Take a photo of a barcode or cover

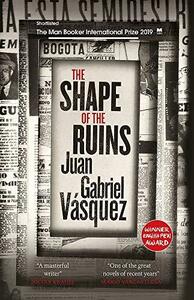

What a book! Mixing historical fiction, auto-fiction and literary fiction to explore Colombian history (which I knew next to nothing about), with conspiracy theories and detective work thrown in. Very readable too. Beautifully written.

4,5

Random thoughts written whilst I was reading this book for Dewey's readathon:

I’m reading a book that’s long listed for The International Man Booker Prize, The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vasquez. The style of the book reminds me of last years long listed novel (without fiction), The Impostor, in that it deals with real life events that the author is trying to figure out. This one looks at two political assassinations in Colombia – as well as a few outside Colombia – and at the men who become obsessed with conspiracies surrounding the murders. Was there really only one murderer? What was the objective? What actually happened, and why are we made to believe that something else happened? The book is fascinating on several levels. I’m learning quite a bit about Colombian history, as well as about how conspiracy theorists think, and about how people, both conspiracy theorists and others – can become obsessed with an event or a topic. I’m really enjoying this so far.

I thought I wanted variation, but I couldn’t get into When All is Said, so I went back to The Shape of the Ruins. The author is resisting still, but he seems to be getting more and more sucked into the conspiracy world. In his defense it is mostly out of curiosity than actual belief, and the story he is weaving is a compelling outsider narrative. I’m going to have to google Gaitán at some point, to get a real world view on his life and assassination. I am curious to know how much of this book is fiction, because it does read as non-fiction so far.

Still reading The Shape of the Ruins. It seems much more like a novel to me now than it did in the beginning. For the past two chapters we’ve been getting information on the assassination of General Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914, but we’re getting it from the point of view of the conspiracy theorists, which is interesting because it makes it seem as if they are the sane ones. It portrays the case as they see it. Problem with this from a readers perspective is that we (well, most of us probably) have no information about the assassination other than what we are provided in the book, so we have no way of knowing if the information is accurate, skewed or false. Conspiracies do happen, so we can’t reject it outright when we are presented with information which seems to lead in that direction. I’m very curious to find out more and to see if the case is as obvious as it seems at this moment (I’m guessing not). I might try and find out more on my own as well. I love these kinds of reads, where nothing is clearcut and the reader might be fooled again and again.

Anzola can give no real evidence for his hypothesis that the two men charged with the murder of Uribe didn’t act alone. He cannot show there was a cover up, nor that powerful men was behind the assassination. His standard of evidence is low and he has decided on the facts and is trying to procure the evidence for those facts. Carballo believes blindly in him, though, and I’m still not sure how this will be tied to the assassination of Gaitán in 1948. I think I might actually finish this book before the end of the readathon, though, which I didn’t think I’d manage.

The ending was great. The author tied the two assassinations together in a simple but believable way, and made Carballo seem a lot more human than he previously had seemed. It's amazing what we might be willing to believe to make sense of something senseless, to find meaning in horrible events and circumstances. I'm definitely hoping to find this on the Man Booker International Prize short list.

Random thoughts written whilst I was reading this book for Dewey's readathon:

I’m reading a book that’s long listed for The International Man Booker Prize, The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vasquez. The style of the book reminds me of last years long listed novel (without fiction), The Impostor, in that it deals with real life events that the author is trying to figure out. This one looks at two political assassinations in Colombia – as well as a few outside Colombia – and at the men who become obsessed with conspiracies surrounding the murders. Was there really only one murderer? What was the objective? What actually happened, and why are we made to believe that something else happened? The book is fascinating on several levels. I’m learning quite a bit about Colombian history, as well as about how conspiracy theorists think, and about how people, both conspiracy theorists and others – can become obsessed with an event or a topic. I’m really enjoying this so far.

I thought I wanted variation, but I couldn’t get into When All is Said, so I went back to The Shape of the Ruins. The author is resisting still, but he seems to be getting more and more sucked into the conspiracy world. In his defense it is mostly out of curiosity than actual belief, and the story he is weaving is a compelling outsider narrative. I’m going to have to google Gaitán at some point, to get a real world view on his life and assassination. I am curious to know how much of this book is fiction, because it does read as non-fiction so far.

Still reading The Shape of the Ruins. It seems much more like a novel to me now than it did in the beginning. For the past two chapters we’ve been getting information on the assassination of General Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914, but we’re getting it from the point of view of the conspiracy theorists, which is interesting because it makes it seem as if they are the sane ones. It portrays the case as they see it. Problem with this from a readers perspective is that we (well, most of us probably) have no information about the assassination other than what we are provided in the book, so we have no way of knowing if the information is accurate, skewed or false. Conspiracies do happen, so we can’t reject it outright when we are presented with information which seems to lead in that direction. I’m very curious to find out more and to see if the case is as obvious as it seems at this moment (I’m guessing not). I might try and find out more on my own as well. I love these kinds of reads, where nothing is clearcut and the reader might be fooled again and again.

Anzola can give no real evidence for his hypothesis that the two men charged with the murder of Uribe didn’t act alone. He cannot show there was a cover up, nor that powerful men was behind the assassination. His standard of evidence is low and he has decided on the facts and is trying to procure the evidence for those facts. Carballo believes blindly in him, though, and I’m still not sure how this will be tied to the assassination of Gaitán in 1948. I think I might actually finish this book before the end of the readathon, though, which I didn’t think I’d manage.

