Take a photo of a barcode or cover

First off, this book is great and Helen Oyeyemi is amazing, and I recommend reading this without reservation. It's so good and different and magical and I really loved it.

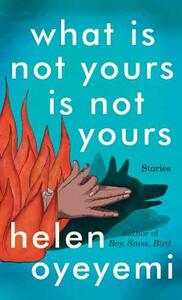

But it also marked the 2nd time in like, 2 years for me where I went into a book of short stories thinking it was a novel. And it made sense for so much of the book (some repeating characters and themes) but then it just really really didn't. I was so eager to see how this sprawling world was gonna come together in a tidy single narrative package, but then started to question whether it would. So I flipped back to the cover and yeah... "stories" is right in the title. Duh.

I dunno what the lesson is here, but I probably have to re-read this again, and I don't mind at all.

But it also marked the 2nd time in like, 2 years for me where I went into a book of short stories thinking it was a novel. And it made sense for so much of the book (some repeating characters and themes) but then it just really really didn't. I was so eager to see how this sprawling world was gonna come together in a tidy single narrative package, but then started to question whether it would. So I flipped back to the cover and yeah... "stories" is right in the title. Duh.

I dunno what the lesson is here, but I probably have to re-read this again, and I don't mind at all.

The title of this book pretty aptly sums up how I felt reading these stories - a distant observer trying to puzzle out what was happening in these at turns mundane but also often fantastical interrelated stories that in no way belong to me.

I always have a hard time reviewing short stories and essay compilations because I usually walk away confused and disoriented by what I just read. I don't know if that's just the nature of this writing format or of the authors I tend to select to read.

So, I'm going to rely on snippets of the reviews on the jacket of the book as they describe this book better than I ever could and then share some quotes that stuck out to me.

"Gloriously unsettling", "gently perverse", "frighteningly strange", "glimmers with pixie dust". My descriptive words in my notes were "surreal but with the feel of folklore and an element of mundanity".

Quotes:

"as they came to understand each other they learned that what they'd been afraid of was running out of self. On the contrary the more they loved the more there was to love."

"I don't feel one hundred percent sure I'm not a puppet myself"

"Instead they turned motion and intelligible speech into a currency with which personhood is earned"

P.s. "fans" of Johnny Depp should read the second story

I always have a hard time reviewing short stories and essay compilations because I usually walk away confused and disoriented by what I just read. I don't know if that's just the nature of this writing format or of the authors I tend to select to read.

So, I'm going to rely on snippets of the reviews on the jacket of the book as they describe this book better than I ever could and then share some quotes that stuck out to me.

"Gloriously unsettling", "gently perverse", "frighteningly strange", "glimmers with pixie dust". My descriptive words in my notes were "surreal but with the feel of folklore and an element of mundanity".

Quotes:

"as they came to understand each other they learned that what they'd been afraid of was running out of self. On the contrary the more they loved the more there was to love."

"I don't feel one hundred percent sure I'm not a puppet myself"

"Instead they turned motion and intelligible speech into a currency with which personhood is earned"

P.s. "fans" of Johnny Depp should read the second story

Struggled with this one. Quite a lot. I liked the ideas presented in each story, but the execution fell short. I was put off by the way a story would begin in one direction, then ramble on a bit in another, then throw the initial story line back at you. It mostly left me thinking, "Wait - what, now?" This collection of short stories feels like some modern art to me; like it's intention was to make you feel dumb if you don't "get" it. I genuinely like the touches of magical realism, and there were peeks at genius in a few lines, but overall my feelings are - at best - luke warm, bordering on tepid.

adventurous

funny

mysterious

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Loveable characters:

Yes

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Mum and Dad wouldn’t be thrilled by my new career ambitions. Don’t forget your Uncle Majhi… Majhi the mime… and ask yourself, do we really want more people like that in our family? My parents worked a lot—no need to bother them with something that might not work out. The thing to do was gain admission first and talk them round later. I bought a brown-skinned glove puppet. He came with a little black briefcase and his hair was parted exactly down the middle. The precision of his parting made me uneasy; somehow it was too human at the exact same time as exposing his status as a nonhuman. I got him a top hat so I wouldn’t have to think about the cloth hair falling away from the center of his cloth scalp. You gave me a hand with some basics of ventriloquism, even though you definitely weren’t supposed to help—it was then that I began to hope that you’d stop saying I wasn’t right for you—and I taught my puppet to tell jokes with a pained and forlorn air, fully aware of how bad the jokes were. Sometimes you laughed, and then my glove puppet would weep piteously. When you took the glove puppet he alternated between flirtatious and suicidal, hell-bent on flinging himself from great heights and out of windows. I noticed that you didn’t make a voice or a history for the puppet, but you became its voice and history. I’d have liked to admire that but felt I was watching a distressing form of theft, since the puppet could do nothing but suffer being forced open like an oyster.

