You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

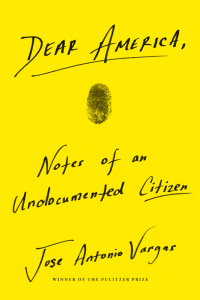

A compelling and human story. It opened my eyes further to the complexities of immigration and to the inhumanity of a system that labels any human "illegal."

A must read. A very insightful and enlightening story about the immigration process and misconceptions held by many.

Whew. A short but powerful read. Vargas is an undocumented American, a well-known and respected journalist and accidental activist. He was sent to the States as a young boy from the Philippines, his mother having paid a 'coyote' to accompany him to California, where he would live with his (naturalized) immigrant grandparents, who had moved over a decade prior. For many reasons out of his control, Vargas' grandparents never took him through the process of 'becoming legal', and he found out at the age of 16, when trying to get his drivers license, that his green card was fake.

"They conspired to send me to America to give me a better life without realizing they had created a nightmare scenario for me. And I was scared."

What follows is an examination of the challenges facing undocumented immigrants, the impossible hurdles blocking their path to citizenship -- ranging from finances, language barriers and an outdated and complicated system, to fear of deportation and misunderstanding of policies. One of the most intimidating roadblocks is the ten-year ban on re-entering the country that faces anyone who's lived here illegally for more than a certain period of time (I can't remember the specifics). One thing I did not realize prior was that after entering the country without documentation, there's no practical way to get on a path to legal residency and citizenship. So for many who are brought here as children, what are they to do??? It's a conundrum that our system cant solve in its current form.

"I wanted to keep repeating: there is no line. I wanted to scream over and over again: THERE IS NO LINE! THERE IS NO LINE! THERE IS NO LINE!"

Vargas is one of the lucky ones though, sitting in a place of privilege amongst undocumented immigrants, thanks to the neighborhood his grandparents lived in and the upper class high school he got to attend, where he met and befriended many adults who assisted him on his journey, through graduating, applying for college, getting a drivers license, paying his taxes, and finding paying work. He was fortunate enough to have dozens of *white* people on his side, helping him along the way.

"I don’t know why they did what they did. But I know for sure that all these Americans—all these strangers, all across the country—have allowed people like me to pass. If just five people—a friend, a co-worker, a classmate, a neighbor, a faith leader—helped one of the estimated 11 million undocumented people in our country, then illegal immigration as we know it would touch at least 66 million people."

"I told him that even though I know that they’re all white—physically, that is—I didn’t think of them as white people when I was growing up. I associated white people with people who make you feel inferior, people who condescend to you, people who question why you are the way you are without acknowledging that you, too, are a human being with the same needs and wants."

The chapters exploring how he got into journalism, and the guilt and shame he felt when having to lie on the initial job applications, were really eye opening for me, raising a lot of issues I hadn't thought about before. How would I have handled any of his situations? I tried to imagine finding out as a 16 year old, concerned with boys and driving and college plans, that I was not legally supposed to be here.... what would I have done? Would I have "turned myself in" or done what he did, and confided in people who could help me continue living in the place that I called home? What about once I made it to college, graduated, and had to find work? Surviving on underpaid under-the-table jobs wouldn't be realistic or feasible in order to get the work experience needed for a career (regardless of where I lived). So faking my way into work, paying my taxes, being as responsible a resident as possible, seems like the most logical choice.

"What would you have done? Work under the table? Stay under the radar? Not work at all? Which box would you check? What have you done to earn your box? Besides being born at a certain place in a certain time, did you have to do anything? Anything at all? If you wanted to have a career, if you wanted to have a life, if you wanted to exist as a human being, what would you have done?"

"There are many things this “illegal” cannot do. I cannot vote. Which ID will I use to vote? My American Express card? Though I’ve lived in this country for twenty-five years, though I pay all kinds of taxes, which I am happy and willing to pay, since I am a product of public schools and public libraries, I have no voice in the democratic process. Think of it as taxation without legalization. I cannot travel outside the United States. If I leave, there’s no guarantee that I’d be allowed back. I don’t have access to Obamacare or any government-funded health program. In fact, even though I started and oversee a nonprofit organization that provides benefits and health insurance to seventeen full-time staffers, I have to buy my own private health insurance."

As a memoir, this one is solid in terms of writing and structure, but not necessarily emotionally deep and not one of my favorites. I'd recommend it more as educational material than entertaining autobiography. Still, due to the subject matter, it was a page-turner, for me. I appreciated his approach to the subject (himself, immigration); as a journalist, Vargas always searches for the truth and aims for total transparency (hence his decision to 'come out' as undocumented nearly a decade ago). He definitely doesn't hold back in revealing his own flaws, mistakes, poor and/or questionable decisions, and in criticizing his own family for what they did to him (putting him in this scenario). But he also raises a lot of questions - of himself, of his family, of our nightmare immigration system and the way our country treats outsiders, and of what the future will hold.

