Scan barcode

frankie_s's review

5.0

I bought this from my local library sale trolley for 50 cents on the strength of the title alone (I lived in Penrith once) and wow what a book. Quick but also sometimes tedious, frustrating, exhilarating, recursive, focused on interiority in a way that plays with timelines, subjectivity, narration, and spatial orientation. I’ve never read anything like it but it feels as familiar as the inside of my own head while walking.

thirdcoast's review

Life is too short for this meandering to nowhere. Made it 3 pages in.

kaydee's review

4.0

This stream of consciousness, introspective novella really deserves to be read in one sitting.

Unfortunately I didn't have the luxury of time this week and could only read a few pages here and there which I think made it a more challenging read than it needed to be.

That said, I enjoyed this very original work, a walking meditation that blurs the lines between fiction, memoir and philosophy.

A thought provoking and insightful read.

Unfortunately I didn't have the luxury of time this week and could only read a few pages here and there which I think made it a more challenging read than it needed to be.

That said, I enjoyed this very original work, a walking meditation that blurs the lines between fiction, memoir and philosophy.

A thought provoking and insightful read.

wtb_michael's review against another edition

4.0

An original and intense novella - the action covers the distance of a walk from Glebe to Surry Hills, but the book covers the entire internal narrative of the central character, Jen Craig. You weave in and our of her memories - of conversations, friendships, family and childhood, while she negotiates the handful of blocks of her walk. Craig's thoughts spiral around the manuscript she's carrying - written by an old friend who has recently died - and it sparks off musings on creativity and ambition, on friendship, anorexia, self-perception and the ways in which we present ourselves to the world (and even to ourselves).

It's a challenging, breathless read - there are barely any paragraphs, with the text acting as the non-stop burble of thoughts in the narrator's head, jumping off each other and being interrupted by the world around her, but never really pausing for breath. It's an impressive, inventive feat of memoir/fiction, but I'm glad she kept the book short - you really need to read it in one sitting to stay immersed.

It's a challenging, breathless read - there are barely any paragraphs, with the text acting as the non-stop burble of thoughts in the narrator's head, jumping off each other and being interrupted by the world around her, but never really pausing for breath. It's an impressive, inventive feat of memoir/fiction, but I'm glad she kept the book short - you really need to read it in one sitting to stay immersed.

randomreader405a3's review

4.0

My review is now up at All the Novellas: http://allthenovellas.com/2015/08/23/5-panthers-and-the-museum-of-fire-by-jen-craig/

catdad77a45's review

3.0

2.5, rounded up.

Although this has been called 'stream-of consciousness' and auto-fiction, neither term is quite accurate, though I'd be hard pressed explaining exactly what it IS. It tells a quite simple story in the most loquacious, roundabout way possible - and unfortunately, in that respect, it reminded me of two books I absolutely loathed: [b:Milkman|36047860|Milkman|Anna Burns|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1526985855l/36047860._SY75_.jpg|57622946] and [b:Solar Bones|29773751|Solar Bones|Mike McCormack|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1459779562l/29773751._SX50_.jpg|50139645] - but oddly, also of one I adored: [b:Ducks, Newburyport|43412920|Ducks, Newburyport|Lucy Ellmann|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1546225252l/43412920._SX50_.jpg|67454703] (maybe just the late appearing panthers of the title, which evoked the mountain lion in Ellmann's tome).

My main problem is that, in minuscule font extremely difficult for my old eyes to make out, and in paragraphs that often went on (and on and on) for literally 5 or 6 pages - and single sentences often stretched for a page or more, the narrator (also called Jen Craig, hence the auto-fictional element) details the minutiae of a trip from her Sydney home to a café close by, where she is to return a manuscript written by a recently deceased frenemy to the sister of such. That's pretty much IT for plot, but in the 130 pages she takes to get there, she constantly returns to the same three or four topics occupying her thoughts, none of which are in the least bit interesting (her relationship to her seemingly only OTHER friend, Raf; her one-time conversion to religion, that didn't take; her struggles with anorexia [which leads to the ONE chuckle in the book, about her sharing the name of a diet company]; her depressing, dying father and his inability to write, which matches her own frustrations in that regard).

This style of writing, with the long run-on thoughts/sentences that I find extremely difficult to parse and make sense of, just isn't for me, but there were a (very) few sequences that I could decipher, and found mildly entertaining, in particular, a rant about how often books use large font and copious amounts of white space so that they'll SEEM much longer than they are ... would that she had followed that same path, which would at least have eased the eye strain. And the final few pages, in which the narrator achieves something of a breakthrough in her stalled writing, seemed a small victory, making what came before not a total waste.