***

Her first short fiction collection following five novels and two plays, Helen Oyeyemi’s What is Not Your is Not Yours is a bit difficult to get a feel for—at once quite intelligent and decidedly well written, it’s also detached, its characters and plots for the most part removed from one another, at least on an emotional level.

The nine stories in the collection all revolve around or contain some reference to a key of one sort or another. Characters occasionally exist in multiple stories, and threads of connectivity do exist, but the stories are primarily independent of one another, save this shared conceit.

In “Books and Roses,” a young girl named Montserrat is abandoned with a key around her neck, the purpose of which remains for years a mystery. She comes to befriend another woman with a key of her own, an artist awaiting the return of her possibly murderous lover. “Sorry Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea” begins by discussing the narrator’s friendship with a man named Chedorlaomer, and then diverges into its primary tale about a violent, ill-tempered musician named Matyas Füst who abuses a prostitute, and when knowledge of this goes viral, proceeds to fumble his apology—and then continues to fumble the apology to his apology in much the same way, by focusing entirely on himself and not at all on the individual he hurt.

With the DNA of Pinocchio at its core, “Is Your Blood as Red as This?” is a story about puppeteers and students of puppetry, with a shifting narrative voice: the first half belongs to Radha; the second to her living puppet Gepetta. In “Drownings,” a man named Arkady plots to kidnap the daughter of the tyrant who orphaned him, having his parents drowned in the middle of the night when he was just a boy.

“Presence,” one of the collection’s strongest entries, follows a couple as they undergo a psychological experiment charting their presences, and the possibilities inherent to their lives and futures, when not in the same location. In an interesting turn of events, and as one of the more affecting sequences in the entire book, the wife, Jill, goes so far as to hallucinate, in a very believable way, a son that never existed in the first place. The experience is described intriguingly as “an implosion of memory. And as the subjects drift through the subsequent debris, they calmly develop a conviction that they do not do so alone.”

“A Brief History of the Homely Wench Society” explores two university societies as they go head-to-head with one another while issues of interpersonal love and lust go unabated. “Dornicka and the St. Martin’s Day Goose” is another entry obviously influenced by fairy tales, imagining if Red Riding Hood were older, wiser, widowed, and had struck a deal with the Big Bad Wolf—to find for him a sacrifice rather than to allow him to feast on just any unfortunate passerby. A charming story about things from youth being locked away, to be sacrificed or bargained for in adulthood. It’s in this and the first story that the use of the key as a narrative device works best.

“Freddy Barrandov Checks . . . In?” introduces us to the titular nursery school teacher, the son of two Hotel Glissando employees who wish their offspring to follow in their footsteps—whether it’s what he wants or not. And lastly, “If a Book is Locked There’s Probably a Good Reason for That Don’t You Think” dives deep into office gossip subculture as a new employee—Eva—is at first idolized for her mystery and appearance, and then ostracized for being an adulterer. She carries with her a diary she’d stopped writing in years earlier—the story’s lock in need of a key, of course.

While I loved the mystery of the final story’s ending, and how it felt somehow complete in its ambiguity, that’s more than I can say for many others in this collection. Which, I suppose, is one of my chief complaints: that the majority of the stories don’t feel so much as they end as they limp off into the distance having been shot in the calf.

The second issue I have with this collection is with respect to the key, both as an object and a theme that runs throughout. Frequently the presence of these keys felt unnaturally forced into place in each story. I was made aware of the conceit of the key prior to reading this book, upon reading an interview given by the author. I can’t be sure had I not known about its purpose ahead of time that the sense of discovering a key in each story might have been stronger, but going into the collection with this knowledge in mind, I think, helped to draw additional attention to their existence—an unfortunate thing in this instance, as they routinely stood out as items injected into scenes not always necessary to the whole, as if the author had decided upon the shared imagery after the fact.

