Take a photo of a barcode or cover

This was a re-read that I wanted to revisit after a friend's reaction to the book. I wanted to explore the book again, and try to analyze why I like the book as a whole, despite not liking the ending much. I guess it would be better to say I am not comfortable with the ending.

I could not read this right before Christmas, as I remembered it was a little too emotionally demanding for that. So I read it after Christmas. I still love the book. I don't know for sure whether it's related to my survival from my own somewhat dysfunctional family, my fascination with reading about a "gifted" individual's struggles, or what, but this book has never failed to move me and provoke deep thought.

I spent a lot of time this time around pondering the differences between Asher, with whom I feel very sympathetic, despite my disagreement with his choices and especially his self-centeredness, and Danny (from The Promise and The Chosen) who is similarly profoundly gifted, and similarly rejects his Hasidic family in a painful way, but who on the whole seems to me more giving, better adjusted, less self-centered. Is this why Danny's father took the tremendously difficult step of treating his son with silence for years to teach him compassion? Does that explain the difference in outcomes? Or is it that intellectual giftedness in itself is more acceptable to the Jewish tradition than giftedness in art? Even though Danny leaves the Hasidic tradition that would have him follow his father as rebbe, and becomes a psychiatrist instead, his childhood brilliance earned him respect and honor in yeshiva and other areas. Could that be the difference? Or is Jacob Kahn correct, in that a great artist must be fundamentally selfish and self-centered? Is there, or could there have been, some way for Asher to reconcile his art with his family in a less painful way?

I don't know, but I am still deeply moved by this book, and despite my discomfort with the ending, I know I will read it again. I still hold that Chaim Potok is one of the greatest novelists of our century.

I could not read this right before Christmas, as I remembered it was a little too emotionally demanding for that. So I read it after Christmas. I still love the book. I don't know for sure whether it's related to my survival from my own somewhat dysfunctional family, my fascination with reading about a "gifted" individual's struggles, or what, but this book has never failed to move me and provoke deep thought.

I spent a lot of time this time around pondering the differences between Asher, with whom I feel very sympathetic, despite my disagreement with his choices and especially his self-centeredness, and Danny (from The Promise and The Chosen) who is similarly profoundly gifted, and similarly rejects his Hasidic family in a painful way, but who on the whole seems to me more giving, better adjusted, less self-centered. Is this why Danny's father took the tremendously difficult step of treating his son with silence for years to teach him compassion? Does that explain the difference in outcomes? Or is it that intellectual giftedness in itself is more acceptable to the Jewish tradition than giftedness in art? Even though Danny leaves the Hasidic tradition that would have him follow his father as rebbe, and becomes a psychiatrist instead, his childhood brilliance earned him respect and honor in yeshiva and other areas. Could that be the difference? Or is Jacob Kahn correct, in that a great artist must be fundamentally selfish and self-centered? Is there, or could there have been, some way for Asher to reconcile his art with his family in a less painful way?

I don't know, but I am still deeply moved by this book, and despite my discomfort with the ending, I know I will read it again. I still hold that Chaim Potok is one of the greatest novelists of our century.

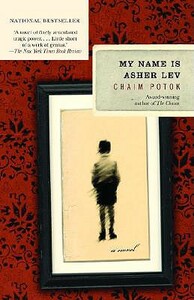

A book about a young boy struggling to balance his Orthodox Jewish upbringing with his artistic abilities.

I've read a number of Potok's books and am always fascinated with the way that he is able to introduce the reader into Jewish culture (something I am not overly familiar with) without "explaining" everything constantly.

This book in particular, and its sequel, I enjoyed for the references to art (and its production) they contain. Art too is a culture that one must be introduced to (and one that I am familiar with). This novel is an interesting trip into the mind of an artist.

I've read a number of Potok's books and am always fascinated with the way that he is able to introduce the reader into Jewish culture (something I am not overly familiar with) without "explaining" everything constantly.

This book in particular, and its sequel, I enjoyed for the references to art (and its production) they contain. Art too is a culture that one must be introduced to (and one that I am familiar with). This novel is an interesting trip into the mind of an artist.

emotional

inspiring

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

This is a book I picked up in Marlborough, NH, at a little used bookstore, also while on my New England vacation. I'd heard many people say how much they loved this book, so when I found it waiting for me on a step stool, I figured I'd take it with me.

