. Non-whites were not allowed to eat in the department dining room, and at one point, the entire secretarial pool refused to work for one of these pioneers. These were the years when the Democrats and Republicans battled over votes of the African American community, even though both sides promised much and delivered little. Those in the Black Cabinet battled a President who would listen yet hesitated to move forward due to political issues, and administrators who marginalized and blocked their efforts. Yet though there were many setbacks, there were accomplishments that are described in the book.

Author Jill Watts provides deep detail of the people involved, painting a picture of their backgrounds and how they ended up becoming a part of the Black Cabinet. While most of us remember reading the skeletal history of the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal, never before have I had the opportunity to be able to learn about this slice of history, one that had great effect upon the United States. The author backs up her work with a long section of references as well as an extensive listing of books and pamphlets. The research is impressive and adds many small items that enrich the story. Though the book is long the detail keeps it interesting. Five stars.

My thanks to NetGalley and Grove Press for a complimentary ebook of this title.

The Black Cabinet was the unofficial name for a brain trust of African Americans during the presidential years of FDR. Initially, a few were given token hires within the government where they were supposed to be able to give their insight and ensure both blacks and whites received aid during the Great Depression. They themselves experienced racism in their departments. Non-whites were not allowed to eat in the department dining room, and at one point, the entire secretarial pool refused to work for one of these pioneers. These were the years when the Democrats and Republicans battled over votes of the African American community, even though both sides promised much and delivered little. Those in the Black Cabinet battled a President who would listen yet hesitated to move forward due to political issues, and administrators who marginalized and blocked their efforts. Yet though there were many setbacks, there were accomplishments that are described in the book.

Author Jill Watts provides deep detail of the people involved, painting a picture of their backgrounds and how they ended up becoming a part of the Black Cabinet. While most of us remember reading the skeletal history of the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal, never before have I had the opportunity to be able to learn about this slice of history, one that had great effect upon the United States. The author backs up her work with a long section of references as well as an extensive listing of books and pamphlets. The research is impressive and adds many small items that enrich the story. Though the book is long the detail keeps it interesting. Five stars.

My thanks to NetGalley and Grove Press for a complimentary ebook of this title.

Book provided by NetGalley

You can watch my reading vlog and review on my YouTube Channel;

4.5/5 stars

I approached Jill Watt’s book with a little trepidation. I was intrigued by the concept and the topic because it’s not something I’ve ever heard of. History is not my profession, and I know there’s always more for me to learn. As the publication data approached I grew wary of reading it. It wasn’t that I wasn’t interested in learning about what was in it; I was just worried about my ability to comprehend what I read. Some of these more academic books can be really difficult to get into and read through. It doesn’t help that I’m a better reader when listening to audiobooks. Lucky for me, May was a tough month, and I was late to reading this. By the time I got to it the book was published. The audiobook was out. So I chose to listen to it. And I’m glad I did because I ended loving the audiobook. What’s more, I also think this would probably make a fantastic book to read physically as well.

The black cabinet first informally started in the age of Theodore Roosevelt, not long after the reconstruction when we begin to see a few black figures begin to get a voice in the federal government. Unfortunately this is also the time of the reconstruction when the federal government was supposed to be keeping the South from implementing things like Jim Crow, basically forcing them to follow the law rather than be resistant as they were prone to do.

Unfortunately, black Americans proved to be more trouble than it was worth, so the Republican party decided to let it go. Any issues to do with black Americans was put to the sideline. Voices were ignored and after Theodore Roosevelt left the office the few people in the black cabinet were removed from the federal government and lost any sway they might have had. A few presidencies passed and we begin to see a few voices pushing back on this idea that the Republican party as the party of African Americans.

African-Americans may have played a part in the election of Woodrow Wilson, but that democratic win was also in part due to a third party candidate. Around the time of FDR we begin to see black Americans really pushing for his election. We see people thinking that this might be the candidate who can represent them and can make things happen.

When he finally is elected, we begin to see a few African Americans again in positions of power. They weren’t a cohesive group of people, nor was it anything formal orchestrated by FDR. These were just a few individuals placed throughout the federal government or in organizations tied to the government. In fact fractions begin to form as certain African Americans push back against each other in the fight for civil rights and equality.