Lastly, I have to admit I struggled with the nested aspect of many of these tales. Oyeyemi’s short stories are like Matryoshka dolls that begin with an outer layer not necessarily linked—at least not intrinsically—to what’s inside; often I felt as if I was being taken on tangents too many to count, and as such found myself not necessarily losing focus but certainly losing interest in the “main” narratives of several of the stories. However, this is a personal issue. I am pickier about short fiction than I am any other form, and what I often like most about the works of short fiction that have stuck with me over time is their focus—the promise of a single idea stretched and spiralled to its limit. Oyeyemi’s short stories, on the other hand, meander and take their time finding their way to the end. I can’t really fault this as it is a stylistic decision, and a valid one at that, but in this format it did not work for me, and I was left at the end of each story feeling more frustrated than not.

On a purely technical level, Oyeyemi’s craft is second to none. Her use of language is skilful as always, and her abilities only seem to increase with each book. Narratively, though, I flip-flop on her work, and often come down on the side of wanting to love it so much more than I actually do. To date, I’ve read four of her novels, and her first, The Icarus Girl, is still my favourite, with the wickedly constructed White is for Witching a close second; Mr. Fox failed to connect with me, and though I found the writing in Boy, Snow, Bird to be exceptional, its narrative fell apart for me in its final section.

Given my issues with the narrative structure of many of the stories in this collection, I can’t wholeheartedly recommend it, though I would likely still place it in the middle of the pack—it doesn’t reach the heights of Icarus and Witching, but it’s an interesting work all the same. I only wish I could say I enjoyed it more than I did, but the best I can offer is a tepid shrug and a recommendation for maybe three or four of the nine stories: “Presence,” “Dornicka and the St. Martin’s Day Goose,” “Drownings,” and “If a Book is Locked There’s Probably a Good Reason for That Don’t You Think.” And of these, “Presence” and “Drownings” were the only two I felt successfully established any sort of emotional connection. Which means either I’m dead inside, or perhaps this collection just wasn’t right for me.

Crossing my fingers for the latter.

***

Her first short fiction collection following five novels and two plays, Helen Oyeyemi’s What is Not Your is Not Yours is a bit difficult to get a feel for—at once quite intelligent and decidedly well written, it’s also detached, its characters and plots for the most part removed from one another, at least on an emotional level.

The nine stories in the collection all revolve around or contain some reference to a key of one sort or another. Characters occasionally exist in multiple stories, and threads of connectivity do exist, but the stories are primarily independent of one another, save this shared conceit.

In “Books and Roses,” a young girl named Montserrat is abandoned with a key around her neck, the purpose of which remains for years a mystery. She comes to befriend another woman with a key of her own, an artist awaiting the return of her possibly murderous lover. “Sorry Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea” begins by discussing the narrator’s friendship with a man named Chedorlaomer, and then diverges into its primary tale about a violent, ill-tempered musician named Matyas Füst who abuses a prostitute, and when knowledge of this goes viral, proceeds to fumble his apology—and then continues to fumble the apology to his apology in much the same way, by focusing entirely on himself and not at all on the individual he hurt.

With the DNA of Pinocchio at its core, “Is Your Blood as Red as This?” is a story about puppeteers and students of puppetry, with a shifting narrative voice: the first half belongs to Radha; the second to her living puppet Gepetta. In “Drownings,” a man named Arkady plots to kidnap the daughter of the tyrant who orphaned him, having his parents drowned in the middle of the night when he was just a boy.

“Presence,” one of the collection’s strongest entries, follows a couple as they undergo a psychological experiment charting their presences, and the possibilities inherent to their lives and futures, when not in the same location. In an interesting turn of events, and as one of the more affecting sequences in the entire book, the wife, Jill, goes so far as to hallucinate, in a very believable way, a son that never existed in the first place. The experience is described intriguingly as “an implosion of memory. And as the subjects drift through the subsequent debris, they calmly develop a conviction that they do not do so alone.”

“A Brief History of the Homely Wench Society” explores two university societies as they go head-to-head with one another while issues of interpersonal love and lust go unabated. “Dornicka and the St. Martin’s Day Goose” is another entry obviously influenced by fairy tales, imagining if Red Riding Hood were older, wiser, widowed, and had struck a deal with the Big Bad Wolf—to find for him a sacrifice rather than to allow him to feast on just any unfortunate passerby. A charming story about things from youth being locked away, to be sacrificed or bargained for in adulthood. It’s in this and the first story that the use of the key as a narrative device works best.