However, despite his relentless pursuit of truth, it felt a bit emotionally distant... and perhaps that's a result of decades of putting up emotional walls between himself and his family, and any potential friends -- why get emotionally invested if you're constantly at risk of being forced to leave? Even so, you expect a memoir to be a bit more emotionally resonating. Also I felt like it ended a bit abruptly and had to go a'googling to find out 'what happened' so to speak (he's still living here and has not been deported, fyi). But overall, I would recommend this fast read to almost anyone living in America today as a starting point for civil discourse on a complicated issue.

"Citizenship is showing up. Citizenship is using your voice while making sure you hear other people around you. Citizenship is how you live your life. Citizenship is resilience."

Some other quotes that stood out to me:

"How do undocumented workers who have no legal papers pay income taxes? The government has no problem taking our money; it just won’t recognize that we have the right to earn it."

"Regardless of immigration status, all wage earners are required to pay federal taxes. Nationwide, the amount of taxes that the Internal Revenue Service collects from undocumented workers ranges from almost $2.2 million in Montana, which has an estimated undocumented population of four thousand, to more than $3.1 billion in California, which is home to more than three million undocumented immigrants. According to the nonpartisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, undocumented immigrants nationwide pay an estimated 8 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes on average. To put that in perspective, the top 1 percent of taxpayers pay an average nationwide effective tax rate of just 5.4 percent."

"Immigrants are seen as mere labor, our physical bodies judged by perceptions of what we contribute, or what we take. Our existence is as broadly criminalized as it is commodified. I don’t how many times I’ve explained to a fellow journalist that even though it is an illegal act to enter the country without documents, it is not illegal for a person to be in the country without documents. That is a clear and crucial distinction. I am not a criminal. This is not a crime."

"For the most part, why are white people called “expats” while people of color are called “immigrants”? Why are some people called “expats” while others are called “immigrants”? What’s the difference between a “settler” and a “refugee”? Language itself is a barrier to information, a fortress against understanding the inalienable instinct of human beings to move."

"Migration is the most natural thing people do, the root of how civilizations, nation-states, and countries were established. The difference, however, is that when white people move, then and now, it’s seen as courageous and necessary, celebrated in history books. Yet when people of color move, legally or illegally, the migration itself is subjected to question of legality."

"They conspired to send me to America to give me a better life without realizing they had created a nightmare scenario for me. And I was scared."

What follows is an examination of the challenges facing undocumented immigrants, the impossible hurdles blocking their path to citizenship -- ranging from finances, language barriers and an outdated and complicated system, to fear of deportation and misunderstanding of policies. One of the most intimidating roadblocks is the ten-year ban on re-entering the country that faces anyone who's lived here illegally for more than a certain period of time (I can't remember the specifics). One thing I did not realize prior was that after entering the country without documentation, there's no practical way to get on a path to legal residency and citizenship. So for many who are brought here as children, what are they to do??? It's a conundrum that our system cant solve in its current form.

"I wanted to keep repeating: there is no line. I wanted to scream over and over again: THERE IS NO LINE! THERE IS NO LINE! THERE IS NO LINE!"

Vargas is one of the lucky ones though, sitting in a place of privilege amongst undocumented immigrants, thanks to the neighborhood his grandparents lived in and the upper class high school he got to attend, where he met and befriended many adults who assisted him on his journey, through graduating, applying for college, getting a drivers license, paying his taxes, and finding paying work. He was fortunate enough to have dozens of *white* people on his side, helping him along the way.

"I don’t know why they did what they did. But I know for sure that all these Americans—all these strangers, all across the country—have allowed people like me to pass. If just five people—a friend, a co-worker, a classmate, a neighbor, a faith leader—helped one of the estimated 11 million undocumented people in our country, then illegal immigration as we know it would touch at least 66 million people."

"I told him that even though I know that they’re all white—physically, that is—I didn’t think of them as white people when I was growing up. I associated white people with people who make you feel inferior, people who condescend to you, people who question why you are the way you are without acknowledging that you, too, are a human being with the same needs and wants."

The chapters exploring how he got into journalism, and the guilt and shame he felt when having to lie on the initial job applications, were really eye opening for me, raising a lot of issues I hadn't thought about before. How would I have handled any of his situations? I tried to imagine finding out as a 16 year old, concerned with boys and driving and college plans, that I was not legally supposed to be here.... what would I have done? Would I have "turned myself in" or done what he did, and confided in people who could help me continue living in the place that I called home? What about once I made it to college, graduated, and had to find work? Surviving on underpaid under-the-table jobs wouldn't be realistic or feasible in order to get the work experience needed for a career (regardless of where I lived). So faking my way into work, paying my taxes, being as responsible a resident as possible, seems like the most logical choice.

