Take a photo of a barcode or cover

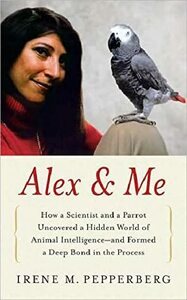

Alex, if not Irene Pepperberg, is a household name. I vaguely remember in middle school watching the famous Alex videos and having all of my ideas about animal intelligence challenged. My dad eagerly tells of his experience meeting Irene Pepperberg (I'm sure I'll get an e-mail from him reminding me that he knows her personally after I publish this review), so they're both definitely household names in my life. Therefore, there is little attempt to familiarize the reader with the story of Alex or why he is important and the attempt that is made (a painfully long intro/eulogy) is unnecessary.

I was expecting the book to largely focus on the science of working with Alex and how Dr. Pepperberg formulated the work as she had and what she has concluded. Instead, Dr. Pepperberg makes the decision to really write a memoir, which turns out to be a fascinating look at how much being a scientist requires overcoming opposition and how favored one is by lucky coincidences. Most interesting, to me, at least, is Pepperberg's explorations of the setbacks she faces, especially as a female scientist, and the unconventional methods she turns to to get funding and faculty support. It is really very telling about the state of American science that as famous of a scientist as Pepperberg is, she still reverts to private funding and adjunct faculty positions.

I was expecting the book to largely focus on the science of working with Alex and how Dr. Pepperberg formulated the work as she had and what she has concluded. Instead, Dr. Pepperberg makes the decision to really write a memoir, which turns out to be a fascinating look at how much being a scientist requires overcoming opposition and how favored one is by lucky coincidences. Most interesting, to me, at least, is Pepperberg's explorations of the setbacks she faces, especially as a female scientist, and the unconventional methods she turns to to get funding and faculty support. It is really very telling about the state of American science that as famous of a scientist as Pepperberg is, she still reverts to private funding and adjunct faculty positions.

emotional

funny

informative

inspiring

fast-paced

A fascinating exploration of animal intelligence and the roots of language and learning. My neighbors were telling me about a friend of theirs who has an African grey parrot that plays video games. It spurred me to pull this book off of Mt TBR. Dr. Pepperberg is a driven woman who went from a PhD in theoretical chemistry (which I had not heard of before) to doing biological research into animal intelligence. She selects as her partner an African grey named Alex and begins to break all the rules about the what non-human animals can do. He learns labels for objects and colors and numbers and even grasps relative quantity despite not having been taughg to count or the order of numbers. He was engaged in experiments regarding optical illusions and visual perception at the time of his sudden death. I got a kick out of Alex's sense of humor (although Pepperberg is a dedicated scientist and doesn't use that term) and his crsativity -- "banerry." It makes perfect sense to me that birds like Alex are intelligent and have emotions, so I appreciated the chapter at the end which explained why science requires proof of that.

I'm personally not a bird person, but I started listening to the audiobook version of this book mainly because it was available from my library, but also because a co-worker has a 2-year-old African grey parrot named Gracie. After hearing tales from him about his bird child that sound very similar to tales I tell of my 2-year-old human child, I thought this would be an interesting book to read.

Not more than a couple of hours after I finished reading this book about a famous African Grey Parrot who died at age 30 did I hear the fresh news of a bird named Horace who died after being in a friend's family for 45 years. That phrase really struck me ... a bird that had "been in the family for 45 years". Having an animal is always a big responsibility, but I cannot imagine having a bird that would outlive me and have to be passed along within the family. Losing such a bird would be like losing a family member in many ways.

A few weeks ago, we had to put our dog down. It was hard enough to do so with an animal that couldn't talk. We hoped she couldn't understand what we were saying. But if she could talk and we knew that she could understand the decisions that we were making in front of her, I don't think the decision-making process would have been the same. If she had been a bird that could comprehend what we were saying and could say, "please don't put me to sleep," I think I would have been a complete basketcase for weeks rather than be able to get on with my life. It's sad but true that we as humans react differently to living beings based on their size, longevity, and ability to communicate with and understand us.

The author tells us about her childhood and how she rarely socialized with anyone (other than her pet birds) until she started school. She grew up in a family that was not very demonstrative with their affection. That type of childhood is very foreign to me, so I'm glad that she started the book explaining this. I can't even imagine what type of social issues someone would have starting school if they'd really never reacted with anyone outside their family (and barely with anyone within her family). This background very much explains why she originally embarked on this project with the idea that she was going to approach her research project with Alex the bird from a strictly clinical point of view. She wasn't going to let herself become emotionally attached to him. However, the 30 years that she spent with him seem to have created a change within her because she did become emotionally attached to him. And she did come to the conclusion that she needed to study the intelligence of birds within a social rather than a clinical setting.

I had a 2-fold reaction to this book:

1. How horrible it must have been to be a bird subjected to scientific experimentation for 30 years. How tedious to keep answering the same questions over and over about the names of objects, their color, and their size.

2. How wonderful that someone discovered how complex animal brains can be. And how great for this bird that he had someone to keep him from being bored day in and day out (if he was going to have to live in captivity).

I've also drawn some interesting conclusions as a result of reading it:

1. Birds are more fascinating and intelligent than I originally thought.

2. If a bird-sized brain can understand concepts like "none" and use phonics, then how much more intellectually advanced are the animals all around us who can't vocalize their thoughts?