The ending was great. The author tied the two assassinations together in a simple but believable way, and made Carballo seem a lot more human than he previously had seemed. It's amazing what we might be willing to believe to make sense of something senseless, to find meaning in horrible events and circumstances. I'm definitely hoping to find this on the Man Booker International Prize short list.

emotional

informative

mysterious

reflective

medium-paced

Strong character development:

Yes

Intriguing novel, and intriguing introduction to Colombian political history / conspiracy theories. I found the first 100-150 pages and the ending as well really compelling, but it lost my patience in the middle with a long-winded, repetitive story-within-a-story.

Es un libro fascinante. Me encantó leer una novela histórica sobre Colombia. Yo no suelo leer novelas históricas de mi país así que leer una de ellas fue una experiencia muy gratificante. El único "pero" que le tengo al libro es que los capítulos son muy largos. Me gusta más leer capítulos cortos, pero en general la historia tiene una narración muy buena y la historia lo absorbe a uno, pese a lo largo que es el libro he pasado las páginas casi sin sentirlas. Me motiva a leer más sobre la historia de mi país.

An fictionalized exploration of Colombian assassination conspiracy theories

I’m sorry to spoil your theories, but someone had to tell you one day that Santa Claus was your parents.

The Shape of Ruins translated (wonderfully as ever) by Anne McLean from Juan Gabriel Vásquez's La forma de las ruinas is based around two pivotal assassinations in 20th Century Colombian political history, and the conspiracy theories that swirled around each.

There are two ways to view or contemplate what we call history: one is the accidental vision, for which history is the fateful product of an infinite chain of irrational acts, unpredictable contingencies and random events (life as unremitting chaos which we human beings try desperately to order); and the other is the conspiratorial vision, a scenario of shadows and invisible hands and eyes that spy and voices that whisper in corners, a theatre in which everything happens for a reason, accidents don’t exist and much less coincidences, and where the causes of events are silenced for reasons nobody knows. “In politics, nothing happens by accident,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt once said. “If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way.” This phrase, which I haven’t been able to find quoted in any reliable source, is loved by conspiracy theorists.

In 1914, as the Great War raged in Europe, itself triggered of course by an assassination by Gavrilo Princip, In October of the same year, but on the other side of the world, a man who was not an archduke, but a General and a senator of the Republic of Colombia, was assassinated, not by bullets but the hatchet blows of two poor young men like Princip. Rafael Uribe Uribe, veteran of several civil wars, uncontested leader of the Liberal Party (in those days when being a liberal meant something) was attacked at midday on the 15th by Leovigildo Galarza and Jesús Carvajal, unemployed carpenters.

And, three decades later, the assassination by a lone gun man, Juan Roa Sierra, on 9 April 1948 of the great Liberal caudillo Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, hero of the people and future president of the Republic of Colombia (although in a later account of Gaitán in the closing pages of the novel, he comes across as something of a dangerous populist in his tactics, if not his policies, freely borrowing from the cult created by Mussolini.)

This last killing eerily foreshadowed the assassination, 15 years later, of John F Kennedy, with the reputed killer himself killed shortly afterwards (albeit here at the hands of an angry mob), followed by a wave of conspiracy theories and reports of a second gunman:

Like all Colombians, I grew up hearing that Gaitán had been killed by the Conservatives, that he’d been killed by the Liberals, that he’d been killed by the Communists, that he’d been killed by foreign spies, that he’d been killed by the working classes feeling themselves betrayed, that he’d been killed by the oligarchs feeling themselves under threat; and I accepted very early, as we’ve all come to accept over time, that the murderer Juan Roa Sierra was only the armed branch of a successfully silenced conspiracy.

Although Kennedy's death can be seen as the start of a wave of political violence that characterised the 1960s in the US, the effect of Gaitán's death was more dramatic. On the day itself it triggered ten-hours of rioting, and retaliatory violence from the authorities, with up to 3,000 people believed to have been killed, an event referred to as the Bogotazo the grandiloquent nickname that we Colombians gave to that legendary day a long time ago.

And this was followed by a ten-year civil war, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths, and with repurcussions, such as the drug-gang violence from Pablo Escobar's Medellín Cartel in the 1980-1990s.

Colombians don’t agree on many things, but we do all think that Gaitán’s murder was the direct cause of the Bogotazo, with its three thousand casualties, as well as the opening shot of the Violencia that would end eight years and three hundred thousand deaths later.

...

April 9 is a void in Colombian history, yes, but it is other things besides: a solitary act that sent a whole nation into a bloody war; a collective neurosis that has taught us to distrust each other for more than half a century.

The book draws some interesting links between these events and the great Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez. In the interviews with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza documented in the book El Olor de la Guayaba (The Fragrance of the Guava), García Márquez reveals that the character of Colonel Aureliano Buendía in One Hundred Years of Solitude was loosely based on Rafael Uribe Uribe.

And in his autobiography, Vivir para contarla (Living to Tell The Tale) García Márquez hints at conspiracies behind the Gaitán murder, in particular a shadowy figure reputed to have incited the mob to take revenge on the alleged killer:

Many years later, in my days as a reporter, it occurred to me that the man had managed to have a false assassin killed in order to protect the identity of the real one.

The novel is narrated by a Colombian novelist called (you've guessed it) Juan Gabriel Vásquez. As the novel opens, his wife is about to give birth to two very premature babies (as happened in the real author's life) and he also encounters a surgeon who turns out to have parts of the post-autopsy remains of Gaitán in his personal possession, inherited from his father who performed the autopsy - things that really happened in the author's life (the real life doctor is called Leonardo Garavito). Juan Gabriel Vásquez explained his reason for this auto-fictional approach in an interview:

I swear that I thought, after finishing The Sound of Things Falling, that my personal accounts with the violence it had fallen to me to live through were settled. Now it seems incredible that I hadn’t understood that our violences are not only the ones we had to experience, but also the others, those that came before, because they are all linked even if the threads that connect them are not visible, because past time is contained within present time, or because the past is our inheritance without the benefit of an inventory and in the end we eventually receive it all: the sense and the excesses, the rights and the wrongs, the innocence and the crimes.

