Take a photo of a barcode or cover

adventurous

emotional

informative

inspiring

sad

medium-paced

adventurous

informative

inspiring

medium-paced

adventurous

challenging

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

Great prose - but for a book this concerned with photographs, having fewer than a dozen of the described images in the pages is a travesty and a major flaw. (Not to mention putting the few there were at the end of the chapters, rather than interleaved where they would reinforce the descriptions.) Having to repeatedly google images really jerks the reader out of the narrative text - in a way I think Curtis himself would have understood and disapproved.

adventurous

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

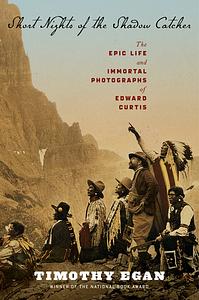

This is one of the best books I have read this year. I bought the book for a dollar at a library bookstore, and when I opened it was signed by the author. The story is about the photographer Edward Curtis who documented Native Americans in both portraits and film during the turn of the century. Curtis came from a poor family and was injured while he was a young man, but he had such physical energy that he became a master photographer and ethnologist. He struggled to maintain his pursuits, but was able to obtain funding from JP Morgan to publish a two volume set of photographs for libraries. The set of photographs were later sold by JP Morgan’s estate to a Boston bookstore for $1000 and languished in the basement until a clerk found them and realized their value. Curtis’s photos can also be seen in Ken Burn’s documentary The West, as well as a film called Coming to Light. The latter film shows interviews with current day Native Americans and the range of responses from joy at seeing their history recorded to anger that spiritual ceremonies that were private should not have been recorded. Curtis was very attached to the Hopi tribe and recorded what he believed was a Snake dance, but he was being mislead and dancers were later arrested by tribal police for letting Curtis record them. Despite any criticism, the artwork stands on its own merit as the portraits are stunning. Today the two volume set of photos sells for more than a million dollars.

adventurous

informative

reflective

medium-paced

Excellent history. I want to track down a 20 volume set of The North American Indian and spend all day perusing it.

informative

I have loved everything of Timothy Egan's that I've read, and Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher is no exception. I believe Egan is so skilled at narrative nonfiction that he could probably make me interested and invested in any topic.

Edward Curtis is a bit foreign to me. Anyone who has an overriding obsession that consumes decades of life and entire fortunes, excluding all else, and alienating friends and family members alike, is someone that I can't entirely understand. If life is about balance, Edward Curtis has weighted one end of his teeter totter so much that the force of it has catapulted everything else into the next county. But his drive for accuracy, and his documentation of customs and languages is invaluable.

The whole project seems bound in exploitation: Curtis for the Indians and J.P. Morgan for Curtis. Curtis paid, or offered to pay, each person who sat for a portrait. He staged many scenes, and asked people to wear costumes and act in ways that might be true to history, but was not the contemporary record that he was marketing. He pushed and pushed for secrets that some weren't willing to share, to the detriment of the people who eventually succumbed and divulged. Is there an element of voyeurism in studying so passionately a history that isn't your own?

And then there's Curtis' deal with J.P. Morgan and his company. Curtis had already sunk his fortune into his enterprise, and, as seems so often the case in life, the people who hold the purse strings control the game. Curtis agreed to work for free, which left him perpetually destitute as he then spent all of his time on the project. And he eventually gave more and more control of the project over to the Morgan Company, finally even the ownership of his life's work - the copyright and the photo negatives.

Finally, the book brings to light the tragedy of American policy towards the Native American population. Not only the constant backpedaling and outright lying about treaties and reservations, and exposure to disease and alcohol; what seems almost worse, to me, is the policy of forced assimilation: outlawing traditional practices and ceremonies, deliberately stripping away their pride, culture, religion, and heritage.

What makes Curtis a visionary though, is that, despite the artifice and exploitation, his work has proved an invaluable source of information about language and ceremony to modern tribes. Curtis knew that he was working for posterity, that the information he was gathering was dying out. And like many true artists, the extent of his brilliance and contribution is only recognized after his own death.

I was a bit disappointed that Egan didn't include more of the technical aspects of how photography worked at the beginning of the 20th century, and just how cumbersome and fragile glass plate negatives are to work with. Curtis hauled a whole bunch of stuff into some places that were quite off the beaten path. Egan talks a little about the finishing process, but I was eager for more.

Edward Curtis is a bit foreign to me. Anyone who has an overriding obsession that consumes decades of life and entire fortunes, excluding all else, and alienating friends and family members alike, is someone that I can't entirely understand. If life is about balance, Edward Curtis has weighted one end of his teeter totter so much that the force of it has catapulted everything else into the next county. But his drive for accuracy, and his documentation of customs and languages is invaluable.

The whole project seems bound in exploitation: Curtis for the Indians and J.P. Morgan for Curtis. Curtis paid, or offered to pay, each person who sat for a portrait. He staged many scenes, and asked people to wear costumes and act in ways that might be true to history, but was not the contemporary record that he was marketing. He pushed and pushed for secrets that some weren't willing to share, to the detriment of the people who eventually succumbed and divulged. Is there an element of voyeurism in studying so passionately a history that isn't your own?

And then there's Curtis' deal with J.P. Morgan and his company. Curtis had already sunk his fortune into his enterprise, and, as seems so often the case in life, the people who hold the purse strings control the game. Curtis agreed to work for free, which left him perpetually destitute as he then spent all of his time on the project. And he eventually gave more and more control of the project over to the Morgan Company, finally even the ownership of his life's work - the copyright and the photo negatives.

Finally, the book brings to light the tragedy of American policy towards the Native American population. Not only the constant backpedaling and outright lying about treaties and reservations, and exposure to disease and alcohol; what seems almost worse, to me, is the policy of forced assimilation: outlawing traditional practices and ceremonies, deliberately stripping away their pride, culture, religion, and heritage.

What makes Curtis a visionary though, is that, despite the artifice and exploitation, his work has proved an invaluable source of information about language and ceremony to modern tribes. Curtis knew that he was working for posterity, that the information he was gathering was dying out. And like many true artists, the extent of his brilliance and contribution is only recognized after his own death.

I was a bit disappointed that Egan didn't include more of the technical aspects of how photography worked at the beginning of the 20th century, and just how cumbersome and fragile glass plate negatives are to work with. Curtis hauled a whole bunch of stuff into some places that were quite off the beaten path. Egan talks a little about the finishing process, but I was eager for more.