You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

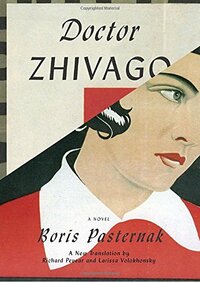

Beautiful, sweeping, haunting and terribly sad, Pasternak’s tragic story of star-crossed love effectively covers his country’s turbulent transition from czarist Russia to the merciless USSR. Far more than a simple tale of lost love, it is a paean to the land he loves, a romance of both town and countryside, embracing the deep-scented forests in equal measure to the rushing dirty cities, the rumor-ridden towns alternatively enriched and then brutally effaced by war, and the trains - by turns racing and choked into stillness - which interlace the landscape, carrying and impeding hopes and dreams.

Hopelessness is as pervasive as beauty, and poetry lingers like a specter over all. This is not a novel to appeal to all sensibilities. Stark realism oscillates with mystical musings, extended philosophical arguments appear faintly ridiculous when exchanged for the grunts and murmurs of nauseous peasants hiding from the authorities under houses. Forget about happy endings. But the language is beautiful, the descriptions of the natural environment often attain to the sublime, and the story emerges intact, even through the vicissitudes of time and translation.

This isn’t a book that should be forced on high school students. Don’t read it under pressure, or for an assignment. It is meant to be savored, not read in a hurry. The pacing is stately, almost ritualistic, like a poem, and lends itself well to short reading spells. Take your time and breathe. You might catch the tang of new-fallen snow over a rowan tree in a silent forest, the howl of a lone wolf outside of an abandoned house, or train exhaust floating over the smoke of a thousand chimneys. Heave a sigh, sip some tea (strong-brewed Russian Caravan), and then continue.

Hopelessness is as pervasive as beauty, and poetry lingers like a specter over all. This is not a novel to appeal to all sensibilities. Stark realism oscillates with mystical musings, extended philosophical arguments appear faintly ridiculous when exchanged for the grunts and murmurs of nauseous peasants hiding from the authorities under houses. Forget about happy endings. But the language is beautiful, the descriptions of the natural environment often attain to the sublime, and the story emerges intact, even through the vicissitudes of time and translation.

This isn’t a book that should be forced on high school students. Don’t read it under pressure, or for an assignment. It is meant to be savored, not read in a hurry. The pacing is stately, almost ritualistic, like a poem, and lends itself well to short reading spells. Take your time and breathe. You might catch the tang of new-fallen snow over a rowan tree in a silent forest, the howl of a lone wolf outside of an abandoned house, or train exhaust floating over the smoke of a thousand chimneys. Heave a sigh, sip some tea (strong-brewed Russian Caravan), and then continue.

challenging

dark

emotional

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Bless the endless Russian winter... but sometimes it just goes on and on and gives too much time for the Russian writer. Sigh.

I tried so hard to like this book. It took me until "Part Seven" to start getting into it, and I thought my interests had turned towards the light in "Book Two," but I was wrong. This is an incredibly slow story, and my desire to read it never reached a peak. I own it, so perhaps I'll finish it one day, but there are others I'd rather be reading right now.

This book is so much more than an epic historical love story, but I would never have picked up on it earlier in life. It is a Russian philosophical feast. The women in Zhivago's life clearly portray his feelings about Russia and the social changes that it went through. I'm amazed at how Pasternak was able to do this. The audio version was excellent because it provided a short intro that helped me with the magical /folktale part of the book, and then it had an afterword and a short history on Pasternak's life. Just be prepared for its typical Russian length and repetitiveness on theme / thought. Oh, and the love story is magnificent, too.

