Take a photo of a barcode or cover

So long. So heavy.

Nonfiction November.

I'm glad it's done.

Nonfiction November.

I'm glad it's done.

I don't agree with everything the author said or did in this book but I was moved by his compassion and empathy toward a population of people who desperately need it. I was particularly struck by the accuracy of the chapter on politics. Many of the stories and facts in this book rang true for me on a personal level.

I got into the middle of chapter two and found myself not in the right mental state to finish the book. I would pick up this book again, when it's a better time for me.

Such an in-depth and carefully detailed book. An atlas, yes. The black cloud and all its meteorology. So complete that it is very very very difficult to finish each section without coming up for air by skipping ahead.

Really helped me understand depression. The symptoms are different from what I expected. I thought being depressed had something to do with sadness. It's more like being unable to function.

So I didn't ACTUALLY finish reading this, because I got what I needed out of it within he first one hundred or so pages, and had no ambition to finish the other three to four hundred. I definitely recommend the first few chapters, especially if you or a loved one is struggling with severe depression. It definitely accurately depicts what it feels like to be depressed. I believe Solomon says something like, "depression is not sadness... It is the opposite of vitality." Nothing else much comes close to describing depression for me.

My favorite book on depression. Brilliant. I could not have read it while deeply depressed, but I read it the year after and it was so affirming.

The Noonday Demon review: depression embraced, calmed and then studied…

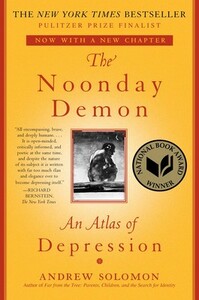

THE NOONDAY DEMON

By “Andrew Solomon”

The noonday demon digs deep into the personal history of Solomon as he narrates, brilliantly and terrifyingly, his own agonizing experience of depression. He also portrays the pain of others, in different cultures and societies whose lives have been altered by depression and uncovers the historical, social, biological chemical, and medical implications of this crippling disease.

I would start this review as Solomon started this book, with my own, mild yet appalling, encounter with depression: I had fought it before as well the year before. It may have lasted for a couple of months, but then it went away. I got used to the life away from my family and friends and my hometown, studying in a university with people I never knew until this point in my life. I believed that just the way it came, it has lifted and I am over with it. To name it depression at that time was absurd; maybe it was just homesickness at worst, I thought.

Then the next year, I left home again for the university after spending the 3-month summer vacation at home. And just like last year, it started to feel gloomy again. The matters were even worse this time around because a few friends that I had made last year and shared my hostel room with, had left. I was alone again, just like the first time I came here. And soon enough, things started to get ugly bad. Though I was deeply sad and felt empty inside, like the life had been sucked out of me, I now started to have moments where I would get afraid of no reason at all. I would start shaking and I was worried to the most extreme of levels for no reason that I could think of. They were ‘panic attacks’ and ‘anxiety’, I later came to know, but at that time, I knew no medical terms regarding the mental diseases. Like most other people, mental disease, I thought, were the ones that make you crazy; or that depression was a disease too luxurious to have for a boy from a middle-class family like me.

Sure enough, I thought it would pass off like the previous time, and everyone I talked to about this, told me the same thing, which made me believe it even more. But it was also taken so lightly by everyone that after sometime, it started to irritate me; I felt like I was being taken lightly that whatever I said seemed to not bother others. And finally it got the worst, I couldn’t bear it any longer. I, then, against my extreme frugality, which is a symptom of my depression, went to seek a psychiatrist and paid a hefty 3,000PKRs, which as I had feared, worsened my state even more. My mind played this trick on me that no medicine would cure me now because it has gotten so worse, and since antidepressants take time to function, I got played into that trick. Funny though, I asked my friend to come with me to the doctor’s appointment, and when he saw me, he laughed and shrugged that I didn’t look sick at all and that I was ‘completely fine’.

And that’s one of the threatening sides of depression: others can’t see it or believe it, and even you yourself don’t believe it at times as well. But as you go through it while neglecting it, and shrugging it off as something too insignificant to shatter someone as strong as you, you get shattered even worse. It is dark in depths of it and it completely covers you; and through it or rather with it, you see that defeating realities of life in general, but with more harshness and urgency: you will die, there is a lot of suffering, none of it matters, you are pathetic, why is that bagger still alive, why do people laugh, why people can’t see that they are alone, why people are blind to the indifference of everyone. Depression not only banishes you of the worldly joys, but makes you rather devilishly wise to see that everyone are faking theirs as well. “It is not that you are lonely,” writes Solomon, “but that everyone else is too.”

