Take a photo of a barcode or cover

dark

funny

informative

medium-paced

informative

reflective

slow-paced

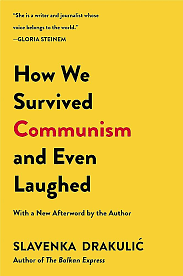

I don't really recall how this book made its way into my collection. Though given the topic, I suspect my sister, Jessa, may have been involved. This book is a collection of essays about what life was like for women in Eastern Europe under Communist regimes. These stories are mostly about deprivation: sharing small apartments with multiple families, the changing availability of toilet paper, repairing nylons over and over and over again, hoarding food, supplies, even plastic bags, because you never know when they will disappear from the stores. A Western reporter visits, and notes in her article as a sign of their deprivation that women still wash their clothing in tubs of boiling water here, and Drakulić is annoyed, devoting an entire essay to laundry.

There is some devoted to the consequences of communism that are already familiar to us -- the censors, the party line, the extensive wire-tapping, the government-controlled media. But precisely because these are the known stories, Drakulić brings them all back to how they affect women. It takes a while to sink in that no matter how many Cold Ware movies we've seen, no matter how many fat Russian novels we've read, these stories are new. Even now, ten years after it was written, this book is still a revelation.

Spoiler: There's not really a whole lot of laughter.

There is some devoted to the consequences of communism that are already familiar to us -- the censors, the party line, the extensive wire-tapping, the government-controlled media. But precisely because these are the known stories, Drakulić brings them all back to how they affect women. It takes a while to sink in that no matter how many Cold Ware movies we've seen, no matter how many fat Russian novels we've read, these stories are new. Even now, ten years after it was written, this book is still a revelation.

Spoiler: There's not really a whole lot of laughter.

emotional

informative

reflective

fast-paced

— Тебе це, мабуть, здивує, люба, але знаєш, люди мусять жити й виживати і під час воєн. Як би ми інакше пережили комунізм?

Читаючи цю книжку я ніби дивилася на жінок у своїй сім'ї. Мені пощастило народитися вже в незалежній Україні, проте дуже багато описаних епізодів траплялися і в моєму житті. Зрозуміла природу деяких речей і ще більше зненавиділа совок.

Хороша література, буду тепер всім товкти її прочитати))

This is an excellent book that I'd never heard of -- the author is Croatian and a little older than me and writes powerfully about the lived experience of women in Eastern European countries under Communism. It is very sobering to read about how dreadful and bleak life is under that regime.

Highly recommended to everyone these days given Russia's ascendancy and so many misled people thinking that authoritarian governments somehow serve anyone besides the ruling class.

Highly recommended to everyone these days given Russia's ascendancy and so many misled people thinking that authoritarian governments somehow serve anyone besides the ruling class.

This is an interesting, engaging, and insightful look into life under communist regimes across Eastern Europe, with an emphasis on women's lives. I learned a lot and enjoyed reading.

کمونیسم همزمان که رختشو از یه کشوری میبنده، جلوپلاسشو یه جای دیگه پهن میکنه. تنها زمینه ای که کمونیسم توش موفق شد همه گیر کردن فقر بود، البته نه همه...

In 1994, at the age of 21, I spent a summer living with a family in Eastern Europe. It was my first opportunity to see first hand the difficulties families, and especially women, faced in their everyday lives.

I spent the summer exploring a country where the people I met were friendly and unfailingly generous.

While my other American friends and I sometimes laughed to ourselves about the things we found strange in the culture - the out of date clothes, the overwhelming smell of body odor on the public transit, the drunkenness, and the strong smell of urine in the stairways and elevators of our buildings - we also romanticized a lot. People were resourceful. There was no almost no urban sprawl. Public transit was available and wonderfully easy to use.

I have a particularly cringe-worthy memory of telling my host mother that life in her country was so much less stressful and laid back than life in my own country. This after she'd woken up before dawn to get her son off to school, made breakfast for the whole family, caught the subway to work, worked the whole day at a job she didn't like because her husband was an invalid and an alcoholic and she was the sole provider for the family, stopped at the market on the way home, and finished off her day by cooking us all dinner and washing the dishes. My excuse for such an idiotic comment is that I was young, selfish, and reveling in the free time which came with being unemployed for the first time since I'd turned 16.

