You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

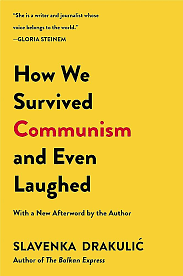

I really wanted to like this book more than I did. There's a lot of good information about the lives of average people living in Eastern Europe under the iron curtain and I feel like I understand the daily struggles people faced a little better now. But given that...it should have been more compelling than it was. There are definitely a couple of essays in the book that are worth reading, but this is a book to borrow rather than a book to buy.

Dark, funny, and beautiful, this series of essays gets into the details of living under communism, a level we don't hear about enough in the 'West'. Powerful prose and a must read for anyone who loves personal essays that dig into deeper insights.

This was DNF for me. I'm not sure what I expected it from it, but I thought it would make me think and maybe reveal a fresh perspective that I hadn't considered on an interesting topic area. It did not.

I made it just under halfway through, and found it both incredibly depressing and more like the author was trying to be poignant and failing. One of the first few short stories literally ends with "After all, beauty is in the eye of the beholder" as though that's some pithy new phrase to make you think.

Also, this very much felt like someone trying to shove 'communism bad, capitalism good' down my throat the entire time (which I don't precisely disagree with or anything but it is SO heavy-handed), and I feel like the author in many ways wrote about the people in these former communist areas in a way similar to early twentieth century authors discussing people in cultures not their own. Not quite outright exoticizing them, but something similar in shape.

I really wanted to like this book and I just didn't.

I made it just under halfway through, and found it both incredibly depressing and more like the author was trying to be poignant and failing. One of the first few short stories literally ends with "After all, beauty is in the eye of the beholder" as though that's some pithy new phrase to make you think.

Also, this very much felt like someone trying to shove 'communism bad, capitalism good' down my throat the entire time (which I don't precisely disagree with or anything but it is SO heavy-handed), and I feel like the author in many ways wrote about the people in these former communist areas in a way similar to early twentieth century authors discussing people in cultures not their own. Not quite outright exoticizing them, but something similar in shape.

I really wanted to like this book and I just didn't.

Дуже кінематографічна книга, багато образів та історій, вартих візуалізації

challenging

emotional

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

tense

medium-paced

This is one of my favorite books. Draculic speaks to me on a personal level - a must-read for any historian or feminist.

adventurous

challenging

dark

emotional

informative

reflective

fast-paced

The book is great, and it really makes you think. It outlines the heritage of communism that lives on to this day in ex-communist countries. The epilogue is one of those “big bad Serbs” stories, but since it was written in 1993 I can understand how it would’ve been hard to be objective and not give a one sided story.

کتاب بیش از حدی که مستحقش بوده امتیاز دریافت کرده. برام عجیبه چطور حرفای یه مقالهنویس جهاندیده میتونه مثل غرغرای رانندهتاکسیای خطای شلوغ تهران باشه. اون نگاه "این شهرستانیا که کونشون رو با سنگ میشورن اومدن شهر ما رو شلوغ و خراب کردن" هم توی اون مقالهی دربارهی کاغذ توالت آشکار بود. شاید به خاطر شباهتهای فرهنگی زندگی دهه 60 ما با زندگی اونا بود. قدرت گرفتن طبقهی پاییندست بر تهرانیهای بااصالتی که از کوروش خرید میکردند".

خلاصه که هیچ دوستش نداشتم.

خلاصه که هیچ دوستش نداشتم.

وقتی بیشتر مردم با شنیدن واژه "جنگ" به یاد سربازای اسلحه بهدست و خسته از دویدن ها و سر دزدیدن های پیوسته میوفتن، اسلاونکا دراکولیچ مارو به پشت زمین های خاکی، به عمق زندگی زنان و مردمان مسنی میبره که خوردن یک لیوان شیر، براشون آرزو شده.

کمتر نویسندگانی مثل خانم دراکولیچ هستن که حاضر میشن ماه ها رو در کنار شخصیت های کتاب هاشون بنشینن، به حرف ها و داستان هاشون گوش بدن و بعد به گوش ما مردم اینجایی برسونن. این کتاب نگاه شمارو به باب های جدیدی از اثرات جنگ، نیازهای مردم و احساساتشون جلب میکنه که لایق خواندن و اندیشه هستن. ترجمه روان و ملموسی داشت؛ خوندنش رو پیشنهاد میکنم.

کمتر نویسندگانی مثل خانم دراکولیچ هستن که حاضر میشن ماه ها رو در کنار شخصیت های کتاب هاشون بنشینن، به حرف ها و داستان هاشون گوش بدن و بعد به گوش ما مردم اینجایی برسونن. این کتاب نگاه شمارو به باب های جدیدی از اثرات جنگ، نیازهای مردم و احساساتشون جلب میکنه که لایق خواندن و اندیشه هستن. ترجمه روان و ملموسی داشت؛ خوندنش رو پیشنهاد میکنم.