Of course I understood none of these while I was suffering for the 5 months with this disabling disease, because that’s what it did to me: it disabled me. But once I came out of it, slowly, and thank God and me and all those who helped me come out of it, I began to thirst to solve this enigma of depression. I first heard Solomon during the early stages of my depression. I discovered this book and even read some of it, I listened to his talks about depression, but quite frankly, none of it worked for me at that time, just like nothing else at all worked me for. There also remained this lingering fear that this noonday demon would come again, because as the name suggests, it attacks you in the brightness of the day, it does not fear. This worked as a motivator for me to start reading this book, and later I even purchased the paperback copy of it for 1,700PKRs, and I wasn’t bothered at all – where once I measured the route to my university from my hostel to see which is the nearest, even if by a minute or two, so that I could save some 10PKRs on petrol.

In this book, Solomon doesn’t only talk about depression, he lives with it and lives with all kinds of depression as well. He has written about depression in almost all ways you can even imagine writing about it. He hasn’t only used his own misery with depression as a way to reach to the core of depression, but rather as a motivator to go out and reach people who have suffered from it in almost all walks of life and in almost all other ways, mildly or worse.

As you flip one page after another, you get sucked into this book by the insights it offers through the stories it has to tell. You read Dickenson’s darkly insightful poems about her struggles with depression many years in the past, and also about many characters that are suffering from it now. And slowly your burdens, by the shared knowledge about this disease, seems less awful in comparison; you begin to feel sympathy rather than rage.

Solomon has done a great deal of research and reached out to many people for writing this book in this fulfilling way; and I don’t know this because I read an article about it, or that it is written on the cover on this book, but by reading it. Solomon’s story, after you finish reading, is but only one of the many stories that you read this book. Only such selflessness can bring about a book this healing in nature to a disease otherwise too hard to bear.

In the early four chapters of this book (depression, breakdowns, treatments & alternatives) Solomon quickly attends to the matter at hand: depression. And tries to give the patient, or reader, a sense that he hasn’t actually gone mad and that his suffering is shared by many across the world. And these four chapters are so philosophically insightful and written by Solomon with such kindness that the readers feel understood and therefore loved – here’s the calmness that they sought amidst the chaos that they had been going through.

Solomon was also very much aware that pain or suffering is very subjective; and therefore it is super hard to even come close to the realization that what the other person is going through. But the stories you read in this book horrifies you and brings you to tears at more than one point. While he has done justice to the stories of others by sharing it in such intimate ways with the readers, on the other hand, he has also offered many types of solution to depression and thus, given hope to many that you can come out of it, or at least suffer in a more manageable way until you do.

The following chapters, then, start to expand the topic so much so that the patient’s own misery seems almost bearable. And not only that, these chapters get the readers fascinated as they come to know so much about their disease where until now no one even believed it even existed. You explore about its history, addictions along with depression, about the link between poverty and depression, about suicide and the haunting stories around it, and about the politics regarding depression and politics around its treatment. This extensive knowledge works not as a medicine but a therapy in session.

All of these chapters are thorough and complete in way that you never actually thought about. The way Solomon has approached each chapters and explored its almost every angle is really something you awe at. In the chapter, Suicide, he has been very open and true at the same time, to the story of his own mother’s death, because of cancer, and in some ways, rather her suicide. While at first such suicide, which I won’t spoil, might seem unthinkable even, but as Solomon researches about this utmost saddening act of taking one’s life, and in turn, gives his own explanations about it, it then doesn’t seem so excruciating. You than begin to understand the suicidal people more in depth, and sometimes, even understand their actions.

But through all these chapters, you never for once, feel disengaged or put off in any sense. Although you are learning things that may not be directly related to you, all of it is however related to the disease that you are suffering from. And knowing about all of it doesn’t overwhelm you as you might expect, but rather gives you a more complete and thorough sketch about your suffering and the illness you are suffering from.

These different perspectives and stories about depression is in itself a healing process to the unheard and misunderstood patients of depression. While it may not tell you the secret about how not to get depressed as most of the people and videos on the internet tell you to, but it teaches you, through including you into the circle of these sufferers, a rather important and vital skill: how to suffer in depression or even better how to learn from it.

