Take a photo of a barcode or cover

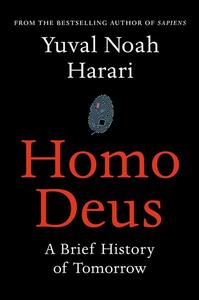

Good book, the main difference between Homo Sapiens and Homo Deus is the perspective, while the first is based on past it relies heavily on facts, the second one tries to be more predictive in our options for the future, and uses a lot of hypothetical guesses. The book analyzes different religions (money, Christianism, communism, liberalism...) from a philosophical perspective. Homo Deus also grabs some concepts from the last book, mainly the concept of mythological entities.

Great book for anyone who already thought about what humans will revere after money.

Great book for anyone who already thought about what humans will revere after money.

I thought it was even better than Sapiens... some of these ideas will stick with me for a long time. Religion -> Humanism ->Dataism

The first book by Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari, "Sapiens", was a bold, brash, and mesmerizing history of humankind. His follow-up "Homo Deus" is a companion piece; it expands some of the concepts of its predecessor while speculating on the future of our species that was hinted at in the final chapter of "Sapiens". Based on the current aspirations of the human race, and barring any catastrophe caused by climate change or otherwise, where will humans go from here?

The author avers that the reason for humans' power over the planet is not due to higher intelligence or opposable thumbs, but our ability to coordinate huge numbers of individuals through "intersubjective realities": shared fictions like money and nations. Over millennia, our sources of ethics and meaning have shifted from various holy scriptures to our own inner selves – what Harari calls liberal humanism, or liberalism (used here in its non-American definition). As scientific research continue to reveal that each of is less of an individual and more of set of complicated algorithms, and as technology becomes ever more adept at replicating and even surpassing these biological algorithms, will a majority of human beings become useless? This is what "Homo Deus" ponders in its final third.

Harari has a way of making gleefully provocative statements about big subjects, in lucid and readable language. Thus, this is a book bound to piss a lot of people off, and/or spur intoxicated debates. I had difficulties finding fault with most of his observations, though, and I was fairly shook by the time I was done – everything around me and on TV felt like the last gasp of an old epoch of the species. "Homo Deus" makes it clear that technology is not deterministic, and we can never properly predict the paths it will take. But what the book makes so vivid is how fleeting and flimsy our sense of self-importance really is.

The author avers that the reason for humans' power over the planet is not due to higher intelligence or opposable thumbs, but our ability to coordinate huge numbers of individuals through "intersubjective realities": shared fictions like money and nations. Over millennia, our sources of ethics and meaning have shifted from various holy scriptures to our own inner selves – what Harari calls liberal humanism, or liberalism (used here in its non-American definition). As scientific research continue to reveal that each of is less of an individual and more of set of complicated algorithms, and as technology becomes ever more adept at replicating and even surpassing these biological algorithms, will a majority of human beings become useless? This is what "Homo Deus" ponders in its final third.

Harari has a way of making gleefully provocative statements about big subjects, in lucid and readable language. Thus, this is a book bound to piss a lot of people off, and/or spur intoxicated debates. I had difficulties finding fault with most of his observations, though, and I was fairly shook by the time I was done – everything around me and on TV felt like the last gasp of an old epoch of the species. "Homo Deus" makes it clear that technology is not deterministic, and we can never properly predict the paths it will take. But what the book makes so vivid is how fleeting and flimsy our sense of self-importance really is.

informative

inspiring

reflective

sad

tense

medium-paced

A feeling of dread will come over you at different points while reading "Homo Deus", a follow-up novel to Yuval Noah Harari's highly successful "Homo Sapiens". That feeling of dread may even develop into fear if you believe that Liberalism and Democracy are philosophies that produce the best and fairest modern societies.

Normally I actively avoid works that attempt to explain what the future will be like but Yuval Noah Harari has produced another thought provoking piece of work with the aim to merely outline the potential options ahead for society on decade time scales. His focus is mostly on the role of data in modern life and some of the potential social and political implications as data begins to play an even greater role in our lives.

While the first third of the book is pretty much a recap of "Homo Sapiens", the second third is a phenomenal piece of work on where society is heading with the integration of data into nearly all aspects of life, but particularly the strange bed-fellows of biology and computer science. For example, what will happen to democracy when an algorithm knows with almost certainty how you are going to vote? What does it mean for love if a person torn between two lovers can ask an algorithm to tell them who they really love? These are just some of the questions raised in "Homo Deus". Unfortunately, I do find the last third of the book falls apart, as Harari tries to extend himself into understanding more long term social evolutions. In particular, his outline of the new religions of Dataism and Homo Deus are very preliminary and will likely be outdated within the decade, if not sooner.