Although this has been called 'stream-of consciousness' and auto-fiction, neither term is quite accurate, though I'd be hard pressed explaining exactly what it IS. It tells a quite simple story in the most loquacious, roundabout way possible - and unfortunately, in that respect, it reminded me of two books I absolutely loathed: [b:Milkman|36047860|Milkman|Anna Burns|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1526985855l/36047860._SY75_.jpg|57622946] and [b:Solar Bones|29773751|Solar Bones|Mike McCormack|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1459779562l/29773751._SX50_.jpg|50139645] - but oddly, also of one I adored: [b:Ducks, Newburyport|43412920|Ducks, Newburyport|Lucy Ellmann|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1546225252l/43412920._SX50_.jpg|67454703] (maybe just the late appearing panthers of the title, which evoked the mountain lion in Ellmann's tome).

My main problem is that, in minuscule font extremely difficult for my old eyes to make out, and in paragraphs that often went on (and on and on) for literally 5 or 6 pages - and single sentences often stretched for a page or more, the narrator (also called Jen Craig, hence the auto-fictional element) details the minutiae of a trip from her Sydney home to a café close by, where she is to return a manuscript written by a recently deceased frenemy to the sister of such. That's pretty much IT for plot, but in the 130 pages she takes to get there, she constantly returns to the same three or four topics occupying her thoughts, none of which are in the least bit interesting (her relationship to her seemingly only OTHER friend, Raf; her one-time conversion to religion, that didn't take; her struggles with anorexia [which leads to the ONE chuckle in the book, about her sharing the name of a diet company]; her depressing, dying father and his inability to write, which matches her own frustrations in that regard).

This style of writing, with the long run-on thoughts/sentences that I find extremely difficult to parse and make sense of, just isn't for me, but there were a (very) few sequences that I could decipher, and found mildly entertaining, in particular, a rant about how often books use large font and copious amounts of white space so that they'll SEEM much longer than they are ... would that she had followed that same path, which would at least have eased the eye strain. And the final few pages, in which the narrator achieves something of a breakthrough in her stalled writing, seemed a small victory, making what came before not a total waste.

arirang's review

5.0

...the whole of the reading seemed to be just the prelude to a reading; it pulled you along from one sentence to the next, one paragraph to the next, and you held on for some reason, never doubting for an instant that the real part of the story would be about to begin; and even when you knew, later on, when it was evidently too late, that there was no real part – when you watched yourself holding on to your role in the reading like an idiotic fool, holding on for the real part to begin when all the time there was never a real part, all the time there was nothing but the reading of the manuscript one word after another, the words being everything, the storyline nothing – you continued to read, I should have told Raf last night, although I was still jet-lagged, if I could call it that, from the experience of reading and writing.

This wonderful novella came to my attention via a tweet from Martin Shaw @booksdesk:

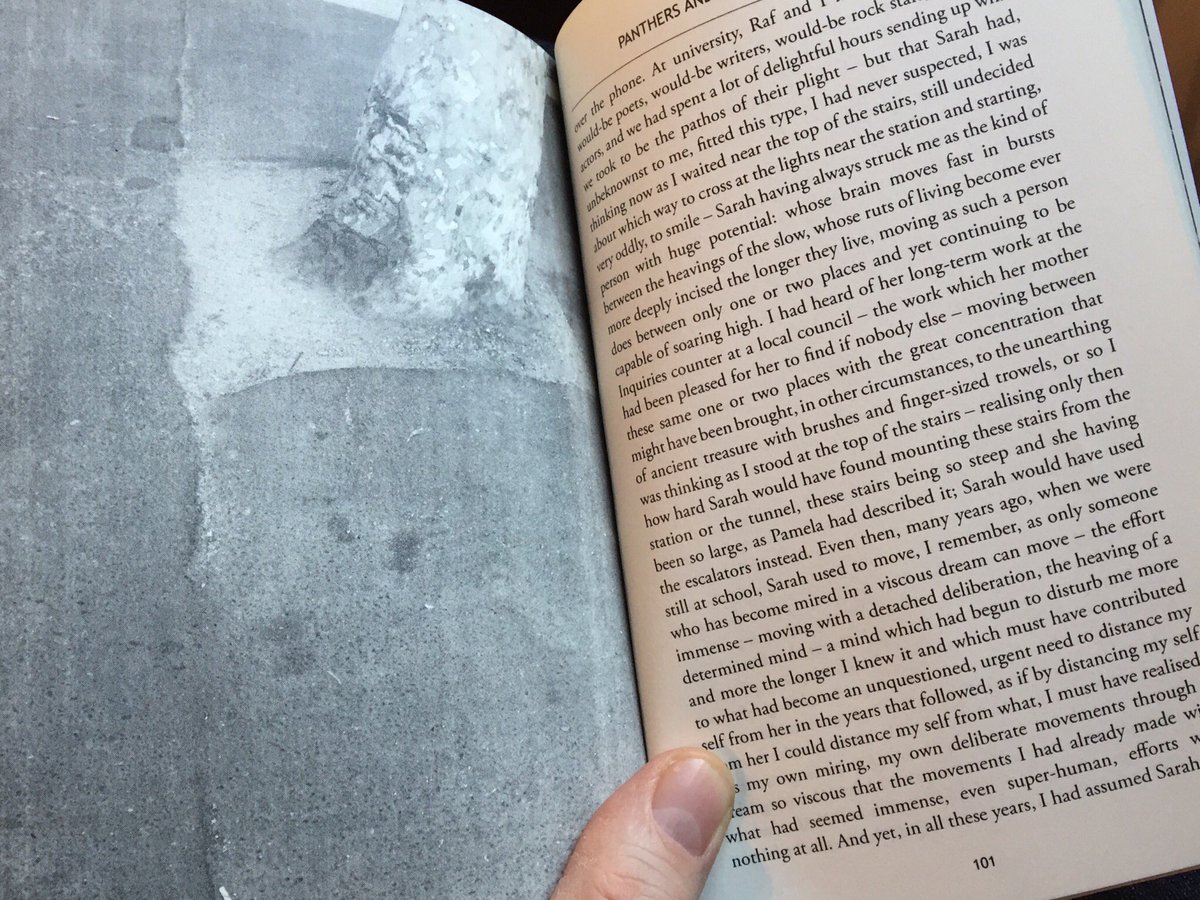

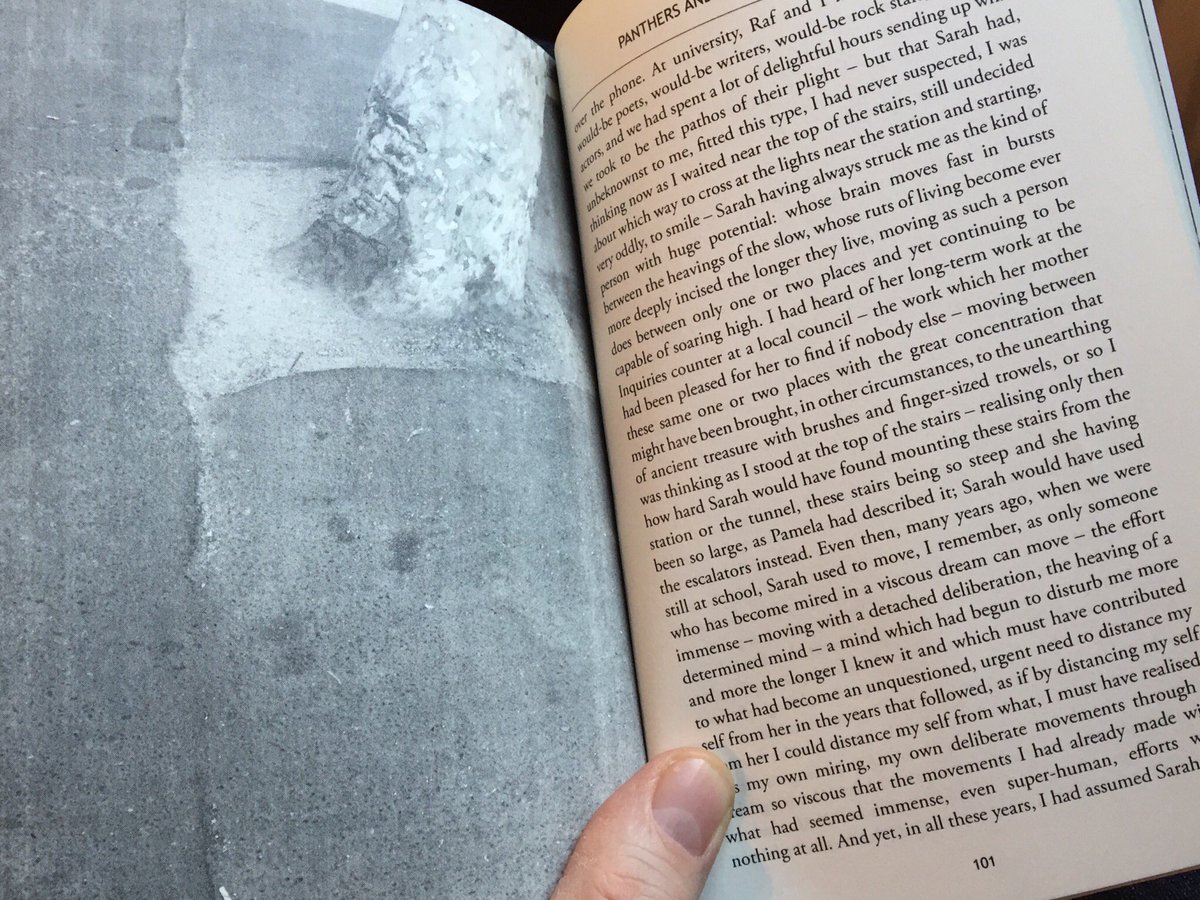

The use of photographs in the text (but - warning - not in the Kindle version) is immediately reminiscent of [a:W.G. Sebald|6580622|W.G. Sebald|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1465928875p2/6580622.jpg]. An example from Martin Shaw's Twitter feed (while I await my hardcopy):

but another influence (as on so many authors), one also highlighted by Shaw and acknowledged by the author, is my favourite writer of the 2nd half of the 20th Century, [a:Thomas Bernhard|7745|Thomas Bernhard|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1326833554p2/7745.jpg]. When asked about influences:

and later in the same interview she notes that her own breakthrough as a novelist came while reading Thomas Bernhard’s [b:Gargoyles|92571|Gargoyles|Thomas Bernhard|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1320473194s/92571.jpg|2529631]. And this concept of a breakthrough while reading a manuscript is key to the novella which opens:

For a long time I have dreamed of such a breakthrough, I thought as I set off from my flat in Glebe on that Monday morning – walking to a café in Crown Street for no other reason than to meet the sister, Pamela, so that I could give her back the manuscript Panthers and the Museum of Fire supposedly unread, as she had insisted on the phone only two days after she’d given it to me.

I have spent years and years of my life doing little more than work towards this very breakthrough. I have sacrificed love, holidays, sanity, my health, I told myself on my way up the street from the place where the building I lived in had mired itself in the roots of Moreton Bay figs and playground urine and the foetid remnants of plastic bags – doing nothing but work and work, or at least all the time just seeming to work and work, to get close to this breakthrough that might, indeed, have always escaped me because this is how I find it, and in spite of myself.