Although much of the novel is fictional, particularly the creation of an conspiracy theory obsessive, Carlos Carballo, a protege of the surgeon's father. Within minutes of meeting him, Carballo has explained to our narrator what really happened on 9/11 and with Princess Diana, before turning to his favourite topic - the April 9, 1948 killings and the suspicious similarities with Kennedy's death (and 9/11):

What did Juan Roa Sierra and Lee Harvey Oswald have in common? They were both accused of acting alone, of being lone wolves. Second: they both represented the enemy in their historic moment. Juan Roa Sierra was later accused of having Nazi sympathies, I don’t know if you remember: Roa worked at the German Embassy and brought Nazi pamphlets home, everybody found out about that. Oswald, of course, was a communist. ‘That’s why they were chosen,’ Carballo told me, ‘because they were people who wouldn’t awaken solidarity of any kind. They were the public enemy of the moment: they represented it, they incarnated it. If it were now, they would have been Al-Qaeda. That makes it much easier for people to swallow the story.’ Third: both assassins were, in turn, murdered almost immediately. ‘So they wouldn’t talk,’ Carballo told me, ‘isn’t it obvious?’

In another neat García Márquez link, Carballo claims to be a years younger than he actually is, so that his birth date can coincide with the events of 1948:

García Márquez had done something similar: for many years he maintained that he was born in 1928, when he was actually born a year earlier. The reason? He wanted his birth to coincide with the famous massacre at the banana plantation that became one of his obsessions, and which he described or reinvented in the best chapter of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

And as Carballo strings him a succession of increasingly fantastical stories about himself, the narrator also recalls Sebald:

I hadn’t made such a marvellous discovery since the day in 1999 when I opened the strange book of a certain W.G. Sebald.

...

A page of The Emigrants came to mind in which Sebald talks about Korsakoff syndrome, that disease of the memory that consists of inventing memories to replace true ones that have been lost, and I wondered if it weren’t possible that Carballo suffered from something similar.

At one point another character tells the narrator:

Conspiracy theories are like creepers, Vásquez, they grab onto whatever they can to climb up and keep growing until someone takes away what sustains them.

But of course that is not really true - conspiracy theories often have such tangled roots that even with the lack of any sustaining source and the removal of their underpinning (in the 1948 case, the autopsy proved that the bullets all came from one gun) the theories still flourish.

Much of the story to around half way relates the various encounters of the narrator and Carballo over the years, culminating into a visit to his house, where he reveals some of his treasures, in particular a now obscure, but once famous, book written on the Uribe Uribe killing by one Marco Tulio Anzola, who forms a role model for Carballo's own exhaustive investigations.

In a rather odd editorial decision, over two hundred pages (40%) of the book is then devoted to an exhaustive, and factual not fictional, examination into the Uribe Uribe murder.

In real-life, a young man, Marco Tulio Anzola was commissioned by the General's family to mount a private investigation into the death, and after several years produced a detailed account which, in contradiction to the official judicial view, claimed to reveal a widespread conspiracy as well as (inevitably) a third killer who escaped the scene.

It was published as a book Asesinato del general Rafael Uribe Uribe. Quienes son? (The Assassination of General Rafael Uribe Uribe. Who Are They?) in 1917 (https://www.worldcat.org/title/asesinato-del-general-rafael-uribe-uribe-quienes-son/oclc/24144459) and caused a sensation at the time, Anzola being permitted to call various witnesses to the trial of the alleged sole murderers, but his account, while compelling as a story, failed to reach judicial standards of proof. As a newspaper reported at the time:

It is a simple and very easy labour to suggest, in any sort of matter, vague and sinister complicities; the popular spirit is very fertile soil for those kinds of seeds; in it suspicion catches, even the most absurd, marvellously fast; however, that wasn’t what was expected of Señor Anzola, but proof and concrete accusations, and the country was left waiting.

his case collapsed and he was discredited, and eventually arrested for attacking a police officer and faded into obscurity.

In the novel, our narrator is pressured by Carballo into reading the book:

I opened Who Are They? and flipped through pages without disguising my boredom. There were three hundred pages of cramped type

and while he ultimately finds the account fascinating, it is also highly confusing, and easy to lose track of exactly why being able to prove such and such a person was in a particular place at a certain time is quite so key:

“Emilio Beltrán,” I said. “Rings a bell, but I don’t remember who he was.”

The problem for the reader of The Shape of the Ruins is that Juan Gabriel Vásquez essentially rewrites a second-had version of Who are They?, which if it is 'only' 200 pages not 300 still produces very similar sensations of boredom, at times, and confusion.

I felt some sympathy to Anzola, as a person, but entirely unconvinced of his findings - the former was surely the author's intention, but the latter possibly wasn't. The theories of Who Are They? are built on the usual sources of crackpots, publicity seekers and delusional and contradictory witnesses - where, in fact, the only sources of agreement are those entirely consistent with the official account. And yet Anzola believes that too is a conspiracy - the witnesses have been bribed to undermine their own credibility. At one point he even accuses the key figure in the whole conspiracy, another senior General, of causing the death of his own mother to avoid a court appearance.

Anzola uses the press to give public voice to his accusations: launching these difficult contentions from the tribune of the free press.

But as the author has said in the aforementioned interview, one of the perfidious effects of 21st century conspiracy theories as a tool used by political populists (see Brexit, the Labour left, Trump) is to undermine the free press not by suppression or censorship, but simply by destroying belief in any objective authoritative truth.