I guess it was a coincidence that "Any Bitter Thing" had so many Catholic themes while "My Name is Asher Lev" portrays the life of a Hasidic Jew who loves to paint. So, with that little sidenote, let me tell you what I thought of the book.

I have to say that while I was charmed Chaim Potok's writing style, where everyone who's jewish seems to repeat what is said by another Jew, the message of the book is one I find hard to identify with. I found myself more aligned to Aryeh, Asher's father, than to Asher himself. Asher had this urge, I guess you could say, to paint, to study art, to learn about the artistic world that was very different from the world of Hasidism. He could not control it, and in the process he created magnificent art that unintentionally, but knowingly shocked and offended and hurt many of the people he loved. Now that is something I have a hard time understanding, so I'm a bit torn as to how to identify with the author's message. Asher had the chance to avoid causing this anguish, and you wonder if remaining uncompromising to what you think is necessary really justifies your actions.

What I loved about the book was the explanation of artists' motives and personality, some of the history of art, the spirituality of Hasidic Jews, the devotion to the Torah of the Lev family, the author's imagery and use of emotion.

The climax of the book is a tense, tense read, my friends. Not unlike the well-known train wreck you know is going to happen, but can't avoid watching. The last chapter of the book is fantastic.

I guess it was a coincidence that "Any Bitter Thing" had so many Catholic themes while "My Name is Asher Lev" portrays the life of a Hasidic Jew who loves to paint. So, with that little sidenote, let me tell you what I thought of the book.

I have to say that while I was charmed Chaim Potok's writing style, where everyone who's jewish seems to repeat what is said by another Jew, the message of the book is one I find hard to identify with. I found myself more aligned to Aryeh, Asher's father, than to Asher himself. Asher had this urge, I guess you could say, to paint, to study art, to learn about the artistic world that was very different from the world of Hasidism. He could not control it, and in the process he created magnificent art that unintentionally, but knowingly shocked and offended and hurt many of the people he loved. Now that is something I have a hard time understanding, so I'm a bit torn as to how to identify with the author's message. Asher had the chance to avoid causing this anguish, and you wonder if remaining uncompromising to what you think is necessary really justifies your actions.

What I loved about the book was the explanation of artists' motives and personality, some of the history of art, the spirituality of Hasidic Jews, the devotion to the Torah of the Lev family, the author's imagery and use of emotion.

The climax of the book is a tense, tense read, my friends. Not unlike the well-known train wreck you know is going to happen, but can't avoid watching. The last chapter of the book is fantastic.

It's been years since I last read this fine tale from Chaim Potok. Asher Lev is the child of Ladover Hasid parents, living in a closed Jewish community in Brooklyn. Asher's father works for the Rebbe, the community's religious leader, traveling as the Rebbe's "voice" to Ladover settlements around the world. He is deeply political, and impatient with anything or anyone who interferes with the great work he is a part of. So when Asher begins at an early age to demonstrate a remarkable ability to draw and paint, his parents are horrified. Their religion has no place for "nonsense" like art; it is part of the goyim, that other world outside their community. Yet Asher cannot stop himself from drawing... in the Yeshiva school, in the scores of notebooks, pictures of his world and its people. His mother stands between Asher, her difficult son, and his increasingly angry father. Asher's refusal to give up his art leads to a momentous moment--the intercession of the Rebbe in his future. Astoundingly, the Rebbe brings Asher together with Jacob Kahn, a great sculptor and painter, who becomes Asher's teacher and mentor.

Potok's story of the birth and growth of a great artist, from such unlikely beginnings, is fascinating and moving. The author admirably conveys the insular Hasidic movement, and looks as clear-eyed at its warmth and strong values, as at its prejudices and repressions. Asher's journey culminates in his creation of world-shaking paintings that forever separate him from his community and turn him into a pariah--yet their creation seems inevitable. Potok can be addictive. I strongly recommend *The Chosen*. And if you read this book, you may want to read the second book, *The Gift of Asher Lev*.