One notes immediately the (Bernhardian) thinking-while-walking, the indirect reported speech (here of her own thoughts) and the artistic obsessiveness. Although Craig doesn't produce a pale imitation of Bernhard, but very much creates her own personal work and style.

The concept of the novel is that the narrator, a radio-station worker and aspiring author called (like the actual author, although this is not auto-fiction) Jen Craig, recently attended the funeral of an old school friend, Sarah (her death possibly caused by obesity). At the wake afterwards, Sarah's sister, Pamela, practically foisted on her a completed by unpublished manuscript written by Sarah, asking for Jen's views, appealing to her literary flair, as she called it. Jen had had no intention of reading the manuscript but, when receiving a call from Pamela a few days later asking, without explanation, for her to return it unread, she decides to read it, and thereby obtains a decisive breakthrough in her own writing.

The novel itself has her recall her thoughts as she walks across Sydney - a walk described in precise detail - to meet Pamela, reflecting on the events of the funeral and subsequently as well as her acquaintance with Sarah. And much of this is told via a recollection, and indirect report, of a conversation between reading the manuscript and the walk which took place while preparing a dinner with her friend Raf - the various stages of the preparation also described in some detail. So one ends up with sentence structures such as:

Sarah has always been someone, I said to Raf that time, I was remembering now as I was walking towards Pamela in the café in Surry Hills.