3. Most people shouldn't own birds because most people cannot provide them with the time and attention that they need to not become bored.

3. I never want to own a bird. I didn't have any desire to own one before, and now I really know that I don't ever want a bird (especially one that can talk).

That said, since reading this, I've become more aware of the birds that frequent my yard. I noticed them before, but I didn't think of them in terms of personalities. Now I wonder how old they might be, what they're thinking, and what personalities they have. We have a new mockingbird in the yard that's been lately antagonizing the neighborhood porch kitty (that my 2-year-old named Cumin). Cumin's been dive-bombed on numerous occasions. And I have to wonder what's going through the mockingbird's head. With the mockingbird's ability for language-acquisition, it makes me think that his/her thought process must be a complex one indeed.

One thing that my co-worker has said about his African grey parrot is that living with Gracie is like living with a little alien. Even though she speaks English, the thought processes she has seem to be very foreign to ours. However, being around a talking bird is beyond just being around someone who has a different culture. The author of this book made a similar statement in her conclusion. So I think that I'm going to from now on see birds as little aliens that we live among. Thus, the fabled "little green alien" we've been waiting for is as close as your nearest tree or pet store.

Not more than a couple of hours after I finished reading this book about a famous African Grey Parrot who died at age 30 did I hear the fresh news of a bird named Horace who died after being in a friend's family for 45 years. That phrase really struck me ... a bird that had "been in the family for 45 years". Having an animal is always a big responsibility, but I cannot imagine having a bird that would outlive me and have to be passed along within the family. Losing such a bird would be like losing a family member in many ways.

A few weeks ago, we had to put our dog down. It was hard enough to do so with an animal that couldn't talk. We hoped she couldn't understand what we were saying. But if she could talk and we knew that she could understand the decisions that we were making in front of her, I don't think the decision-making process would have been the same. If she had been a bird that could comprehend what we were saying and could say, "please don't put me to sleep," I think I would have been a complete basketcase for weeks rather than be able to get on with my life. It's sad but true that we as humans react differently to living beings based on their size, longevity, and ability to communicate with and understand us.

The author tells us about her childhood and how she rarely socialized with anyone (other than her pet birds) until she started school. She grew up in a family that was not very demonstrative with their affection. That type of childhood is very foreign to me, so I'm glad that she started the book explaining this. I can't even imagine what type of social issues someone would have starting school if they'd really never reacted with anyone outside their family (and barely with anyone within her family). This background very much explains why she originally embarked on this project with the idea that she was going to approach her research project with Alex the bird from a strictly clinical point of view. She wasn't going to let herself become emotionally attached to him. However, the 30 years that she spent with him seem to have created a change within her because she did become emotionally attached to him. And she did come to the conclusion that she needed to study the intelligence of birds within a social rather than a clinical setting.

I had a 2-fold reaction to this book:

1. How horrible it must have been to be a bird subjected to scientific experimentation for 30 years. How tedious to keep answering the same questions over and over about the names of objects, their color, and their size.

2. How wonderful that someone discovered how complex animal brains can be. And how great for this bird that he had someone to keep him from being bored day in and day out (if he was going to have to live in captivity).

I've also drawn some interesting conclusions as a result of reading it:

1. Birds are more fascinating and intelligent than I originally thought.

2. If a bird-sized brain can understand concepts like "none" and use phonics, then how much more intellectually advanced are the animals all around us who can't vocalize their thoughts?

3. Most people shouldn't own birds because most people cannot provide them with the time and attention that they need to not become bored.

3. I never want to own a bird. I didn't have any desire to own one before, and now I really know that I don't ever want a bird (especially one that can talk).

That said, since reading this, I've become more aware of the birds that frequent my yard. I noticed them before, but I didn't think of them in terms of personalities. Now I wonder how old they might be, what they're thinking, and what personalities they have. We have a new mockingbird in the yard that's been lately antagonizing the neighborhood porch kitty (that my 2-year-old named Cumin). Cumin's been dive-bombed on numerous occasions. And I have to wonder what's going through the mockingbird's head. With the mockingbird's ability for language-acquisition, it makes me think that his/her thought process must be a complex one indeed.

One thing that my co-worker has said about his African grey parrot is that living with Gracie is like living with a little alien. Even though she speaks English, the thought processes she has seem to be very foreign to ours. However, being around a talking bird is beyond just being around someone who has a different culture. The author of this book made a similar statement in her conclusion. So I think that I'm going to from now on see birds as little aliens that we live among. Thus, the fabled "little green alien" we've been waiting for is as close as your nearest tree or pet store.

A lay person's version of the scientific study of a parrot's thought, learning and speech process, as studied over thirty years by the author. Fascinating evidence of the brain development and communication abilities of non-human, non-mammalian species.

I obviously need to start reading more books about women scientists. I absolutely loved this.

I have always thought that animals know more than what we give them credit for, but this book was still an eye-opener for me. Parts had me laughing out loud. Great read, but the introduction was slow for me (I was unfamiliar with Alex and did not yet fully appreciate the descriptions of emotional outpouring she uses to begin the book). Highly recommend!

emotional

informative

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Graphic: Animal death

This is great as memoir and science until the last third of the last chapter, which goes a little woo and a lot simplistic about the global south and pre-colonial peoples in the Americas.

But overwhelmingly positive.

But overwhelmingly positive.