Scan barcode

gh7's review against another edition

5.0

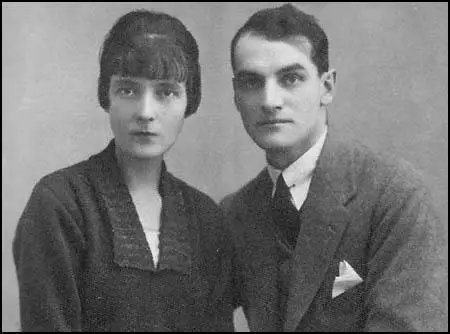

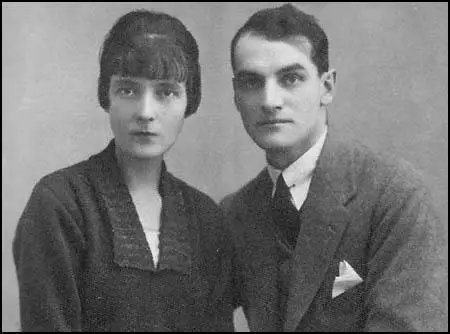

What sparked my lifelong fascination with Katherine Mansfield was not so much her stories – I preferred Woolf as a writer – but her letters and journal. I was bewitched by Mansfield the woman. Deeply moved by the tragedy of her short life. I also fell in love with her relationship with John Middleton Murry – which, in those days, had been edited down (by Murry himself) to essentially a beautiful tragic high tide romance of kindred souls.

As a person Katherine was much more fascinating to me than Woolf. She seemed at least three generations ahead of Virginia. I could easily imagine Katherine in our contemporary world; especially her headstrong pioneering nature, her stage-managed narcissism, her refusal to bow down to convention, her need to give expression to multiple facets of her personality; Woolf, on the other hand, was far more Victorian in her corseted diffidence, caution and class snobbery. All mouth and no trousers, you might say!

I had an insatiable need to know everything about Mansfield. I read the excellent biography by Anthony Alpers, though this was hampered by being written while Murry, who jealously censored and guarded Mansfield’s papers, was still alive. That said, I felt Alpers shared my own love and fascination for her and the tone, the emotional fabric of his book was marvellously in tune with what I wanted. Claire Tomlin’s later biography on the other hand, boasting new information, was a dispassionate affair that failed for me to convey any of Katherine’s magical allure.

In those days I trawled the Charing Cross Road second hand book stores looking for anything about her. One of the most exciting days was finding a copy of the letters between Mansfield and Middleton Murry. Suddenly I had the other side of the story. And however much Murry edited these letters to show himself in a good light they are genuinely beautiful and heartbreaking. I then read everything I could find about Middleton Murry – including some truly horrible poems, a woefully inept novel (how could someone so intelligent who spent all his time engrossed in literature write a novel so comically bad?) and an equally forgettable collection of essays. I came to think of them as the English/colonial version of Scott and Zelda, another of my teenage fascinations.

The author here makes a few curious artistic choices. Firstly, as was the case with The BBC dramatization of KM’s life she begins with Katherine’s death. Secondly she writes part of the narrative in the present tense with a perspective that is perhaps closer to a novelist than a biographer. Thirdly her punctuation is a bit eccentric at times. And fourthly she twice interrupts the chronology to insert accounts of Murry’s married life after Katherine’s death. Though this fascinated me I’m not sure Murry had been sufficiently developed at this point to make it fascinating for anyone who knew little about KM’s life. It’s worth noting that Murry became the most hated man in literary England. His exploitation of Katherine’s work for economic gain and subsequent maudlin pseudo-mystical justifications and his self-serving determination to recast her as a kind of deity of purity attracted hostility and scorn from all and sundry. However, I soon grew used to the present tense and though I’m not convinced anything was gained by using it and it just seemed eccentric it stopped bothering me.