As mentioned, the journey across Sydney is described in block-by-block detail and I suspect that this part may give even greater pleasure for those who know the streets in intimate detail. This promotional video for the book was certainly useful to give me an impression of some of the street scenes - https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Mb4OWAWEcGo - but I would agree with the author that my lack of knowledge of Sydney didn't over hinder my understanding:

The act of believing is a selfish one, I muttered, as I would like to have muttered to Sarah, no matter that it was far too late to talk to her. I wanted to be a writer and in order to do this I’d had to renounce everything else; I’d made a deal with God – a deal that I had worked so it was entirely beneficial to my interests; it was weighted towards me (I have to face this, I told myself – just keep remembering your self-justifications, and you might have a chance of facing this) – because I’d said to this God: I will believe in You so long as You make me a great, a famous writer, which surely only You have in Your power to confer.

or her (as the author's) unfortunate name - ironic given her anorexia - as after she was born it was adopted by a multinational dieting company (https://www.jennycraig.com/), something that particularly struck her when, a couple of years earlier, she had encountered the morbidly obese Sarah in the street, after having (somewhat deliberately) lost contact for many years:

Sarah had cut through to me with the kind of greeting that I hadn’t heard in years. Sarah called me Jenny, of course, which nobody but my parents call me these days – my parents preferring to ignore the fact that they had called their daughter after, though in advance of, a multinational dieting company, I had said to Raf who immediately laughed as I was hoping he would – and so Sarah called me Jenny and I had to stop walking and say hello.

and indeed a distinctively Bernhardian tribute to the pleasure of rants:

Pamela has always been an interferer, I had then gone on to say in definite tones, as a way of leading Raf towards another rant I wanted to make – another whose anticipation had already brought heat to my cheeks and the usual numbed, even trembling, incompetence to my lips and my words.

Thinking-while-walking (a la [a:Robert Walser|16073|Robert Walser|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1521957553p2/16073.jpg], Bernhard and Sebald) is key to the narrator's way of life (again an interesting link to reading-while-walking in Milkman):

all my life – or at least since the time that I was anorexic, when to walk was the ultimate pleasure, the only existence possible – I have attempted to understand my self by taking walks and I have always arrived somewhere with apparently more simply formulated thoughts and a sense that thinking is possible, and that I know what I’m doing or at least what I have been trying to do. I make connections as I walk, I was realising as I got closer and closer to the end of the tunnel, and I am always being buoyed by the unexpected, serendipitous connections between one train of thought and another, and yet the connections that I fashion in my brain through the repetitive, inevitable rhythm of my walking could well have no reality, no veracity, I was realising, or trying to realise, outside these peculiar ambulatory conditions of my mind

As for the unusual title of both this novel and the (fictional) manuscript - the explanation is rather prosaic. It is taken from a real-life (although no longer existant) road-sign in Western Sydney, en route to the Blue Mountains which read: Panthers and the Museum of Fire Use Route Number Fourteen, the Museum of Fire (https://www.museumoffire.net/) being aimed at aspiring junior firefighters, and the Panthers the name of the local rugby team in Penrith:

Although Sarah had called her manuscript Panthers and the Museum of Fire – or at least had written this title on the front of the manuscript, writing it in her handwriting, if in fact it was her handwriting and not someone else’s – it has been so long since I can recall ever seeing her handwriting – the manuscript seemed to have nothing to do with this title: all the suggestive allure that I might have expected from a title like that. I recognised the wording at once when Pamela gave me the manuscript at Sarah’s wake, passing it on to me despite my best attempts not to take it. Anyone would have recognised the wording, anyone who has ever driven along the east–west motorway of Sydney. It was the wording of a sign, of course. The title was a sign – an ordinary sign – a large white-on-brown sign that sits on the side of a road, of the sort that denotes trails or destinations of supposed tourist or heritage interest, in this case for the drivers of cars or trucks that might want to turn off the motorway to go to the rugby league club Panthers, named, as I’ve learned by Googling, not after the mysterious animal that is said to be wandering the Blue Mountains, confounding all attempts to capture it or even to prove it exists, but because a woman called Deidre won a competition to name the club in 1964: the name Panthers being only one of her many suggestions, her many animal-name suggestions.

Highly recommended: and if by a British author and publisher would have been a shoo-in for the Goldsmiths Prize.

Quoting the narrator quoting Virginia Woolf:

A manuscript about everything and also about nothing: a hold-all object, as Virginia Woolf says – a manuscript in which everything is possible, everything can be written.

This wonderful novella came to my attention via a tweet from Martin Shaw @booksdesk:

Word, what an outstanding novel this is (from 2015)! Makes me feel once more that Oz so badly needs a Goldsmiths-style prize to give bold fictions such as this some exposure (they turn up on the edges of existing prizes sometimes, but seldom seem to get s/listed or win)Panthers and the Museum of Fire was indeed longlisted but not shortlisted for the 2016 Stella Prize in Australia - the judges' report read:

Panthers and the Museum of Fire is about a woman returning a manuscript to the sister of its deceased writer. It is immersively written in a stream-of-consciousness style that takes the reader directly into her reflections on life, friendship and, importantly, her own writing.I would not agree with the 'stream-of-of-consciousness' description (one rather overused in a rather lazy fashion by reviewers - see also [b:Milkman|36047860|Milkman|Anna Burns|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1526985855s/36047860.jpg|57622946]), since the narrator's thoughts here are carefully reconstructed after the event, but the reference to European modernist techniques is apposite.