While you first hate it: the depression, the lifelessness, the lack of energy and interest, your poor diet, the guilt, the weakness, the cries, the loneliness, the hopelessness, the suicidal thoughts, or the life itself with all its grandness, this book first and foremost soothes you, and then teaches you about what is happening to you. And by the end, even invites you to love your depression and learn from the dark wisdoms of it. This book is an education on its own.

But to be able to do this, you need to walk a fine line between sounding wise or sounding a madman, and Solomon does that perfectly. He never tries to side himself against or with depression; against the unbearable and insufferable pains of it or with the insightful and uncommon wisdoms of it. He walks that fine line for the 576 page. And when he does, at the end of the book, declare that he loves his depression, you clearly see what he means – I am grateful for it too now.

The amount of research and effort put into this book is more than worthy of appreciation or awards. As you have suffered from depression, and while you are suffering from it, to write the accounts of you painful experiences and to have the courage to listen to the even more horrifying stories of others take some courage that not everyone possesses. Or to go through the burdensome work of extensive research about this topic while being crippled by depression is profoundly incredible.

But I will say this, that in doing so, Solomon felt joy and found purpose, not only to understand his own misery but to help others understand theirs. This is a service both to oneself and also a rare one to those who can’t help themselves. It was a service to me!

An Excerpt:

“Seek out the memories depression takes away and project them into the future. Be brave; be strong; take your pills.”

“To regret my depression would be to regret the most fundamental part of myself.”

This is such a complete, groundbreaking, preaching, and vital book for all those who suffer from depression, which is most of us today. Solomon has put years of his life into writing this book and it serves us in the best way possible. Such books are rare; rare because only few are successful at dissolving the reader into its pages and put them back out after they have finished reading, as a more aware person about the thesis that they started reading this book for; it consoles you wholly. Thank you, Solomon – thank you for understanding me and in turn making me capable of understanding myself. Your book is fully and well received.

My praise for the novel:

Consoling, complete, and powerful; I am specifically better because of this book.

A rare masterpiece!

Rating: 5/5 *****

A review by: Ejaz Hussain

August 29, 2019

THE NOONDAY DEMON

By “Andrew Solomon”

The noonday demon digs deep into the personal history of Solomon as he narrates, brilliantly and terrifyingly, his own agonizing experience of depression. He also portrays the pain of others, in different cultures and societies whose lives have been altered by depression and uncovers the historical, social, biological chemical, and medical implications of this crippling disease.

I would start this review as Solomon started this book, with my own, mild yet appalling, encounter with depression: I had fought it before as well the year before. It may have lasted for a couple of months, but then it went away. I got used to the life away from my family and friends and my hometown, studying in a university with people I never knew until this point in my life. I believed that just the way it came, it has lifted and I am over with it. To name it depression at that time was absurd; maybe it was just homesickness at worst, I thought.

Then the next year, I left home again for the university after spending the 3-month summer vacation at home. And just like last year, it started to feel gloomy again. The matters were even worse this time around because a few friends that I had made last year and shared my hostel room with, had left. I was alone again, just like the first time I came here. And soon enough, things started to get ugly bad. Though I was deeply sad and felt empty inside, like the life had been sucked out of me, I now started to have moments where I would get afraid of no reason at all. I would start shaking and I was worried to the most extreme of levels for no reason that I could think of. They were ‘panic attacks’ and ‘anxiety’, I later came to know, but at that time, I knew no medical terms regarding the mental diseases. Like most other people, mental disease, I thought, were the ones that make you crazy; or that depression was a disease too luxurious to have for a boy from a middle-class family like me.

Sure enough, I thought it would pass off like the previous time, and everyone I talked to about this, told me the same thing, which made me believe it even more. But it was also taken so lightly by everyone that after sometime, it started to irritate me; I felt like I was being taken lightly that whatever I said seemed to not bother others. And finally it got the worst, I couldn’t bear it any longer. I, then, against my extreme frugality, which is a symptom of my depression, went to seek a psychiatrist and paid a hefty 3,000PKRs, which as I had feared, worsened my state even more. My mind played this trick on me that no medicine would cure me now because it has gotten so worse, and since antidepressants take time to function, I got played into that trick. Funny though, I asked my friend to come with me to the doctor’s appointment, and when he saw me, he laughed and shrugged that I didn’t look sick at all and that I was ‘completely fine’.

