Take a photo of a barcode or cover

challenging

emotional

hopeful

informative

reflective

sad

fast-paced

read on Scribd

I smiled and nodded and gritted my teeth and still pretended everything was fine. (9)

There is a point during a long-haul flight when you stare out the window into the inky dark of night over the vast ocean and think 'I will never escape this place. This is where I live now.' And then you look at the monitor and see that there are still ten hours left of the flight. It is only then that you can understand hopelessness of a trivial nature. (11)

In truth, I wasn’t ready. I wasn’t ready to hurt myself in the way I would have to hurt myself to detail what happened and how and what it felt like to be in my body as my body was callously taken apart. (7)

I wrote around my trauma because it was the only thing I could do. I did not yet know how to make myself be heard. (7)

When I was twelve years, [details of her trauma]. It’s not an interesting story. I am, frankly, exhausted with the story. It’s just my truth. It’s a horrifyingly common experience. (6)

In an instant, I became a stranger to everyone who knew me. I became a stranger to myself. I had no idea how to explain who I was becoming. I had no idea how to keep myself from shattering, so I did. I shattered, but my skin hid all the broken shards of who I had been. It was easy to hide in plain sight. (6)

I wanted to lose myself because I was losing my mind. I was breaking under the pressure of trying to the good daughter and the perfect student when I was so desperately far from perfect. (4)

I was worried I was being too sensitive, and maybe I was, but I was still entitled to my feelings. (12)

I began to realise that whether I wanted it or not, I had a responsibility not only to myself, but to my readers who, in response to my trusting them with so much intimacy, asked me to trust them with their own intimacies. I realised that when writing about trauma, you have to be prepared to handle not only your own trauma but being exposed to the trauma of others. (14)

I was shy and awkward and unfocused. I didn’t know what to study or what I wanted to be when I grew up. I had a rich imaginary life on the early internet, because I found the drab greyness of New Haven unbearable. I was supposed to be happy at Yale, and I was supposed to be grateful to be there, but I wasn’t. I was too broken to appreciate anything about my life. (15)

I did not want to step back into the life I had obliterated when I dropped out. There was nothing but bad memories waiting for me and an overwhelming sense of disappointment in myself. I felt like a failure. I was so fragile I couldn’t hack the place once, so why try again? I had been handed the opportunity of a lifetime, and I blew it. Or, I suppose, that’s what it looked like from the outside looking in. (15-6)

I hoped they would understanding why I was having them read these books. If I could smart to my students - to anyone who wants to write about trauma, really - one thing, it would be to make the incomprehensible comprehensible, to create a space within a narrative for both the writer and the reader to see themselves to understand something necessary about themselves. (24)

I tend to compartmentalise. My professional life exists in one compartment and my personal life in another. My compartments have compartments. (28)

It is difficult to write about personal trauma but it is also difficult to write about collective trauma, the trauma of oppression or poverty or authoritarianism or pandemic. When I write about collective trauma, I am trying to make sense of the world we’re living in, even though the world so rarely makes sense. Sometimes, in writing about collective trauma, everything seems terribly hopeless. The things we are up against, the things the most vulnerable people are up against, are immovable, intractable. Writing about them feels futile. It feels unreal. It is sometimes painful. It is sometimes numbing. (29-30)

So I look outward. I look at everything happening in the world, and think, I have to say something. And then I start to think I have nothing left to say on those subjects either. … but… How can I stay silent in the face of these calamities? How can I look away? How dare I look away? (32)

People started taking my writing as seriously as I’ve always taken it, and I wrote relentlessly and studied and read and got a job and taught and tried to make a life for myself. I tried to make myself into someone who could enjoy that life. (16)

Not all writing about trauma is created equal. As with most subjects, writers can be careless with trauma. They can be solipsistic. They can write concerns only with what they need to say and not with an audience might need to hear. They assume that their trauma, in and of itself, is inherently interesting. (16)

I have a confession. I get so tired of the word trauma. It is so clinical, so desperately inadequate. It is such a specific word, but it could mean anything. It could be the aftermath of sexual violence or domestic violence or emotional abuse of the trauma that rises out of bigotry to the trauma of fighting in or living through a war or the trauma of grief or the trauma of school shootings and other community violence. There is acute trauma, repetitive trauma, complex trauma, developmental trauma, vicarious trauma, and historical or intergenerational trauma. Trauma shapes all of our lives, in so many ways. We are walking wounds, but I am not sure any of us know how to talk about it. (17)

It made me wonder, as I do every day, how long we will live like this. It has been months, and it could be many months more, and it could be years. (32)

This is a terrible story. This is a profoundly traumatic story. Forgive me for telling this story. And still, it needs to be told. (34)

When I got my ID, I finally did feel something, but it was indescribable. (21)

The libraries were exactly where I left them. (21)