It is all fascinating in many sense, but this section rather uses a sledgehammer to the reader's patience to make its point.

The novel does however end strongly. The narrator gives us Carballo's back story, and we and the narrator come to have some sympathy with what drives his obsession. The narrator also presents a balanced rationale for the competing cock-up versus conspiracy theories of the chaos that seems to govern our lives. Carballo argues:

He understood that, Vásquez, he understood that terrible truth: that they were killed by the same people. Of course I’m not talking about the same individuals with the same hands, no. I’m talking about a monster, an immortal monster, the monster of many faces and many names who has so often killed and will kill again, because nothing has changed here in centuries of existence and never will change, because this sad country of ours is like a mouse running on a wheel.

Overall, an extremely impressive novel. This is my fourth Juan Gabriel Vásquez novel and I think the best. Middle section aside this could have been 5 star territory, but a good 4 stars, and a strong shortlist contender for the MBI.

The Shape of Ruins translated (wonderfully as ever) by Anne McLean from Juan Gabriel Vásquez's La forma de las ruinas is based around two pivotal assassinations in 20th Century Colombian political history, and the conspiracy theories that swirled around each.

There are two ways to view or contemplate what we call history: one is the accidental vision, for which history is the fateful product of an infinite chain of irrational acts, unpredictable contingencies and random events (life as unremitting chaos which we human beings try desperately to order); and the other is the conspiratorial vision, a scenario of shadows and invisible hands and eyes that spy and voices that whisper in corners, a theatre in which everything happens for a reason, accidents don’t exist and much less coincidences, and where the causes of events are silenced for reasons nobody knows. “In politics, nothing happens by accident,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt once said. “If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way.” This phrase, which I haven’t been able to find quoted in any reliable source, is loved by conspiracy theorists.

In 1914, as the Great War raged in Europe, itself triggered of course by an assassination by Gavrilo Princip, In October of the same year, but on the other side of the world, a man who was not an archduke, but a General and a senator of the Republic of Colombia, was assassinated, not by bullets but the hatchet blows of two poor young men like Princip. Rafael Uribe Uribe, veteran of several civil wars, uncontested leader of the Liberal Party (in those days when being a liberal meant something) was attacked at midday on the 15th by Leovigildo Galarza and Jesús Carvajal, unemployed carpenters.

And, three decades later, the assassination by a lone gun man, Juan Roa Sierra, on 9 April 1948 of the great Liberal caudillo Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, hero of the people and future president of the Republic of Colombia (although in a later account of Gaitán in the closing pages of the novel, he comes across as something of a dangerous populist in his tactics, if not his policies, freely borrowing from the cult created by Mussolini.)

This last killing eerily foreshadowed the assassination, 15 years later, of John F Kennedy, with the reputed killer himself killed shortly afterwards (albeit here at the hands of an angry mob), followed by a wave of conspiracy theories and reports of a second gunman:

Like all Colombians, I grew up hearing that Gaitán had been killed by the Conservatives, that he’d been killed by the Liberals, that he’d been killed by the Communists, that he’d been killed by foreign spies, that he’d been killed by the working classes feeling themselves betrayed, that he’d been killed by the oligarchs feeling themselves under threat; and I accepted very early, as we’ve all come to accept over time, that the murderer Juan Roa Sierra was only the armed branch of a successfully silenced conspiracy.

Although Kennedy's death can be seen as the start of a wave of political violence that characterised the 1960s in the US, the effect of Gaitán's death was more dramatic. On the day itself it triggered ten-hours of rioting, and retaliatory violence from the authorities, with up to 3,000 people believed to have been killed, an event referred to as the Bogotazo the grandiloquent nickname that we Colombians gave to that legendary day a long time ago.

And this was followed by a ten-year civil war, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths, and with repurcussions, such as the drug-gang violence from Pablo Escobar's Medellín Cartel in the 1980-1990s.

Colombians don’t agree on many things, but we do all think that Gaitán’s murder was the direct cause of the Bogotazo, with its three thousand casualties, as well as the opening shot of the Violencia that would end eight years and three hundred thousand deaths later.

...

April 9 is a void in Colombian history, yes, but it is other things besides: a solitary act that sent a whole nation into a bloody war; a collective neurosis that has taught us to distrust each other for more than half a century.

The book draws some interesting links between these events and the great Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez. In the interviews with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza documented in the book El Olor de la Guayaba (The Fragrance of the Guava), García Márquez reveals that the character of Colonel Aureliano Buendía in One Hundred Years of Solitude was loosely based on Rafael Uribe Uribe.

And in his autobiography, Vivir para contarla (Living to Tell The Tale) García Márquez hints at conspiracies behind the Gaitán murder, in particular a shadowy figure reputed to have incited the mob to take revenge on the alleged killer:

Many years later, in my days as a reporter, it occurred to me that the man had managed to have a false assassin killed in order to protect the identity of the real one.

The novel is narrated by a Colombian novelist called (you've guessed it) Juan Gabriel Vásquez. As the novel opens, his wife is about to give birth to two very premature babies (as happened in the real author's life) and he also encounters a surgeon who turns out to have parts of the post-autopsy remains of Gaitán in his personal possession, inherited from his father who performed the autopsy - things that really happened in the author's life (the real life doctor is called Leonardo Garavito). Juan Gabriel Vásquez explained his reason for this auto-fictional approach in an interview:

Well, the reason had to do with the circumstances in which the novel was born. I met this surgeon who invited me to his place and showed me the human remains - right? - a vertebra that belonged to Jorge Eliécer Gaitán and then a part of the skull that belonged to Rafael Uribe Uribe. This happened in September of 2005. That was the same moment in my life in which my twin daughters were being born in Colombia - in Bogota. Now, they were born very prematurely - at 6 1/2 months - which is a complicated situation that led to my wife and me spending a lot of time at the hospital while the girls recovered in their incubators.His fictional alter-ego makes a similar point:

I saw myself immersed in this very strange situation in which I went to this guy's place to take in my hands the human remains of two victims of political violence in Colombia, and then I went back to the hospital to take my own girls into my hands.