First thing, had I read this biography at nineteen, and not the kinder one by Anthony Alpers, I probably would have objected to its more critical approach. I had my illusions and didn’t want them shattered. Kathleen Jones gravitates towards documenting the failings, rather than the achievements, of both KM and JMM in this biography; Alpers was perhaps more alert to the triumphs, both in her writing and in her relationships. Murry especially does not come out of this well. In fact you’re left wondering what the hell she saw in him. History has debunked him in all his literary aspiration; here, he’s almost conclusively tarnished as a husband (and, later, as a father). An example, Katherine is still weak and demoralised after having had an infected gland punctured in a surgical intervention. In the taxi on the way home Murry insists she pays half the fare and the tip. Later, she writes to a friend, “Fancy not paying your wife’s carriage to and from surgery. I suppose if one fainted he would make one pay 3d for a 6d glass of sal volatile.” You can’t help wondering what Murry felt after she died and he had to read this kind of thing about himself while editing her letters. My romantic notion of their relationship had by now gone for a Burton!

That said, little space was given in this biography to their compatibility as romantic playmates – I remember being utterly mesmerised by the way Katherine animated her doll Ribni as a kind of playful cypher for her feelings of love and mischief when they were apart and writing to each other and how well Murry entered into the spirit of the game. In Murry’s defence there’s a sense Katherine had already written the script of the relationship she wanted and tried, successfully at times, to cajole Murry to play the leading role. Both she and Murry come across as people who love being in love in imagination. In other words, they’re both much better at expressing romantic feeling when they are alone. Probably this changed when she was very ill and needed a more practical form of support. This is when Murry is completely out of his depth. It’s when she’s dying that he becomes a monster of ineptitude. There’s also a sense that Katherine is stage-managing how she wants to be seen in both her letters and journal. Her observations on writing and the physical world are brilliant; her commentaries on people, rarely generous, sometimes whiff of self-serving duplicity. She puts people down to elevate herself. Perhaps she’s editing her own letters no less than Murry did after her death. Again to give the author of this biography credit, she probably just about gave Murry the benefit of the doubt. At the end of the day if you write off Murry you also have to reduce much of Katherine’s life to waste which is neither fair nor true. And, in his defence, he took her back after she swanned off to France to have an affair with a friend of his.

This biography definitely opened up a new perspective on KM for me. One thing that occurred to me and began puzzling me was how KM seemed to bring out the worst in people. Did this point to some central falsity in her own nature? (Late in her life she said about herself, You can't drink clean water out of a dirty glass.) Though she enriched a few of the lives around her you can’t really say she did it intentionally or with the best will. Ida Baker, lifelong companion, loved her unconditionally despite Katherine constantly mocking her and perhaps would have lived a more fulfilled life without her. (Alpers was cruel about Ida, seeing her as little more than a lovesick slavish servant. Katherine too was often cruel about her. An intellectual snobbery often creeps into her voice whenever she talks about Ida. But Ida always dropped everything to assist Katherine and ultimately was probably a better soulmate to KM than Murry. I liked the author for giving a more sympathetic portrait of the virginal vampiric Ida.) Murry was ultimately consumed and dwarfed by her. His only claim to literary fame now is the fact of being her husband. Another of her former lovers ended up blackmailing her, hardly an act he would have looked back on with any pride. An anecdote often used to display how nasty Lawrence could be is his famous letter to Katherine telling her he hopes she will stew in her consumption. Wyndham Lewis publicly dismissed her as vulgar, dull and unpleasant to mutual friends (ha ha, that posterity reveres her achievement much higher than yours, mate!) And then there’s the diabolically two-faced Virginia Woolf. At this point, KM was ahead of Virginia. There’s a freshness and innovation of technique in The Garden Party and At the Bay that is beyond anything Woolf has managed in The Voyage Out and especially her somewhat laboured second novel, Night and Day. Every time Woolf mentions Mansfield, except after she’s dead, she comes across as a jealous, spiteful, frumpy snob. Yet she does nothing but praise her in letters written to Katherine. Again Katherine has managed to bring out the worst in someone. (This is my idea, rather than the author’s by the way.)

(A note on literary prizes. Bliss was awarded third prize behind a novel none of us has ever heard of now. Good to see the highly dubious integrity of prizes has been consistent through the decades. I can think of at least three Booker winners that I doubt if anyone will have heard of in 100 years and a number of non-winners that will still be admired.)