It wasn't Drakulic's book that made me first realize how wrong I'd been, but I did spend quite a few chapters of it wishing I could go back to 1994 for a re-do. I'd have tried to understand what my host mother was going through. I'd have cooked dinner for a change. And, yes, I'd give her my leftover stash of tampons and sanitary napkins before I left.

As a Western liberal, I also squirmed uncomfortably as I read Drakulic describe her own ill-ease discussing communism with my ilk. Yes, I had to admit, I've probably been guilty of defending things about communism, a system I've never had to live under myself, that weren't defensible. To be fair, though, we Western liberals of a certain generation were raised to believe communism was evil and everything about it was bad. We were raised on propaganda. How shocked we were to find that, like any system, communism had some positives. People looked out for each other more than they did where I came from. There weren't homeless people on the street begging. In fact the hotel I stayed in during a 1990 visit housed people and families who in my own country would have been left to sleep under bridges or on park benches. There was very little waste. People repaired and used what they had. Public transportation was available and for the most part reliable. The countryside was beautiful and accessible, because people lived in dense cities and the countryside was reserved for dachas which could be reached by train.

Is that too apologetic for an oppressive system? Maybe. But as an outsider who has lived with not just the positives but also the negatives of a capitalist society for her whole life, I don't think it is a bad thing to admit that there were some things the communists got right and wonder if we couldn't do a little bit better ourselves by copying those things (and leaving the things they didn't to so well behind, of course).

I spent the summer exploring a country where the people I met were friendly and unfailingly generous.

While my other American friends and I sometimes laughed to ourselves about the things we found strange in the culture - the out of date clothes, the overwhelming smell of body odor on the public transit, the drunkenness, and the strong smell of urine in the stairways and elevators of our buildings - we also romanticized a lot. People were resourceful. There was no almost no urban sprawl. Public transit was available and wonderfully easy to use.

I have a particularly cringe-worthy memory of telling my host mother that life in her country was so much less stressful and laid back than life in my own country. This after she'd woken up before dawn to get her son off to school, made breakfast for the whole family, caught the subway to work, worked the whole day at a job she didn't like because her husband was an invalid and an alcoholic and she was the sole provider for the family, stopped at the market on the way home, and finished off her day by cooking us all dinner and washing the dishes. My excuse for such an idiotic comment is that I was young, selfish, and reveling in the free time which came with being unemployed for the first time since I'd turned 16.

It wasn't Drakulic's book that made me first realize how wrong I'd been, but I did spend quite a few chapters of it wishing I could go back to 1994 for a re-do. I'd have tried to understand what my host mother was going through. I'd have cooked dinner for a change. And, yes, I'd give her my leftover stash of tampons and sanitary napkins before I left.

As a Western liberal, I also squirmed uncomfortably as I read Drakulic describe her own ill-ease discussing communism with my ilk. Yes, I had to admit, I've probably been guilty of defending things about communism, a system I've never had to live under myself, that weren't defensible. To be fair, though, we Western liberals of a certain generation were raised to believe communism was evil and everything about it was bad. We were raised on propaganda. How shocked we were to find that, like any system, communism had some positives. People looked out for each other more than they did where I came from. There weren't homeless people on the street begging. In fact the hotel I stayed in during a 1990 visit housed people and families who in my own country would have been left to sleep under bridges or on park benches. There was very little waste. People repaired and used what they had. Public transportation was available and for the most part reliable. The countryside was beautiful and accessible, because people lived in dense cities and the countryside was reserved for dachas which could be reached by train.

Is that too apologetic for an oppressive system? Maybe. But as an outsider who has lived with not just the positives but also the negatives of a capitalist society for her whole life, I don't think it is a bad thing to admit that there were some things the communists got right and wonder if we couldn't do a little bit better ourselves by copying those things (and leaving the things they didn't to so well behind, of course).

dark

emotional

sad

slow-paced