And that’s one of the threatening sides of depression: others can’t see it or believe it, and even you yourself don’t believe it at times as well. But as you go through it while neglecting it, and shrugging it off as something too insignificant to shatter someone as strong as you, you get shattered even worse. It is dark in depths of it and it completely covers you; and through it or rather with it, you see that defeating realities of life in general, but with more harshness and urgency: you will die, there is a lot of suffering, none of it matters, you are pathetic, why is that bagger still alive, why do people laugh, why people can’t see that they are alone, why people are blind to the indifference of everyone. Depression not only banishes you of the worldly joys, but makes you rather devilishly wise to see that everyone are faking theirs as well. “It is not that you are lonely,” writes Solomon, “but that everyone else is too.”

Of course I understood none of these while I was suffering for the 5 months with this disabling disease, because that’s what it did to me: it disabled me. But once I came out of it, slowly, and thank God and me and all those who helped me come out of it, I began to thirst to solve this enigma of depression. I first heard Solomon during the early stages of my depression. I discovered this book and even read some of it, I listened to his talks about depression, but quite frankly, none of it worked for me at that time, just like nothing else at all worked me for. There also remained this lingering fear that this noonday demon would come again, because as the name suggests, it attacks you in the brightness of the day, it does not fear. This worked as a motivator for me to start reading this book, and later I even purchased the paperback copy of it for 1,700PKRs, and I wasn’t bothered at all – where once I measured the route to my university from my hostel to see which is the nearest, even if by a minute or two, so that I could save some 10PKRs on petrol.

In this book, Solomon doesn’t only talk about depression, he lives with it and lives with all kinds of depression as well. He has written about depression in almost all ways you can even imagine writing about it. He hasn’t only used his own misery with depression as a way to reach to the core of depression, but rather as a motivator to go out and reach people who have suffered from it in almost all walks of life and in almost all other ways, mildly or worse.

As you flip one page after another, you get sucked into this book by the insights it offers through the stories it has to tell. You read Dickenson’s darkly insightful poems about her struggles with depression many years in the past, and also about many characters that are suffering from it now. And slowly your burdens, by the shared knowledge about this disease, seems less awful in comparison; you begin to feel sympathy rather than rage.

Solomon has done a great deal of research and reached out to many people for writing this book in this fulfilling way; and I don’t know this because I read an article about it, or that it is written on the cover on this book, but by reading it. Solomon’s story, after you finish reading, is but only one of the many stories that you read this book. Only such selflessness can bring about a book this healing in nature to a disease otherwise too hard to bear.

In the early four chapters of this book (depression, breakdowns, treatments & alternatives) Solomon quickly attends to the matter at hand: depression. And tries to give the patient, or reader, a sense that he hasn’t actually gone mad and that his suffering is shared by many across the world. And these four chapters are so philosophically insightful and written by Solomon with such kindness that the readers feel understood and therefore loved – here’s the calmness that they sought amidst the chaos that they had been going through.

Solomon was also very much aware that pain or suffering is very subjective; and therefore it is super hard to even come close to the realization that what the other person is going through. But the stories you read in this book horrifies you and brings you to tears at more than one point. While he has done justice to the stories of others by sharing it in such intimate ways with the readers, on the other hand, he has also offered many types of solution to depression and thus, given hope to many that you can come out of it, or at least suffer in a more manageable way until you do.

The following chapters, then, start to expand the topic so much so that the patient’s own misery seems almost bearable. And not only that, these chapters get the readers fascinated as they come to know so much about their disease where until now no one even believed it even existed. You explore about its history, addictions along with depression, about the link between poverty and depression, about suicide and the haunting stories around it, and about the politics regarding depression and politics around its treatment. This extensive knowledge works not as a medicine but a therapy in session.

All of these chapters are thorough and complete in way that you never actually thought about. The way Solomon has approached each chapters and explored its almost every angle is really something you awe at. In the chapter, Suicide, he has been very open and true at the same time, to the story of his own mother’s death, because of cancer, and in some ways, rather her suicide. While at first such suicide, which I won’t spoil, might seem unthinkable even, but as Solomon researches about this utmost saddening act of taking one’s life, and in turn, gives his own explanations about it, it then doesn’t seem so excruciating. You than begin to understand the suicidal people more in depth, and sometimes, even understand their actions.

But through all these chapters, you never for once, feel disengaged or put off in any sense. Although you are learning things that may not be directly related to you, all of it is however related to the disease that you are suffering from. And knowing about all of it doesn’t overwhelm you as you might expect, but rather gives you a more complete and thorough sketch about your suffering and the illness you are suffering from.