Income Mary Bethune and things change. Where there was a fraction there was now a group of people held together by this amazing woman who was capable of inspiring and leading them into standing together. Across FDR’s several administrations, they would go on to decrease black unemployment and increase funding in black American education. They fought for in the military, but this battle was not completed before FDR’s death in his fourth term.

While by the end of the book we may begin to feel a bit disenfranchised by all the ways in which they failed to get everything they had strove for, Watts still helps us recognize that despite their shortcomings they played an immeasurable part in the move towards civil rights. They set the stage for Kennedy who introduced the civil Rights act. Even before him, FDR’s successor would go on to desegregate the military, something FDR fought against out of fear or apathy. Of course, eventually Johnson would sign into law the civil rights act. Johnson had a had a relationship with Bethune before he took office, and it is impossible to measure the effect that kind of connection may have had on him. Many of the civil rights figures, who you may be more familiar with, were inspired by people like Mary Bethune.

In all of this, FDR is often remembered as being responsible for putting together this group of people to help advise him. However, that is not the case. The reason in which they could not get everything they wanted was because of FDR and his cabinet. FDR may not have played an active role in fighting them, but he stood by and let the rest of his administration do that for him. Either out of a desire to prevent it or a apathy toward African American, he would consistently fail to act. Any of the few actions that may have happened under his presidency were done very much against his will. To him the problems about the Americans were too much of a risk.

In his death he may have been memorialized as this civil rights figure, but it is important to recognize that the progress of his time was not due to him. It was due to this group of people who fought him every step of the way. While his untimely death (well he did get elected four times) may have caused a slight rewriting of history, it’s important to remember that this was because of a group of African Americans who put themselves at risk to fight for equality and they deserve to be remembered. What’s more, I think this book is very relevant today when we think about the existing inequalities whose existence is similarly denied or marked as unavoidable. What’s more, it speaks to the need for representation. When people say why do we need a women of color VP, this is why. They aren’t just overlooked when qualified, their viewpoints are necessary to truly overcome our inequalities.

Now the book itself was fantastic. There were times where I got a bit lost. A part of that is just because it is very detailed, and there are a lot of names we need to remember. Mary Bethune is just a leader here, and there are four or five other important figures who you might want to take note of. I mentioned them in my video review and vlog. Watts begins the book with an introduction where she talks about this basic setup of Bethune guiding the black cabinet and her relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt and how FDR really played no part in the black cabinet. However, I would have liked if she had mentioned the other key figures there too just so that I would have known to keep an eye out for those figures. When we’re talking about so many different individuals in history, it’s easy for these more significant individuals to get lost in the details. Once I identified them I did a better job keeping up, but that was really my only complaint in this book.

However, even with that one complaint I never stopped being thoroughly engaged. I enjoyed reading this. I did not want to stop; I wanted to find out what happened next even if have a general idea of what was to come. I was also just very excited to learn about history and politics. I’m excited to continue learning and to find other resources about the past. I’m interested in learning more about the civil rights movement and the different people who played a role in the past and the intricacies that are often lost in the history books. For that, I applaud Watts.

I adore this book, and I’m so happy that I read it. Any hesitation I had about it being too academic or too difficult to read was wrong. I highly recommend this book if you have any interest in the history of civil rights movement or politics because it is fascinating for all of those reasons.

You can watch my reading vlog and review on my YouTube Channel;

4.5/5 stars

I approached Jill Watt’s book with a little trepidation. I was intrigued by the concept and the topic because it’s not something I’ve ever heard of. History is not my profession, and I know there’s always more for me to learn. As the publication data approached I grew wary of reading it. It wasn’t that I wasn’t interested in learning about what was in it; I was just worried about my ability to comprehend what I read. Some of these more academic books can be really difficult to get into and read through. It doesn’t help that I’m a better reader when listening to audiobooks. Lucky for me, May was a tough month, and I was late to reading this. By the time I got to it the book was published. The audiobook was out. So I chose to listen to it. And I’m glad I did because I ended loving the audiobook. What’s more, I also think this would probably make a fantastic book to read physically as well.