And the situation was so - so potent with me that these questions began taking shape very slowly in my head. What relationship is there between the two moments? Is my country's violent past, is that transmissible? Will that go down generation after generation to reach, in some way, the lives of these girls that have just been born? How can I protect them from this legacy of violence? I have always been aware that my life has been shaped by the crime of Gaitan for personal reasons, family reasons, sociopolitical reasons. It has shaped my whole country and the life of everybody I know. And so I thought, will that happen to my girls?

And so I realized that inventing a narrator, inventing a personality different from myself would, in a way, diminish them - or rather, undermine the importance these events had for my life. So - making a narrator up would remove me from these events, these anecdotes. And I didn't want that to happen. I wanted to take moral responsibility, as it were, for everything that I was telling in the novel.

(from https://www.npr.org/2018/11/07/665219574/novelist-revisits-the-assassination-and-conspiracies-that-fueled-colombias-civil)

I swear that I thought, after finishing The Sound of Things Falling, that my personal accounts with the violence it had fallen to me to live through were settled. Now it seems incredible that I hadn’t understood that our violences are not only the ones we had to experience, but also the others, those that came before, because they are all linked even if the threads that connect them are not visible, because past time is contained within present time, or because the past is our inheritance without the benefit of an inventory and in the end we eventually receive it all: the sense and the excesses, the rights and the wrongs, the innocence and the crimes.

Although much of the novel is fictional, particularly the creation of an conspiracy theory obsessive, Carlos Carballo, a protege of the surgeon's father. Within minutes of meeting him, Carballo has explained to our narrator what really happened on 9/11 and with Princess Diana, before turning to his favourite topic - the April 9, 1948 killings and the suspicious similarities with Kennedy's death (and 9/11):

What did Juan Roa Sierra and Lee Harvey Oswald have in common? They were both accused of acting alone, of being lone wolves. Second: they both represented the enemy in their historic moment. Juan Roa Sierra was later accused of having Nazi sympathies, I don’t know if you remember: Roa worked at the German Embassy and brought Nazi pamphlets home, everybody found out about that. Oswald, of course, was a communist. ‘That’s why they were chosen,’ Carballo told me, ‘because they were people who wouldn’t awaken solidarity of any kind. They were the public enemy of the moment: they represented it, they incarnated it. If it were now, they would have been Al-Qaeda. That makes it much easier for people to swallow the story.’ Third: both assassins were, in turn, murdered almost immediately. ‘So they wouldn’t talk,’ Carballo told me, ‘isn’t it obvious?’

In another neat García Márquez link, Carballo claims to be a years younger than he actually is, so that his birth date can coincide with the events of 1948:

García Márquez had done something similar: for many years he maintained that he was born in 1928, when he was actually born a year earlier. The reason? He wanted his birth to coincide with the famous massacre at the banana plantation that became one of his obsessions, and which he described or reinvented in the best chapter of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

And as Carballo strings him a succession of increasingly fantastical stories about himself, the narrator also recalls Sebald:

I hadn’t made such a marvellous discovery since the day in 1999 when I opened the strange book of a certain W.G. Sebald.

...

A page of The Emigrants came to mind in which Sebald talks about Korsakoff syndrome, that disease of the memory that consists of inventing memories to replace true ones that have been lost, and I wondered if it weren’t possible that Carballo suffered from something similar.

At one point another character tells the narrator:

Conspiracy theories are like creepers, Vásquez, they grab onto whatever they can to climb up and keep growing until someone takes away what sustains them.

But of course that is not really true - conspiracy theories often have such tangled roots that even with the lack of any sustaining source and the removal of their underpinning (in the 1948 case, the autopsy proved that the bullets all came from one gun) the theories still flourish.

Much of the story to around half way relates the various encounters of the narrator and Carballo over the years, culminating into a visit to his house, where he reveals some of his treasures, in particular a now obscure, but once famous, book written on the Uribe Uribe killing by one Marco Tulio Anzola, who forms a role model for Carballo's own exhaustive investigations.

In a rather odd editorial decision, over two hundred pages (40%) of the book is then devoted to an exhaustive, and factual not fictional, examination into the Uribe Uribe murder.

In real-life, a young man, Marco Tulio Anzola was commissioned by the General's family to mount a private investigation into the death, and after several years produced a detailed account which, in contradiction to the official judicial view, claimed to reveal a widespread conspiracy as well as (inevitably) a third killer who escaped the scene.

It was published as a book Asesinato del general Rafael Uribe Uribe. Quienes son? (The Assassination of General Rafael Uribe Uribe. Who Are They?) in 1917 (https://www.worldcat.org/title/asesinato-del-general-rafael-uribe-uribe-quienes-son/oclc/24144459) and caused a sensation at the time, Anzola being permitted to call various witnesses to the trial of the alleged sole murderers, but his account, while compelling as a story, failed to reach judicial standards of proof. As a newspaper reported at the time:

It is a simple and very easy labour to suggest, in any sort of matter, vague and sinister complicities; the popular spirit is very fertile soil for those kinds of seeds; in it suspicion catches, even the most absurd, marvellously fast; however, that wasn’t what was expected of Señor Anzola, but proof and concrete accusations, and the country was left waiting.

his case collapsed and he was discredited, and eventually arrested for attacking a police officer and faded into obscurity.