These different perspectives and stories about depression is in itself a healing process to the unheard and misunderstood patients of depression. While it may not tell you the secret about how not to get depressed as most of the people and videos on the internet tell you to, but it teaches you, through including you into the circle of these sufferers, a rather important and vital skill: how to suffer in depression or even better how to learn from it.

While you first hate it: the depression, the lifelessness, the lack of energy and interest, your poor diet, the guilt, the weakness, the cries, the loneliness, the hopelessness, the suicidal thoughts, or the life itself with all its grandness, this book first and foremost soothes you, and then teaches you about what is happening to you. And by the end, even invites you to love your depression and learn from the dark wisdoms of it. This book is an education on its own.

But to be able to do this, you need to walk a fine line between sounding wise or sounding a madman, and Solomon does that perfectly. He never tries to side himself against or with depression; against the unbearable and insufferable pains of it or with the insightful and uncommon wisdoms of it. He walks that fine line for the 576 page. And when he does, at the end of the book, declare that he loves his depression, you clearly see what he means – I am grateful for it too now.

The amount of research and effort put into this book is more than worthy of appreciation or awards. As you have suffered from depression, and while you are suffering from it, to write the accounts of you painful experiences and to have the courage to listen to the even more horrifying stories of others take some courage that not everyone possesses. Or to go through the burdensome work of extensive research about this topic while being crippled by depression is profoundly incredible.

But I will say this, that in doing so, Solomon felt joy and found purpose, not only to understand his own misery but to help others understand theirs. This is a service both to oneself and also a rare one to those who can’t help themselves. It was a service to me!

An Excerpt:

“Seek out the memories depression takes away and project them into the future. Be brave; be strong; take your pills.”

“To regret my depression would be to regret the most fundamental part of myself.”

This is such a complete, groundbreaking, preaching, and vital book for all those who suffer from depression, which is most of us today. Solomon has put years of his life into writing this book and it serves us in the best way possible. Such books are rare; rare because only few are successful at dissolving the reader into its pages and put them back out after they have finished reading, as a more aware person about the thesis that they started reading this book for; it consoles you wholly. Thank you, Solomon – thank you for understanding me and in turn making me capable of understanding myself. Your book is fully and well received.

My praise for the novel:

Consoling, complete, and powerful; I am specifically better because of this book.

A rare masterpiece!

Rating: 5/5 *****

A review by: Ejaz Hussain

August 29, 2019

Abbreviation of everything below: I recommend reading the first two chapters and skimming the rest.

“I know nothing," the painter Gerhard Richter once wrote. "I can do nothing. I understand nothing. I know nothing. Nothing. And all this misery does not even make me particularly unhappy.” (45)

Solomon, in the middle of his own depression, went through a monumental effort to write this book. And my whine of it is that maybe he aimed a bit too monumental.

Solomon began the book strong, but a few hundred pages in the writing becomes a little mind-numbing. Long paragraphs where every sentence is eleven words long. He begins writing things like “the chances of eliminating depression through genetic manipulation any time soon are, I believe, thinner than thin ice” (172). First-chapter Solomon would never have allowed “thinner than thin ice.”

This could also be the fault of content. Solomon can really shine when he’s engaged in a lyrical explanation of how it feels to have depression, the subject of the first two chapters and also a bit of the very end. But his ambition to write an ATLAS of depression draws him out of his sphere of competence.

He's not a great science writer. He's focused on anecdotes and doesn't compellingly or clearly address the disagreements in the scholarly literature -- and while his own experience doesn’t go out of date 13 years on, that’s not the case with the neuroscience he's writing about. But this isn’t as bad as his attempt to write about the politics of mental health. He starts off by discounting Foucault with a facile misreading (Michel says hospitalizing the mentally diseased is just a way to stop the revolution, man! But he's wrong, because the depressed are bad revolutionaries!). This is particularly unfortunate because Foucault could have provided some tools for thinking through the quandaries that Solomon inevitably butts up against: should people have “the right to be depressed”? Won’t they thank us afterwards if we forcefully institutionalize them and fix ‘em up? Well, but also, admits Solomon, those hospitals are the most dreadful place imaginable and he would never want to be trapped in one. And wait -- who's going to make this decision? (And maybe “the right to be depressed” actually means the right to not be forcefully medicated, electroshocked, and locked up -- when you put it that way it doesn’t sound so crazy).

