Take a photo of a barcode or cover

informative

medium-paced

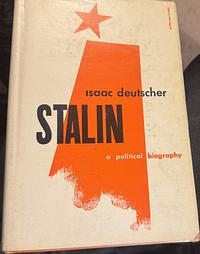

Monster devouring its own children: political biographies are inevitably biased by the author’s own beliefs - an unavoidable truism, but Isaac Deutscher was at least fairly self-aware and had the benefit of living through the era. This is an infuriating book but equally unputdownable not because one needs to know how it ends but because of the cult surrounding Jughashvili. Written by a lifelong communist - albeit a Trotskyite rather than a Stalinist - it can claim some objectivity and is probably the best we are going to get given the divisive subject matter.

Stalin was the least of the triumvirate that drove the Russian revolution: a poor Georgian peasant who was intelligent but uneducated, he lacked Lenin’s strategic mind and Trotsky’s intellect which left him with an entire potato harvest on his shoulder and a huge amount of “unscrupulous rancour and spite” demonstrated again and again through the purges, murder of opponents abroad (not an original idea of Putin’s, then), his treatment of Poland in the war or even the eruption of queeny fits against his rivals - Trotsky, “a poseur...with fake muscles.”

Deutscher’s balanced view is that Stalin‘s remarkable will drove him to feats way beyond the capacity of most people of his intellectual abilities - when he met Russia she was turning the fields with a wooden plough; when he left her she was dipping uranium rods into cooling ponds is how he sums up the remarkable transformation in 30 years. An agrarian, illiterate and unmechanised society had become industrial, technological, educated. For a poor boy from the mountains, resentfully educated at a third rate seminary it was a remarkable transformation to lead, yet there was “a baffling disproportion between the magnitude of the second revolution and its maker.” Much as this sounds like the bitter defeat of an opponent, Deutscher nevertheless makes the case that Stalin was a lesser man than Lenin, who had created and led the revolution, or Trotsky who saw the danger from Hitler whilst Stalin enabled him.

More than that, it was the terrible cost of everything he did, the thousands of opponents who died in the Gulags or by firing squad, the millions who starved in the botched bureaucracy of collectivisation, the sclerotic nightmare of a country where every thought, word and deed had to be approved by the Leader. His judgement was also far from the wise, all-seeing father of the nation despite the cult of Stalin’s projection of this as his character; see for instance the tale of the Polish American Catholic priest called Orlemanski from Springfield, Massachusetts, who tried to engage Stalin in commune with the Holy Father (as is the way of these things, the dictator went off the idea pretty quickly and the Pope defrocked the unfortunate priest). The echoes here of Rasputin make one think that poor Russia has gone from autocracy to oligarchy to kleptocracy with barely a break.

The first edition was written during Stalin’s lifetime - this later version contains an additional chapter which would have brought it up to date in the early 60s when Bay of Pigs paranoia was at its height. Its age means there is the stylistic datedness (he is fond of short tabloidesque sentences à la Alan Taylor which actually slow the pace, as well as an over-burdening use of statistics) and Deutscher’s of-its-time unwillingness to consider the personal as political was very much the then academic vogue. He talks of the Stalianist era as a monster devouring its own children which is an interesting turn of phrase considering Stalin drove his second wife to suicide and his children became alcoholics or defectors, and this deserves its own treatise. Even with these considerations of hindsight, which do make it a challenge, it’s a thorough, compelling and probably as comprehensive biography as we are likely to get. The battered Pelican I have fell into my bag (oops) just as I was leaving Chatham House school in 1985. I feel as though now I’ve repaid my debt.

Stalin was the least of the triumvirate that drove the Russian revolution: a poor Georgian peasant who was intelligent but uneducated, he lacked Lenin’s strategic mind and Trotsky’s intellect which left him with an entire potato harvest on his shoulder and a huge amount of “unscrupulous rancour and spite” demonstrated again and again through the purges, murder of opponents abroad (not an original idea of Putin’s, then), his treatment of Poland in the war or even the eruption of queeny fits against his rivals - Trotsky, “a poseur...with fake muscles.”