"What would you have done? Work under the table? Stay under the radar? Not work at all? Which box would you check? What have you done to earn your box? Besides being born at a certain place in a certain time, did you have to do anything? Anything at all? If you wanted to have a career, if you wanted to have a life, if you wanted to exist as a human being, what would you have done?"

"There are many things this “illegal” cannot do. I cannot vote. Which ID will I use to vote? My American Express card? Though I’ve lived in this country for twenty-five years, though I pay all kinds of taxes, which I am happy and willing to pay, since I am a product of public schools and public libraries, I have no voice in the democratic process. Think of it as taxation without legalization. I cannot travel outside the United States. If I leave, there’s no guarantee that I’d be allowed back. I don’t have access to Obamacare or any government-funded health program. In fact, even though I started and oversee a nonprofit organization that provides benefits and health insurance to seventeen full-time staffers, I have to buy my own private health insurance."

As a memoir, this one is solid in terms of writing and structure, but not necessarily emotionally deep and not one of my favorites. I'd recommend it more as educational material than entertaining autobiography. Still, due to the subject matter, it was a page-turner, for me. I appreciated his approach to the subject (himself, immigration); as a journalist, Vargas always searches for the truth and aims for total transparency (hence his decision to 'come out' as undocumented nearly a decade ago). He definitely doesn't hold back in revealing his own flaws, mistakes, poor and/or questionable decisions, and in criticizing his own family for what they did to him (putting him in this scenario). But he also raises a lot of questions - of himself, of his family, of our nightmare immigration system and the way our country treats outsiders, and of what the future will hold.

However, despite his relentless pursuit of truth, it felt a bit emotionally distant... and perhaps that's a result of decades of putting up emotional walls between himself and his family, and any potential friends -- why get emotionally invested if you're constantly at risk of being forced to leave? Even so, you expect a memoir to be a bit more emotionally resonating. Also I felt like it ended a bit abruptly and had to go a'googling to find out 'what happened' so to speak (he's still living here and has not been deported, fyi). But overall, I would recommend this fast read to almost anyone living in America today as a starting point for civil discourse on a complicated issue.

"Citizenship is showing up. Citizenship is using your voice while making sure you hear other people around you. Citizenship is how you live your life. Citizenship is resilience."

Some other quotes that stood out to me:

"How do undocumented workers who have no legal papers pay income taxes? The government has no problem taking our money; it just won’t recognize that we have the right to earn it."

"Regardless of immigration status, all wage earners are required to pay federal taxes. Nationwide, the amount of taxes that the Internal Revenue Service collects from undocumented workers ranges from almost $2.2 million in Montana, which has an estimated undocumented population of four thousand, to more than $3.1 billion in California, which is home to more than three million undocumented immigrants. According to the nonpartisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, undocumented immigrants nationwide pay an estimated 8 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes on average. To put that in perspective, the top 1 percent of taxpayers pay an average nationwide effective tax rate of just 5.4 percent."

"Immigrants are seen as mere labor, our physical bodies judged by perceptions of what we contribute, or what we take. Our existence is as broadly criminalized as it is commodified. I don’t how many times I’ve explained to a fellow journalist that even though it is an illegal act to enter the country without documents, it is not illegal for a person to be in the country without documents. That is a clear and crucial distinction. I am not a criminal. This is not a crime."

"For the most part, why are white people called “expats” while people of color are called “immigrants”? Why are some people called “expats” while others are called “immigrants”? What’s the difference between a “settler” and a “refugee”? Language itself is a barrier to information, a fortress against understanding the inalienable instinct of human beings to move."

"Migration is the most natural thing people do, the root of how civilizations, nation-states, and countries were established. The difference, however, is that when white people move, then and now, it’s seen as courageous and necessary, celebrated in history books. Yet when people of color move, legally or illegally, the migration itself is subjected to question of legality."

emotional

informative

inspiring

sad

medium-paced

Every American, documented or otherwise, should read this book. While Vargas’ story is unique, he offers a personable, emotional account of someone who wishes to be here legally, but the system won’t allow it. Profoundly tragic and somehow hopeful.

This book is a great look into the reasons why some immigrants simply cannot "do it the right way". Being married to a foreigner myself I know that the path to citizenship is not easy and for some is not an option. Great read.

Eyeopening perspective as the author writes a memoir and love letter to America.

One of my favorite autobiographies. Jose Antonio Vargas describes the troubles he faced being brought to the United States from the Philippines as a child without his mother. He discusses common misconceptions about the path to citizenship (which for many is nonexistent) and the struggles he faced growing up gay with pressure from his family to marry a woman to get citizenship. This is such an important perspective especially in today’s times.

Very interesting book. Legal documentation in this country is ridiculously misunderstood and "coming the legal way" is so much easier said than done.