Through all of this, Solomon is spot-on in rejecting anyone who romanticizes depression. But I still feel uncomfortable with the ease with which he pushes psychopharmacological treatment. He mentions a recommendation in the New England Journal of Medicine that depressive symptoms lasting more than two months after the death of a loved one should be given antidepressant therapy, and I can’t help but think of Hamlet: “O heavens! Die two months ago and not forgotten yet? Then there’s hope a great man’s memory may outlive his life half a year.”

Oh and then -- then he has to go into the “evolution” section. Bring on the evo-psy. First we must understand the human animal as a rigidly hierarchical species. “Someone is always top dog; a society without a leader is chaotic and soon dissolves” (404). When you fight to improve your rank order and lose, it’s adaptive for you to be depressed so you don’t keep fighting and cause stress in the group. Sure, you could just as easily say humans are built for egalitarianism (and show instead that most societies reliant on rigid leaders are non-adaptive and, in the long run, dissolve), and perhaps the artificial introduction of extensive rank-order (following the invention of agriculture) builds depression into the system. Which is maybe why, after all, depression isn’t a disease of ambitious young men, but mostly of women and the elderly and the poor. But for some reason, it's not proper evo-psy if it's not weighted toward an apology for the worst characteristics of modern society.

To back a gee-whiz-we're-advanced hypothesis, Solomon argues that depression results from having so many choices in modern society: “In 1957, an average American supermarket had sixty-five items in the produce section: shoppers knew what all the fruits and vegetables were and had had each of them before. In 1997, an average American supermarket had over three hundred items in the produce section, with many markets pushing a thousand. You are in the realm of uncertainty even when you select your own dinner. This kind of escalation of choices is not convenient; it is dizzying” (409). He's probably right that there's something mentally unsettling in having to choose a job and religion and country to live in. But the produce-aisle argument was too much for me: we're expected to ignore the fact that for most of human existence we have been surrounded by explosive biodiversity. Next to a hunter-gatherer diet, the supermarket is a space of radical homogeneity. Our brains can handle 300 types of plants -- there’s something else that happens in the supermarket to depress you.

Solomon concludes with a tiresome “well anyway what’s natural?” argument, and a grasping attempt to say there’s a soul and there’s free will no matter what happens to the chemicals in our brain. It feels like he thinks he's a coach of a team of depressives and has to give us a slow-clap-worthy battle-speech before we go out on the field and fight our own brains. This is at odds with the better argument he makes, which is that depression can teach us to be more understanding and forgiving of others, because we can’t ever know what’s happening in the emotional life of another person, and how much ‘force of character’ -- whatever that means -- is required to keep a person kind and patient.

And then in addition to all this there's:

The Privilege Squirms:

Solomon seems to have been born into the owning class, which is also the home base of a lot of his buddies. To his credit, he works hard to dispel the myth that depression is a disease of the privileged. You still may find yourself squirming when you read about his friend finding relief from depression in childhood by having her parents buy her a pony.

Early on in the book, Solomon talks with a Cambodian refugee who works to treat depression in other refugee women. I thought this was a pretty good example of how to incorporate depression-diversity. A bad example would be when Solomon, using his generous book advance for ‘research,’ goes to Darkest Africa to undergo a traditional healing ceremony. Medical ethnotourism in search of a picturesque shaman. You’ll get the willies every time he says something like “Africa is a continent of incongruities” (168). Or says the African women “danced hysterically” (oh no, black ladies with wandering wombs!). Or after all the ram's blood and fire concludes “we came home with the buoyant feeling of having done something festive.”

Solomon brings up the idea that different races and ethnicities experience depression differently. Since depression is very much shaped by one’s culture, this is probably true. However, Solomon only supplies anecdotes -- ‘my friend, who’s Dominican, was like this’ -- which means he never moves out of the space of easy racial stereotypes. My guess is this does more harm than good.

Kudos to the man for having an entire chapter on poverty, how it encourages depression and how it complicates treatment. And yet I squirmed through the whole thing. One reason is because it’s always Othering to The Poors. The second is that within a limited, reformist politics Solomon has no choice but to be incoherent about solutions. Because he can’t say “Oh, end poverty, mental health shouldn’t be a commodity,” he has to instead find little pockets of ways governments could maybe give a little more funding here and there for an outreach program or two.

