You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

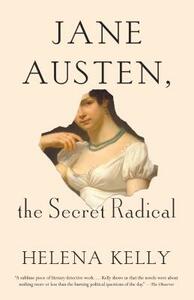

While Helena Kelly surely knows how to write nonfiction, I can't get past of her interpretations of Jane Austen's novels. Kelly has a point of view that is highly anachronistic and far fetched at many points. She has surely done her research; when it comes to the contemporaries of Austen and the historical background, Kelly comes across as a good scholar. However I am so frustrated by everything else in this one, including how it seems that Kelly thinks her interpretation is only point of view that matters.

*I received this book for free through Goodreads Giveaways*

This is really a 2.5 star book.

It may be a bit presumptuous for the author to claim that she is presenting Jane Austen and her works as "[Jane] wanted to be read", especially considering the tear-down Kelly presents of Austen's family's portrayal of her but the concept is enticing, namely that Jane Austen's works were well-disguised criticisms of her contemporary society and not just drawing room romances. Also, even though the order of the "critical readings" is supposedly in the order they were made ready for publication, it could also--considering how Austen's works and Austen herself are typically viewed--be seen as in increasing likelihood of main character(s) ending up as spinster(s).

Also it's a bit confusing -- and comes off a bit like too much like trying to be "in" or "down" -- that the author constantly refers to Austen as "Jane" and not by her last name. It feels like the author is trying to impress how well she knows "Jane", enough to be on a first name basis and that she is closer to her and to understanding her than all those other writers who use "Austen". Furthermore, since Austen used the name "Jane" herself for several of the characters in her books, and since this book is about a way of reading those books, certainly the characters' names come up many times throughout the book, including Jane. This is especially confusing (read: annoying) in the chapter about [b:Pride and Prejudice|1885|Pride and Prejudice|Jane Austen|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1320399351s/1885.jpg|3060926] since the secondary female character is named Jane -- I'm never sure whether the author of this book is referring to that Jane or to Austen herself and I often have to go back and reread a sentence because I'm left confused, having thought we referring to the former when really it was the latter.

I'm not sure I agree with Kelly's readings of Austen's novels although her reading of [b:Mansfield Park|45032|Mansfield Park|Jane Austen|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1397063295s/45032.jpg|2722329] is somewhat convincing, helped in no small part by the fact that the maker's of the 1999 film adaptation seemed to wholeheartedly share the view that the book is about or at least heavily referencing slavery. However, some of the others feel a bit stretching, especially the last one about [b:Persuasion|2156|Persuasion|Jane Austen|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1385172413s/2156.jpg|2534720]; it almost feels like the author didn't originally have an alternative reading in mind for Persuasion but since all the other books had one, they came up with one quickly even if the amount of evidence for it feels decidedly lacking compared to some of the others. Overall, I agree only with the very ending of this book: read Jane Austen's works again.

This is really a 2.5 star book.

It may be a bit presumptuous for the author to claim that she is presenting Jane Austen and her works as "[Jane] wanted to be read", especially considering the tear-down Kelly presents of Austen's family's portrayal of her but the concept is enticing, namely that Jane Austen's works were well-disguised criticisms of her contemporary society and not just drawing room romances. Also, even though the order of the "critical readings" is supposedly in the order they were made ready for publication, it could also--considering how Austen's works and Austen herself are typically viewed--be seen as in increasing likelihood of main character(s) ending up as spinster(s).

Also it's a bit confusing -- and comes off a bit like too much like trying to be "in" or "down" -- that the author constantly refers to Austen as "Jane" and not by her last name. It feels like the author is trying to impress how well she knows "Jane", enough to be on a first name basis and that she is closer to her and to understanding her than all those other writers who use "Austen". Furthermore, since Austen used the name "Jane" herself for several of the characters in her books, and since this book is about a way of reading those books, certainly the characters' names come up many times throughout the book, including Jane. This is especially confusing (read: annoying) in the chapter about [b:Pride and Prejudice|1885|Pride and Prejudice|Jane Austen|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1320399351s/1885.jpg|3060926] since the secondary female character is named Jane -- I'm never sure whether the author of this book is referring to that Jane or to Austen herself and I often have to go back and reread a sentence because I'm left confused, having thought we referring to the former when really it was the latter.

I'm not sure I agree with Kelly's readings of Austen's novels although her reading of [b:Mansfield Park|45032|Mansfield Park|Jane Austen|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1397063295s/45032.jpg|2722329] is somewhat convincing, helped in no small part by the fact that the maker's of the 1999 film adaptation seemed to wholeheartedly share the view that the book is about or at least heavily referencing slavery. However, some of the others feel a bit stretching, especially the last one about [b:Persuasion|2156|Persuasion|Jane Austen|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1385172413s/2156.jpg|2534720]; it almost feels like the author didn't originally have an alternative reading in mind for Persuasion but since all the other books had one, they came up with one quickly even if the amount of evidence for it feels decidedly lacking compared to some of the others. Overall, I agree only with the very ending of this book: read Jane Austen's works again.