Another thing I pondered while reading this: Do we have an inkling of our fate and are therefore attracted to stories and people who we sense mirror it in some way or do our early imaginative identifications create that fate? It’s fascinating that at a very young age Katherine was immensely attracted to the journal of a young Russian writer, Marie Bashkirtseff who was dying of consumption. A decade later Katherine’s own journal would take on an eerily similar tone.

Essentially Kathleen Jones’ biography does a grand job of bringing Katherine back to life and anyone who does that gets five stars from me. It put me through the heartbreak of the last year of her life again and I didn’t want it to end. Probably most writers write too many books. Mansfield didn’t write enough. If there’s one book I could read that never got written it would be Katherine’s follow up to The Garden Party. I’ve always been super proud of sharing a birthday with Katherine Mansfield.

As a person Katherine was much more fascinating to me than Woolf. She seemed at least three generations ahead of Virginia. I could easily imagine Katherine in our contemporary world; especially her headstrong pioneering nature, her stage-managed narcissism, her refusal to bow down to convention, her need to give expression to multiple facets of her personality; Woolf, on the other hand, was far more Victorian in her corseted diffidence, caution and class snobbery. All mouth and no trousers, you might say!

I had an insatiable need to know everything about Mansfield. I read the excellent biography by Anthony Alpers, though this was hampered by being written while Murry, who jealously censored and guarded Mansfield’s papers, was still alive. That said, I felt Alpers shared my own love and fascination for her and the tone, the emotional fabric of his book was marvellously in tune with what I wanted. Claire Tomlin’s later biography on the other hand, boasting new information, was a dispassionate affair that failed for me to convey any of Katherine’s magical allure.

In those days I trawled the Charing Cross Road second hand book stores looking for anything about her. One of the most exciting days was finding a copy of the letters between Mansfield and Middleton Murry. Suddenly I had the other side of the story. And however much Murry edited these letters to show himself in a good light they are genuinely beautiful and heartbreaking. I then read everything I could find about Middleton Murry – including some truly horrible poems, a woefully inept novel (how could someone so intelligent who spent all his time engrossed in literature write a novel so comically bad?) and an equally forgettable collection of essays. I came to think of them as the English/colonial version of Scott and Zelda, another of my teenage fascinations.

The author here makes a few curious artistic choices. Firstly, as was the case with The BBC dramatization of KM’s life she begins with Katherine’s death. Secondly she writes part of the narrative in the present tense with a perspective that is perhaps closer to a novelist than a biographer. Thirdly her punctuation is a bit eccentric at times. And fourthly she twice interrupts the chronology to insert accounts of Murry’s married life after Katherine’s death. Though this fascinated me I’m not sure Murry had been sufficiently developed at this point to make it fascinating for anyone who knew little about KM’s life. It’s worth noting that Murry became the most hated man in literary England. His exploitation of Katherine’s work for economic gain and subsequent maudlin pseudo-mystical justifications and his self-serving determination to recast her as a kind of deity of purity attracted hostility and scorn from all and sundry. However, I soon grew used to the present tense and though I’m not convinced anything was gained by using it and it just seemed eccentric it stopped bothering me.

First thing, had I read this biography at nineteen, and not the kinder one by Anthony Alpers, I probably would have objected to its more critical approach. I had my illusions and didn’t want them shattered. Kathleen Jones gravitates towards documenting the failings, rather than the achievements, of both KM and JMM in this biography; Alpers was perhaps more alert to the triumphs, both in her writing and in her relationships. Murry especially does not come out of this well. In fact you’re left wondering what the hell she saw in him. History has debunked him in all his literary aspiration; here, he’s almost conclusively tarnished as a husband (and, later, as a father). An example, Katherine is still weak and demoralised after having had an infected gland punctured in a surgical intervention. In the taxi on the way home Murry insists she pays half the fare and the tip. Later, she writes to a friend, “Fancy not paying your wife’s carriage to and from surgery. I suppose if one fainted he would make one pay 3d for a 6d glass of sal volatile.” You can’t help wondering what Murry felt after she died and he had to read this kind of thing about himself while editing her letters. My romantic notion of their relationship had by now gone for a Burton!

