You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

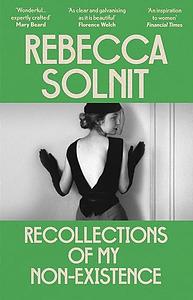

Beautifully thoughtful sentences. Structured in a way where each chapter had purpose and also covered some time in her life. Genuinely thought provoking about the experience of being a woman and being young. Made me love Solnit as a person and excited to read more of her work - that covers such diverse grounds. Some exceptional quotes

I always expect to be taken aback by Rebecca Solnit's writing. She has transformed the genre of creative non-fiction -- my favorite of her works being Men Explain Things to Me. Recollections of My Nonexistence was amazing in the same ways.

I love memoir, probably one of my favorite genres. This one was different in that Rebecca Solnit's eloquence and understanding of language add so many more layers to what is traditionally coined as "memoir."

I highly suggest listening to the audiobook as it is narrated by Solnit herself, and her voice makes it seem as if you're in conversation with her.

I love memoir, probably one of my favorite genres. This one was different in that Rebecca Solnit's eloquence and understanding of language add so many more layers to what is traditionally coined as "memoir."

I highly suggest listening to the audiobook as it is narrated by Solnit herself, and her voice makes it seem as if you're in conversation with her.

This probably shouldn’t have been where I started with reading Solnit. There were some brilliant nuggets of feminist wisdom throughout the book that I appreciated. However, I could not get engaged with the book as a whole. I also really didn’t like the audiobook performance, which was read by the author.

This book isn't just an ordinary memoir. It's thought-provoking and makes you think about much more than how you act as a woman in society. It made me ponder about the poetics of writing, about the way you observe people and society, about the things I value in life, about friendship, about why I like certain books so much...

Solnit's clear yet lyrical style is very inspirational and takes you on a very interesting journey that will make you think and smile.

Solnit's clear yet lyrical style is very inspirational and takes you on a very interesting journey that will make you think and smile.

challenging

dark

emotional

hopeful

informative

reflective

tense

slow-paced

It took a considerably long time to finish this once I started not because it was boring or slow but because I found myself staring out windows, contemplating memories I had forgotten or minimized. I’ve tried to read this book four times before and gotten to different parts and just wasn’t ready. A super interesting (horrifying) time to be reading this when Trump was elected.

I think Solnit did an incredible job of recollecting that nonexistence of being a woman, making it personal, without centering herself and with acknowledging the layers of oppression that are still under her without disregarding the layers she is under and trying to move with those other women. She describes feeling like if she’s not raped or murdered that these stifling feelings are out of proportion but then she describes a casual atmosphere of male violence and power that is ever present that makes so much sense in my body. It’s like we never had a chance to not feel like this.

It made me think a lot about that feeling I get when I am being harmed by a man’s misogyny or harassment so I feel awful and then suddenly I feel empathy and pity for him, especially when I stand up for myself, so then the man feels nothing and I feel the burden of both of these awfuls. And then on top of those awfuls, sometimes the judgement of other women on how you “handled” it, when really it’s just my flight/fight/freeze/fawn.

I’ve had the feeling before that I’d almost rather be a woman than a man under patriarchy because I have this community and history in collective support and the other side of patriarchy for men is being told their whole life the kind of man they should be and that not working and leaving them with profound loneliness and perpetuation of harm.

This week was a normal week for me. I got yelled at by a man that “God hates you and is going to murder you!” He followed me across the busy street. I didn’t want to be followed home so asked some men to escort me home. They told me that I shouldn’t worry and I shouldn’t look at men when they yell. They told me I should just punch them back. They told me I should get pepper spray. At work a man said I looked like a doll. At work another man said I looked good from the front and the back. A cashier asked my why my credit card was bent and when I told him he reached across the counter to squeeze my shoulder. This week was a normal week.

The last quarter of the book dropped off for me away from the theme a bit.

“(Later on I'd come to understand gentrification and the role that I likely played as a pale face making the neighborhood more palatable to other pale faces with more re-sources, but I had no sense at the start that things would change and how that worked.)”

“Though each incident I experienced was treated as somehow isolated and deviant, there were countless incidents, and they were of the status quo, not against or outside it. Talking about it made people uncomfortable, and mostly they responded by telling me what I was doing wrong. Some men told me they wished someone would sexually harass them, because they seemed to be unable to imagine it as anything but pleasant invitations from attractive people. No one was offering the help of recognizing what I was experiencing, or agreeing that I had the right to be safe and free.

It was a kind of collective gaslighting. To live in a war that no one around me would acknowledge as a war—I am tempted to say that it made me crazy, but women are so often accused of being crazy, as a way of undermining their capacity to bear witness and the reality of what they testify to. Besides, in these cases, crazy is often a euphemism for unbearable suffering. So it didn't make me crazy; it made me unbearably anxious, preoccupied, indignant, and exhausted.”

“I became expert at fading and slipping and sneaking away, backing off, squirming out of tight situations, dodging unwanted hugs and kisses and hands, at taking up less and less space on the bus as yet another man spread into my seat, at gradually disengaging, or suddenly absenting myself. At the art of nonexistence, since exis tence was so perilous. It was a strategy hard to unlearn on those occasions when I wanted to approach someone directly. How do you walk right up to someone with an open heart and open arms amid decades of survival-by-evasion? All this menace made it difficult to stop and trust long enough to connect, but it made it difficult to keep moving too, and it seemed sometimes as though it was all meant to wall me up alone at home like a person prematurely in her coffin.”