While I do not always agree with his philosophy, Harari has again produced a novel that will make you critically think about your life and where society is heading.

Normally I actively avoid works that attempt to explain what the future will be like but Yuval Noah Harari has produced another thought provoking piece of work with the aim to merely outline the potential options ahead for society on decade time scales. His focus is mostly on the role of data in modern life and some of the potential social and political implications as data begins to play an even greater role in our lives.

While the first third of the book is pretty much a recap of "Homo Sapiens", the second third is a phenomenal piece of work on where society is heading with the integration of data into nearly all aspects of life, but particularly the strange bed-fellows of biology and computer science. For example, what will happen to democracy when an algorithm knows with almost certainty how you are going to vote? What does it mean for love if a person torn between two lovers can ask an algorithm to tell them who they really love? These are just some of the questions raised in "Homo Deus". Unfortunately, I do find the last third of the book falls apart, as Harari tries to extend himself into understanding more long term social evolutions. In particular, his outline of the new religions of Dataism and Homo Deus are very preliminary and will likely be outdated within the decade, if not sooner.

While I do not always agree with his philosophy, Harari has again produced a novel that will make you critically think about your life and where society is heading.

Homo Deus is an example of what might be called speculative history. Starting with the premise that the hitherto defining concerns for humanity - war, famine and pestilence - have in effect been (or will soon be) defeated, Harari poses the question: what comes next?

His answer is the extension of life (perhaps to immortality), the ubiquity of happiness, and the achievement of divinity. These lofty ambitions are a bit much to take on face value, but Harari spends some time justifying them at the beginning of his book. Like most speculative writing, the author needs to provide enough context for the reader to suspend disbelief. But Harari does not quite make it, and what follows fails as a consequence.

Homo Deus takes several unexpected, fascinating turns, exploring the subject of the relationship between humans and animals, or the of the rise of humanism and what it has in common with religion. It explores post-humanist potentials for our future, including human enhancement to 'super humans' and the potential rise of dataism as a new reigning principle for human society. While these explorations have some interesting aspects in their own right, they stand on tenuous ground.

For instance, much of the book pivots on a single core idea: biological things are algorithms. This statement is asserted a lot, and the reader is assured from time to time that the life sciences have accepted this, whether we agree with it or not.

Though Harari himself suggests things might not be so simple, he skates over the argument to begin with, without thoroughly interrogating it. He then assumes the argument that humans are algorithms throughout the rest of the book, and it becomes central to many of the later ideas.

In the end, he never returns to his original three proposals; they're left as raised hypotheses that are not given grounding in his own work. In other words, it lacks a sense of purpose and direction, which makes it very difficult for the reader to ever suspend their disbelief and take the speculations very serious.

In short, the history parts are interesting, the speculative parts unbelievable. This shouldn't be too surprising - Harari is a historian.

His answer is the extension of life (perhaps to immortality), the ubiquity of happiness, and the achievement of divinity. These lofty ambitions are a bit much to take on face value, but Harari spends some time justifying them at the beginning of his book. Like most speculative writing, the author needs to provide enough context for the reader to suspend disbelief. But Harari does not quite make it, and what follows fails as a consequence.

Homo Deus takes several unexpected, fascinating turns, exploring the subject of the relationship between humans and animals, or the of the rise of humanism and what it has in common with religion. It explores post-humanist potentials for our future, including human enhancement to 'super humans' and the potential rise of dataism as a new reigning principle for human society. While these explorations have some interesting aspects in their own right, they stand on tenuous ground.

For instance, much of the book pivots on a single core idea: biological things are algorithms. This statement is asserted a lot, and the reader is assured from time to time that the life sciences have accepted this, whether we agree with it or not.

Though Harari himself suggests things might not be so simple, he skates over the argument to begin with, without thoroughly interrogating it. He then assumes the argument that humans are algorithms throughout the rest of the book, and it becomes central to many of the later ideas.

In the end, he never returns to his original three proposals; they're left as raised hypotheses that are not given grounding in his own work. In other words, it lacks a sense of purpose and direction, which makes it very difficult for the reader to ever suspend their disbelief and take the speculations very serious.

In short, the history parts are interesting, the speculative parts unbelievable. This shouldn't be too surprising - Harari is a historian.

informative

fast-paced

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

informative

inspiring

medium-paced