The black cabinet first informally started in the age of Theodore Roosevelt, not long after the reconstruction when we begin to see a few black figures begin to get a voice in the federal government. Unfortunately this is also the time of the reconstruction when the federal government was supposed to be keeping the South from implementing things like Jim Crow, basically forcing them to follow the law rather than be resistant as they were prone to do.

Unfortunately, black Americans proved to be more trouble than it was worth, so the Republican party decided to let it go. Any issues to do with black Americans was put to the sideline. Voices were ignored and after Theodore Roosevelt left the office the few people in the black cabinet were removed from the federal government and lost any sway they might have had. A few presidencies passed and we begin to see a few voices pushing back on this idea that the Republican party as the party of African Americans.

African-Americans may have played a part in the election of Woodrow Wilson, but that democratic win was also in part due to a third party candidate. Around the time of FDR we begin to see black Americans really pushing for his election. We see people thinking that this might be the candidate who can represent them and can make things happen.

When he finally is elected, we begin to see a few African Americans again in positions of power. They weren’t a cohesive group of people, nor was it anything formal orchestrated by FDR. These were just a few individuals placed throughout the federal government or in organizations tied to the government. In fact fractions begin to form as certain African Americans push back against each other in the fight for civil rights and equality.

Income Mary Bethune and things change. Where there was a fraction there was now a group of people held together by this amazing woman who was capable of inspiring and leading them into standing together. Across FDR’s several administrations, they would go on to decrease black unemployment and increase funding in black American education. They fought for in the military, but this battle was not completed before FDR’s death in his fourth term.

While by the end of the book we may begin to feel a bit disenfranchised by all the ways in which they failed to get everything they had strove for, Watts still helps us recognize that despite their shortcomings they played an immeasurable part in the move towards civil rights. They set the stage for Kennedy who introduced the civil Rights act. Even before him, FDR’s successor would go on to desegregate the military, something FDR fought against out of fear or apathy. Of course, eventually Johnson would sign into law the civil rights act. Johnson had a had a relationship with Bethune before he took office, and it is impossible to measure the effect that kind of connection may have had on him. Many of the civil rights figures, who you may be more familiar with, were inspired by people like Mary Bethune.

In all of this, FDR is often remembered as being responsible for putting together this group of people to help advise him. However, that is not the case. The reason in which they could not get everything they wanted was because of FDR and his cabinet. FDR may not have played an active role in fighting them, but he stood by and let the rest of his administration do that for him. Either out of a desire to prevent it or a apathy toward African American, he would consistently fail to act. Any of the few actions that may have happened under his presidency were done very much against his will. To him the problems about the Americans were too much of a risk.

In his death he may have been memorialized as this civil rights figure, but it is important to recognize that the progress of his time was not due to him. It was due to this group of people who fought him every step of the way. While his untimely death (well he did get elected four times) may have caused a slight rewriting of history, it’s important to remember that this was because of a group of African Americans who put themselves at risk to fight for equality and they deserve to be remembered. What’s more, I think this book is very relevant today when we think about the existing inequalities whose existence is similarly denied or marked as unavoidable. What’s more, it speaks to the need for representation. When people say why do we need a women of color VP, this is why. They aren’t just overlooked when qualified, their viewpoints are necessary to truly overcome our inequalities.

Now the book itself was fantastic. There were times where I got a bit lost. A part of that is just because it is very detailed, and there are a lot of names we need to remember. Mary Bethune is just a leader here, and there are four or five other important figures who you might want to take note of. I mentioned them in my video review and vlog. Watts begins the book with an introduction where she talks about this basic setup of Bethune guiding the black cabinet and her relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt and how FDR really played no part in the black cabinet. However, I would have liked if she had mentioned the other key figures there too just so that I would have known to keep an eye out for those figures. When we’re talking about so many different individuals in history, it’s easy for these more significant individuals to get lost in the details. Once I identified them I did a better job keeping up, but that was really my only complaint in this book.

However, even with that one complaint I never stopped being thoroughly engaged. I enjoyed reading this. I did not want to stop; I wanted to find out what happened next even if have a general idea of what was to come. I was also just very excited to learn about history and politics. I’m excited to continue learning and to find other resources about the past. I’m interested in learning more about the civil rights movement and the different people who played a role in the past and the intricacies that are often lost in the history books. For that, I applaud Watts.