One of my favorite scene in the book that will stay with me was when Dr. Zhivago is captured by a red army unit and finds himself in an engagement with them and a white army unit that is trying to flank them. Zhivago (who is a medic and not trusted with a weapon) has nothing else to do but lay low on the ground be a spectator. His conscience starts eating him up though and he feels wrong for just being a spectator as young men are dying so he grabs the weapon of someone lying next to him who is already dead. Zhivago tries to shoot at the white army soldiers but he isn't able to muster up the courage to do so as he sympathies with them as much as his own men. As a result he starts shooting at a small tree but one of the rounds does end up hitting and killing a white army soldier. After the engagement Zhivago sees the young man is still alive and nurses him back to health (lying to his men that he is a newly conscripted red army soldier). Later Zhivago lets him go knowing full well that the young man is going back to fight for the white army. It's a great example of the constant war inside Zhivago between his humanity and his duties. The book shows us the dystopian nightmare that man is capable of creating in this world but also man's firm resolve to not despair in his circumstances, to always hope and to act- as Pasternak puts it.

dark

reflective

sad

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

N/A

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

Under the old order, which enabled those whose lives were secure to play the fools and eccentrics at the expense of the others while the majority led a wretched existence, it had been only too easy to mistake the foolishness and idleness of a privileged minority for genuine character and originality.If you're in any way interested in delving into "Western"/Euro + Neo Euro literature, be prepared for tons of Bible fanfiction. Some of it's pretty decent, like 'Paradise Lost'. Others attempt to be just as epic as its source material with uneven results, such as 'Joseph and His Brothers'. Still others read as if the author managed to inject the King James translation straight into their veins à la 'Moby Dick', and I'm sure the as of yet unread 'East of Eden' has its own singular contributions to make. But sometimes, you get something like this: a main character who, upon taking a glance at the modern United States, would probably blame the social unrest on Jewish millionaires and bemoan the nationwide oppression of white Christians, seeing as how the narrative uncritically casts him as a new Jesus figure and the child abuse survivor that he cheated on his wife with (and then cheated on in turn) as Mary Magdalene. Now, I usually don't care what roleplaying contortions the average author puts their characters; indeed, my constantly cross-referencing brain usually delights in ferreting out such subtle interplays that, at their best, both enhance an already venerable complexity and generate a novel masterpiece. However, Pasternak is far more interested in telling you of the ingenious marvels of his characters, themes, and love story than actually proving their right to be called such, and when such straightforward dictation is coupled with roiling antisemitism spewed out from the thoughts and mouths of both his beloved, starstruck lovers, it becomes little short of absolutely pathetic.

"...Incidentally, if you do intellectual work of any kind and live in a town, as we do, half of your friends are bound to be Jews...It's so strange that these people who once liberated mankind from the yoke of idolatry, and so many of whom now devote themselves to its liberation from injustice, should be incapable of liberating themselves from their loyalty to an obsolete, antediluvian identity that has lost all meaning, that they should not rise above themselves and dissolve among all the rest whose religion they have founded and who would be so close to them, if they knew them better.["]That's the Magdalene figure agreeably conversing with the Jesus figure for you and the death knell of this narrative's credibility for me. See, after running into an entire page of a similarly themed digression on Zhivago's part a hundred pages in wherein he called Jewish people an army that brought its agonies on its own head through holding on to their own identity and refusing to dissolve into Christianity, I voiced my trepidation. However, I was willing to keep going to see whether this message was in any way complicated, critiqued, or at least developed into something more interesting than that, if for no other reasons than Pasternak's Jewish heritage and my own commitment to finishing any work begun on this site. A hundred fifty pages later, I had run into nothing of the positive sort before hitting this blowhard chunk, after which I had little hope of doing anything more than trudging through the rest of it. Yes, diabolical historical events and multitudes of characters and dramatic narratives flung across sizable quantities of space and time, but if Yurii Andreievich Zhivago had just submitted to the majority ruled regime and gave up all his culture, ideologies, and heritage in order to fit in, he would have been just fine. Oh, was there a fear of recrimination no matter how much you hid your spots? Oh, are the Powers That Be building up kyriarchical systems that are uncannily zeroed in on you and your loved ones? Oh, do you draw strength a tad too much beliefs whose ancestral transcribers stretch back hundreds, if not thousands, of years to give it up entirely? If only there were a group who had enormous amounts of experience with such, with many members who have been present on the side of those fighting for their rights on many a historical plane. Oh. Wait.