The unpretentious truths and agonies, soul-searching and tenuous self-regard of the artist’s life are brilliantly and immediately depicted, in writing that deploys European modernist literary techniques in an Australian setting. In Jen Craig’s novella, voice, character and vocation combine in a sophisticated and accessible narrative.

The use of photographs in the text (but - warning - not in the Kindle version) is immediately reminiscent of [a:W.G. Sebald|6580622|W.G. Sebald|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1465928875p2/6580622.jpg]. An example from Martin Shaw's Twitter feed (while I await my hardcopy):

but another influence (as on so many authors), one also highlighted by Shaw and acknowledged by the author, is my favourite writer of the 2nd half of the 20th Century, [a:Thomas Bernhard|7745|Thomas Bernhard|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1326833554p2/7745.jpg]. When asked about influences:

It is interesting that you can see something in this work that could be compared to Joyce’s Ulysses. If this is so, it is completely unconscious. Of course, there is the walking through a city – I can see that – and the way the main action or event in the book occurs in a single day – a single morning, even (and before work!). But apart from that: my piece is one, undivided work – a single throw, if you like, and is actually much closer to Proust, despite its brevity. But having said that, I can see that the simple fact that my narrator is a woman, and that she is also rather breathlessly pressed in her narration, could have something of Molly Bloom’s monologue about it – a kind of Molly Bloom taking over the male patterning of things but not one to play into the fantasies that they might have of her, nor even what women often have about themselves, as sexual beings, as women. I think Orhan Pamuk’s short novel, [b:The New Life|11694|The New Life|Orhan Pamuk|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1329921999s/11694.jpg|374005], was an important influence on this novella. Although I have read it twice, I haven’t read it for some years – and all that remains of it in my head, apart from some images of people hurrying along the streets carrying grey plastic bags, and the extraordinary glare and speed of night bus journeys, is something of its urgency and its focus – its sheer determination. Another important influence has been [a:Thomas Bernhard|7745|Thomas Bernhard|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1326833554p2/7745.jpg], who was the first to show me that so much didn’t need to be written at all, that you could cut to the quick – which for me, as for him, I think, are the driving nature of thoughts and the way they play out. I grew up in a household that was presided over by a very dramatic, hyperbolic and vividly expressive if usually contradictory monologist and it took me the work of Thomas Bernhard – first Christina Stead’s, but later Thomas Bernhard’s, to make me aware, very slowly, of what I could do with this dominating part of my experience in terms of form.from https://shortaustralianstories.com.au/q-a-with-jen-craig/

and later in the same interview she notes that her own breakthrough as a novelist came while reading Thomas Bernhard’s [b:Gargoyles|92571|Gargoyles|Thomas Bernhard|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1320473194s/92571.jpg|2529631]. And this concept of a breakthrough while reading a manuscript is key to the novella which opens:

For a long time I have dreamed of such a breakthrough, I thought as I set off from my flat in Glebe on that Monday morning – walking to a café in Crown Street for no other reason than to meet the sister, Pamela, so that I could give her back the manuscript Panthers and the Museum of Fire supposedly unread, as she had insisted on the phone only two days after she’d given it to me.

I have spent years and years of my life doing little more than work towards this very breakthrough. I have sacrificed love, holidays, sanity, my health, I told myself on my way up the street from the place where the building I lived in had mired itself in the roots of Moreton Bay figs and playground urine and the foetid remnants of plastic bags – doing nothing but work and work, or at least all the time just seeming to work and work, to get close to this breakthrough that might, indeed, have always escaped me because this is how I find it, and in spite of myself.

One notes immediately the (Bernhardian) thinking-while-walking, the indirect reported speech (here of her own thoughts) and the artistic obsessiveness. Although Craig doesn't produce a pale imitation of Bernhard, but very much creates her own personal work and style.

The concept of the novel is that the narrator, a radio-station worker and aspiring author called (like the actual author, although this is not auto-fiction) Jen Craig, recently attended the funeral of an old school friend, Sarah (her death possibly caused by obesity). At the wake afterwards, Sarah's sister, Pamela, practically foisted on her a completed by unpublished manuscript written by Sarah, asking for Jen's views, appealing to her literary flair, as she called it. Jen had had no intention of reading the manuscript but, when receiving a call from Pamela a few days later asking, without explanation, for her to return it unread, she decides to read it, and thereby obtains a decisive breakthrough in her own writing.