“Freddy Barrandov Checks . . . In?” introduces us to the titular nursery school teacher, the son of two Hotel Glissando employees who wish their offspring to follow in their footsteps—whether it’s what he wants or not. And lastly, “If a Book is Locked There’s Probably a Good Reason for That Don’t You Think” dives deep into office gossip subculture as a new employee—Eva—is at first idolized for her mystery and appearance, and then ostracized for being an adulterer. She carries with her a diary she’d stopped writing in years earlier—the story’s lock in need of a key, of course.

While I loved the mystery of the final story’s ending, and how it felt somehow complete in its ambiguity, that’s more than I can say for many others in this collection. Which, I suppose, is one of my chief complaints: that the majority of the stories don’t feel so much as they end as they limp off into the distance having been shot in the calf.

The second issue I have with this collection is with respect to the key, both as an object and a theme that runs throughout. Frequently the presence of these keys felt unnaturally forced into place in each story. I was made aware of the conceit of the key prior to reading this book, upon reading an interview given by the author. I can’t be sure had I not known about its purpose ahead of time that the sense of discovering a key in each story might have been stronger, but going into the collection with this knowledge in mind, I think, helped to draw additional attention to their existence—an unfortunate thing in this instance, as they routinely stood out as items injected into scenes not always necessary to the whole, as if the author had decided upon the shared imagery after the fact.

Lastly, I have to admit I struggled with the nested aspect of many of these tales. Oyeyemi’s short stories are like Matryoshka dolls that begin with an outer layer not necessarily linked—at least not intrinsically—to what’s inside; often I felt as if I was being taken on tangents too many to count, and as such found myself not necessarily losing focus but certainly losing interest in the “main” narratives of several of the stories. However, this is a personal issue. I am pickier about short fiction than I am any other form, and what I often like most about the works of short fiction that have stuck with me over time is their focus—the promise of a single idea stretched and spiralled to its limit. Oyeyemi’s short stories, on the other hand, meander and take their time finding their way to the end. I can’t really fault this as it is a stylistic decision, and a valid one at that, but in this format it did not work for me, and I was left at the end of each story feeling more frustrated than not.

On a purely technical level, Oyeyemi’s craft is second to none. Her use of language is skilful as always, and her abilities only seem to increase with each book. Narratively, though, I flip-flop on her work, and often come down on the side of wanting to love it so much more than I actually do. To date, I’ve read four of her novels, and her first, The Icarus Girl, is still my favourite, with the wickedly constructed White is for Witching a close second; Mr. Fox failed to connect with me, and though I found the writing in Boy, Snow, Bird to be exceptional, its narrative fell apart for me in its final section.

Given my issues with the narrative structure of many of the stories in this collection, I can’t wholeheartedly recommend it, though I would likely still place it in the middle of the pack—it doesn’t reach the heights of Icarus and Witching, but it’s an interesting work all the same. I only wish I could say I enjoyed it more than I did, but the best I can offer is a tepid shrug and a recommendation for maybe three or four of the nine stories: “Presence,” “Dornicka and the St. Martin’s Day Goose,” “Drownings,” and “If a Book is Locked There’s Probably a Good Reason for That Don’t You Think.” And of these, “Presence” and “Drownings” were the only two I felt successfully established any sort of emotional connection. Which means either I’m dead inside, or perhaps this collection just wasn’t right for me.

Crossing my fingers for the latter.

challenging

mysterious

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

N/A

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

Just honestly not sure what any of it means

A key ring gets left in your care and you reject all responsibility for it yet can't bring yourself to throw it away. Nor can you give the thing away -- to whom can someone of good conscience give such an object as a key? Always up to something, stitching paths and gateways together even as it sits quite still; its powers of interference can only be guessed at. (is your blood as red as this?, p. 144)

La prose glissante d'Oyeyemi est un plaisir parfois coriace, souvent lumineux, toujours surprenant. Ici, ses nouvelles jonglent avec quelques personnages récurrents, font tinter les clés qui dorment dans leurs poches, rient à gorge déployée & réussissent à tisser des mondes qui, sans toujours être directement liés entre eux, participent d'une même logique étrange, inquiétante, absurde & souveraine.