In the novel, our narrator is pressured by Carballo into reading the book:

I opened Who Are They? and flipped through pages without disguising my boredom. There were three hundred pages of cramped type

and while he ultimately finds the account fascinating, it is also highly confusing, and easy to lose track of exactly why being able to prove such and such a person was in a particular place at a certain time is quite so key:

“Emilio Beltrán,” I said. “Rings a bell, but I don’t remember who he was.”

The problem for the reader of The Shape of the Ruins is that Juan Gabriel Vásquez essentially rewrites a second-had version of Who are They?, which if it is 'only' 200 pages not 300 still produces very similar sensations of boredom, at times, and confusion.

I felt some sympathy to Anzola, as a person, but entirely unconvinced of his findings - the former was surely the author's intention, but the latter possibly wasn't. The theories of Who Are They? are built on the usual sources of crackpots, publicity seekers and delusional and contradictory witnesses - where, in fact, the only sources of agreement are those entirely consistent with the official account. And yet Anzola believes that too is a conspiracy - the witnesses have been bribed to undermine their own credibility. At one point he even accuses the key figure in the whole conspiracy, another senior General, of causing the death of his own mother to avoid a court appearance.

Anzola uses the press to give public voice to his accusations: launching these difficult contentions from the tribune of the free press.

But as the author has said in the aforementioned interview, one of the perfidious effects of 21st century conspiracy theories as a tool used by political populists (see Brexit, the Labour left, Trump) is to undermine the free press not by suppression or censorship, but simply by destroying belief in any objective authoritative truth.

It is all fascinating in many sense, but this section rather uses a sledgehammer to the reader's patience to make its point.

The novel does however end strongly. The narrator gives us Carballo's back story, and we and the narrator come to have some sympathy with what drives his obsession. The narrator also presents a balanced rationale for the competing cock-up versus conspiracy theories of the chaos that seems to govern our lives. Carballo argues:

He understood that, Vásquez, he understood that terrible truth: that they were killed by the same people. Of course I’m not talking about the same individuals with the same hands, no. I’m talking about a monster, an immortal monster, the monster of many faces and many names who has so often killed and will kill again, because nothing has changed here in centuries of existence and never will change, because this sad country of ours is like a mouse running on a wheel.

Overall, an extremely impressive novel. This is my fourth Juan Gabriel Vásquez novel and I think the best. Middle section aside this could have been 5 star territory, but a good 4 stars, and a strong shortlist contender for the MBI.

I picked up this book because of a review in the Guardian, and because it was shorlisted for the Man Book international in 2019. This is almost three books in one, three stories, delineating the convulsions of Colombian history through two key political assassinations, the 1914 murder of General Rafael Uribe Uribe and the 1948 assassination of Jorge Eliecer Gaitan (which started the 10-year period known as La Violencia), both Liberal leaders. The 3rd storyline is the first person one. The three storylines are interwoven in a way that makes the book part history, part murder mystery, part reflection of what is history / History.

This is not an easy read. This is a book that demands your attention but is really well worth it.

This is not an easy read. This is a book that demands your attention but is really well worth it.

challenging

informative

mysterious

slow-paced

Strong character development:

Complicated

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

No

[English below]

Para ser sincera, me costó un poco (casi que quiero decir bastante) entrar en la historia y habituarme al lenguaje algo pomposo de Vásquez. Los capítulos son larguísimos y el narrador no da pinta de ser el más simpático del barrio, a decir verdad. Pero de una forma u otra, la curiosidad ganó y, sin darme cuenta, llegué al punto en que la novela tomó forma, el punto en el que la historia que Vásquez estaba contando empezó a adquirir un aire de misterio que era difícil de ignorar.

La forma de las ruinas es una mezcla de novela histórica, novela misterio, thriller y autobiografía (quién sabe hasta qué punto). El autor y el narrador comparten mucho más que el nombre, y es difícil separar el uno del otro, lo que le da a la historia una credibilidad extraña. Si el Vásquez que escribió el libro es prácticamente el mismo Vásquez que nos cuenta la historia, y si gran parte de la historia se basa en hechos reales, ¿qué tanto es cierto? ¿Qué tanto es ficción y qué tanto es historia? ¿Qué tanto peso tienen esas teorías conspirativas, al final del día?

Para ser sincera, me costó un poco (casi que quiero decir bastante) entrar en la historia y habituarme al lenguaje algo pomposo de Vásquez. Los capítulos son larguísimos y el narrador no da pinta de ser el más simpático del barrio, a decir verdad. Pero de una forma u otra, la curiosidad ganó y, sin darme cuenta, llegué al punto en que la novela tomó forma, el punto en el que la historia que Vásquez estaba contando empezó a adquirir un aire de misterio que era difícil de ignorar.

La forma de las ruinas es una mezcla de novela histórica, novela misterio, thriller y autobiografía (quién sabe hasta qué punto). El autor y el narrador comparten mucho más que el nombre, y es difícil separar el uno del otro, lo que le da a la historia una credibilidad extraña. Si el Vásquez que escribió el libro es prácticamente el mismo Vásquez que nos cuenta la historia, y si gran parte de la historia se basa en hechos reales, ¿qué tanto es cierto? ¿Qué tanto es ficción y qué tanto es historia? ¿Qué tanto peso tienen esas teorías conspirativas, al final del día?

«Eso que usted llama historia no es más que el cuento ganador, Vásquez. Alguien hizo que ganara ese cuento y no otros, y por eso le creemos hoy.»