When he’s writing about women’s depression (the majority of all depression), he begins with a good and respectful explanation of the daily repressions and microaggressions women face in their daily lives, and how that can contribute to mental disease. He then, unfortunately, has to show he aint no looney feminist but rather a reasoned moderate, so he tries to reductio-ad-absurdum the writing of one feminist, and concludes another feminist’s quote with “and on and on and on” (177). Way to critique feminists by essentially putting fingers in his ears and saying “blah blah blah I can’t hear you.”

The main point being proffered by these wacko feminists (and by the existentialists, who receive much the same treatment from Solomon -- a very American rejection of the lot as just too dour to take seriously) is that there’s something non-pathological about being depressed when existence is the way that it is. Solomon later shows the research that depressives have a more accurate perception of themselves and of the world, and “mental health” is bought only at the price of embracing some illusions. The thinkers that Solomon rejects as too extreme -- like Camus -- actually work through this reality, while Solomon can only wobble back and forth between accepting the value of our depressiveness and embracing nevertheless some illusory Hope.

p.s. one more vote downwards for referring to a woman as “obscenely fat” (389). Her body isn’t an obscenity, bro.

“I know nothing," the painter Gerhard Richter once wrote. "I can do nothing. I understand nothing. I know nothing. Nothing. And all this misery does not even make me particularly unhappy.” (45)

Solomon, in the middle of his own depression, went through a monumental effort to write this book. And my whine of it is that maybe he aimed a bit too monumental.

Solomon began the book strong, but a few hundred pages in the writing becomes a little mind-numbing. Long paragraphs where every sentence is eleven words long. He begins writing things like “the chances of eliminating depression through genetic manipulation any time soon are, I believe, thinner than thin ice” (172). First-chapter Solomon would never have allowed “thinner than thin ice.”

This could also be the fault of content. Solomon can really shine when he’s engaged in a lyrical explanation of how it feels to have depression, the subject of the first two chapters and also a bit of the very end. But his ambition to write an ATLAS of depression draws him out of his sphere of competence.

He's not a great science writer. He's focused on anecdotes and doesn't compellingly or clearly address the disagreements in the scholarly literature -- and while his own experience doesn’t go out of date 13 years on, that’s not the case with the neuroscience he's writing about. But this isn’t as bad as his attempt to write about the politics of mental health. He starts off by discounting Foucault with a facile misreading (Michel says hospitalizing the mentally diseased is just a way to stop the revolution, man! But he's wrong, because the depressed are bad revolutionaries!). This is particularly unfortunate because Foucault could have provided some tools for thinking through the quandaries that Solomon inevitably butts up against: should people have “the right to be depressed”? Won’t they thank us afterwards if we forcefully institutionalize them and fix ‘em up? Well, but also, admits Solomon, those hospitals are the most dreadful place imaginable and he would never want to be trapped in one. And wait -- who's going to make this decision? (And maybe “the right to be depressed” actually means the right to not be forcefully medicated, electroshocked, and locked up -- when you put it that way it doesn’t sound so crazy).

Through all of this, Solomon is spot-on in rejecting anyone who romanticizes depression. But I still feel uncomfortable with the ease with which he pushes psychopharmacological treatment. He mentions a recommendation in the New England Journal of Medicine that depressive symptoms lasting more than two months after the death of a loved one should be given antidepressant therapy, and I can’t help but think of Hamlet: “O heavens! Die two months ago and not forgotten yet? Then there’s hope a great man’s memory may outlive his life half a year.”

Oh and then -- then he has to go into the “evolution” section. Bring on the evo-psy. First we must understand the human animal as a rigidly hierarchical species. “Someone is always top dog; a society without a leader is chaotic and soon dissolves” (404). When you fight to improve your rank order and lose, it’s adaptive for you to be depressed so you don’t keep fighting and cause stress in the group. Sure, you could just as easily say humans are built for egalitarianism (and show instead that most societies reliant on rigid leaders are non-adaptive and, in the long run, dissolve), and perhaps the artificial introduction of extensive rank-order (following the invention of agriculture) builds depression into the system. Which is maybe why, after all, depression isn’t a disease of ambitious young men, but mostly of women and the elderly and the poor. But for some reason, it's not proper evo-psy if it's not weighted toward an apology for the worst characteristics of modern society.