I adore this book, and I’m so happy that I read it. Any hesitation I had about it being too academic or too difficult to read was wrong. I highly recommend this book if you have any interest in the history of civil rights movement or politics because it is fascinating for all of those reasons.

The Black Cabinet is a history of the informal group of Black federal employees who worked within FDR’s New Deal agencies in order to influence them to help Black Americans. They helped ensure that Black people were hired by New Deal jobs programs like the WPA and the CCC. This history also tracks the history of the Black vote shifting from the party of Lincoln to the party of Roosevelt.

The Black Cabinet in 1938

Republicans took the Black vote for granted, believing they were still owed for Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation sixty years after it happened. However, Black people were devastated by the Depression and the GOP philosophy of limited government made it worse. With FDR, they saw a belief in an activist, involved government. Wisely, they reasoned that a government willing to regulate business to protect workers could become willing to regulate in order to protect civil rights while a party that believed in keeping its hands off could never come around to using the law to guarantee the rights of Black people.

With amazing details such as how a manicurist made the initial personal connection that led to Black leaders agreeing to support the Democratic Party, a party deeply associated with slavery and the Klan. They believed by helping Democrats win, they could influence policy and their gamble paid off, though not nearly so well as they hoped.

The Black Cabinet is fascinating, full of the small personal details that make history so engrossing. It also shows the throughline of civil rights activism throughout the 20th century. Fans of FDR will probably be disappointed. He is so often a distant figure, one who is most consistent in reluctance to lead on civil rights when he was focused on the Depression and World War II. Eleanor is far more active and has a much bigger role in this history. It is definitely a history of two steps forward and one step back – as is the history of Black liberation.

I would recommend The Black Cabinet to anyone interested in the history of civil rights and Black liberation. The New Deal played a huge part in building the middle class and middle class wealth such as housing equity and more. The New Deal did far less for Black people, creating a wealth gap that continues to this day. But imagine if the New Deal had gone forward without the tempering influence of The Black Cabinet.

I received an e-galley of The Black Cabinet from the publisher through Edelweiss.

https://tonstantweaderreviews.wordpress.com/2020/08/27/9780802129109/

The Black Cabinet in 1938

Republicans took the Black vote for granted, believing they were still owed for Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation sixty years after it happened. However, Black people were devastated by the Depression and the GOP philosophy of limited government made it worse. With FDR, they saw a belief in an activist, involved government. Wisely, they reasoned that a government willing to regulate business to protect workers could become willing to regulate in order to protect civil rights while a party that believed in keeping its hands off could never come around to using the law to guarantee the rights of Black people.

With amazing details such as how a manicurist made the initial personal connection that led to Black leaders agreeing to support the Democratic Party, a party deeply associated with slavery and the Klan. They believed by helping Democrats win, they could influence policy and their gamble paid off, though not nearly so well as they hoped.

The Black Cabinet is fascinating, full of the small personal details that make history so engrossing. It also shows the throughline of civil rights activism throughout the 20th century. Fans of FDR will probably be disappointed. He is so often a distant figure, one who is most consistent in reluctance to lead on civil rights when he was focused on the Depression and World War II. Eleanor is far more active and has a much bigger role in this history. It is definitely a history of two steps forward and one step back – as is the history of Black liberation.

I would recommend The Black Cabinet to anyone interested in the history of civil rights and Black liberation. The New Deal played a huge part in building the middle class and middle class wealth such as housing equity and more. The New Deal did far less for Black people, creating a wealth gap that continues to this day. But imagine if the New Deal had gone forward without the tempering influence of The Black Cabinet.

I received an e-galley of The Black Cabinet from the publisher through Edelweiss.

https://tonstantweaderreviews.wordpress.com/2020/08/27/9780802129109/

Very competent historical overview of the African American shadow cabinet in the Roosevelt administration. Naturally this overlaps with the general history of African Americans in the US in the 30’s and 40’s. It’s not a slim volume so there really is quite a lot of depth here, although the story is spread among a host of characters so there is not a huge amount of depth to any of the individuals that are covered.