Deutscher’s balanced view is that Stalin‘s remarkable will drove him to feats way beyond the capacity of most people of his intellectual abilities - when he met Russia she was turning the fields with a wooden plough; when he left her she was dipping uranium rods into cooling ponds is how he sums up the remarkable transformation in 30 years. An agrarian, illiterate and unmechanised society had become industrial, technological, educated. For a poor boy from the mountains, resentfully educated at a third rate seminary it was a remarkable transformation to lead, yet there was “a baffling disproportion between the magnitude of the second revolution and its maker.” Much as this sounds like the bitter defeat of an opponent, Deutscher nevertheless makes the case that Stalin was a lesser man than Lenin, who had created and led the revolution, or Trotsky who saw the danger from Hitler whilst Stalin enabled him.

More than that, it was the terrible cost of everything he did, the thousands of opponents who died in the Gulags or by firing squad, the millions who starved in the botched bureaucracy of collectivisation, the sclerotic nightmare of a country where every thought, word and deed had to be approved by the Leader. His judgement was also far from the wise, all-seeing father of the nation despite the cult of Stalin’s projection of this as his character; see for instance the tale of the Polish American Catholic priest called Orlemanski from Springfield, Massachusetts, who tried to engage Stalin in commune with the Holy Father (as is the way of these things, the dictator went off the idea pretty quickly and the Pope defrocked the unfortunate priest). The echoes here of Rasputin make one think that poor Russia has gone from autocracy to oligarchy to kleptocracy with barely a break.

The first edition was written during Stalin’s lifetime - this later version contains an additional chapter which would have brought it up to date in the early 60s when Bay of Pigs paranoia was at its height. Its age means there is the stylistic datedness (he is fond of short tabloidesque sentences à la Alan Taylor which actually slow the pace, as well as an over-burdening use of statistics) and Deutscher’s of-its-time unwillingness to consider the personal as political was very much the then academic vogue. He talks of the Stalianist era as a monster devouring its own children which is an interesting turn of phrase considering Stalin drove his second wife to suicide and his children became alcoholics or defectors, and this deserves its own treatise. Even with these considerations of hindsight, which do make it a challenge, it’s a thorough, compelling and probably as comprehensive biography as we are likely to get. The battered Pelican I have fell into my bag (oops) just as I was leaving Chatham House school in 1985. I feel as though now I’ve repaid my debt.

This could have been a turgid mess, but Deutscher keeps it interesting and relevant. A good book for anyone interested in Russian history.

slow-paced

Has some inaccuracies as discussed by Robert Tucker and others, partly just not acknowledging historian disagreement on certain areas, e.g. Stalin's parents. In his defence this is partly due to lack of resources (not sure why you'd write a Stalin biography in the 40s). Also think this wouldn't be great for people new to the area, Deutscher presumes some basic knowledge and doesn't explain events like the Kirov murder in detail. Mostly I just really dislike his writing style, I think it's unnecessarily convoluted and takes the interesting parts out of the subject. I also don't appreciate his random decision near the end of the book to just add a lot of french phrases. Even when they were cognates and easily understandable it was a bit odd and looked like he was just trying to make himself smart. Also his decision to make inferences on historical figures felt unnecessary ('Trosky must've been feeling.... At this point') and could've been ommitted, or at least not taken up multiple paragraphs/pages at a time. I also dislike his running metaphors. You made the point in the first sentence, don't continue it for ten pages. I'm not sure what I expected on a book that's so regularly cited for its issues though. Was worth the read for more knowledge on those references to it I guess but just not my favourite.

informative

slow-paced

At university I studied Quantum Chemistry but was friends with a lot of people studying Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) and often was mistaken for being either someone studying PPE or Theology LOL

This book was part of my wider reading on history and politics that I did when I was an undergraduate and it earned me the nickname of "Stalin" amongst a few of the people in the year below me - I think it was because I read it in the Junior Common Room and in the bar at college - it was for one term the "book in my bag".

Deutscher possibly because he didn't like Stalin does a good deal of research on him and the early Soviet Union. It is not a hatchet-job in the way it could have been but it was not a hagiography. It is how I like my political biographies.

This book was part of my wider reading on history and politics that I did when I was an undergraduate and it earned me the nickname of "Stalin" amongst a few of the people in the year below me - I think it was because I read it in the Junior Common Room and in the bar at college - it was for one term the "book in my bag".

Deutscher possibly because he didn't like Stalin does a good deal of research on him and the early Soviet Union. It is not a hatchet-job in the way it could have been but it was not a hagiography. It is how I like my political biographies.