Take a photo of a barcode or cover

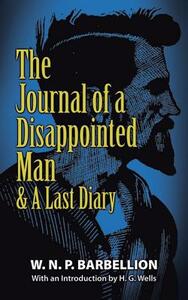

For most people, middle-age is the period in life when they first begin to feel the presence of their fragile mortality. As such, there is something unique, something terrible in fact, about a person in their twenties experiencing that same crisis due to a debilitating illness. Barbellion's journal begins when he is 13 and contains, as you might predict, a series of careless references to trivial matters which require diary entries of brevity and pure description. He is a boy fascinated by the natural world, by insects and animals, by the rapid arrival of knowledge and wonder. It's only in his late teens when the diary becomes something else, when Barbellion begins to notice that his body is showing strange signs of numbness and weakness. He knows something is wrong but doesn't know what, and only towards his last few years does he finally get a name for his illness: multiple sclerosis.

I generally don't read non-fiction books these days (and certainly not life writings) but this book (by title alone) had something that appealed to me. At this point I will reference the wonderful 'Book of Disquiet' by Pessoa, another diary but one which is more overtly creative and literary in its intentions. While that book has no chronology and feels like the random (and very beautiful) exploration of a man's private thoughts, this book (though also with a literary flourish to the prose) is a more coherent insight into the slow deterioration of a man's body and soul. As the journal goes on, the entries become longer and more reflective; as the illness progresses, Barbellion ceases to simply detail his day-to-day existence and instead begins to contemplate existence, to disclose more and more of himself, his inner turmoil, his fears and regrets, but more so (and very honestly), his (self-confessed) egotistical belief that he could have contributed something more had he lived longer.

There are some wonderful insights throughout the journal, entries which are exquisite, sad, angry and poignant. Towards the end, he endeavours to get the journal published and even succeeds, living long enough to hold a copy of the book (with an introduction by H.G Wells) in his hand. His original journal (the one he saw published) ended in 1917 and closed with the (false) words 'Barbellion died on December 31.' In realty he lived another two years and those last diary entries are also included here. The fact that he ended the original journal with a lie was based on the genuine belief that he would not live to see it published (or further material added). None the less, I interpret this as evidence that a certain creative license was indeed being enjoyed by Barbellion. That isn't to say the journal isn't a true account, but merely that he, like Pessoa, had a flair for the poetic and romantic.

The book was so easy to read, so wonderfully written. It offers so many amazing thoughts and phrases, the prose being truly magnificent, the subject matter, significant and powerful. I especially enjoyed the moment when he is talking to his wife about his impending death.

"[she] says widows' weeds have been so vulgarised by the war widows that she won't go into deep mourning. 'But you'll wear just one weed or two for me?' I plead, and then we laugh. She has promised me that should a suitable chance arise, she will marry again. Personally, I wish I could place my hand on the young fellow at once, so as to put him through his paces -- show him where the water main runs and where the gas meter is, and so on."

The man and his work deserves far more recognition. Superb!

I generally don't read non-fiction books these days (and certainly not life writings) but this book (by title alone) had something that appealed to me. At this point I will reference the wonderful 'Book of Disquiet' by Pessoa, another diary but one which is more overtly creative and literary in its intentions. While that book has no chronology and feels like the random (and very beautiful) exploration of a man's private thoughts, this book (though also with a literary flourish to the prose) is a more coherent insight into the slow deterioration of a man's body and soul. As the journal goes on, the entries become longer and more reflective; as the illness progresses, Barbellion ceases to simply detail his day-to-day existence and instead begins to contemplate existence, to disclose more and more of himself, his inner turmoil, his fears and regrets, but more so (and very honestly), his (self-confessed) egotistical belief that he could have contributed something more had he lived longer.

There are some wonderful insights throughout the journal, entries which are exquisite, sad, angry and poignant. Towards the end, he endeavours to get the journal published and even succeeds, living long enough to hold a copy of the book (with an introduction by H.G Wells) in his hand. His original journal (the one he saw published) ended in 1917 and closed with the (false) words 'Barbellion died on December 31.' In realty he lived another two years and those last diary entries are also included here. The fact that he ended the original journal with a lie was based on the genuine belief that he would not live to see it published (or further material added). None the less, I interpret this as evidence that a certain creative license was indeed being enjoyed by Barbellion. That isn't to say the journal isn't a true account, but merely that he, like Pessoa, had a flair for the poetic and romantic.

The book was so easy to read, so wonderfully written. It offers so many amazing thoughts and phrases, the prose being truly magnificent, the subject matter, significant and powerful. I especially enjoyed the moment when he is talking to his wife about his impending death.

"[she] says widows' weeds have been so vulgarised by the war widows that she won't go into deep mourning. 'But you'll wear just one weed or two for me?' I plead, and then we laugh. She has promised me that should a suitable chance arise, she will marry again. Personally, I wish I could place my hand on the young fellow at once, so as to put him through his paces -- show him where the water main runs and where the gas meter is, and so on."

The man and his work deserves far more recognition. Superb!

Really closer to 3.5 stars, the first half was 3 stars and the second half was 4 stars (his journal got better as he aged and as he started to grapple with his impending death more). Rounding to 4 stars because of recency bias.