Même si j'ai trouvé pénibles les incursions dans l'univers des marionnettistes (mon doux seigneur préservez-moi de métaphores boiteuses du type qui tire vraiment les ficelles de votre vie, chère lectrice?), tout le reste m'a énormément plu. J'ai relu certaines nouvelles tout de suite après les avoir terminées, parce qu'Oyeyemi offre rarement des réponses claires aux questions soulevées par ses intrigues ; on pourrait dire qu'elle fait confiance à la lectrice, mais je pense plus qu'elle s'amuse, très simplement. Elle cache des bouts de sens dans ses phrases & en fait une chasse aux trésors. C'est d'une espièglerie parfaite, & d'une ambition qui n'a pas peur du chambranlant.

adventurous

dark

emotional

funny

mysterious

relaxing

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Complicated

I absolutely loved this book and am excited to read more from the author. I'm a sucker for short story collections that take bits and pieces of the characters and narratives to cross foster in different stories.

books and roses - 5/5

"sorry" doesn't sweeten her tea - 4.5/5

is your blood as red as this? - 3/5

drownings - 4/5

presence - 4/5

a brief history of the homely wench society - 3.5/5

dornička and the st. martin's day goose - 3.5/5

freddy barrandov checks...in? - 3/5

if a book is locked there's probably a good reason for that don't you think - 3.5/5

She exchanged two Edith Wharton novels for two Henry James novels, Lucia Berlin's short stories for John Cheever's, Elaine Dundy's The Dud Avocado for Dany Laferrière's I Am a Japanese Writer, Dubravka Ugresic's Lend Me Your Character4.5/5

for Gogol's How the Two Ivans Quarreled and Other Stories, Maggie Nelson's Jane: A Murder for Capote's In Cold Blood, Lisa Tuttle's The Pillow Friend for The Collected Ghost Stories of M. R. James.

This isn't the first Advanced Readers Copy (ARC) I've reviewed on this site, but I feel more of a need to make a distinction here, seeing as how Oyeyemi's slippery prose would naturally be even slipperier in an unfinalized form, especially seeing as how I intend to quote. I didn't care enough about avoiding this quandary to wait on till I ferreted out a non-ARC at a successive sale, and care even less about planning a future reread once they become more common, so it's a good thing that Oyeyemi's style favors the crossroads. Admittedly, there were a few grammar errors that I'm sure didn't conscientiously fall under the purview of either experimental fantasy or fantastical experimentation, but I'm not drawing my copied out material from those realms anyway, so I'll leave those for others to mess around in.

I've a special love for short stories that take on the challenge of short story cycles, as the largest worlds are always made by selective omission, acknowledging brief flutters of connection but never restricting the reader's own choice in how to interpret these references flung across the void. I've an even more special love for fantasy, and intimations of culture outside the WASPing norm, and queer romance, so while if someone calculates the average of the short stories above and observes that it is lower than 4.5, this work is indeed a prime example of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. While it's true that the rapid pace and strategic lack of detail frustrated the paces, I found the efficient touches of blatantly ethnic names amidst the changing paces of blunt domesticity and All the Better To Eat You, My Dear, more believable than the most expansively Victorian lists of descriptive force that attempted to capture every aspect of a global clime but the spark of humanity: in other words, the only thing that mattered. I didn't get as much of [b:Mr. Fox|10335337|Mr. Fox|Helen Oyeyemi|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1313998352s/10335337.jpg|15237931]'s incisive dagger to the heart of the normalization of misogynistic violence as I'd like, but '"sorry" doesn't sweeten her tea' had such a nice twist of it that I was satisfied (the jury is still out on that story due to fetishization of both the sex work and the sanity variety, but I wouldn't mind writing an essay on it all). For the short stories with lower ratings, it was more often than not a matter of too much give and not enough grip, the story ending before I had plucked something from it in any meaningful sense or hooked it in with the rest of the cycle, leaving me with the faint nausea that is manic pixie dream in excess. I still left the book with a feeling of completeness, though, so the first and best story won out in the end.

I hold by a previous status that made a promise to pick up any and all copies of as of yet unread Oyeyemi's works. She's too interesting, both as a person and as a writer, to indulge in as intermittently and infrequently as I have been doing thus far. This is especially the case now when Gaiman (a spiritual ancestor, if flawed, to this work if there ever was one) is getting his time in the visual spotlight, as any and all of Oyeyemi's works I've encountered thus far would be a golden opportunity for any up and coming animator/actor/soundtrack composer/etc to try their creative hand at. I can't imagine that her developing in worthwhile writerly ways will result in any higher GR ratings for her future works, but it's a joy that this doesn't seem to be much of an issue. I can only eagerly wait for what comes.

Even though all went on as before, Mum's developed a sort of prejudice against writers; there are behaviors she now calls "writerly," but I think she actually means uncooperative.

I was lukewarm about essentially every story in this book. :(