Some of the author's analysis feels like a stretch and the narrative bits are completely unnecessary, but overall I was fascinated by the placement of Jane's novels in their historical and personal context and loved the strong, consistent message to appreciate her work as great literature, not old-timey fluff.

I enjoyed this a lot. It was fun to see well known stories take on new meaning through historical context and analysis. I can't say I agree with every conclusion but I really enjoyed it all the same. I can see myself going back and rereading chapters as I do a reread of the various books. Recommend if you are a Jane Austen fan looking for a different persepective.

This book has an interesting premise - Austen was radical and political, unlike the way she has been generally presented and seen as.

The publishers seem to suggest that this is the first book of its kind, but if one delves into the literature on Austen, there is a multitude of articles and books that focus on her political opinions and the way the novels captivate this.

The introduction was structured interestingly, as it opens from Austen’s perspective, but in the third person. Tracing how Austen’s image has been built over time was a good way of establishing the argument within certain contexts.

‘Northanger Abbey’ was written about somewhat disparagingly at points, especially in the opening of the chapter - I have many friends who love this novel and Catherine!

Her exploration of references to pregnancy was interesting, and not a topic I had much considered in the context of Austen. However, I do feel there are other radical aspects that have been missed, such as her mocking of prescriptive literature about female behaviour.

In the chapter on ‘Sense and Sensibility’, the discussion of inheritance and the role of women in the home and the family was interesting. However, beyond this the author seems to be searching for something perverse, and, in my opinion, reads in symbolism that isn’t there - particularly with regards to the behaviours of Edward Ferrars. Beyond this, there are some leaps in logic when it comes to discussions about Colonel Brandon and questions about names within the novel. I wasn’t really convinced by the arguments within this chapter.

Her focus on the militia within ‘Pride and Prejudice’ was very interesting and she addressed things I had not considered before, such as the militia being a disruptive presence throughout the novel. The passages on Mr Collins were very entertaining as he is just absurd. I also particularly enjoyed the section on introductions and the politics of these within the era that Austen was writing. I also liked her discussion of the radical natures of Lizzy and Darcy, and how well matched they are, as it sung to the romantic in me. This chapter was more engaging and seemed to be better grounded in the primary material in its readings of Austen.

The ‘Mansfield Park’ chapter is very interesting, particularly with regards to slavery and the experiences that Austen would have known about and been linked to during her life. The associations made between character names and real life people provided insights that I was unaware of before reading this. Her argument regarding the connections between the church and slavery was well researched and grounded in the text. It had never occurred to me before how unsatisfactory the ending is for Fanny, as Edmund is not a true hero or a particularly great man. I think I need to revisit this novel and reassess!

The chapter on ‘Emma’ begins with rather a lot of preamble regarding enclosures. The information was rather interesting, but I am a history student who has previously studied this topic and has some background knowledge. I’m unsure how useful it all is for those who are just curious to hear about the political nature of ‘Emma’. Enclosures in ‘Emma’ is not a theme I had ever picked up on whilst reading it, as I had not looked this closely. Kelly’s arguments are good on this topic and reveal a different side to the novel to what I had previously seen.

I was slightly upset by her questioning of Mr Knightley’s love for Emma, and the idea that he may have other motives for moving to Hartfield - being that Knightley is one of my favourite Austen heroes!

I really liked the links made between fossils and Austen’s writing in ‘Persuasion’. I’d never thought of these as related topics, and it gave me a new view of Austen’s life and writings. Seeing how opinions have changed over time on ‘Persuasion’ and the novels was particularly interesting, given that ‘Persuasion’ is my favourite of Austen’s novels. The associations made between the changing hands of the throne and Austen’s characters provided a different angle to some of the concepts within the novel. I really loved her point about how Austen takes the pen in her own hands, allowing women to write their own stories.

Although I disagreed with some of the arguments made in the book, I generally enjoyed reading it and it provided new insights into her novels! As Helena Kelly recommends with her final line, maybe I should “read them again”.

The publishers seem to suggest that this is the first book of its kind, but if one delves into the literature on Austen, there is a multitude of articles and books that focus on her political opinions and the way the novels captivate this.

The introduction was structured interestingly, as it opens from Austen’s perspective, but in the third person. Tracing how Austen’s image has been built over time was a good way of establishing the argument within certain contexts.

‘Northanger Abbey’ was written about somewhat disparagingly at points, especially in the opening of the chapter - I have many friends who love this novel and Catherine!

Her exploration of references to pregnancy was interesting, and not a topic I had much considered in the context of Austen. However, I do feel there are other radical aspects that have been missed, such as her mocking of prescriptive literature about female behaviour.

In the chapter on ‘Sense and Sensibility’, the discussion of inheritance and the role of women in the home and the family was interesting. However, beyond this the author seems to be searching for something perverse, and, in my opinion, reads in symbolism that isn’t there - particularly with regards to the behaviours of Edward Ferrars. Beyond this, there are some leaps in logic when it comes to discussions about Colonel Brandon and questions about names within the novel. I wasn’t really convinced by the arguments within this chapter.