La historia se centra en dos de los asesinatos más importantes y determinantes de la historia colombiana: el del General Rafael Uribe Uribe en 1914 y el de Jorge Eliecer Gaitán en 1914. Cuando Vásquez conoce a Carlos Carballo, un tipo obsesionado con teorías conspirativas, su vida empieza a girar en torno a éstas, por más que él intente evitarlo. La obsesión de Carballo es enfermiza. Él ve como su tarea el encontrar las pruebas de lo que él sabe que es verdad: que lo que la historia colombiana ha documentado sobre los asesinatos de Uribe Uribe y Gaitán no es completamente cierto, que a esa historia le falta mucha tela y que alguien se aseguró de que así fuera. Que si bien conocemos a los autores materiales, los autores intelectuales se salieron con la suya y siguieron (y siguen, porque siempre son los mismos) libres.

«Entendió que toda esa gente convencida de que a Gaitán lo iban a matar no era distinta de los que oyeron, con cuarenta días de anticipación, que iban a matar a Uribe. Entendió eso, Vásquez, entendió eso tan terrible: que los mató la misma gente. Por supuesto que no hablo de los mismos individuos con las mismas manos, no. Hablo de un monstruo, un monstruo inmortal, el monstruo de muchas caras y muchos nombres que tantas veces ha matado y matará otra vez, porque aquí nada ha cambiado en siglos de existencia y no va a cambiar jamás, porque este triste país nuestro es como un ratón corriendo en un carrusel.»

Vásquez dedica gran parte de la novela a un examen exhaustivo del asesinato de Uribe Uribe. No sé qué tan interesante sea esto para lectores internacionales pero para mí, que soy colombiana y que no tenía la más remota idea de este capítulo tan trascendental de la historia de mi país (cosa que no me sorprende: la educación en Colombia no es reconocida por darle mucho énfasis a la historia nacional), fue extremadamente cautivador.

Después de esa larga (que a veces tenía pinta de ser interminable) clase de historia, volvemos al presente y Vásquez por fin puede entender el vínculo entre los dos asesinatos e incluso el origen de la obsesión de Carballo. A pesar de que en más de una ocasión sentí perder el interés en la historia y en los personajes (ni Vásquez ni Carballo son especialmente simpáticos), las últimas páginas ataron los cabos sueltos de tal manera que todo cobró sentido con mucha fuerza. Vásquez incluso se ganó un par de puntos conmigo al reflexionar sobre la escritura y la labor de un escritor, sobre lo poco que conocemos nuestra propia historia y sobre el peso que nuestra historia nacional tiene sobre nosotros, nuestras vidas y nuestro entorno, y sobre las generaciones venideras.

Si el asesinato de Uribe Uribe se repitió años después con Gaitán, ¿quién dice que no vaya a repetirse nuevamente? En un país sin memoria y con tendencias a creer lo que más conviene, no es una pregunta descabellada. Es casi una profecía – una promesa.

«Y luego pensaba: es cierta precisamente porque no ha sobrevivido, porque la historia colombiana ha probado una y mil veces su extraordinaria capacidad para esconder versiones incómodas o para cambiar el lenguaje con el cual se cuentan las cosas, de manera que lo terrible o inhumano acaba convirtiéndose en lo más normal, o deseable, o incluso loable.»

++++++

[English]

To be honest, it took me a little while (I almost want to say a long time) to get into the story and get used to Vásquez's somewhat pompous language. The chapters are very long and the narrator isn’t always all too agreeable, to tell the truth. But one way or another, curiosity won out and, without realizing it, I reached the point where the novel took shape – the point where the story Vásquez was telling began to acquire an air of mystery that was hard to ignore.

The Shape of the Ruins is a mixture of historical novel, mystery novel, thriller and autobiography (who knows to what extent). The author and the narrator share much more than just the name, and it is difficult to separate one from the other, which gives the story a strange sense of credibility. If the Vásquez who wrote the book is practically the same Vásquez who tells us the story, and if much of the story is based on real events, how much is true? How much is fiction and how much is history? How much weight do these conspiracy theories have, at the end of the day?

“What you call history is no more than the winning story, Vásquez. Someone made that story win, and not any of the others, and that's why we believe it today.

The story focuses on two of the most important and decisive assassinations in Colombian history: that of General Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914 and that of Jorge Eliecer Gaitán in 1914. When Vásquez meets Carlos Carballo, a man obsessed with conspiracy theories, his life begins to revolve around them, no matter how hard he tries to avoid it. Carballo's obsession is sickening. He sees it as his mission in life to find the evidence for what he knows to be true: that what Colombian history has documented about the murders of Uribe and Gaitán is not completely true, that the story has a lot of holes and someone made sure of that. That although we know who the material authors were, the intellectual authors got away with it and remained (and remain, because they are always the same) free.

“He understood that terrible truth: that they were killed by the same people. Of course I’m not talking about the same individuals with the same hands, no. I’m talking about a monster, an immortal monster, the monster of many faces and many names who has so often killed and will kill again, because nothing has changed here in centuries of existence and never will change, because this sad country of ours is like a mouse running on a wheel.”

Vasquez devotes much of the novel to a thorough examination of the murder of Uribe Uribe. I don't know how interesting this is for international readers, but for me, a Colombian who didn't have the faintest idea of this pivotal chapter in my country's history (which doesn't surprise me: education in Colombia is not particularly known for giving much emphasis to national history), it was extremely captivating.

After that long (sometimes seemingly endless) history lesson, we return to the present where Vásquez finally understands the link between the two murders and even the origin of Carballo's obsession. Although on more than one occasion I felt I was losing interest in the story and the characters (neither Vásquez nor Carballo are particularly likeable), the last few pages tied up the loose ends in such a way that everything made sense, and then some. Vásquez even earned a couple of points with me by reflecting on writing and the work of a writer, on how little we know about our own history and on the weight that our national history has on us, our lives and our environment, and on the generations to come.

