Take a photo of a barcode or cover

I’m really torn about my thoughts on this one; I wanted to love it but it just wasn’t my fav. The author has such a beautiful way with words, but I feel like this was something I’d read in high school and then have to be quizzed on all the symbolism within.

challenging

dark

sad

adventurous

challenging

dark

emotional

inspiring

mysterious

reflective

sad

challenging

dark

inspiring

reflective

sad

tense

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

emotional

hopeful

reflective

sad

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

Beautifully written. I found this story to be emotional, reflective, and just overall incredibly beautiful. While sad and challenging to read in many ways, these stories need told and need read.

emotional

inspiring

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

challenging

dark

emotional

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

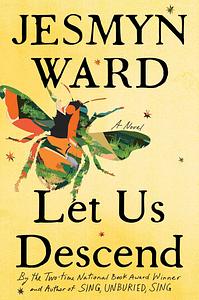

From the title, this novel excited me because I love an Inferno-inspired retelling. As the novel quickly points out, Let Us Descend is taken from a line of the Inferno and follows Annis (or sometimes Arese), a young slave who can trace her ancestry to a coterie of African warriors. After being sold off and separated from her Mother and close lover by the hands of her biological father--her "sire"--Annis seeks freedom, autonomy, and a return to the love and grace that slavery seeks to rob every living being of.

I have read a number of slave narratives over the years, and an Inferno-framing—a descent into hell, guided by the spirits of the past, only to come out the other side changed—seemed ripe for both metaphoric and structural picking. This is where Let Us Descend succeeds in many ways, with the obvious and necessary difference being that Dante left hell relatively unscathed, where Annis’ journey through Georgia and Louisiana is anything but: spirits guide her, characters weave in and out of Annis’ narrative like stitchwork, and no shortage of horrors arise from the humid alleys of New Orleans and sugarcane fields that chained so many thousands of slaves. Ward even takes her prose, already elevated, and dials it up to 11 in a clear nod to both the mythopoetic circumstances of Annis’ journey and the literal poetic text that the novel takes inspiration from.

I have read a number of slave narratives over the years, and an Inferno-framing—a descent into hell, guided by the spirits of the past, only to come out the other side changed—seemed ripe for both metaphoric and structural picking. This is where Let Us Descend succeeds in many ways, with the obvious and necessary difference being that Dante left hell relatively unscathed, where Annis’ journey through Georgia and Louisiana is anything but: spirits guide her, characters weave in and out of Annis’ narrative like stitchwork, and no shortage of horrors arise from the humid alleys of New Orleans and sugarcane fields that chained so many thousands of slaves. Ward even takes her prose, already elevated, and dials it up to 11 in a clear nod to both the mythopoetic circumstances of Annis’ journey and the literal poetic text that the novel takes inspiration from.

Oddly, it is this more than anything that kept me at arm’s length from the novel’s rich telling. Characters feel incidental, a mixture of too-obvious and too-sidelined to feel like meaningful components on Annis’ journey; the spirit world proves either far too chatty without substance or far too deus ex machina in when it decides to assist Annis (which, to the novel's credit, is a major point of contention; the main spirit, a storm-and-wrath woman named Aza, has a breakneck hot-and-cold relationship with Annis, which points towards the novel's general themes of freedom and autonomy); the pacing odd, at times riotous and at others stubborn. Yet it is the telling that dampens all of these elements, the brick-and-mortar sentences that turned the novel into a mire of high dramatic flourishes, muddying the larger narrative movement of Annis’ journey and her interpersonal interactions. Here’s an example:

“Walking back to the big house, I wade through a high, moon-driven tide; entering its bowels, I submerge myself in a sable lake. I am watching my feet, so I don’t see the lady in the kitchen, white and thin as an unburnt wick. Cora burns brown and tall; she stares at the floor, her hands folded, and it is the first time the room, and everything in it, doesn’t yield to her.”

When did we go from the “sable lake” to the kitchen? Fiction can contract and expand time at will, but this particular passage left me puzzled. Unless the moon-driven tide is a description of the path back to the house, since the previous scene we saw Annis pull herself from a rushing current to a riverbank? Perhaps these are the floodplains? “Moon-driven tide” certainly points to that...okay, I'll imagine she has quickly went from wading in deep water to the kitchen of the plantation owner's house. Now the description of the characters, which is clever—the plantation owner an unburnt wick, the enslaved housekeeper who “burns”—and yet this is immediately doused by the obvious admission that Cora, the slave, is not in charge of this space, these people, her life. The implication is that of willpower and personality, and yet it feels flat due to the novel's diegetic circumstances. Is this really the first, the only, time Cora is standing in the same room as the plantation owner? I’m nitpicking here, which is a huge critical faux pas, but the novel follows this schema to an exhaustive degree. I am swallowed in bombastic detail and metaphor, and there’s only so many “the day before me; a hungry coyote with its jaws open” that Ward can deliver before they begin to dull into each other, flattening her language to noise: a pleasant distraction at best, an irritation at worst.

When I read Sing, Unburied, Sing, I quickly picked up on Ward’s heightened language and found that, at times, it was perhaps a bit too ornamented. Yet the weight of its characters, and the weight of the story it was trying to tell, kept the pages from floating into abstraction and disbelief—to quote the poet Stephen Dunn, “I love abstractions, I love / to give them a nouny place to live.” Let Us Descend lacks that grounding, and felt wholly unrestrained in its outpouring of language. I was left not with the tender ache I know carried Ward through the writing of this story, nor with the triumph of agency that Annis holds by the novel's conclusion—another major departure from Dante, who is largely railroaded by Virgil & Co.—but a feeling of unmoored disbelief, caught between wanting more from the novel’s subjects and also wanting far, far less.

This book is exquisite. The poetry of Ward’s writing blows me away. She’s one of the best to ever do it. A very enthusiastic 5 stars.