“You can drip one drop of blood into a glass of clear water and it will still appear to be clear water, or two drops or six, but at some point it will not be clear, not be water. How much of this enters your consciousness before your consciousness is changed? What does it do to all the women who have a drop or a teaspoon or a river of blood in their thoughts? What if it's one drop every day? What if you're just waiting for clear water to turn red? What does it do to see people like you tortured? What vitality and tranquility or capacity to think about other things, let alone do them, is lost, and what would it feel like to have them back?”

“Not everyone makes it through, and what tries to kill you takes a lot of your energy that might be better used elsewhere and makes you tired and anxious.”

“Contemplating the wonder that was Ed, dressed, I came to recognize that though looking amazing is usually thought of as either a mildly despicable self-glorification or a straightforward strategy to access sex, it can be a gift to the people around you, a sort of public art and a celebration, and, with wardrobes like Ed's, even a kind of wit and commentary.”

“We would like the people involved in monstrosity to be recognizably monstrous, but many of them are dili-gent, unquestioning, obedient adherents to the norms of their time, trained in what to feel and think and notice and what not to. The men who wrote these reports seemed like earnest bureaucrats, sometimes sympathetic to the plight of the people they were helping to exterminate, always convinced of their own decency. It is the innocence that constitutes the crime.”

Where do you stand? Where do you belong? Those are often questions about political stances or values, but sometimes the question is personal: Do you feel like you have ground to stand on? Is your existence justified in your own eyes, enough that you don't have to retreat or attack?

Do you have a right to be there, to participate, to take up space in the world, the room, the conversation, the historical record, the decision-making bodies, to have needs, wants, rights? Do you feel obliged to justify or apologize or excuse yourself to others? Do you fear the ground being pulled out from under you, the door slammed in your face? Do you not stake a claim to begin with, because you ve already been defeated or expect to be if you show up? Can you state what you want or need without its being regarded, by yourself or those you address, as aggression or imposition?

What does it mean neither to advance, like a soldier waging a war, nor to retreat? What would it be like to feel that you have that right to be there, when there is nothing more or less than the space you inhabit? What does it mean to own some space and feel that it's yours all the way down to your deepest reflexes and emotions?

What does it mean to not live in wartime, to not have to be ready for war?”

“Despite that Lewis book, I soaked up novels impossibly dramatic notions of love and romance and their myths of completion and ending. And I got something most women got, an experience of staring at women across a distance or being in worlds in which they barely existed, from Moby-Dick to Lord of the Rings. Being so often required to be someone else can stretch thin the sense of self. You should be yourself some of the time. You should be with people who are like you, who are facing what you're facing, who dream your dreams and fight your battles, who recognize you. And then, other times, you should be like people unlike yourself. Because there is a problem as well with those who spend too little time being anyone else; it stunts the imagination in which empathy takes root, that empathy that is a capacity to shape-shift and roam out of your sole self. One of the convenient afflictions of power is a lack of this imaginative extension.

For many men it begins in early childhood, with almost exclusively being given stories with male protagonists.”

“There was another kind of humor, or rather a ponderous vit, that was convoluted, full of citations and puns and plays on existing phrases, of circling around, far around, what was happening and what you were feeling. It was as though the more indirect and ref. erential your statement, the further away from your immediate and authentic reaction, the better. It would take me a long time to understand what a limitation cleverness can be, and to understand how much unkindness damaged not just the other person but the possibilities for you yourself, the speaker, and what courage it took to speak from the heart. What I had then was a voice that leaned hard on irony, on saying the opposite of what I meant, a voice in which I often said things to one person to impress other people, a voice in which I didn't really know much about what I thought and felt because the logic of the game determined the moves. It was a hard voice on a short leash.

That voice isn't just in your conversations, it's inside your head: you don't say that hurt, or I feel sad; you run angry tirades about why the other party is a terrible person over and over, and you layer on anger to avoid whatever's hurt or frightened underneath, unti. its certain that you don't know yourself or your weather, or that its you who's telling the story that's feeding the fire. You generally don't know other people either, except as they impinge on you; it’s a failure of imagination going in and reaching out.”

“You can read that as an insistence that we never get over anything, though it might make more sense as a reminder that though damage is not necessarily permanent, neither is repair. What is won or changed or fixed has to be maintained and protected or it can be lost. What goes forward can go backward. Efficiency says that grief should follow a road map and things should be gotten over and that then there should be that word that applies to wounds and minds both: closure. But time and pain are a more fluid, unpredictable business, expanding and contracting, closing and opening and changing.”

“You can read that as an insistence that we never get over anything, though it might make more sense as a reminder that though damage is not necessarily permanent, neither is repair. What is won or changed or fixed has to be maintained and protected or it can be lost. What goes forward can go backward. Efficiency says that grief should follow a road map and things should be gotten over and that then there should be that word that applies to wounds and minds both: closure. But time and pain are a more fluid, unpredictable business, expanding and contracting, closing and opening and changing.”

emotional

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

medium-paced

challenging

dark

emotional

hopeful

informative

inspiring

reflective

sad

tense

medium-paced

A most moving memoir that tracks Rebecca Solnit's path as a young woman in the world of predatory men, a young writer in the patriarchal literary world, and finally, a voice whose wisdom is sought by many. Instructive for those of us who think deeply about the directions of our lives.

emotional

reflective

medium-paced

Haunting, subdued. This memoir reads more as a series of thematic essays rather than a chronological memoir. The points made are powerful -- Solnit outlines some painful and indeed ignored ways in which women experience subtle and not so subtle sexism and rape culture. This wasn't really a book I wanted to pick up and return to continually, but when I did, I found the points poignant and worth discussing.

A powerful book part feminist essay and part memoir of her life mostly from the 1970s-80s in San Francisco. She describes her early years researching artists and the Nevada Test Site, native tribes, and the Beat Generation. Most moving were her reflections in the Afterword which offer hope to those who have been marginalized or made invisible.