If Uribe's assassination was played over years later with Gaitán, who is to say that it will not be repeated again? In a country with no memory and a tendency to believe what suits best to those in power, this is not quite an unreasonable question. It is almost a prophecy - a promise.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez is quickly becoming a new favourite of mine. Having read The Sound of Things Falling and now The Shape of the Ruins, I cannot help but appreciate his style. I compared him to Roberto Bolaño in my previous review, mainly because they both like to insert themselves into the narrative. Bolaño has his alter ego Arturo Belano show up in a few of his novels. Whereas Juan Gabriel Vásquez just used the same name for his characters. I am positive this are not just a character that shares the same name. His approach to literature is to explore Columbian history in a fictionalised account, but I think that these characters are just a device to tell the reader how the past has affected him.

The Sound of Things Falling looks on the impact the Pablo Escoba had on Colombia. While The Shape of the Ruins is focused on the murders of both Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914 and Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948. Rafael Uribe Uribe’s political ideas lead to the establishment of Guild socialism and trade unions in Colombia, while Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was leader of a populist movement in Colombia. Their political ideology were very different but Vásquez uses the investigations into their deaths as a way to look at Colombia. Particularly how it lead to a ten year civil war known as La Violencia.

Within the novel these two political figures are often referenced in relation to two different facts. Rafael Uribe Uribe was the inspiration for the character General Buendia in Gabriel García Márquez’s in One Hundred Years of Solitude and Jorge Eliécer Gaitán is referred two as the Colombian J.F.K. Which to my mind made me automatically look at this novel as a way to explore the cultural significance of these two murders as well as Colombia on the world stage. Particularly the cycle of violence that is constantly putting the country in the news.

I find it difficult to review a novel like The Shape of the Ruins, not because there is not much to say, quite the opposite. In fact, it is because I do not know the history of Colombia well enough to voice any interesting opinions. Books like this are often referred to as autofiction, which is a literary term that refers to a fictionalised autobiography. Most works of fiction have elements of truth within the characters but these books are using the experience and history to build a story around it. I read translations because I want to understand the world a little better, and I appreciate the chance to learn their history in the process. This is why I love authors like Juan Gabriel Vásquez.

To be fair, I have been obsessed with Latin American history for a few months and I have so much to read and learn. I turn to Juan Gabriel Vásquez as a new default recommendation. He will sit next to Roberto Bolaño as some of my favourite authors from South America. There are plenty more authors to explore on this continent but I have to recommend Ariana Harwicz, Mariana Enríquez, Pola Oloixarac and Samanta Schweblin as well. These four have all been recently translated and make up some of the exciting emerging female authors coming out of the continent, although these four are all from Argentina.

Having read Juan Gabriel Vásquez in the past, I would recommend starting with The Sound of Things Falling. There is something about exploring the effects the drug cartels had on the country that appealed to me. The Shape of the Ruins is also a great novel and if you care more about the political landscape then jump straight to this novel. I have a few more novels to read from Juan Gabriel Vásquez, which I probably will not read this year, but they will be coming up soon. Please recommend me a Vásquez to try next, or just recommend me an author that has a similar style.

This review originally appeared on my blog; http://www.knowledgelost.org/book-reviews/genre/historical-fiction/the-shape-of-the-ruins-by-juan-gabriel-vasquez/

The Sound of Things Falling looks on the impact the Pablo Escoba had on Colombia. While The Shape of the Ruins is focused on the murders of both Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914 and Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948. Rafael Uribe Uribe’s political ideas lead to the establishment of Guild socialism and trade unions in Colombia, while Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was leader of a populist movement in Colombia. Their political ideology were very different but Vásquez uses the investigations into their deaths as a way to look at Colombia. Particularly how it lead to a ten year civil war known as La Violencia.

Within the novel these two political figures are often referenced in relation to two different facts. Rafael Uribe Uribe was the inspiration for the character General Buendia in Gabriel García Márquez’s in One Hundred Years of Solitude and Jorge Eliécer Gaitán is referred two as the Colombian J.F.K. Which to my mind made me automatically look at this novel as a way to explore the cultural significance of these two murders as well as Colombia on the world stage. Particularly the cycle of violence that is constantly putting the country in the news.

I find it difficult to review a novel like The Shape of the Ruins, not because there is not much to say, quite the opposite. In fact, it is because I do not know the history of Colombia well enough to voice any interesting opinions. Books like this are often referred to as autofiction, which is a literary term that refers to a fictionalised autobiography. Most works of fiction have elements of truth within the characters but these books are using the experience and history to build a story around it. I read translations because I want to understand the world a little better, and I appreciate the chance to learn their history in the process. This is why I love authors like Juan Gabriel Vásquez.

To be fair, I have been obsessed with Latin American history for a few months and I have so much to read and learn. I turn to Juan Gabriel Vásquez as a new default recommendation. He will sit next to Roberto Bolaño as some of my favourite authors from South America. There are plenty more authors to explore on this continent but I have to recommend Ariana Harwicz, Mariana Enríquez, Pola Oloixarac and Samanta Schweblin as well. These four have all been recently translated and make up some of the exciting emerging female authors coming out of the continent, although these four are all from Argentina.

Having read Juan Gabriel Vásquez in the past, I would recommend starting with The Sound of Things Falling. There is something about exploring the effects the drug cartels had on the country that appealed to me. The Shape of the Ruins is also a great novel and if you care more about the political landscape then jump straight to this novel. I have a few more novels to read from Juan Gabriel Vásquez, which I probably will not read this year, but they will be coming up soon. Please recommend me a Vásquez to try next, or just recommend me an author that has a similar style.

This review originally appeared on my blog; http://www.knowledgelost.org/book-reviews/genre/historical-fiction/the-shape-of-the-ruins-by-juan-gabriel-vasquez/