In designing the course, I had far more questions than answers. How do we write trauma? How do we convey the realities of trauma and its aftermath without being exploitative? how do we write trauma without traumatising the reader? How do we write trauma without re-traumatising ourselves when we write from personal experience? How do we write trauma without cannibalising ourselves? How do we write about the traumatic experiences of others without transgressing their boundaries or privacy? How do we tell stories of of trauma without allowing the trauma to become the whole of our narratives? What does it even mean to write trauma? These are questions I have long grappled with in my own writing. (19)

One of my primary objectives [in leading a writing workshop on trauma] was to remind students that they were, ultimately, writing for an audience, not using the work solely as a therapeutic means of processing traumatic experiences. (19)

When you’re finally ready to write about trauma, there is a temptation to offer up your testimony, to transcribe all the brutal details as if that is the whole of the work that needs to be done. There is a temptation to indulge in not so much writing but it confession. Sometimes suffering becomes more bearable when you can share the whole truth of it. (16)

To heal from a trauma, we need to understand the extent of it. (34)

People are stepping outside their comfort and complacency because they recognise the urgency of this moment. (36)

There are other ways to bear witness than subjecting yourself to the sight of cruel disregard for the humanity of Black people. There is never a day when Black people can breathe easy, let their shoulders down, close their eyes and feel safe. (37)

There is no pleasure to be had in writing about trauma. It requires opening a wound, looking into the bloody gape of it, and cleaning it out, one word at a time. Only then might it be possible for that wound to heal. (37)

I am so tired of writing about my own trauma. I am bored with it. Although I am still dealing with the repercussions, I have nothing left to say on the subject. At least that’s what I tell myself. (30)

I smiled and nodded and gritted my teeth and still pretended everything was fine. (9)

There is a point during a long-haul flight when you stare out the window into the inky dark of night over the vast ocean and think 'I will never escape this place. This is where I live now.' And then you look at the monitor and see that there are still ten hours left of the flight. It is only then that you can understand hopelessness of a trivial nature. (11)

In truth, I wasn’t ready. I wasn’t ready to hurt myself in the way I would have to hurt myself to detail what happened and how and what it felt like to be in my body as my body was callously taken apart. (7)

I wrote around my trauma because it was the only thing I could do. I did not yet know how to make myself be heard. (7)

When I was twelve years, [details of her trauma]. It’s not an interesting story. I am, frankly, exhausted with the story. It’s just my truth. It’s a horrifyingly common experience. (6)

In an instant, I became a stranger to everyone who knew me. I became a stranger to myself. I had no idea how to explain who I was becoming. I had no idea how to keep myself from shattering, so I did. I shattered, but my skin hid all the broken shards of who I had been. It was easy to hide in plain sight. (6)

I wanted to lose myself because I was losing my mind. I was breaking under the pressure of trying to the good daughter and the perfect student when I was so desperately far from perfect. (4)

I was worried I was being too sensitive, and maybe I was, but I was still entitled to my feelings. (12)

I began to realise that whether I wanted it or not, I had a responsibility not only to myself, but to my readers who, in response to my trusting them with so much intimacy, asked me to trust them with their own intimacies. I realised that when writing about trauma, you have to be prepared to handle not only your own trauma but being exposed to the trauma of others. (14)

I was shy and awkward and unfocused. I didn’t know what to study or what I wanted to be when I grew up. I had a rich imaginary life on the early internet, because I found the drab greyness of New Haven unbearable. I was supposed to be happy at Yale, and I was supposed to be grateful to be there, but I wasn’t. I was too broken to appreciate anything about my life. (15)

I did not want to step back into the life I had obliterated when I dropped out. There was nothing but bad memories waiting for me and an overwhelming sense of disappointment in myself. I felt like a failure. I was so fragile I couldn’t hack the place once, so why try again? I had been handed the opportunity of a lifetime, and I blew it. Or, I suppose, that’s what it looked like from the outside looking in. (15-6)

I hoped they would understanding why I was having them read these books. If I could smart to my students - to anyone who wants to write about trauma, really - one thing, it would be to make the incomprehensible comprehensible, to create a space within a narrative for both the writer and the reader to see themselves to understand something necessary about themselves. (24)

I tend to compartmentalise. My professional life exists in one compartment and my personal life in another. My compartments have compartments. (28)

It is difficult to write about personal trauma but it is also difficult to write about collective trauma, the trauma of oppression or poverty or authoritarianism or pandemic. When I write about collective trauma, I am trying to make sense of the world we’re living in, even though the world so rarely makes sense. Sometimes, in writing about collective trauma, everything seems terribly hopeless. The things we are up against, the things the most vulnerable people are up against, are immovable, intractable. Writing about them feels futile. It feels unreal. It is sometimes painful. It is sometimes numbing. (29-30)

So I look outward. I look at everything happening in the world, and think, I have to say something. And then I start to think I have nothing left to say on those subjects either. … but… How can I stay silent in the face of these calamities? How can I look away? How dare I look away? (32)

People started taking my writing as seriously as I’ve always taken it, and I wrote relentlessly and studied and read and got a job and taught and tried to make a life for myself. I tried to make myself into someone who could enjoy that life. (16)