Her focus on the militia within ‘Pride and Prejudice’ was very interesting and she addressed things I had not considered before, such as the militia being a disruptive presence throughout the novel. The passages on Mr Collins were very entertaining as he is just absurd. I also particularly enjoyed the section on introductions and the politics of these within the era that Austen was writing. I also liked her discussion of the radical natures of Lizzy and Darcy, and how well matched they are, as it sung to the romantic in me. This chapter was more engaging and seemed to be better grounded in the primary material in its readings of Austen.

The ‘Mansfield Park’ chapter is very interesting, particularly with regards to slavery and the experiences that Austen would have known about and been linked to during her life. The associations made between character names and real life people provided insights that I was unaware of before reading this. Her argument regarding the connections between the church and slavery was well researched and grounded in the text. It had never occurred to me before how unsatisfactory the ending is for Fanny, as Edmund is not a true hero or a particularly great man. I think I need to revisit this novel and reassess!

The chapter on ‘Emma’ begins with rather a lot of preamble regarding enclosures. The information was rather interesting, but I am a history student who has previously studied this topic and has some background knowledge. I’m unsure how useful it all is for those who are just curious to hear about the political nature of ‘Emma’. Enclosures in ‘Emma’ is not a theme I had ever picked up on whilst reading it, as I had not looked this closely. Kelly’s arguments are good on this topic and reveal a different side to the novel to what I had previously seen.

I was slightly upset by her questioning of Mr Knightley’s love for Emma, and the idea that he may have other motives for moving to Hartfield - being that Knightley is one of my favourite Austen heroes!

I really liked the links made between fossils and Austen’s writing in ‘Persuasion’. I’d never thought of these as related topics, and it gave me a new view of Austen’s life and writings. Seeing how opinions have changed over time on ‘Persuasion’ and the novels was particularly interesting, given that ‘Persuasion’ is my favourite of Austen’s novels. The associations made between the changing hands of the throne and Austen’s characters provided a different angle to some of the concepts within the novel. I really loved her point about how Austen takes the pen in her own hands, allowing women to write their own stories.

Although I disagreed with some of the arguments made in the book, I generally enjoyed reading it and it provided new insights into her novels! As Helena Kelly recommends with her final line, maybe I should “read them again”.

This book was super fun! I always knew Jane Austen wasn't just a romance writer who was clueless about the events of her time. This book lines out all the ways Austen's books tackle those topics head on, we just didn't know the secret code that her contemporary readers would have known. She chose place names names and character names that would alert her readers to the theme of what she was really talking about, while making the plots seem innocuous and gentle. This was fascinating.

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

This is a strange book and (sorry) a ludicrous one. There's plenty of context, but the method and manner in which Kelly sets about "radicalising" Austen means ignoring all of the work on Austen that came before. Like, Emma is not "about" enclosures and Mr. Knightley is not simply a kind of Marie Antoinette. These are issues percolating through the book and these are factors that must be considered, of course: class, gender, politics. Doing so makes for fruitful reading. But this is a book of wilful misreading. Instead of seeing how class relations inform social relationships and character, Kelly wants to see Emma (or the other novels) as being specifically about Austen's radical politics as determined solely by Kelly and Kelly herself. It's a weird way to read a book.

It's a disservice to Austen as a writer to be so uninterested in how the novels work while imputing a whole hodgepodge of politically correct ideas to the author to update her for our modern times. There's really no need to panic if it turns out that Austen might have been a conservative and a snob and a product of her social environment and class. It makes the contrasting ideas and perspectives in her novels all the more intriguing because it was a mind at work and the ideological tensions are worth sorting out. Kelly's tone, meanwhile, is dismissive of all the Austen scholarship that came before. She delves deep into the books but puts forth rather bizarre conclusions that it's hard not to see this book as more about herself and less about Austen and her novels.

It's a disservice to Austen as a writer to be so uninterested in how the novels work while imputing a whole hodgepodge of politically correct ideas to the author to update her for our modern times. There's really no need to panic if it turns out that Austen might have been a conservative and a snob and a product of her social environment and class. It makes the contrasting ideas and perspectives in her novels all the more intriguing because it was a mind at work and the ideological tensions are worth sorting out. Kelly's tone, meanwhile, is dismissive of all the Austen scholarship that came before. She delves deep into the books but puts forth rather bizarre conclusions that it's hard not to see this book as more about herself and less about Austen and her novels.

challenging

informative

reflective

medium-paced

Helena Kelly knows her English history, and uses it to illuminate the context of Austen’s novels beyond the drawing rooms in which they take place. If her theories are sometimes far-fetched, they are always thought-provoking, and are looking to tie back to that history. No doubt I will be thinking of her ideas the next time I revisit the texts, even as I doubt I will be taking some of her theories to heart. more