That said, little space was given in this biography to their compatibility as romantic playmates – I remember being utterly mesmerised by the way Katherine animated her doll Ribni as a kind of playful cypher for her feelings of love and mischief when they were apart and writing to each other and how well Murry entered into the spirit of the game. In Murry’s defence there’s a sense Katherine had already written the script of the relationship she wanted and tried, successfully at times, to cajole Murry to play the leading role. Both she and Murry come across as people who love being in love in imagination. In other words, they’re both much better at expressing romantic feeling when they are alone. Probably this changed when she was very ill and needed a more practical form of support. This is when Murry is completely out of his depth. It’s when she’s dying that he becomes a monster of ineptitude. There’s also a sense that Katherine is stage-managing how she wants to be seen in both her letters and journal. Her observations on writing and the physical world are brilliant; her commentaries on people, rarely generous, sometimes whiff of self-serving duplicity. She puts people down to elevate herself. Perhaps she’s editing her own letters no less than Murry did after her death. Again to give the author of this biography credit, she probably just about gave Murry the benefit of the doubt. At the end of the day if you write off Murry you also have to reduce much of Katherine’s life to waste which is neither fair nor true. And, in his defence, he took her back after she swanned off to France to have an affair with a friend of his.

This biography definitely opened up a new perspective on KM for me. One thing that occurred to me and began puzzling me was how KM seemed to bring out the worst in people. Did this point to some central falsity in her own nature? (Late in her life she said about herself, You can't drink clean water out of a dirty glass.) Though she enriched a few of the lives around her you can’t really say she did it intentionally or with the best will. Ida Baker, lifelong companion, loved her unconditionally despite Katherine constantly mocking her and perhaps would have lived a more fulfilled life without her. (Alpers was cruel about Ida, seeing her as little more than a lovesick slavish servant. Katherine too was often cruel about her. An intellectual snobbery often creeps into her voice whenever she talks about Ida. But Ida always dropped everything to assist Katherine and ultimately was probably a better soulmate to KM than Murry. I liked the author for giving a more sympathetic portrait of the virginal vampiric Ida.) Murry was ultimately consumed and dwarfed by her. His only claim to literary fame now is the fact of being her husband. Another of her former lovers ended up blackmailing her, hardly an act he would have looked back on with any pride. An anecdote often used to display how nasty Lawrence could be is his famous letter to Katherine telling her he hopes she will stew in her consumption. Wyndham Lewis publicly dismissed her as vulgar, dull and unpleasant to mutual friends (ha ha, that posterity reveres her achievement much higher than yours, mate!) And then there’s the diabolically two-faced Virginia Woolf. At this point, KM was ahead of Virginia. There’s a freshness and innovation of technique in The Garden Party and At the Bay that is beyond anything Woolf has managed in The Voyage Out and especially her somewhat laboured second novel, Night and Day. Every time Woolf mentions Mansfield, except after she’s dead, she comes across as a jealous, spiteful, frumpy snob. Yet she does nothing but praise her in letters written to Katherine. Again Katherine has managed to bring out the worst in someone. (This is my idea, rather than the author’s by the way.)

(A note on literary prizes. Bliss was awarded third prize behind a novel none of us has ever heard of now. Good to see the highly dubious integrity of prizes has been consistent through the decades. I can think of at least three Booker winners that I doubt if anyone will have heard of in 100 years and a number of non-winners that will still be admired.)

Another thing I pondered while reading this: Do we have an inkling of our fate and are therefore attracted to stories and people who we sense mirror it in some way or do our early imaginative identifications create that fate? It’s fascinating that at a very young age Katherine was immensely attracted to the journal of a young Russian writer, Marie Bashkirtseff who was dying of consumption. A decade later Katherine’s own journal would take on an eerily similar tone.

Essentially Kathleen Jones’ biography does a grand job of bringing Katherine back to life and anyone who does that gets five stars from me. It put me through the heartbreak of the last year of her life again and I didn’t want it to end. Probably most writers write too many books. Mansfield didn’t write enough. If there’s one book I could read that never got written it would be Katherine’s follow up to The Garden Party. I’ve always been super proud of sharing a birthday with Katherine Mansfield.

More...