"Of course it's true that persecution forces them into this futile and disastrous attitude, this shamefaced, self-denying isolation that brings them nothing but misfortune. But I think some of it also comes from a kind of inner senility, a historical centuries-long weariness. I don't like their ironical whistling in the dark, their prosaic, limited outlook, the timidity of their imagination. It's as irritation as old men talking of old age or sick people about sickness. Don't you think so?"

When at the beginning of the revolution it had been feared that, as in 1905, the upheaval would be a short-lived episode in the history of the educated upper classes and leave the deeper layers of society untouched, everything possible had been done to spread revolutionary propaganda among the people to upset them, to stir them up and lash them into fury.After reading Goldman's [b:Living My Life, Vol. 2|27699|Living My Life, Vol. 2|Emma Goldman|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1328865566l/27699._SY75_.jpg|15340500], it's impossible to defend what the Russian Revolution eventually became long before Lenin met his end. What I take issue with is how snidely this narrative mimics Trump in blaming the movement's initially righteous protest on "degenerate" (a fascist dogwhistle for anyone "memeing" these days), "anti-social" elements, as well as its absolutely baffling proclamation for Jewish people to erase themselves in the wake of the Holocaust. Now, it's easy to chalk this stance of mine up to my not having fond memories of any of the films, as well as the general fact of much of my sentiment being burned out of me a long time ago. Still, the flat characters that made tracking rather pointless the further the narrative moved from its bildungsroman beginnings, the repetitious dictation of how the reader should be thinking at such and such a time, the less and less credible glorification of a character who is so eager to pass judgment and so divested from the life that anarchists and socialists sought to figure out for the sake of all: the narrative was best in its descriptions of nature and extremely tedious outside of that. The usual comments about poor translations can be made, and I really did like Larisa/Lara Feodorovna Guishar in her initial incarnation, much as I felt generally favorable about others in their younger years, but this is not a work that needs my revisiting decades down the line. It was a good lesson, at any rate, when it comes to reading for the sake of diversity. The more popularly uplifted and classically lauded a work, the harder it is to tell when an author has something to prove.

In those early days, men like Pamphil Palykh, who needed no encouragement to hate intellectuals, officers, and gentry with a savage hatred, were regarded by enthusiastic left-wing intellectuals as a rare find and greatly valued....

...To Yurii Andreievich this gloomy and unsociable giant, soulless and narrow-minded, seemed subnormal, almost a degenerate.

"How splendid, " she thought, listening to the gun shots. "Blessed are the downtrodden. Blessed are the deceived. God speed you, bullets. You and I are of one mind."A nicely stirring quote. Too bad the rest of the work didn't follow in its footsteps.

A wonderful book. Undoubtedly the second part is better than the first, however overall, I think this is one of the few occasions where the film is better than the book. It could be that the translation (Hayward & Harari) wasn't the best. Overall I enjoyed it, and it certainly filled in the gaps of the incredible film.

"Even more than by what they had in common, they were united by what separated them from the rest of the world. They were both equally repelled by what was tragically typical of modern man, his shrill textbook admirations, his forced enthusiasm, and the deadly dullness conscientiously preached and practised by countless workers in the field of art and science in order that genius should remain extremely rare." P.355

"Even more than by what they had in common, they were united by what separated them from the rest of the world. They were both equally repelled by what was tragically typical of modern man, his shrill textbook admirations, his forced enthusiasm, and the deadly dullness conscientiously preached and practised by countless workers in the field of art and science in order that genius should remain extremely rare." P.355

I’m usually not one to not finish a book, but I gave this one until page 136 out of some 500 pages to try to win me over, in the end I just couldn’t do it. The multiple names for one person was extremely confusing, and I couldn’t keep track of what year it was or what historical events were happening that they were referring to. It was hard to even care remotely about the characters, none of them seemed like able. I’m not even sorry for not finishing this book, at least I tried. Just not for me