To back a gee-whiz-we're-advanced hypothesis, Solomon argues that depression results from having so many choices in modern society: “In 1957, an average American supermarket had sixty-five items in the produce section: shoppers knew what all the fruits and vegetables were and had had each of them before. In 1997, an average American supermarket had over three hundred items in the produce section, with many markets pushing a thousand. You are in the realm of uncertainty even when you select your own dinner. This kind of escalation of choices is not convenient; it is dizzying” (409). He's probably right that there's something mentally unsettling in having to choose a job and religion and country to live in. But the produce-aisle argument was too much for me: we're expected to ignore the fact that for most of human existence we have been surrounded by explosive biodiversity. Next to a hunter-gatherer diet, the supermarket is a space of radical homogeneity. Our brains can handle 300 types of plants -- there’s something else that happens in the supermarket to depress you.

Solomon concludes with a tiresome “well anyway what’s natural?” argument, and a grasping attempt to say there’s a soul and there’s free will no matter what happens to the chemicals in our brain. It feels like he thinks he's a coach of a team of depressives and has to give us a slow-clap-worthy battle-speech before we go out on the field and fight our own brains. This is at odds with the better argument he makes, which is that depression can teach us to be more understanding and forgiving of others, because we can’t ever know what’s happening in the emotional life of another person, and how much ‘force of character’ -- whatever that means -- is required to keep a person kind and patient.

And then in addition to all this there's:

The Privilege Squirms:

Solomon seems to have been born into the owning class, which is also the home base of a lot of his buddies. To his credit, he works hard to dispel the myth that depression is a disease of the privileged. You still may find yourself squirming when you read about his friend finding relief from depression in childhood by having her parents buy her a pony.

Early on in the book, Solomon talks with a Cambodian refugee who works to treat depression in other refugee women. I thought this was a pretty good example of how to incorporate depression-diversity. A bad example would be when Solomon, using his generous book advance for ‘research,’ goes to Darkest Africa to undergo a traditional healing ceremony. Medical ethnotourism in search of a picturesque shaman. You’ll get the willies every time he says something like “Africa is a continent of incongruities” (168). Or says the African women “danced hysterically” (oh no, black ladies with wandering wombs!). Or after all the ram's blood and fire concludes “we came home with the buoyant feeling of having done something festive.”

Solomon brings up the idea that different races and ethnicities experience depression differently. Since depression is very much shaped by one’s culture, this is probably true. However, Solomon only supplies anecdotes -- ‘my friend, who’s Dominican, was like this’ -- which means he never moves out of the space of easy racial stereotypes. My guess is this does more harm than good.

Kudos to the man for having an entire chapter on poverty, how it encourages depression and how it complicates treatment. And yet I squirmed through the whole thing. One reason is because it’s always Othering to The Poors. The second is that within a limited, reformist politics Solomon has no choice but to be incoherent about solutions. Because he can’t say “Oh, end poverty, mental health shouldn’t be a commodity,” he has to instead find little pockets of ways governments could maybe give a little more funding here and there for an outreach program or two.

When he’s writing about women’s depression (the majority of all depression), he begins with a good and respectful explanation of the daily repressions and microaggressions women face in their daily lives, and how that can contribute to mental disease. He then, unfortunately, has to show he aint no looney feminist but rather a reasoned moderate, so he tries to reductio-ad-absurdum the writing of one feminist, and concludes another feminist’s quote with “and on and on and on” (177). Way to critique feminists by essentially putting fingers in his ears and saying “blah blah blah I can’t hear you.”

The main point being proffered by these wacko feminists (and by the existentialists, who receive much the same treatment from Solomon -- a very American rejection of the lot as just too dour to take seriously) is that there’s something non-pathological about being depressed when existence is the way that it is. Solomon later shows the research that depressives have a more accurate perception of themselves and of the world, and “mental health” is bought only at the price of embracing some illusions. The thinkers that Solomon rejects as too extreme -- like Camus -- actually work through this reality, while Solomon can only wobble back and forth between accepting the value of our depressiveness and embracing nevertheless some illusory Hope.

p.s. one more vote downwards for referring to a woman as “obscenely fat” (389). Her body isn’t an obscenity, bro.

An interesting mix of research and memoir. It includes descriptions of the author's own experience of depression, and those of many people he interviewed in the course of writing the book. He also provides much background, including the history of how depression has been understood and treated going back to early Greece. Another chapter focuses on poverty, describing the occurrence and treatment (or lack of it) of the disease in that community. It's a big book and I did a fair amount of skimming, but learned a lot.