The novel itself has her recall her thoughts as she walks across Sydney - a walk described in precise detail - to meet Pamela, reflecting on the events of the funeral and subsequently as well as her acquaintance with Sarah. And much of this is told via a recollection, and indirect report, of a conversation between reading the manuscript and the walk which took place while preparing a dinner with her friend Raf - the various stages of the preparation also described in some detail. So one ends up with sentence structures such as:

Sarah has always been someone, I said to Raf that time, I was remembering now as I was walking towards Pamela in the café in Surry Hills.

As mentioned, the journey across Sydney is described in block-by-block detail and I suspect that this part may give even greater pleasure for those who know the streets in intimate detail. This promotional video for the book was certainly useful to give me an impression of some of the street scenes - https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Mb4OWAWEcGo - but I would agree with the author that my lack of knowledge of Sydney didn't over hinder my understanding:

I do think place is important. It always makes a huge difference where I am and where I walk, which is probably why I am such a creature of habit. Perhaps, too, that’s why I’ve been living in the same crumbling sandstock brick terrace for close on 23 years. Having said that, though, I don’t think it is necessary for the reader to know Sydney to understand what is going on in the book, because place, in this novella, is filtered, almost entirely, through the narrator’s head – it is the narrator’s version of Sydney, and many readers will probably disagree with her version. Many will not even recognise it.We also get diversions into the narrator's own personal history - her anorexia as well as her gain (at a religious camp with Sarah's believer family) and later loss of faith, from a form of Faustian pact but with God:

The act of believing is a selfish one, I muttered, as I would like to have muttered to Sarah, no matter that it was far too late to talk to her. I wanted to be a writer and in order to do this I’d had to renounce everything else; I’d made a deal with God – a deal that I had worked so it was entirely beneficial to my interests; it was weighted towards me (I have to face this, I told myself – just keep remembering your self-justifications, and you might have a chance of facing this) – because I’d said to this God: I will believe in You so long as You make me a great, a famous writer, which surely only You have in Your power to confer.

or her (as the author's) unfortunate name - ironic given her anorexia - as after she was born it was adopted by a multinational dieting company (https://www.jennycraig.com/), something that particularly struck her when, a couple of years earlier, she had encountered the morbidly obese Sarah in the street, after having (somewhat deliberately) lost contact for many years:

Sarah had cut through to me with the kind of greeting that I hadn’t heard in years. Sarah called me Jenny, of course, which nobody but my parents call me these days – my parents preferring to ignore the fact that they had called their daughter after, though in advance of, a multinational dieting company, I had said to Raf who immediately laughed as I was hoping he would – and so Sarah called me Jenny and I had to stop walking and say hello.

and indeed a distinctively Bernhardian tribute to the pleasure of rants:

Pamela has always been an interferer, I had then gone on to say in definite tones, as a way of leading Raf towards another rant I wanted to make – another whose anticipation had already brought heat to my cheeks and the usual numbed, even trembling, incompetence to my lips and my words.

Thinking-while-walking (a la [a:Robert Walser|16073|Robert Walser|https://images.gr-assets.com/authors/1521957553p2/16073.jpg], Bernhard and Sebald) is key to the narrator's way of life (again an interesting link to reading-while-walking in Milkman):

all my life – or at least since the time that I was anorexic, when to walk was the ultimate pleasure, the only existence possible – I have attempted to understand my self by taking walks and I have always arrived somewhere with apparently more simply formulated thoughts and a sense that thinking is possible, and that I know what I’m doing or at least what I have been trying to do. I make connections as I walk, I was realising as I got closer and closer to the end of the tunnel, and I am always being buoyed by the unexpected, serendipitous connections between one train of thought and another, and yet the connections that I fashion in my brain through the repetitive, inevitable rhythm of my walking could well have no reality, no veracity, I was realising, or trying to realise, outside these peculiar ambulatory conditions of my mind

As for the unusual title of both this novel and the (fictional) manuscript - the explanation is rather prosaic. It is taken from a real-life (although no longer existant) road-sign in Western Sydney, en route to the Blue Mountains which read: Panthers and the Museum of Fire Use Route Number Fourteen, the Museum of Fire (https://www.museumoffire.net/) being aimed at aspiring junior firefighters, and the Panthers the name of the local rugby team in Penrith:

Although Sarah had called her manuscript Panthers and the Museum of Fire – or at least had written this title on the front of the manuscript, writing it in her handwriting, if in fact it was her handwriting and not someone else’s – it has been so long since I can recall ever seeing her handwriting – the manuscript seemed to have nothing to do with this title: all the suggestive allure that I might have expected from a title like that. I recognised the wording at once when Pamela gave me the manuscript at Sarah’s wake, passing it on to me despite my best attempts not to take it. Anyone would have recognised the wording, anyone who has ever driven along the east–west motorway of Sydney. It was the wording of a sign, of course. The title was a sign – an ordinary sign – a large white-on-brown sign that sits on the side of a road, of the sort that denotes trails or destinations of supposed tourist or heritage interest, in this case for the drivers of cars or trucks that might want to turn off the motorway to go to the rugby league club Panthers, named, as I’ve learned by Googling, not after the mysterious animal that is said to be wandering the Blue Mountains, confounding all attempts to capture it or even to prove it exists, but because a woman called Deidre won a competition to name the club in 1964: the name Panthers being only one of her many suggestions, her many animal-name suggestions.

Highly recommended: and if by a British author and publisher would have been a shoo-in for the Goldsmiths Prize.

Quoting the narrator quoting Virginia Woolf:

A manuscript about everything and also about nothing: a hold-all object, as Virginia Woolf says – a manuscript in which everything is possible, everything can be written.

aquamarine's review

5.0

I ended up really enjoying this book. I do not agree with reviewers who label this book as stream-of-consciousness, using that term as if it meant pouring words artlessly onto the page which is not what Panthers does at all; rather I think the book performs stream-of-consciousness but reveals itself to be highly structured, spiralling through its themes and deepening them as it goes. I did struggle a bit with the first twenty pages; the seeming lack of structure made it hard for me to remember where I was and I often re-read passages. I like the long sentences; it was the long paragraphs that made it hard for me to grasp. This is not, however, a criticism, more just a recognition of the work I had to do to follow the book's method. Every novel teaches you how to read it, as James Wood says, and I think it's a shame some readers abandoned it at the moment the style would have taken hold, into what another reader described as a walking meditation, a thought I also had. We don't give novels very long these days to set out their wares, to teach us how to read them; instead we expect to come to them already knowing how to read them which will lead to the endless flow of formulaic work we are seeing on the market now. I don't think twenty pages is enough of a fair go.

Once things started falling into place I flowed through the book like the boat sailing over water that the author uses as a metaphor for writing at one point. Suddenly I was able to keep everything in my head and I fell into the rhythm of the prose. It was especially enjoyable for me as there was so much I could relate to, living the writerly life in the writerly place that the narrator yearns for - the Blue Mountains - and knowing every step the character takes in that part of the city and sharing so many of the experiences. How this novel would affect a reader who has not shared any of that experience I do not know but I don't see why it wouldn't work in some of the same way that Knausgaard does; after all I haven't shared any of the experiences of his narrator.

I loved the reflections on writing and also loved the reflections on books and reading, the peculiar despair of the book lover who can never read all the good books and is disappointed by so many books and oppressed by the enthusiasms and recommendations of others - this reminded me both of Orwell's thoughts on the pleasures of buying second-hand books and of course the wonderful passage near the beginning of Calvino's If on a Winter's Night a Traveller about the serried ranks of books lying in wait for us in every place and around every corner.

Thank you, Jen Craig. I found this book inspiring to the writer in me, just as your narrator found the eponymous manuscript inspiring to her self as a writer.

Once things started falling into place I flowed through the book like the boat sailing over water that the author uses as a metaphor for writing at one point. Suddenly I was able to keep everything in my head and I fell into the rhythm of the prose. It was especially enjoyable for me as there was so much I could relate to, living the writerly life in the writerly place that the narrator yearns for - the Blue Mountains - and knowing every step the character takes in that part of the city and sharing so many of the experiences. How this novel would affect a reader who has not shared any of that experience I do not know but I don't see why it wouldn't work in some of the same way that Knausgaard does; after all I haven't shared any of the experiences of his narrator.

I loved the reflections on writing and also loved the reflections on books and reading, the peculiar despair of the book lover who can never read all the good books and is disappointed by so many books and oppressed by the enthusiasms and recommendations of others - this reminded me both of Orwell's thoughts on the pleasures of buying second-hand books and of course the wonderful passage near the beginning of Calvino's If on a Winter's Night a Traveller about the serried ranks of books lying in wait for us in every place and around every corner.

Thank you, Jen Craig. I found this book inspiring to the writer in me, just as your narrator found the eponymous manuscript inspiring to her self as a writer.

More...