Potok's story of the birth and growth of a great artist, from such unlikely beginnings, is fascinating and moving. The author admirably conveys the insular Hasidic movement, and looks as clear-eyed at its warmth and strong values, as at its prejudices and repressions. Asher's journey culminates in his creation of world-shaking paintings that forever separate him from his community and turn him into a pariah--yet their creation seems inevitable. Potok can be addictive. I strongly recommend *The Chosen*. And if you read this book, you may want to read the second book, *The Gift of Asher Lev*.

I've been a fan of Chaim Potok's since high school. I don't know why it took me so long to read Asher Lev. I've heard about it for years. It's a moving story. It made me aware of all the things I don't know about art. Made me want to take some classes. He has extraordinary talent. I found myself wondering, as a non-artist, how the average artist sees and experiences the world.

I can't even begin to categorize all the feelings that this book elicited. It's a beautiful, hard book, and I wish I'd read it years ago.

I have only just begun to read My name is Asher Lev, and by page 20, I already know that this is one I will read slowly so as not to miss anything, in the writing and in the story.

Asher Lev was the juncture point of two significant family lines, the apex, as it were, of a triangle seminal with Jewish potentiality and freighted with Jewish responsibility. But he was also born with a gift.

But he was also born with a gift? But? Not and?

What an introduction to the narrator and his story.

Asher's gift was drawing. His mother praised his early efforts but constantly pushed him to draw pretty things. His father, a serious Hassidic Jew who worked for the Rabbi, wanted him to outgrow his childish hobby.

When Asher was six, his mother turned very sick. Asher tried to cheer her up by showing her a picture, not one filled with black swirls and angry eyes that he had been drawing, but one with pretty birds and flowers he created for her.

It backfired. That night, he had this conversation with his father:

"No one likes my drawings," I said through a fog of half sleep. "My drawings don't help."

My father said nothing.

"I don't like to feel this way, Papa."

Gently, my father put his hand on my cheek.

"It's not a pretty world, Papa."

"I've noticed," my father said softly.

His mother finally made it out of bed to the living room, where she sat motionless and slept. Asher drew her. Then he noticed his father watching him.

I had no idea how long he had been standing in the doorway....There was fascination and perplexity on his face. He seemed awed and angry and confused and dejected, all at the same time.

That night, when his father once again said he wished Asher wouldn't spend all his time drawing, this is how Asher replied:

"I wanted to draw and light and the dark."

Somehow, this experience made him hopeful. Instead of lamenting that his drawings couldn't help, this is how he felt:

I would put all the world into light and shade, bring life to all the wide and tired world. It did not seem an impossible thing to do.

My heart starts to break.

Asher Lev was the juncture point of two significant family lines, the apex, as it were, of a triangle seminal with Jewish potentiality and freighted with Jewish responsibility. But he was also born with a gift.

But he was also born with a gift? But? Not and?

What an introduction to the narrator and his story.

Asher's gift was drawing. His mother praised his early efforts but constantly pushed him to draw pretty things. His father, a serious Hassidic Jew who worked for the Rabbi, wanted him to outgrow his childish hobby.

When Asher was six, his mother turned very sick. Asher tried to cheer her up by showing her a picture, not one filled with black swirls and angry eyes that he had been drawing, but one with pretty birds and flowers he created for her.

It backfired. That night, he had this conversation with his father:

"No one likes my drawings," I said through a fog of half sleep. "My drawings don't help."

My father said nothing.

"I don't like to feel this way, Papa."

Gently, my father put his hand on my cheek.

"It's not a pretty world, Papa."

"I've noticed," my father said softly.

His mother finally made it out of bed to the living room, where she sat motionless and slept. Asher drew her. Then he noticed his father watching him.

I had no idea how long he had been standing in the doorway....There was fascination and perplexity on his face. He seemed awed and angry and confused and dejected, all at the same time.

That night, when his father once again said he wished Asher wouldn't spend all his time drawing, this is how Asher replied:

"I wanted to draw and light and the dark."

Somehow, this experience made him hopeful. Instead of lamenting that his drawings couldn't help, this is how he felt:

I would put all the world into light and shade, bring life to all the wide and tired world. It did not seem an impossible thing to do.

My heart starts to break.

This is a very thoughtful and thought-provoking book about the tension between artistic expression and cultural environment. Potok translates this into the most personal of settings n a truly heart-rending tale.

challenging

emotional

inspiring

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

N/A

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No