Take a photo of a barcode or cover

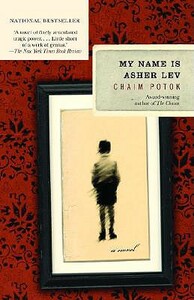

Honestly, not a terrible book. A little slow in the middle and the ending is super sad, but I still enjoyed it.

I am haunted and inspired; horrified and in awe all at the same time. Potok moved my soul with this masterpiece.

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

reflective

sad

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

It was a little slow to start out and I was not sure what I thought about it. As Asher grew up, his struggle to be an artist in his highly religious and unappreciative world became more real to me. I appreciated the story because I could relate to Asher's struggle with, but ultimate desire to remain true to, his parents and his religious community. It made me think about what I expect of my children and wanting to make the expectations I have for them a positive force in their lives.

one of the most misinformed books about Jewish people I've ever read. The fact its taught in schools is concerning

emotional

reflective

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

emotional

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

I finished reading My Name is Asher Lev for the second time yesterday. My experience reading it now was much richer and intimate than it was in 2007 when a creative writing teacher at BYU tried to generate a conversation around the tensions one might find as a writer and a Mormon. The conversation never really left the ground, but I did remember loving the book, so I decided to take it up again. This review looks at my reading from a personal lens of a Mormon and aspiring writer.

Maybe it is just where I am at in life right now, but this book really hit something for me. I loved learning more about his beautiful Jewish culture in Brooklyn. I realized that so much of it was similar to how Mormon culture works growing up in Utah and the tensions one might experience. The Rebbe figure is similar to how the bishop or the prophet is viewed in Mormonism. The tight-knit community that lives uniquely and apart from the world is also similar to Mormonism. World-wide service and humanitarian work and this sense of “our people,” regardless of nationality with other Mormons, again, hits very close to home. Active Mormons in the church are frequently called and asked to serve in the church in ways that sounded familiar to how Asher’s father was asked to serve. Asher was frustrated that his father was always gone. But his mother constantly reminded him that it was “for the Rebbe.” I have heard something similar in my own society, where all laymen and laywomen are asked to serve in the church in some capacity. I am sure many people feel the way Asher did when he expressed that his father “seemed more connected to the Jews of Russia than to the Jews of our own street” (55). I also understand something of the hate and deep misunderstanding he describes for his people, albeit, on a smaller level. I also feel like I understand the conversation Asher has with Anna very well:

““Are you very religious?”

“I’m an observant Jew.”

“What does that mean, specifically?”

I did not know what to say…..

“Asher Lev…Asher Lev…you are entering the wrong world…this world will destroy you. Art is not for people who want to make the world holy” (209-210).”

In addition, I think I understand the tension Asher Lev feels between his religious loyalties and his passions. “The world is not a pretty place,” the book reminds us. Yet, Asher feels drawn to depict it as he sees it. This is seen when he tells his mother “I don’t want to draw pretty drawings…I don’t like the world, Mama. It’s not pretty. I won’t draw it pretty” (28). Asher wants to “draw the light and the dark” (35). His honesty ultimately hurts people to the point where he (at least, his society) does not believe he can keep up the hybrid life of a Jewish artist. While I have never had anything that extreme happen to me, I feel like it is not hard to imagine what that would look like. I relate so well when Asher, talking about Yudel Krinsky’s experience in Siberia, says:

“I could feel the cold darkness moving slowly inside me. I could feel our darkness. It seemed to me then that we were brothers, he and I, that we both knew lands of ice and darkness. His had been in the past; mine was in the present. His had been outside himself; mine was within me” (41).

Like Asher, when I want to, I can see the world the way he does. I too have wondered if it is a good idea to act on it. (Jacob Kahn was right…who was “a great artist who was happy?” (224). To what cost? Is it worth it “to give in to a gift?” Perhaps it is wiser to heed the advice Asher was given: “one does with a life what is precious not only to one’s own self but to one’s own people” (133). What would Asher say by the end of the book? Would he agree with Jacob Kahn that he had “a responsibility,” not to Jews, but “to one and to nothing, except to yourself and to the truth as you see it”….and to “use guilt to make better art” (218)?

Is this journey “an unknowing act of atonement” that needs to be taken (324)?

Maybe it is just where I am at in life right now, but this book really hit something for me. I loved learning more about his beautiful Jewish culture in Brooklyn. I realized that so much of it was similar to how Mormon culture works growing up in Utah and the tensions one might experience. The Rebbe figure is similar to how the bishop or the prophet is viewed in Mormonism. The tight-knit community that lives uniquely and apart from the world is also similar to Mormonism. World-wide service and humanitarian work and this sense of “our people,” regardless of nationality with other Mormons, again, hits very close to home. Active Mormons in the church are frequently called and asked to serve in the church in ways that sounded familiar to how Asher’s father was asked to serve. Asher was frustrated that his father was always gone. But his mother constantly reminded him that it was “for the Rebbe.” I have heard something similar in my own society, where all laymen and laywomen are asked to serve in the church in some capacity. I am sure many people feel the way Asher did when he expressed that his father “seemed more connected to the Jews of Russia than to the Jews of our own street” (55). I also understand something of the hate and deep misunderstanding he describes for his people, albeit, on a smaller level. I also feel like I understand the conversation Asher has with Anna very well:

““Are you very religious?”

“I’m an observant Jew.”

“What does that mean, specifically?”

I did not know what to say…..

“Asher Lev…Asher Lev…you are entering the wrong world…this world will destroy you. Art is not for people who want to make the world holy” (209-210).”

In addition, I think I understand the tension Asher Lev feels between his religious loyalties and his passions. “The world is not a pretty place,” the book reminds us. Yet, Asher feels drawn to depict it as he sees it. This is seen when he tells his mother “I don’t want to draw pretty drawings…I don’t like the world, Mama. It’s not pretty. I won’t draw it pretty” (28). Asher wants to “draw the light and the dark” (35). His honesty ultimately hurts people to the point where he (at least, his society) does not believe he can keep up the hybrid life of a Jewish artist. While I have never had anything that extreme happen to me, I feel like it is not hard to imagine what that would look like. I relate so well when Asher, talking about Yudel Krinsky’s experience in Siberia, says:

“I could feel the cold darkness moving slowly inside me. I could feel our darkness. It seemed to me then that we were brothers, he and I, that we both knew lands of ice and darkness. His had been in the past; mine was in the present. His had been outside himself; mine was within me” (41).

Like Asher, when I want to, I can see the world the way he does. I too have wondered if it is a good idea to act on it. (Jacob Kahn was right…who was “a great artist who was happy?” (224). To what cost? Is it worth it “to give in to a gift?” Perhaps it is wiser to heed the advice Asher was given: “one does with a life what is precious not only to one’s own self but to one’s own people” (133). What would Asher say by the end of the book? Would he agree with Jacob Kahn that he had “a responsibility,” not to Jews, but “to one and to nothing, except to yourself and to the truth as you see it”….and to “use guilt to make better art” (218)?

Is this journey “an unknowing act of atonement” that needs to be taken (324)?