Not all writing about trauma is created equal. As with most subjects, writers can be careless with trauma. They can be solipsistic. They can write concerns only with what they need to say and not with an audience might need to hear. They assume that their trauma, in and of itself, is inherently interesting. (16)

I have a confession. I get so tired of the word trauma. It is so clinical, so desperately inadequate. It is such a specific word, but it could mean anything. It could be the aftermath of sexual violence or domestic violence or emotional abuse of the trauma that rises out of bigotry to the trauma of fighting in or living through a war or the trauma of grief or the trauma of school shootings and other community violence. There is acute trauma, repetitive trauma, complex trauma, developmental trauma, vicarious trauma, and historical or intergenerational trauma. Trauma shapes all of our lives, in so many ways. We are walking wounds, but I am not sure any of us know how to talk about it. (17)

It made me wonder, as I do every day, how long we will live like this. It has been months, and it could be many months more, and it could be years. (32)

This is a terrible story. This is a profoundly traumatic story. Forgive me for telling this story. And still, it needs to be told. (34)

When I got my ID, I finally did feel something, but it was indescribable. (21)

The libraries were exactly where I left them. (21)

In designing the course, I had far more questions than answers. How do we write trauma? How do we convey the realities of trauma and its aftermath without being exploitative? how do we write trauma without traumatising the reader? How do we write trauma without re-traumatising ourselves when we write from personal experience? How do we write trauma without cannibalising ourselves? How do we write about the traumatic experiences of others without transgressing their boundaries or privacy? How do we tell stories of of trauma without allowing the trauma to become the whole of our narratives? What does it even mean to write trauma? These are questions I have long grappled with in my own writing. (19)

One of my primary objectives [in leading a writing workshop on trauma] was to remind students that they were, ultimately, writing for an audience, not using the work solely as a therapeutic means of processing traumatic experiences. (19)

When you’re finally ready to write about trauma, there is a temptation to offer up your testimony, to transcribe all the brutal details as if that is the whole of the work that needs to be done. There is a temptation to indulge in not so much writing but it confession. Sometimes suffering becomes more bearable when you can share the whole truth of it. (16)

To heal from a trauma, we need to understand the extent of it. (34)

People are stepping outside their comfort and complacency because they recognise the urgency of this moment. (36)

There are other ways to bear witness than subjecting yourself to the sight of cruel disregard for the humanity of Black people. There is never a day when Black people can breathe easy, let their shoulders down, close their eyes and feel safe. (37)

There is no pleasure to be had in writing about trauma. It requires opening a wound, looking into the bloody gape of it, and cleaning it out, one word at a time. Only then might it be possible for that wound to heal. (37)

I am so tired of writing about my own trauma. I am bored with it. Although I am still dealing with the repercussions, I have nothing left to say on the subject. At least that’s what I tell myself. (30)

challenging

dark

emotional

fast-paced

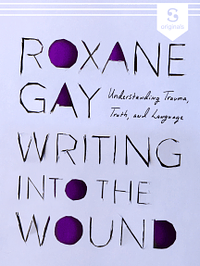

Wow- Gay never disappoints in exposing unvarnished, universal, and, at times, brutal truisms.

This novella could be viewed as a follow up to Gay’s ‘Hunger.’ She discuses her quixotic & sometimes trauma-compounding book tour for ‘Hunger’ and class teaching on the writing of trauma at Yale.

Gay elaborates on her role as an author writing about her trauma and to make such trauma fit within the greater “collective trauma” of the world.

Gay ties this “collective trauma” to today’s pandemic and the gross inequalities COVID-19 exposed both in our healthcare system and in the ways in which the 99% live their daily lives. Oh- and she holds no punches against President 45. She’s not hyperbolic or disingenuous- Gay gives readers the truth.

This novella could be viewed as a follow up to Gay’s ‘Hunger.’ She discuses her quixotic & sometimes trauma-compounding book tour for ‘Hunger’ and class teaching on the writing of trauma at Yale.

Gay elaborates on her role as an author writing about her trauma and to make such trauma fit within the greater “collective trauma” of the world.

Gay ties this “collective trauma” to today’s pandemic and the gross inequalities COVID-19 exposed both in our healthcare system and in the ways in which the 99% live their daily lives. Oh- and she holds no punches against President 45. She’s not hyperbolic or disingenuous- Gay gives readers the truth.

informative

inspiring

fast-paced

informative

reflective

I’ve wanted to read Hunger by this author for a while, but I’ve honestly been scared. Reading this book helped me to understand her perspective on writing about trauma and what her experience has been like telling her story.

reflective

fast-paced

informative

reflective

fast-paced

reflective

fast-paced

i love the name of this book and, even after i’m done reading it, the words feels like a punch in the gut. an emergency call begging me to confront the brutal reality most of us life in. i thought it at time a little too detailed. but otherwise this is so heartbreakingly beautiful